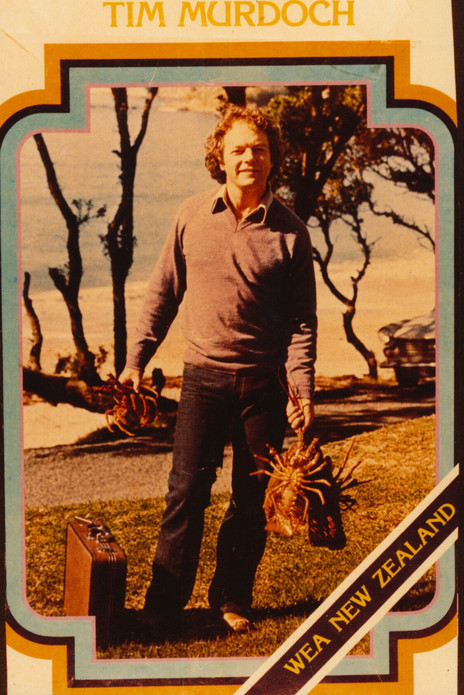

He was a gourmand of life: he loved to party but his special passion was for music. In 1977, aged 34, he became the youngest president of the New Zealand Federation of the Phonographic Industry. “My parents didn’t have a record player or a television,” he told the Auckland Star. “They thought they would be disturbing influences.”

Murdoch, whose family shifted to Auckland in the mid-1950s, attended the private school King’s College, but this privileged education was not reflected in his office catchphrases such as “sell more fucking records” and “this is going to be fucking huge”.

His musical journey started with jazz: leaving school, the first album he purchased was by jazz trumpeter Clifford Brown. But in his 1980s heyday as a record executive, his local A&R choices also reflected a respect for musicianship and fine voices, leading him to support Māori and Polynesian pop and soul artists such as Annie Crummer, Herbs, Pātea Māori Club and Ardijah.

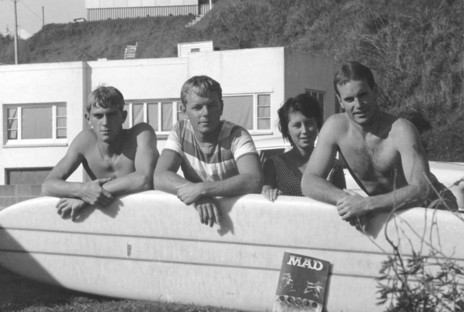

Murdoch was already leading a colourful, high-achieving life before he entered the music business. From the early 1960s he was a pioneer in the New Zealand surfing scene, appearing in the 1966 surfing documentary The Endless Summer, which became an international cult hit. Murdoch and his surfing buddy John Paine hosted US filmmaker Bruce Brown when he visited New Zealand in 1964; at the time all three were in their early 20s. (A link to the section of the film featuring Murdoch is below.)

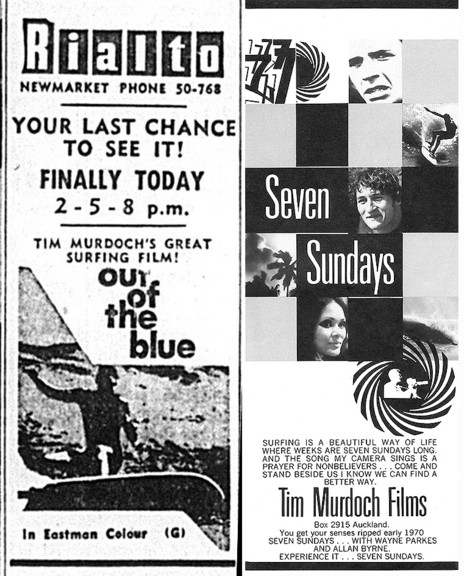

By the end of the decade Murdoch directed two New Zealand 16mm surf movies, Out Of The Blue (1967) and Seven Sundays (1970). His love of the surf even led him to be a published poet in the Auckland entertainment magazine Playdate.

The sea never speaks

In fact, it’s brooding and impassive.

Sounds of the endless waves

are the only sounds.

Man sees a lot of himself

in the breaking of the waves.

He sees sequences of his life

pass before him;

in the plunging crest

lie his hopes and dreams

of the past triumphs

Murdoch started surfing as a teen at Langs Beach on the east coast, and would keep a holiday home there throughout his life. He began using a hollow plywood board. and when lighter boards emerged circa 1960, he was sold on the sport. “We just went nuts on surfing,” he says in Gone Surfing, Luke Williamson’s history of New Zealand’s early surf scene. “We would drive all over the country looking for waves. We would spend weekends in the Coromandel where we would behave really badly and surf as much as we could. It was great!”

Williamson wrote: “Tim brought a different dimension to the early surf environment with his enthusiasm for photography, travel and entrepreneurial approach to the sport.”

In 1969 the 26-year-old Murdoch was described as “surfing’s prophet”.

Murdoch successfully toured Bruce Brown’s surf movie The Endless Summer through New Zealand cinemas in 1966, then went on to produce and direct his own movies. In 1969 Playdate described the 26-year-old filmmaker as “surfing’s prophet”, and praised his selling of his local surf photos to American surfing magazines plus Newsweek, Nova and Saturday Evening Post. Murdoch’s film Out Of The Blue “did banish the myth that New Zealand was a surfing backwater and our surfers timid amateurs.” Murdoch, an early and constant traveller, went to the US and sold his movie to an American distributor. (He first visited Hawaii in 1959, aged 17.)

Murdoch’s son Sean MacPherson, now a successful restaurateur and hotelier in the US, recalled his childhood to the New York Times in 2010. “I was surfing before I was born [in 1965]. My mother, Janet MacPherson, was a women’s champion in New Zealand, and she surfed while she was pregnant with me. My father, Tim Murdoch, was in that classic surfer film The Endless Summer.”

Seven Sundays starred influential local surfers Wayne Parks and Allan Byrne. The promotional poster’s hype lines read, “Surfing is a beautiful way of life where weeks are Seven Sundays long” and “You get your senses ripped early 1970”. In large type the producer is listed as “Tim Murdoch Films”, with an Auckland postal address, PO Box 2915, that Murdoch would keep and use for WEA Records.

Now capable of filming TV advertisements, he established a PR/advertising company with entertainment journalist John Berry. Among their clients was Pye/RCA Records, and the label’s owner George Wooller offered Murdoch the job of running Pye/RCA Records.

To record local artists, Murdoch founded the Family label, which released several albums. The label’s most notable signing was John Hanlon, who recorded four albums for Family from 1973. Other Family releases included Ray Columbus’s Jangles, Spangles & Banners (1972), Shane Hales’s Fire Exit (1973), and Butler’s Butler (1973).

Murdoch left Pye/RCA in 1973 when the opportunity to represent WEA Records came his way. Just as Murdoch had loved the California’s surf scene, he also loved California’s Laurel Canyon music scene, which had been cornered by the WEA group of labels. Originally standalone companies in the US, the WEA group included Warner/Reprise, Elektra/Asylum and Atlantic Records. On its roster were artists such as Crosby Stills & Nash, Joni Mitchell, Jackson Browne, The Eagles, James Taylor, Ry Cooder, Bonnie Raitt, Little Feat and many others.

From Murdoch’s first day at WEA, the opportunity to represent these artists must have looked more like a lifestyle than a job.

In New Zealand, the WEA labels were then licensed to the Wellington-based, British-owned EMI. In a 1975 Billboard WEA International’s Phil Rose explained the move from EMI in New Zealand. “We altered the relationship one year ago, which gave us a WEA entity within the EMI organisation. Now we are formalising that setup with our own corporate entity.”

Murdoch had run WEA during 1973 as managing director within EMI. Music writer and graphic artist Terry Hogan recalls looking for WEA that year to get review records for Auckland’s City News. “I walked into the tiny WEA office in an arcade off High Street, behind Whitcoulls. I introduced myself to the guy sitting at the front desk and asked if I could have a review copy of a Gene Clark album. Tim, for that’s who it was, said something like, ‘Well I don’t give out a lot of copies, but you’ve asked for the right record. Let me see the review when it’s published’.”

In 1975 Murdoch opened a new head office above Clichy restaurant, next to the Britomart bus station. EMI continued to distribute WEA out of Wellington until Murdoch moved WEA to lower Federal Street where there was room for an office and a warehouse (on the top floor, to the irritation of carriers).

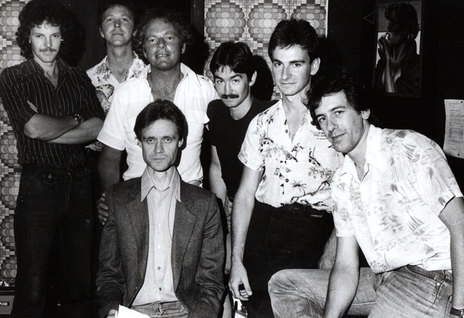

The young male sales reps at WEA looked like the musicians they were selling.

Murdoch launched the company with eight pages of advertising in the April 1975 Hot Licks magazine. The new kid in town wanted to make an impact and promote WEA as the cool company. The young male sales reps had long hair and looked like the musicians they were selling. In 1975 Murdoch hosted Joe Smith, the high-profile president of Warner Reprise in the US. A top executive visiting New Zealand reinforced the fact that WEA meant business.

With a roster that included Led Zeppelin, The Eagles, Fleetwood Mac, The Rolling Stones, The Doobie Brothers and many others, WEA looked like a license to print money. But a hiccup arrived in the 1975 budget of the short-lived Labour Government: the sales tax on records and tapes was increased from 20% to 40%. National came to power later that year but the tax remained. This wasn’t good timing for Murdoch’s start-up. It meant that executives at the record labels seriously lobbied the government, a campaign that took a decade. Bitterness about this punitive tax may have dampened record company enthusiasm for recording local music.

WEA celebrated its first birthday with a full-page advertisement in the April 1976 Hot Licks magazine. The company’s new motto was, “There’s only one place and that’s first place.” The first local signing was rock band Think, who released the album We'll Give You A Buzz in 1976. (As a member of Mi-Sex, Think guitarist Kevin Stanton would hit the jackpot later in the decade.)

When WEA made the move to Federal St, Terry Hogan dropped by and asked Murdoch if there was a job in the warehouse. “Tim thought that would be no problem,” writes Hogan. “That’s how things went. Over a period of about four years, as I moved from picking orders in the WEA warehouse, into promotions and a bit of A&R, Tim was the guy who said ‘okay’ rather than ‘nah’.”

Murdoch’s Federal Street office was famous for its clocks showing the time in Los Angeles, New York etc, with the appropriate famous executive name under that time (I presume Mo [Ostin] under the LA clock, and Ahmet [Ertegun] under the New York time). This was entirely for show as Murdoch did not need a clock to know the time in Los Angeles or New York. He was on buddy terms with the big names in WEA and its artists and, in 2010, when Trevor Reekie needed a phone number to interview Jac Holzman, founder of Elektra, he was still able to help.

When punk emerged in 1977, Fleetwood Mac sales were paying the bills at WEA: their albums seemed to occupy every record shop window. As superstar acts like Fleetwood Mac began selling millions of albums worldwide, labels wanted local representation to look after their touring acts.

“He opens his trunk and here’s this meal. I was thinking, this is fantastic, I want to come back here.”

In 1976 hip WEA act Little Feat toured New Zealand for several influential shows; 40 years later guitarist Paul Barrere recalled the visit to Nick Bollinger. He mostly remembered “how well Tim Murdoch treated us …

“You know where I knew him from? Remember The Endless Summer – the movie? I believe he’s in that movie, travelling the world and surfing. It was amazing to me that here’s this cat and he is now a bigwig for Warner Brothers! It was great because I really wanted some lamb. My dad’s French and he cooked lamb all the time, so it was kind of bred into me to get some lamb, and Tim was so struck by my insistence that his wife cooked up this beautiful leg of lamb and then he took us on this excursion all around the island, a long drive showing us different sights and so forth, and he opens his trunk and here’s this meal. So I was scarfing lamb and looking at the landscape and just thinking, this is fantastic, I want to come back here.”

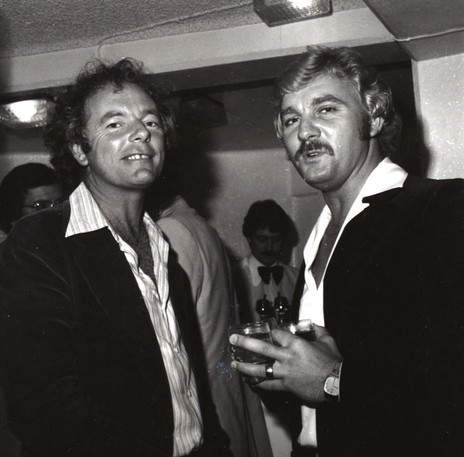

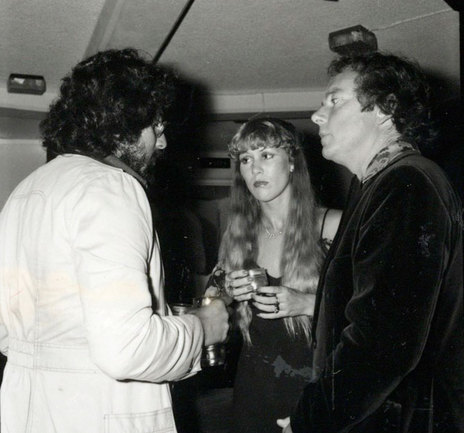

Fleetwood Mac, WEA’s golden goose, toured in late 1977 and Murdoch proved to be the host with the most; his partner Nevinka’s culinary skills became world renowned. Murdoch was soon playing tennis in Los Angeles with members of The Eagles and his new friends, and the visiting WEA executives aspired to dine at chez Tim in Auckland. Former music business rival John McCready (Phonogram, CBS) recalled, “There was no better music executive in New Zealand for looking after international touring artists than Tim Murdoch.”

A WEA employee once told me of an unusual dinner at Murdoch’s, when Stevie Nicks was the guest of honour. When the other guests sat down to eat, Nicks remained in the adjoining room, with headphones on, enthusiastically dancing to the new Madonna album: “Living in a material world, and I am a material girl …”

If, by heading WEA, Murdoch thought he’d be safe from punk, he was wrong. An A&R genius in New York called Seymour Stein started signing everything that moved in the Big Apple and soon the Sire label had Talking Heads, The Ramones and other acts disturbing the Laurel Canyon-dominated corridors of WEA. The West Coast companies got nasty too and signed Devo and The B52s, while the London office found Elvis Costello.

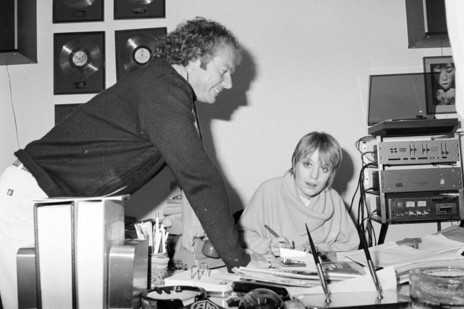

Staying hip, Murdoch had brought former Hot Licks editor Roger Jarrett into WEA’s promotions department in 1977 and, in 1978, writer Terry Hogan moved from the warehouse to work in promotions.

“Tim wasn’t sure about punk and new wave”

“Tim wasn’t sure about punk and new wave, at all, but a degree of transition took place,” writes Hogan. “When Talking Heads toured they came by the office and Tim ended up spending a bit of time with them while they were in town. Later, he told me he was relieved they were so smart and pleasant. He said, ‘I thought they were going to be really difficult to deal with’.”

With the 40% tax still imposed on records and tapes, Murdoch took the role of the president of the music industry trade organisation NZFPI from 1977 to 1988 (it would soon be renamed the Recording Industry Association of New Zealand). The industry hoped to convince the government that music was a cultural item and, like books, should not be subject to a sales tax.

Hogan recalls a crucial day in 1979: “I gave Tim a Toy Love demo tape and said ‘I think this is great, do you want to have a listen?’. The next morning Tim stopped me in the foyer and handed me the tape, saying ‘I listened to it in the car. I’m not sure I get it. But if you think it’s good why don’t you give Glyn Tucker a call at Mandrill and book some time’.”

When WEA Australia passed on releasing Toy Love, Murdoch got on the phone to Michael Browning, the former AC/DC manager who had started the indie label DeLuxe. The result: Browning added Toy Love to the roster.

Murdoch was fixated on foreign producers. Some were Laurel Canyon graduates: the scene Murdoch loved. Chris Hillman of the Byrds produced a single for a Street Talk single, and JD Souther two tracks for Jan Hellriegel. When Kim Fowley turned up in New Zealand in 1979, he was from the wrong side of the LA tracks, but Murdoch agreed to a budget for a single by Street Talk. Fowley stretched this to record a strong debut album. When Murdoch – who was holidaying at his beloved Langs Beach – didn’t show up to admire the recordings, the visiting producer got edgy. Finally, Murdoch ventured south to Auckland, just in time to be best of buddies with Fowley for a day, before the producer left town.

If there was a crash in the 1980s, the record companies didn’t notice.

The 1980s was a decade of excess; if there was a crash in 1987, the record companies didn’t notice it. Murdoch continued a steady but not prolific commitment to New Zealand releases. In 1980 Street Talk made a second album, Battleground Of Fun, and then split. A lot of the focus on recording local music drifted towards indie labels and distribution deals (in the 1990s Flying Nun would briefly be distributed by WEA). Early in the decade Hugh Lynn brought his Warrior label to WEA and had a steady run of successes with Herbs, starting with Whats Be Happen? in 1981. John Doe’s Hit Singles label had numerous releases between 1982 and 1984 including the debut single by Peking Man. Pātea Māori Club and Ardijah had success in 1987.

In 1991 Billboard announced that Tim Murdoch had been promoted to a vice-presidency within WEA International, remaining in his home territory.

Auckland music journalist Colin Hogg recalled some 1980s-era WEA largesse in his book The Awful Truth. In May 1987 he was flown first-class across the Tasman to see the Paul Simon Graceland tour. He arrived in time for a legendary long lunch. “Our numbers swelled and the accountant turned as white as the wine we’d spent all the afternoon drinking when he picked up the tab. ‘32 bottles,’ I heard him exclaim. I think it was a new record. ‘Numbers, numbers,’ snarled his boss Tim Murdoch. ‘Pay the fucking bill fergadsakes.’ ”

Murdoch’s generosity that evening led to his giving away his VIP Paul Simon seat, so he headed for the cheap seats. “Meanwhile,” wrote Hogg, “the rest of us sat in a row in the flash seats – and promptly fell asleep. Well, I didn’t. I was feeling far too lively for that … After the show, I woke up my row.”

At the Federal Street office of WEA, Murdoch held court to visitors, from an office on the top floor, with a Rolodex full of international music friends, and a state-of-the-art stereo and exercise equipment. (Employees don’t recall the latter being used.) When I was editing Rip It Up, I have two recollections of seeing the braggadocio of Murdoch at work about 1980. Both involved his showing me his responses to letters from CBS Records executives, who were seeking to unseat him as the RIANZ president.

One late afternoon, a little worse for wear after a long lunch, Murdoch said, “take a look at this.” He opened an already sealed envelope, with some difficulty, to show me a lengthy letter he’d received from the CBS accountant Michael Glading. Murdoch had responded by scrawling across the letterhead, “Get fucked”.

It seemed very rock ‘n’ roll! Then I had to watch him try and re-seal the same envelope. With a little help from a tape dispenser, he got the job done.

“He began to play bass-heavy grooves at a volume that caused promo staff to discreetly ask me to leave.”

By then he had worked out that I loved funk music, and he began to play bass-heavy grooves at a volume that caused promo staff to discreetly ask me to leave. They wanted to drive him home so they could get some work done. I was a bit slow leaving as Murdoch was on a roll playing some really good shit. I left the building thinking, that guy really knows his music, the funky stuff too.

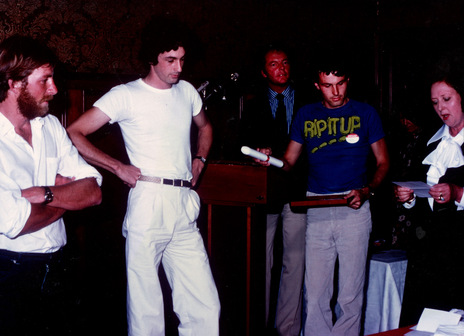

There was a squabble in 1982 over CBS artist Brendan Dugan being a finalist in the New Zealand Music Awards’ “Most Promising Male Vocalist” category (after 14 years in the industry, and seven albums). As president of RIANZ, Murdoch commented in a newspaper, and CBS was not happy. The company’s 23-year-old general manager Murray Thom sent a letter to Murdoch saying words to the effect, “The problem with our industry is the president of RIANZ saying …”

Once again I was in right place at the right time and Murdoch showed me his scrawled reply: “The problem with our industry is boys pretending to be men.”

To me, as a soul fan, Murdoch’s largesse was especially memorable in 1990 when Quincy Jones visited. Murdoch brought Jones to the country to promote his album Back On The Block. A special dinner was organised at the Orakei Basin reception room, with Quincy as guest of honour – all paid for by WEA. Ardijah and Annie Crummer performed an acoustic song or two. Quincy spoke. Fun was had by all – I am proud of my photo with Quincy – but I am told that Murdoch was never able to justify to his US superiors quite why he spent so much money bringing Quincy to New Zealand to sell a few hundred albums. Weren’t Bluff oysters good enough a reason for Quincy to make the trip? Americans, duh?

WEA was renamed Warner Music Group in 1991, and the following year Murdoch was strongly behind the release of two very successful debut albums: It’s My Sin by Jan Hellriegel and Language by Annie Crummer. But in 1994, 20 years after he launched the company in New Zealand, Murdoch’s tenure ended at Warners.

“HE ATE, BREATHED AND SLEPT MUSIC.”

It is Murdoch the music fan that Chris Caddick, a former head of EMI New Zealand, recalls: “To say Tim was a music enthusiast would be a gross understatement: he ate, breathed and slept music. He lived for the next release from his favourite artists and would delight in introducing new artists’ music to anyone and everyone. Rarely would an international artist play a gig in New Zealand without Tim being in attendance.”

The label bosses would swap releases, John McCready recalls: “We were rivals, deadly music business rivals, but friendly ones, as he ran WEA and me Phonogram then CBS. Tim would phone me all excited. ‘You’ve just got to come over, I have this great new artist’. We would meet, share the music, then go back to trying to get our companies to the top at the expense of the other.”

Jan Hellriegel liked the open-door policy Murdoch generated at Warners. In a 2012 blog she quoted a Murdoch mantra: “You are a musician, you are the reason I have a job, visit me anytime. Musicians are very important people around here.”

She adds an afterthought: “He also knew how to throw a great party.”