The image of the blue smoke drifting back to their loved ones was sad and evocative.

It was pure luck, Karaitiana said later: “He put the song in my lap. It was a natural.” The image of the blue smoke drifting back to their loved ones was sad and evocative. Within half an hour had had written the lyrics “in his head” to a melody he had already composed. He called the song ‘Blue Smoke’.

Two days later he sang it in a shipboard concert. Later in the war, there are reports of the Māori Battalion performing the song in Egypt, Italy and at informal singalongs. By 1943 Karaitiana was back in New Zealand, performing ‘Blue Smoke’ at parties, and the song seemed to take on a life of its own.

The earliest known recording of ‘Blue Smoke’ emerged in April 2019, when Sarah Johnston of Ngā Taonga – the New Zealand sound and vision archive – found a recording on a 16-inch, 78rpm acetate of the song being performed in May 1945 by the Otago Capping Sextet, just as the Second World War ended.

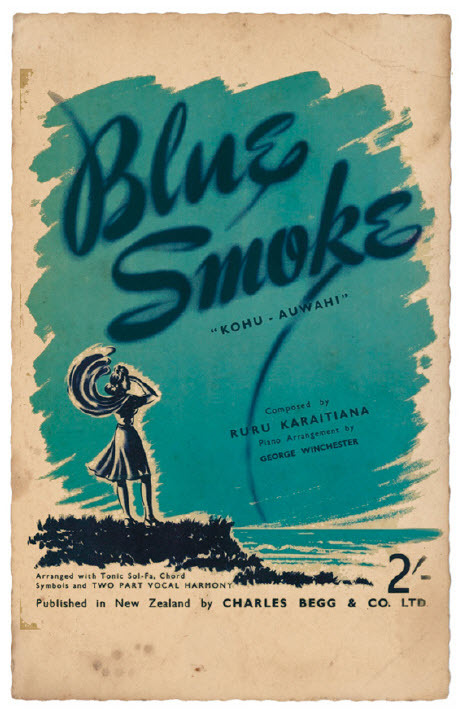

It was also recorded in 1946 by Jean Ngeru, a 17-year-old from Hāwera, who performed the song for the microphones of the New Zealand Broadcasting Service when its mobile unit visited town. The following year, Begg’s published a sheet music version, transcribed by pianist Allan Shand – Karaitiana did not read music – arranged by George Winchester.

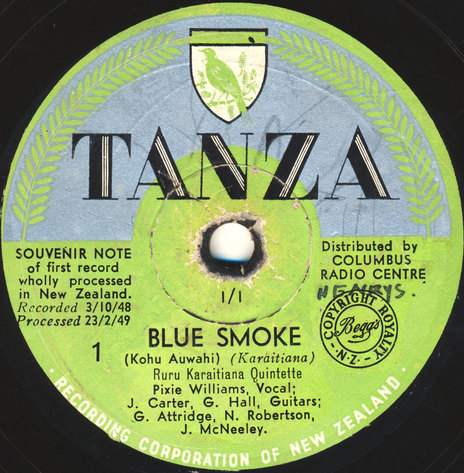

When recorded by Pixie Williams in 1948, as the first release on the Tanza label, ‘Blue Smoke’ became the “ground zero” of the homegrown New Zealand recording industry. It was the first song written by a New Zealander, recorded here and released on a New Zealand label, and it would become a massive hit.

‘BLUE SMOKE’ BECAME THE “GROUND ZERO” OF THE HOMEGROWN NEW ZEALAND RECORDING INDUSTRY.

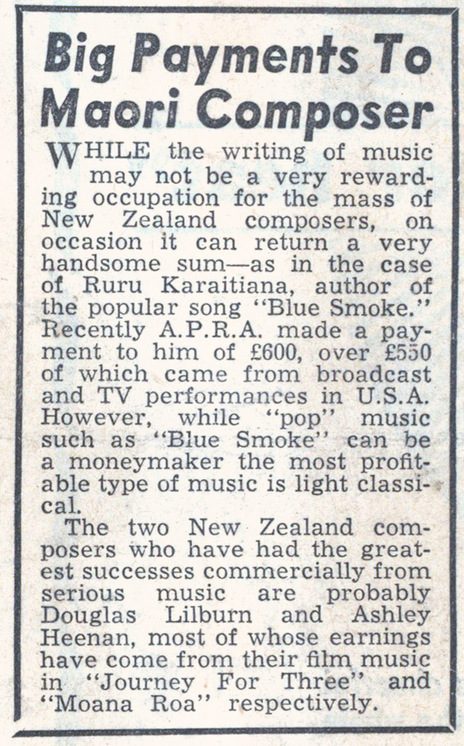

‘Blue Smoke’ was soon recorded by overseas artists such as Leslie Howard, Dean Martin, and the English duo Webster Booth and Anne Ziegler. Karaitiana would follow the song up with other compositions, such as ‘Windy City’ and ‘Let’s Talk It Over’, also recorded by Pixie Williams. In the early 1950s he travelled to the USA to chase up opportunities that proved elusive. With his family, he settled in Dunedin, where he wrote ‘Saddle Hill’ and ‘It’s Just Because’, before returning to Wellington.

Karaitiana himself never rated the song. In the files of the Sheet Music Archive of New Zealand is a copy inscribed to Shand and his band mates. It reads: “To Allan. You know Allan, I’ve never liked this song, but after you and the boys played it, I do. I would be greatly honoured if you and your boys would accept this token in appreciation. Sincerely, Ruru Karaitiana.”

Karaitiana once said that he wanted to write a Māori symphony, “but it may be many years before I am free to start”. When he died on 15 December 1970, the editor of the Dominion Jack Kelleher wrote, “I don’t know whether Ruru ever felt free to start. He continued to drift about Wellington, always it seemed on his own, a short, stocky, hesitant figure, an island in a community with musical tastes which had no room either for his vintage of pop or for a Māori symphony. He worked as a hospital gardener but was often in hospital himself …. For Māori Battalion mates, and some others, the blue smoke will linger.”

The song certainly continues to linger: when it was first released in 1949, it sold over 50,000 copies for Tanza. In 2001, when included on the Nature’s Best CD compilation of New Zealand songs, it was once again heard in nearly 100,000 homes.

–

The story of Ruru Karaitiana's groundbreaking record is explored in depth in Chris Bourke's book Blue Smoke - The Lost Dawn Of New Zealand Popular Music 1918-1964 (Auckland University Press, 2010) (pp.153 to 163).