Born Trevor Smith (he changed his name by deed-poll, referencing a character in one of his hero Marc Bolan’s songs), Jason’s first notable band went under the name Disraeli Gears (after the Cream album). Based in Whanganui, Disraeli Gears also featured Andrew Johns, Anthony Johns and David Mauger, but proved short lived.

Jason moved to Palmerston North to attend Massey University and dabble in a progression of student bands while the Johns Brothers and Mauger relocated to Auckland with fellow Whanganui fledglings Craig Smith-Pilling and (later assistant to Bono of U2) Greg Carroll to form, and record as, Blond Comedy – and then (most of them) do it all again as National Anthem.

Whanganui musician David Rogerson knew and worked with Jason, first in the late 70s and then again in Jason’s final decade. Rogerson recalls, “He took guitar lessons from the late John Bilderbeck and was a formidable player in his own way, knew his fretboard, understood chord chemistry and was an astonishing, jazzy, rhythm player. He’d spring a completely new song on me at practice, fire off a string of three-note chords and say ‘It goes like this’. As we seldom had a bass player, it took me a little while to click that he never played the root note of the chord (I think he could hear the bassline in his head). Sometimes he lost me completely, and when I asked him about a chord or chords, he’d say ‘You don't need to know the chords; I’m playing the chords. What I want from you is a motif.’”

jason headed to the homeland of his hero Marc Bolan, with two Gibson guitars in his luggage.

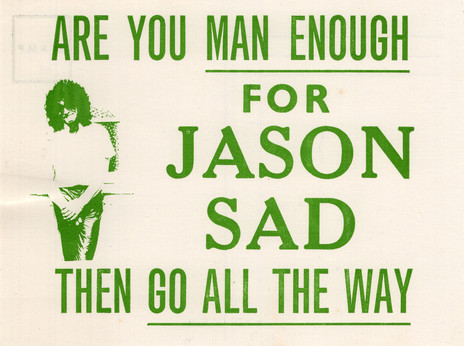

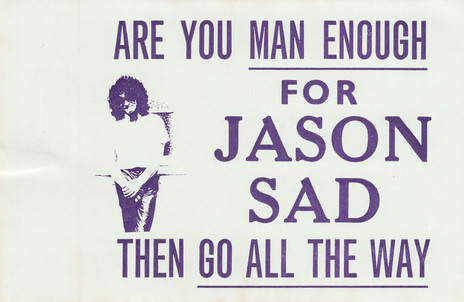

Following his brief stint at Massey, and feeling he’d achieved all he could there (academia not necessarily being a consideration), Sad headed to the homeland of his hero Marc Bolan. In his luggage were his two Gibson guitars, one of which, he told me, he eventually sold to pay for his return ticket. “I was over in London [and] I used to get badges made up and sell them at Jam concerts … it was the do-it-yourself era …” On his return to New Zealand, Sad brought this DIY approach along with him. “[It was] an effort to circumvent the big labels, who were not too helpful in those days.” He also brought a taste for glam rock and his memories of the pop marketing methods he’d seen used to such good effect in London.

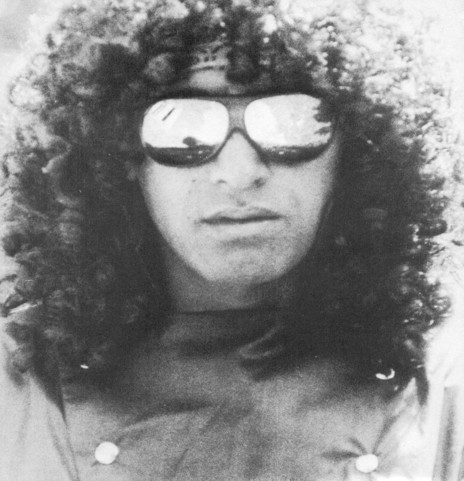

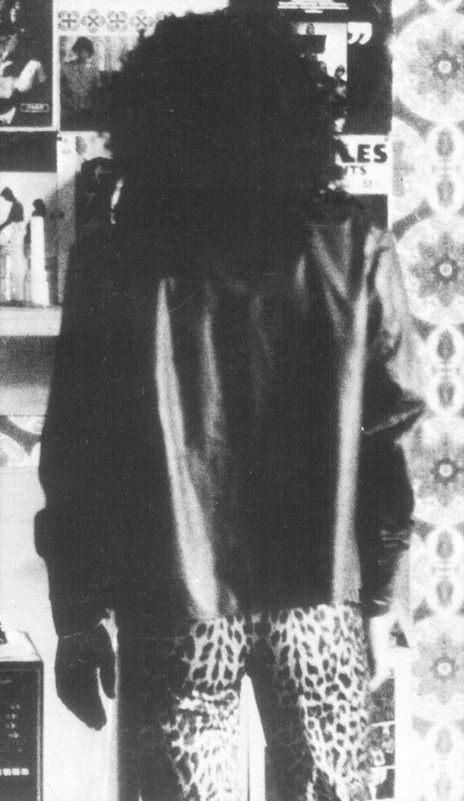

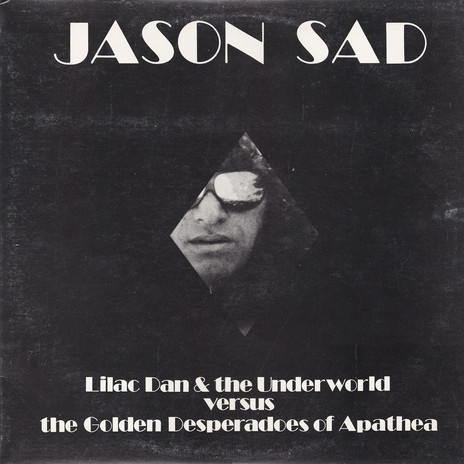

The timeline around Jason’s early releases and his time in England is blurred. Jason’s accounts when interviewed were vague and, not surprisingly given his tendency to hype, a substantial part of the information he imparted has proven to be either unsubstantiated or refuted by other parties. It’s safe, though, to accept Jason’s claim that the photos used on the cover of Lilac Dan … were taken in England shortly before his return to New Zealand.

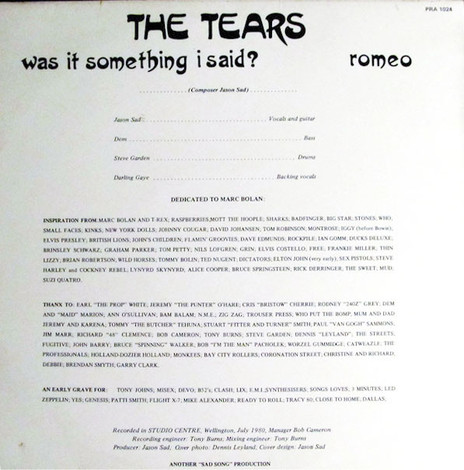

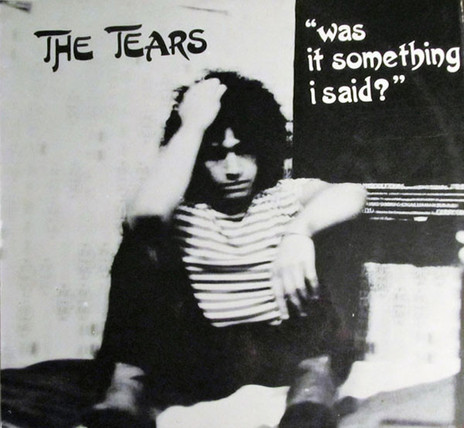

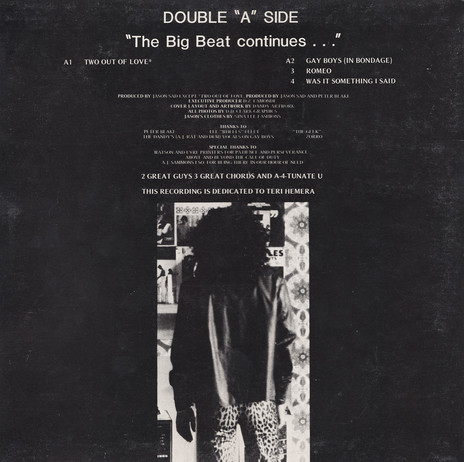

Probably while still based in Palmerston North, Jason released a 7-inch single ‘Was It Something I Said’ b/w ‘Romeo’ under the name Jason Sad, and a 12-inch version of the same recordings under the name The Tears. These songs were later re-released, along with two new tracks, on the Lilac Dan … EP. The A-side and feature track was the epic ‘Two Out Of Love’. The B-side featured the two tracks from the previous single as well as a cover of the English punk/R&B crossover act The Drug Addicts’ ‘Gay Boys (In Bondage)’.

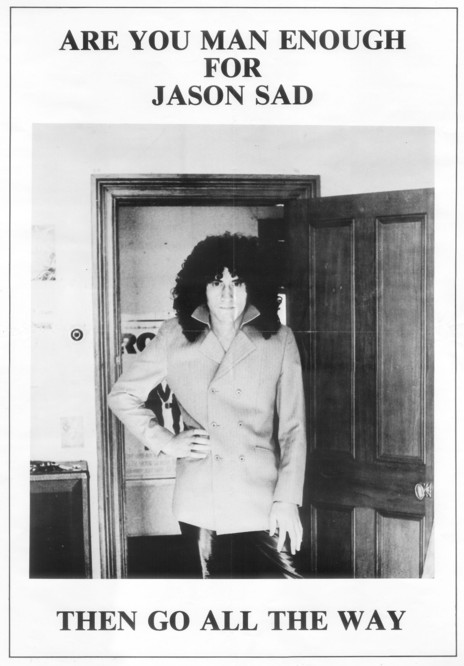

The inside artwork of Jason’s EP hit complete overkill, with stickers, postcards and a poster portrait.

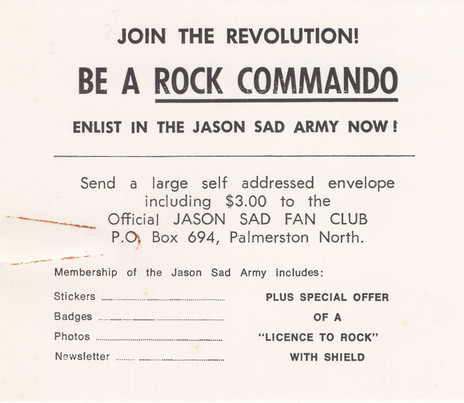

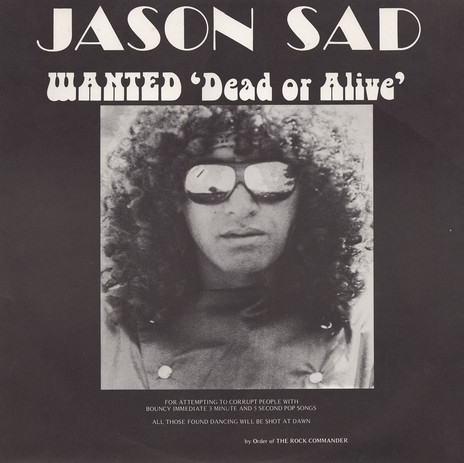

On the front cover of the EP, Sad’s face appears framed in a diamond; on the other side is a view of his back with glam-rock hair, leather jacket and leopard-skin trousers. The inside artwork hits complete overkill with a close-up photo of Jason on the inner sleeve plus stickers, postcards and a two-foot tall poster featuring Jason posed in front of a doorway. If this wasn’t already enough there was also a “Jason Sad Rock Commando” membership card (inviting the eager fan to send $3 to a PO Box in Palmerston North and promising more stickers, badges, photos, a newsletter, and ‘A “LICENSE TO ROCK” WITH SHIELD’). The cover bears the full title Lilac Dan & the Underworld versus the Golden Desperadoes of Apathea but the record label holds the much simpler title of Saduction. The inner sleeve proclaims “JASON SAD WANTED ‘Dead or Alive’ FOR ATTEMPTING TO CORRUPT PEOPLE WITH BOUNCY IMMEDIATE 3 MINUTE AND 5 SECOND POP SONGS – ALL THOSE FOUND DANCING WILL BE SHOT AT DAWN by Order of THE ROCK COMMANDER”.

Decades after its release, during a break in one of Jason’s sessions, I played the EP in the studio. After it played for a couple of minutes Jason said “This is quite good. Who is it?” He’d completely forgotten his own music.

Jason may have found it forgettable but the EP was well received on release and subsequently, given its limited run, grew to cult status. If its plethora of inserts are intact, it is one of the ‘hard to finds’ of New Zealand vinyl. For Jason though, there was no great or immediate change in circumstances or in the inherent need to hustle.

Through this period he used various band names, including The Streets, Jason Sad & The Tears (or just The Tears), The Believers, The Movers, and The Fugitives. As Jason told it, bassist Dem Ngakuru (aka Zoro AKA D. Z. Lamonde) was a constant fixture, but drummers tended to come and go. Jason purchased a bus and with his band began travelling the country playing at any venue that would take them, and sleeping in the bus parked in the street.

Through the 80s he continued to record whenever he could get studio time, but it seems that these recordings, if ever completed, are now lost.

The 90s found Jason running a chain of pinball machines in Auckland, during which time his musical output was minimal. In an interview, he put this down to “the pressures of being in business”. He clearly didn’t want to be questioned further about this period of his life but was expansive with his recollections of his earlier years. He did claim to have recorded with several notable New Zealand musicians but almost certainly, perhaps inevitably, the stories he told were coloured by the history Jason himself wanted to create.

A small collection of recordings from this period, self-released on cassette (and left unmentioned/forgotten during our interview), does survive. Entitled Pump Mother#####r Pump Vol 1 and credited to The Movers (there is no indication that there was ever a “Vol 2”), the cover features a picture of Jason with a Les Paul and a small combo amp. The tracks were entitled ‘Road To Morocco’, ‘Win With Win’, ‘Bad News Brown’ and ‘Still Here Waiting’.

Our 2006 meeting and interview marked the beginning of my personal involvement with Jason, which included playing sets alongside his band Two Rivers at gigs Jason had organised, and engineering multiple studio sessions on his behalf at Whanganui’s Sasquatch Studio. The latter were chaotic substance-fuelled mayhem. Jason saw this chaos as a necessary part of the creative process. He believed that this was the way his 1970s musical heroes had made their records and therefore this was the way recording had to be done. He seemed more interested in acting out the role of a rock star in the studio than in the achieved result.

Jason saw chaos as a necessary part of the creative process.

At the end of these sessions, after hundreds of hours, I had only scraps of music to try to piece together. The parts that were great were really great. The problem was, nothing was complete. A few tracks were salvaged and mixed to a state of listenability. These were culled from a disjointed shambling with hints of genius, meandering into their beginnings out of loose jamming and bumbling out again. There were no defined starts and stops. Neither was there any comprehension of studio technique, and recommended microphone placement was seldom achievable. Jason was not easy to work with and these were not easy tracks to record or mix – even to demo standard. Jason and I butted heads numerous times through the mutual frustration brought about by our very different work ethics.

Despite his idiosyncracies in the studio Jason was a good guitarist, a very good and creative guitarist who put some grunt into his playing (listen to the one-take off-the-cuff lead guitars on ‘How Far We’ve Yet To Go’). But he could only lead: he couldn’t follow. If Jason decided to add a bar or slip to a different time signature for a bar or two, everyone had to follow him – and it was completely spontaneous – so if he did something once, you could guarantee he wouldn’t repeat it the next time around. He was forever in search of that spark of new inspiration.

At this point the thematic input to Jason’s writing had changed from his earlier topics of idealised romance and repressed homosexual desire. He was now more concerned with his family (his brother Jeremy – aka “Vinnie” – was a constant fixture on drums) and iwi connections, identifying with Whanganui’s Putiki iwi and their relationship with the Whanganui river. He also bore a grudge over the loss of family land taken under the public works act for the construction of the former Whanganui motorway bridge (now de-rated from motorway status and just considered part of State Highway 3). Jason equated this event with historic treaty injustices and actively protested for the return of his family’s land.

More than once Jason took this obsession a little too far. I vividly recall him, in a moment of stress, referring to one lovely woman who had bent over backwards to help him as “The daughter of Captain Cook”. It all seems a bit laughable now but at the time it was extremely unpleasant to witness. Jason’s tendency to interpret any difference of opinion as racism was evident in the studio as well, and didn’t improve the outcome of the sessions.

Despite the mayhem he surrounded himself with, Jason was a great organiser and a persuasive promoter. He had the ability to take an idea from germination to a fully-fledged event with apparent ease. He was a great believer in the local music scene, arranging gigs in various city establishments and inviting other acts to join in and share not just the limelight but also the coin. He had the gift of the gab, and scrubbed up in a suit and tie, could be the most convincing persuader, obtaining sponsors and significant community buy-in for a number of the events he arranged.

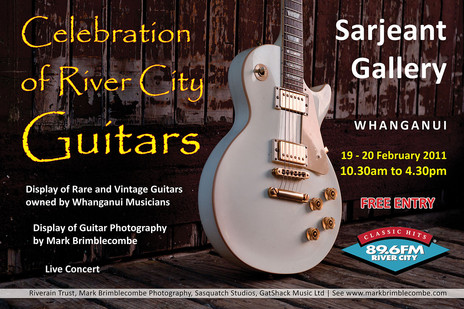

His Friends Of The Ahu charity event, organised in collaboration with fellow Whanganui character at large Fred Fredericks, in aid of the ailing Whanganui River Commune, was a significant success. Following on from this, in February 2011 Jason collaborated with art photographer Mark Brimblecombe and a committee of local guitar enthusiasts to spearhead the hugely successful Celebration of River City Guitars. Over 1200 people attended over the weekend-long event, which spawned simultaneous musical performances at multiple city venues throughout the two-day extravaganza. It also generated the largest visitor traffic ever recorded for the Whanganui City Art Gallery.

Jason then went on to shoot himself in the foot. A second event was organised on the anniversary of the first, but as it got closer Jason’s collaborators were indicating they would not be doing another. One loyal friend collaborated with Jason for a 2013 event at Palmerston North’s Te Manawa museum, however the show was closed prematurely by the museum under a cloud of controversy.

Jason died suddenly on Tuesday 21st April 2015 leaving to posterity a small but remarkable collection of recordings.

For Jason, a Friend said, “It was all about the music.”

One of the people I interviewed for this article said “Jason drank phenomenal amounts of Stella Artois and smoked more ganja than was sane or reasonable. And sometimes he could get very weird on it. Yet he was intelligent, well spoken and could be very charming and persuasive.” That statement just scratches the surface of the enigma which was Jason Sad.

At his funeral one of his friends was heard to say, “I know he had his faults, but it was all about the music with him.” It would be nice to think that those last eight words might be Jason’s epitaph: “It was all about the music with him.”