AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

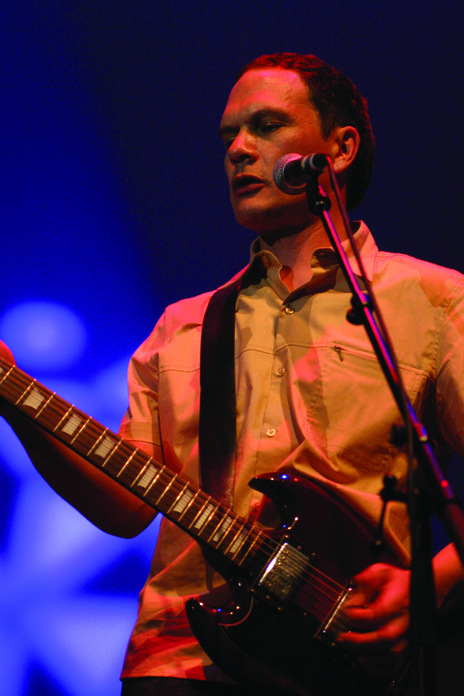

Dimmer

During this time, he started venturing into electronic music under the new name of Dimmer, which puzzled a fair few people, before heading to Auckland and making four intensely, and often quietly, beautiful records. As it turns out, that’s only half the story.

In January 1994, Straitjacket Fits played their last show at Auckland’s inaugural Big Day Out, by all accounts upstaging headliners Smashing Pumpkins and Soundgarden. Soon after this final show, Shayne Carter returned to Dunedin, completely disillusioned with the music industry and rock music in general, wanting to do something different under his own steam. “I came back here, I’d done a lot of travelling, and I guess I just basically wanted to come back home and regroup, really,” he says.

Learning to love music again, Carter looked to electronic music as a new and different direction. He spent significant time investigating early Kraftwerk and Brian Eno records, as well as European electronic bands Oval and Autechre. “To me that is great spooky shit,” he told Rip It Up in March 1997, “and it’s got a lot of qualities I’ve always loved in rock music. It’s got mystery, it’s got intrigue, and it’s got menace, but it’s coming from a completely different angle.”

It was a darker vibe that Carter was searching for, and he explained the name Dimmer to New Zealand Musician in 2001 as “I kinda wanted a spooky, claustrophobic vibe to it, that’s the whole Dimmer ethos … I wanted it shadowy and noir, I just wanted to be a bit creepy.”

Noir was a fitting descriptor for his new music.

Noir was a fitting descriptor for his new music, with the sonic landscapes mining a different, darker sound to that of his previous work. “I started developing this idea of completely minimalist, hypnotic music,” he says. “A lot of that stuff was like a primal essence of human pulse, it’s breathing, it’s sex, it’s walking … I try to bring that to the music.”

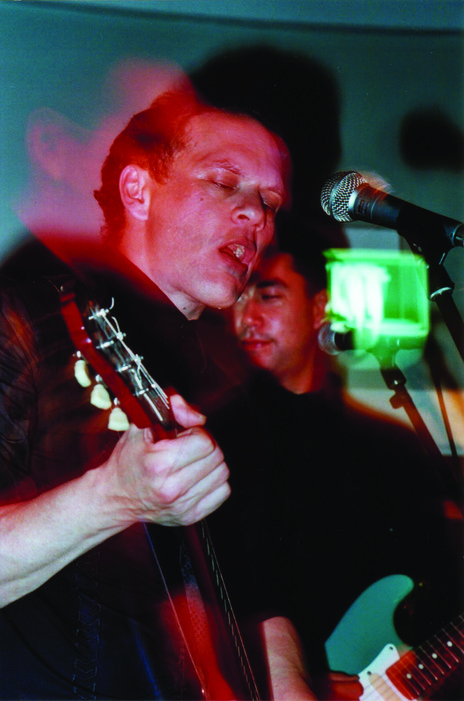

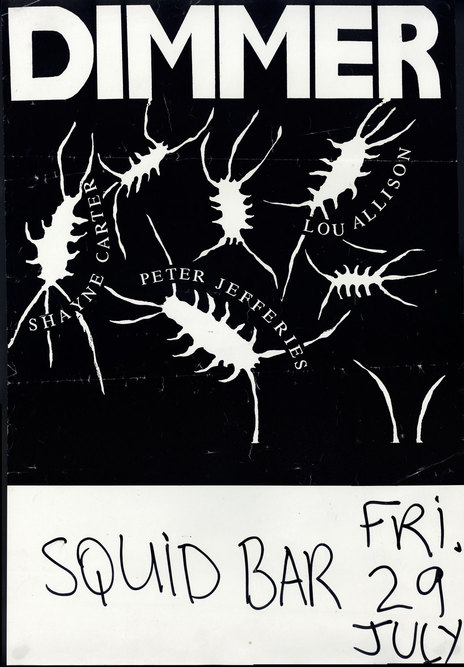

While Dimmer was a solo project revolving around Carter, he used a fluid line-up of musicians best suited to the style of music he was making. The first instance of this (with Peter Jefferies and Lou Allison) was the ‘Crystalator’ single: three incendiary minutes of guitar effects. Its B-side ‘Dawn’s Coming In’ was quieter, creeping, insistent, built around a wiry guitar line, and scattershot rhythm. The single was released on Sub Pop records in 1995. Dimmer’s first live performances were in 1996, with a short national tour.

Around this time Carter tried to record an album in Dunedin. “[It was] as early as 1995 when I tried to do the first Dimmer album, and I think around the same time, we did the ‘Crystalator’ single” with a new line-up that included Chris Heazlewood, Cameron Bain and Robbie Yeats. That album didn’t eventuate, due to the sessions ending, as Carter told Pavement magazine in 1997, in “tears, soap operas, that kinda stuff.”

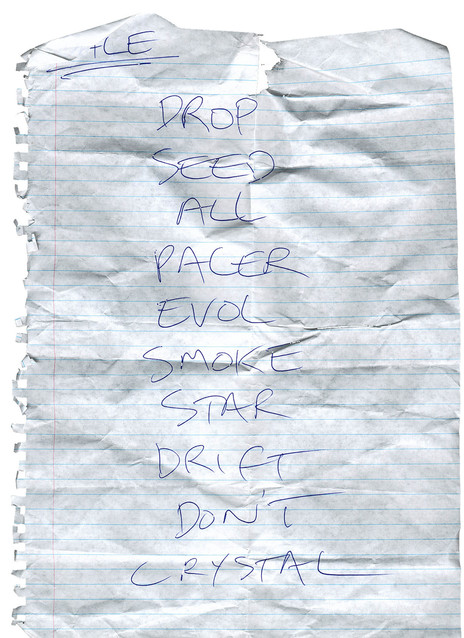

However, some material on I Believe You Are A Star, including ‘Seed’, originated from these sessions (an early version of ‘Seed’ appeared on a 1995 Australian-only cassette Star Trackers), as did ‘Don’t Make Me Buy Out Your Silence’, the title track of the Dimmer EP release (1997).

Don’t Make Me Buy Out Your Silence was a step further in the Dimmer electronica-heavy, noir pop direction: the title track was shady, and menacing in tone, with a Goodfellas style video to match. One of the B-sides was another combustible guitar instrumental, ‘Pacer’, while a third was a fuzzy cover of Canned Heat’s ‘On the Road Again’, a song Carter liked because of the way it didn’t deviate, and stayed in the same groove. In between these tracks was a small piece titled ‘Intermission’ added to the end of ‘Pacer’, a short and beautiful instrumental of chiming electronica.

By the time the EP was released, Carter had moved back to Auckland (where the recording sessions for ‘On the Road Again’ occurred). “I woke up in Dunedin in the middle of my second winter, and I was living above somewhere out by the wharf, and it was so fuckin’ freezing, I thought ‘I don’t actually have to do this’,” he laughs.

His discovery of Pro Tools via Dale Cotton around the same time only added to the new musical direction. “I had been trying to get bad versions of what I envisaged, and I was so sick of trying to explain it … because I’d been fascinated by electronic music, I thought maybe this is the way to approach it.” The first song they worked on with Pro Tools was ‘Seed’, adding drum loops and repeating them for the entire song. “I thought “that’s all I need… put on the bass, put on the guitar, did the vocal, there was the tune.”

‘Seed’ is an intriguing track, ostensibly a song about getting ideas in your head. Its author grins at the thought. “It’s about stuff you know you shouldn’t be doing but you just keep doing it anyway. C’mon, what’s life if you’re not a bit naughty … I bet people who aren’t naughty, if they get to the end of their days, they probably think ‘I wish I was naughtier!’”

Pro Tools proved a beneficial but frustrating tool. “When we did I Believe You Are A Star with Pro Tools, I didn’t know you could shift [it] around block by block, bar by bar, so I actually shifted everything around on that record by ear … I had to sit there and nudge everything by a tenth of a second, so everything on that record is a wee bit out of time.”

During recording sessions, a different shift happened: Carter parted with Flying Nun. “Flying Nun had become just another record company … and it was just the same old record company shit, to be honest,” he explains frankly. “It was time to move on … to their credit, they had financed the failed recording of the album.”

Carter met Malcolm Black, the A&R staffer at Sony in a record store a couple of years later, and after sending him some demos, Sony signed Carter, and financed I Believe You Are A Star, including the installation of a Portacom studio for his back garden, neatly delivered by crane. He loved his new studio environment. “Sony actually put a lot of money into that record just purely because it took me so long to make it ... they bought a Portacom building, they craned it in, that was a great moment. Those sheds are actually very metallic, so you can hear this cheap sort of reverb through the entire record, which I kind of like.”

Reading the media from the around the time of the release of I Believe You Are A Star, a lot was made of the gap between the first Dimmer EP and the album. Carter’s irritation at repeatedly being asked that same question shows, telling Pavement magazine in 2001, “I knew that was going to be the question … and I haven’t brought my Xeroxed reply.”

However, he was busy during those seven years. Apart from creating the first Dimmer single and EP, Carter jammed with King Loser, and played guitar on their B-side ‘Exit the King’. He played on Alastair Galbraith’s 1998 album For Free, recorded ‘The Name Of The Game’ with Fiona McDonald for 1995’s ABBA tribute album Abbasalutely, and completed the (legendary) second Rim Shot Frenzy song ‘Song for Lou’ with Roy Colbert. Sporadic live performances and the first Dimmer appearance at the 1997 Big Day Out also kept him on the radar, although the release of I Believe You Are A Star put him back in the public consciousness. However, the constant comparison between his new music and Straitjacket Fits did irritate. “It seemed to mystify a lot of people, but to me … there’s a thread between all of it … it’s a continuation, and a variation on a style.”

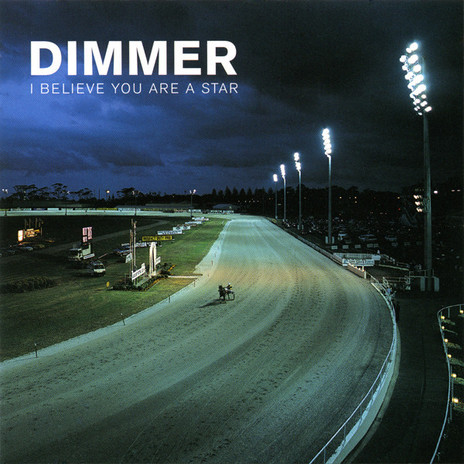

‘I Believe You Are A Star’ was a triumph critically, and is still considered Carter’s “masterpiece”.

I Believe You Are A Star was a triumph critically, and is still considered Carter’s “masterpiece”. He agrees it’s his best album. “It’s still actually my favourite record I’ve made. I didn’t want to make a rock record, I just wanted to make a beautiful record on that one.”

The critics agreed. Gary Steel (Metro, 2001) gave it high praise. “I Believe You Are A Star is … possibly one of the most original, daring, and outrageously well-defined pieces of musical art to have emanated from this country.” The album was jam packed with ideas and inspirations, and Carter admits it is “the only record I’ve ever made where I deliberately wrote a record.”

He thinks this is where the Dimmer introversion started, as “the songs on that Dimmer record were all constructed singing lightly, little-y, and small-y into a microphone in a Portacom shed at night on my own, with no band and no loud drums, and getting off on the fact that I could actually whisper. It was, he says, a minimal way to make music. “Minimal with the notes, and minimal with the volume … learning how to use space and silence … there is this strata, a subtlety to it. It didn’t reach out like a lot of my brasher music did, but I found it more interesting to find a power without using any power.” By now the fluid Dimmer lineup revolved around Carter and drummer Gary Sullivan (formerly of Jean-Paul Sartre Experience), with Nick Roughan, Andy Morton, Tom Watson, Bic Runga (singing backing vocals on ‘All The Way To Her’), and Tristan Dingemans (HDU) adding parts on the album.

Some songs on the album came to be closely identified with Dimmer, including the soul-electronica ‘Evolution’, with its Elvis ’68 Comeback Special homage video (directed by Darryl Ward) showing the four ages of Carter, with his father playing an older incarnation of him – especially poignant, as he passed away not long after the video was shot. A second was the title track, with its insistent drum and bass, and a video where Carter realised a lifelong dream as a harness-racing driver, telling Real Groove in 2001 it was “a life highlight … when I draw up the top five, that’ll definitely be in there … looping the field at Alexandra Park.”

‘Drop You Off’ is another, with an ominous video that reflects the ambiguous lyrical content. “It was written about a relationship break-up,” Carter explains. “At the same time I read the James Ellroy book My Dark Place, which was about his mother, who was abducted and murdered … the whole song, it’s supposed to be sinister – it can be about the James Ellroy book, but it’s also about … knowing you’re going to break up with someone, and they don’t know, and how shitty it is … I like uneasiness … I love the implication of stuff going on under the surface.”

The New Zealand-only release of I Believe You Are A Star saw the album chart in the Top 20, but sales weren’t stratospheric, and Sony let Carter go. “Without tooting my horn, that’s a fucking classic record … record companies … they have to have a frame of reference to put you in … with Dimmer, they had no frame of reference whatsoever,” he says. “Your job as an artist is to see beyond those barriers, to try and invent something beyond … what everyone else is doing.” However, Malcolm Black had a different take, telling New Zealand Musician in 2004 that Sony releasing Carter was more to do with a lack of international pickup for the album, citing a common response from Sony affiliates as “there are no radio singles” regardless of how much they loved it.

But, onwards. A short local tour to promote the album, and then a new label beckoned for Dimmer, Festival Mushroom Records (FMR), who in 2004 released the next album, You’ve Got To Hear The Music. This was a different beast altogether, with a snappy lead single (‘Getting What You Give’), vocals that felt smooth as silk, and a soul inflection permeating the entire record. “I was really into Al Green and Marvin Gaye at that point,” Carter muses. “I wanted to … do a subtle sort of soul-infused thing. I was completely over rock music at that point.”

While not so much an exercise in electronic experimentation, You’ve Got To Hear The Music was an album both bold and tender, with tracks like ‘Only One That Matters’, ‘Lucky One’, and ‘Finality’ providing moments of hushed, fragile quiet among the grooves. The groove was set from the start with the track ‘Come Here’, one of Carter’s most overtly sexy tracks. “It’s meant to be quite steamy, that one … that is sexy, someone saying ‘come here’, so I thought ‘okay, I will.’” he says.

You’ve Got To Hear The Music features 19 musicians other than Carter, including Anika Moa singing harmony vocals with Carter, creating a balance of sorts. “I wanted to get a feminine element into the vocals … where you have men and women singing the same kind of tunes, and so the lyrics become this universal story that can apply to anybody.” Carter has nothing but praise for Moa’s technique. “She nailed every song on the first take. She’s got incredible pitch … she’s got a musical purity to what she does.”

The soul-infusion on You’ve Got To Hear The Music worked, with the album going gold, and winning two New Zealand Music Awards (for Best Rock Album, and Best Group), and Carter has fond memories of the awards night, admitting “I don’t place importance on New Zealand music awards, but let’s just say I thoroughly enjoyed those two.” His description of the album as “campfire music for warped little souls” still intrigues, which he explains as “lots of the songs … had some sad, kind of pathetic groove to them that you’d sit around the camp and lamely clap your hands along [with] … [a] kind of organic campfire groove thing.”

The album was released with a bonus live acoustic disc recorded at a Live at Helen’s (RNZ’s Helen Young Studios], which Carter considers a favourite Dimmer recording, having “great duos with Anika of ‘Case’ and ‘Lucky One’ that I think are far superior to the recorded versions.” The recording also includes a sublime version of Straitjacket Fits’ ‘If I Were You’, which fits well within the set.

A tour followed, and in 2005, two completely different things occurred: the Straitjacket Fits reunion tour, and a request from Bic Runga to sing backing vocals on her Birds album. These coincided with a relationship break-up, which formed the basis for the next Dimmer album, There My Dear (2006).

Inspired by the concept of break-up albums, There My Dear has Carter mining his experiences for his art. Jeff Harford, talking to Carter for the Otago Daily Times in 2006, pondered to him that the songs loosely follow the seven stages of the grief, to which he replied, “It’s like a cycle … the last tune is a kind of resolution.” He expressed humour for the situation, telling Harford “I thought I would make it obsessively about the same subject. That was our big joke making it, actually. Each song was like (clenches fist and sobs pathetically), f… you.” Carter still has a similar view on it. “I thought … I’m just going to be obsessive, and completely naked about it, and just write about where it was, and what it was. It was very blunt.”

The Straitjacket Fits reunion tour was important for the direction of the album’s sound. “I think that gave me the idea to make just an immediate guitar record … with Dino [Karlis], and James Duncan, and Justyn Pilbrow played bass,” Carter remembers.

The songs were written quickly over a month. “Bic took me, Anna [Coddington], and Anika on holiday to Mahia … that’s where I had really full on experiences with Bic standing on the beach at midnight, and she’s seeing bodies in the deadwood, and I was crying about my break-up to the ocean. That’s where I wrote that song ‘What’s a Few Tears to the Ocean’, which was a mantra.”

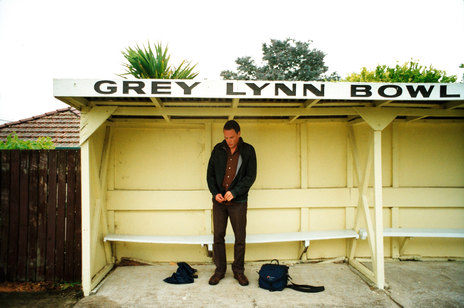

The album was completed in Dunedin. “I came down and finished it off writing it in my dad’s old cottage by the river in Brighton … facing a fire, with the river at my back, “and recorded with a live band (the core of Karlis, Duncan, and Pilbrow) at the Grey Lynn Bowling Club, utilising the backing vocal trio of Moa, Runga and Coddington. There My Dear (released on Warners) mixed highly charged rock songs (‘You Don’t Even See Me’, and ‘Scrapbook’), with sparse, raw acoustic tracks (‘Mine’, and ‘You’re Only Leaving Hurt’).

Carter says ‘You’re Only Leaving Hurt’ emerged almost fully formed, one that “completely [dropped] out of the sky … I wrote that one in 25 minutes … it was just there on the tip of my tongue,” and was what he considered the other side of the story to the more visceral ‘Scrapbook’, another song he rates highly. There My Dear was successful (No.7 on the album charts in July 2006), although Carter is sceptical of the numbers, laughing “you know, New Zealand [that means] selling 150 copies. I’ll take that with a grain of salt!”

An aside: while there has never been a full Dimmer compilation, in 2006 Rogue Records in Australia released a Dimmer primer, It All Looks The Same At Night, which sampled tracks from I Believe You Are A Star, and You’ve Got To Hear The Music, and included a DVD of the accompanying promotional videos.

Post There My Dear, Dimmer went global, touring the US and Australia, honing the sound, and (as Carter told New Zealand Musician in 2009) “[getting] the full power of the band in there.” By now, Pilbrow had left, replaced by Duncan’s Punches bandmate Kelly Steven, and Dimmer’s fluid line-up of Carter, Duncan, Karlis, and Steven would remain relatively consistent for the next two years. Returning to the US was especially enjoyable, and the band played at the 2007 South by Southwest festival (SXSW), amongst their other shows, before heading to Australia later that year. Further local shows followed, and the band played at the Wellington Homegrown Festival in 2009.

It was this line-up that went into the studio for the final Dimmer album, Degrees Of Existence (2009), although Dino Karlis moved to Germany part-way during the recording, and was replaced by original drummer Gary Sullivan, and Die! Die! Die! drummer Michael Prain (whose album Carter had produced in 2007). Carter was especially pleased with this line-up. “That band had actually played together, whereas the musicians on the other records were brought together for the records, or individual songs. We’d done quite a bit of gigging together … that was just a real live record.” He has high praise for his bandmates. “I love that incarnation of the band … because we had a few mutual experiences under the belt, we’re quite close to each other … I’ve played with James for over 10 years now, so he’s been a really great musical ally.”

The connection between the band members showed, with Degrees Of Existence (again released by Warners) considered the tightest Dimmer album. The album was a full-on rock record, with the twin guitars of Carter and Duncan circling round each other, or providing a dual attack to the senses. There was no slouching in the songwriting either: the title track was shortlisted for the 2009 APRA Silver Scroll Award (reimagined on the night by Demarnia Lloyd of Cloudboy); ‘Comfortable’ was a deceptively understated song on a new relationship; while swampy, moody centrepiece ‘Dark Night of Yourself’ revealed much about a complex, dislocated personality, and is one Carter relishes performing. “‘A ruckus in the playroom, I guess you’re just a natural naughty boy’ … I take real pleasure singing that one,” he laughs.

‘Degrees Of Existence’ received rapturous reviews.

Nominated for Best Rock Album in the 2010 New Zealand Music Awards, Degrees Of Existence received rapturous reviews. Graham Reid called it, on his Elsewhere website, “better and more consistent than the Dimmer debut … a real keeper of depth and intensity”, and it was rated among the best albums of the year in the New Zealand Herald.

With other things occurring, Carter decided to end Dimmer in 2012. “I played Laneways [in 2012] … as Shayne P. Carter, as I was going to play my whole back catalogue, ’cause I’d done the Last Train to Brockville shows,” he recalls. “I called Dimmer ‘Dimmer’ because there was something creepy about calling it Shayne Carter ... I thought I’ll just give it this umbrella name, Dimmer, and it’s essentially me … with whomever I wanted … Dimmer was one part of what I’ve done … but [he laughs] Shayne P. Carter is not as popular as Dimmer, even though it’s exactly the same musicians, and exactly the same songs.” The final Dimmer shows – in which the band’s line-up was Carter, Sullivan, Duncan, and Vaughan Williams – occurred in May 2012.

Or so it seemed. In January 2018, Carter announced a one-off reformation of the Carter-Duncan-Williams-Sullivan Dimmer line-up (with special guests who may happen to be two former members of Straitjacket Fits) as one of the last gigs at the legendary Kings Arms pub.

For the man who wrote “backwards is backwards to every degree,” is this looking back counterintuitive to his forward momentum? Carter is philosophical in his response. “I’ve probably got over that, and I don’t know if backwards is still backwards, but hey, come on, it’s the human prerogative to be able to change your mind, isn’t it?”

'Mine', 'Pendulum', and 'Degrees of Existence' were performed with Don McGlashan as part of the Carter/McGlashan 2016/2017 tours, and re-recorded for the accompanying album available only at the shows.

Carter's longtime friend and former flatmate, Graeme Downes (The Verlaines) scored the string parts for 'Only One That Really Matters'.

Sub Pop

Sony

FMR

Warner Music

Shayne Carter - vocals, guitar, keyboards, bass, production

Gary Sullivan - drums

James Duncan - guitar

Justyn Pilbrow - bass

Dino Karlis - drums, percussion

Michael Prain - drums

Vaughan Williams - bass

Kelly Steven - bass, flute

Lou Allison - bass

Ned Ngatae - guitar

Andrew Spraggon - bass

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air