“It’s William Clauson at the back of it all,” Des told AudioCulture in 2017, “he got that many people really enthusiastic about it. If it didn’t instill people to wish to sing, it inclined them to listen. So the folk club scene too might have got a strong impetus from that. There were no clubs at that time, but fairly soon after I would say.”

Des felt a link to Clauson and others he heard on the radio, including Burl Ives and Irish singer Mary O’Brien. “I started to really get a feel for what folk music was and started to get into it. He [Clauson] linked up with some musicians, possibly Peter Cape or one of those people. He ended up singing one or two Joe Charles poems that somebody put to music. So he was trying to pick up some New Zealand stuff. Willow Macky was a bit known at that time, he picked up one of her songs.”

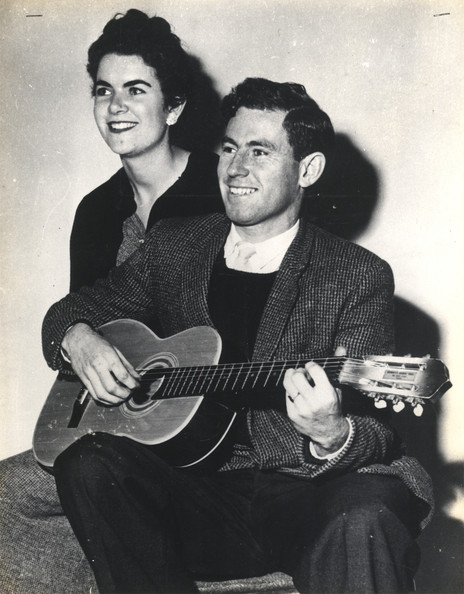

Des and Juliet’s debut performance was a duet, one of Clauson’s songs called ‘Gently Johnny My Jingalo’. “Within not very long of hearing him sing it, Juliet and I were singing it together at a Methodist church social. I remember that particular song … Juliet not wanting to sing in front of people. I said I wanted to sing it at the social and if she didn’t want to I’d get my sister Lana to sing with me. That was enough of a spark and an annoyance that she said she would sing it. That was our first song together in public.”

The couple quickly became hungry in their pursuit of music, and in 1958, Des and Juliet travelled by sea to the USA.

The couple quickly became hungry in their pursuit of music, and in 1958, Des and Juliet travelled by sea to the USA. Arriving in San Francisco, they bought a car and drove across the continent to Cleveland, Ohio, where Des studied psychology at Western Reserve University.

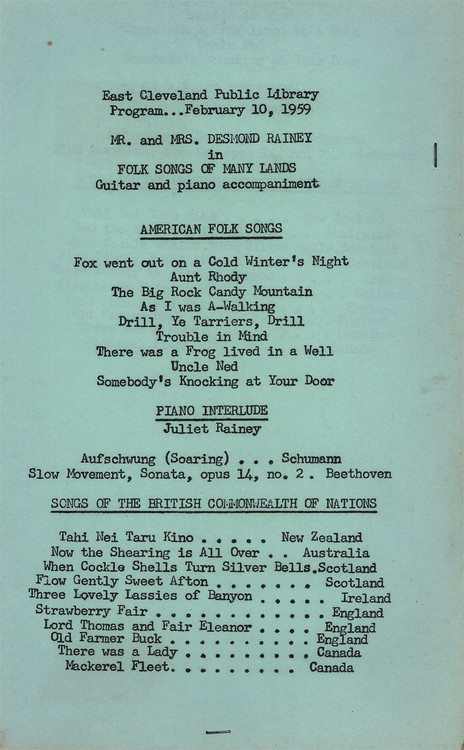

“At that stage I already had an interest in folk music so when I got to Cleveland, and since we were already singing as a couple, we were doing quite a lot of engagements around. Curiosity you know, singers from New Zealand and stuff.”

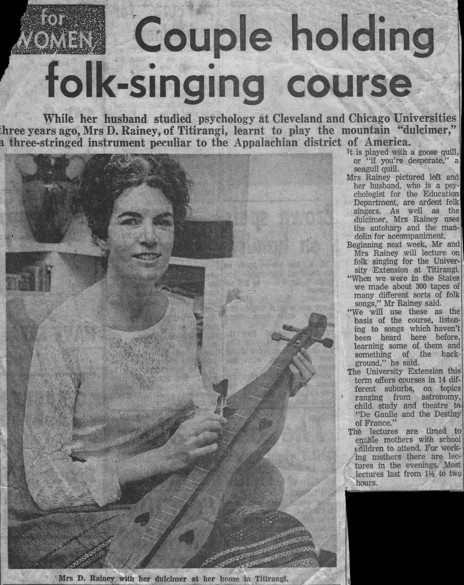

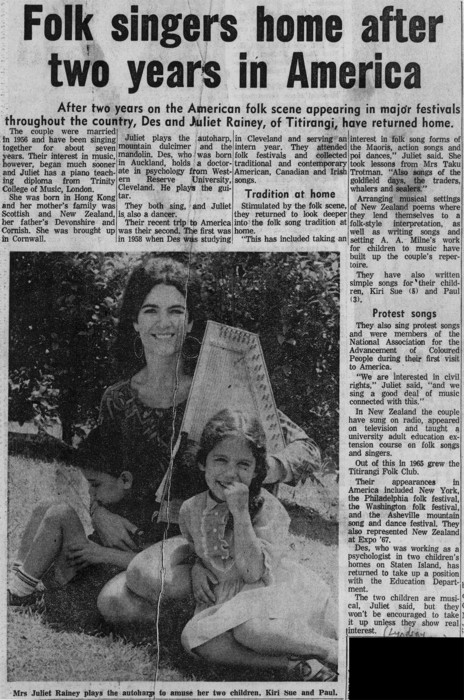

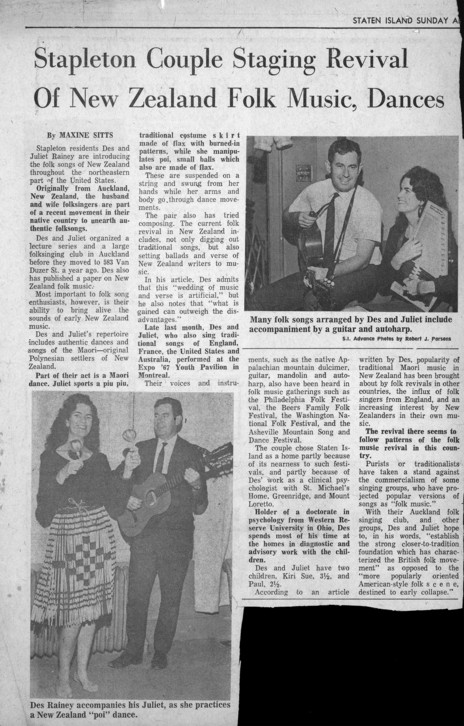

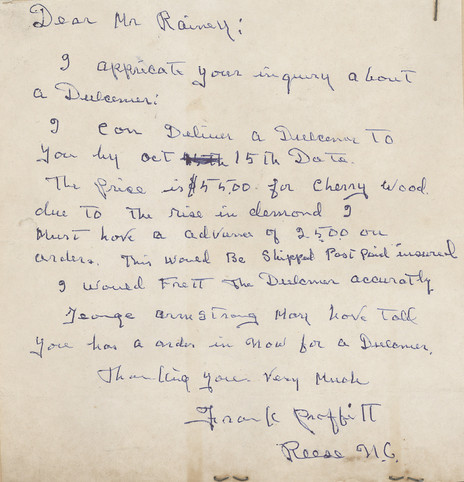

During their first years in the US, Juliet purchased an autoharp from a department store, a mandolin from a pawn shop, and an Appalachian dulcimer made by folk singer and banjo picker Frank Proffitt, who helped popularise the song ‘Tom Dooley’.

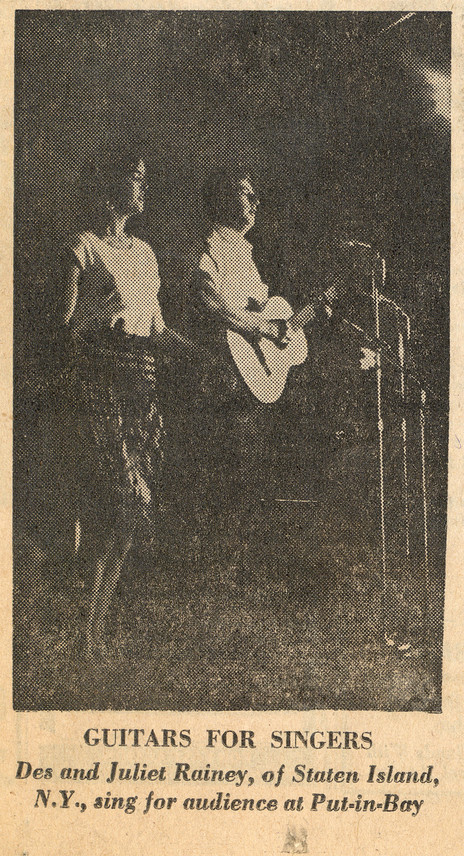

Des and Juliet collected around 300 tape-recorded folk songs during their travels, largely of Irish, American, French or Canadian origin. They spent most of their vacations travelling to folk concerts around the US, and searched libraries and Folkways label collections to listen to field recordings by folklorist Alan Lomax. “One sees some wonderful festivals on US campuses,” Des told the Auckland Star in 1965, “where there is full respect for authentic folk-singing.”

Des gained his PhD in psychology and they returned to New Zealand in 1962, when he took up a clinical psychology position at Auckland Hospital. Juliet told the Auckland Star (December 1968) that they had wanted to look deeper into the folk song tradition at home, incorporating waiata and “songs from the goldfield days, traders, whalers and sealers.”

“Before we went to America I don’t think there was any kind of folk scene,” says Des. “We were singing some songs for NZBC. Kiwi Records got to know of us. We were among several singers picked to do a series of folk music recordings for children.”

“Around this time there was no folk ‘scene’ as such but by the time we got back from my studies overseas, then there was. There were various people around Auckland who were into folk music.”

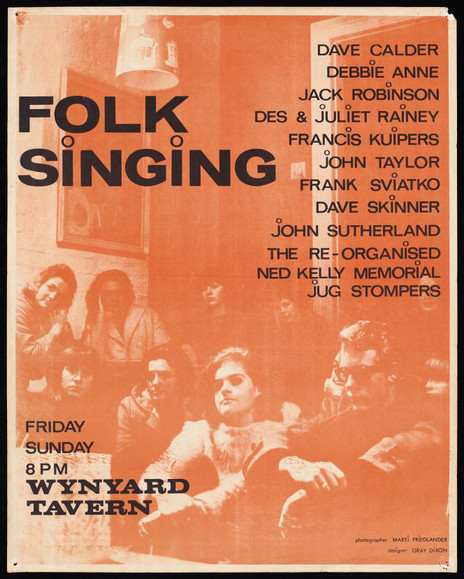

Des and Juliet sang at various folk venues, including Uptown Gallery run by Francis Kuipers in Queen Street, and the Wynyard Tavern in Symonds Street near the University of Auckland. “People from the university interested in folk would gather there,” says Des. “Poles Apart started up in Newmarket, in Khyber Pass. There was a definite scene developing. When we started the Titirangi club, we knew these people and we would invite them along as guests to sing.”

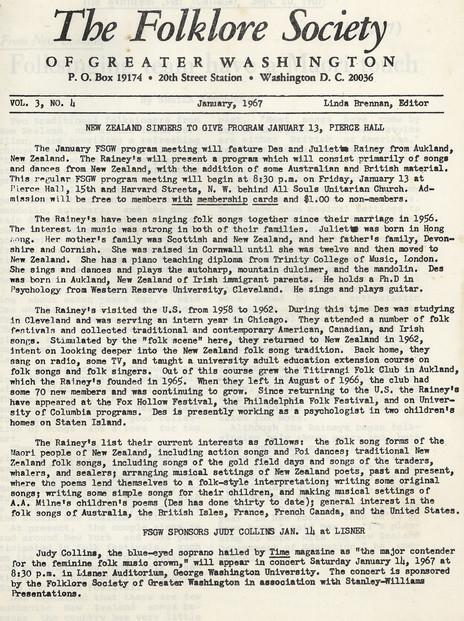

The Titirangi Folk Club grew out of a “University Extension” continuing education course started by the University of Auckland in June 1965 called “Folk Songs and Singers”. It was organised by David James, a past president at the Oxford University Folk Music Club, and presented by the Raineys.

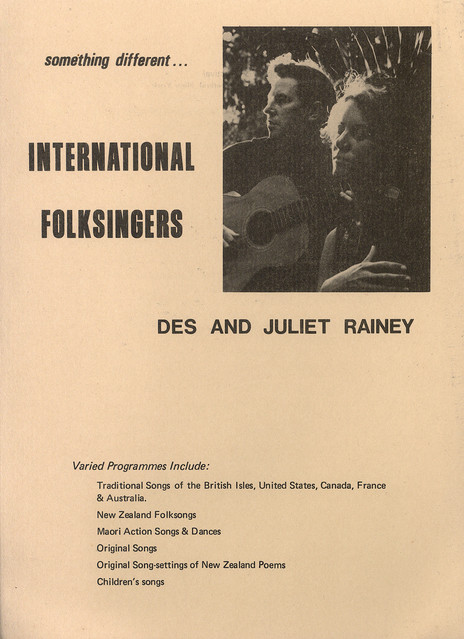

From the 1965 University Extension Prospectus: “In recent years recordings of great folk singers have created a revival of interest in folk music. But folk songs are by definition songs for and about ordinary people, enjoyed most when sung and not merely listened to. In this course, Mr and Mrs Rainey (Des and Juliet) will introduce students to folk songs and singers from many different places and teach them how to sing the songs themselves. Their repertoire includes songs from the American North, West, southern mountains and backwoods, and from Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, songs of the American Negro and Creoles, and ‘contemporary’ folk songs, such as those associated with the American Negro Freedom Movement. During four years abroad Mr and Mrs Rainey studied folk singing in Britain and the USA. Mr Rainey plays the guitar and Mrs Rainey the autoharp, mountain dulcimer and mandolin.”

Des Rainey recalls that around “10 people or so” were in the folk-song class. One of the students claimed that he could bring one of the touring Clancy Brothers in to meet with them. Originally from Ireland, the cable-knit jumper-clad Clancy Brothers (together with Tommy Makem) were based in Greenwich Village and hugely influential on a new generation of folk singers, including Bob Dylan and Christy Moore. “With more and more people wanting to attend, we booked the new [Titirangi] War Memorial Hall and went so far as to advertise the event in the Western Leader. I arranged for a few singers to be present and be ready to take part.”

“The Night the Clancy Brothers didn’t come” was something very special

The evening arrived and there was a good-sized crowd but there was no sign of anyone from the Clancy Brothers. “Local singers filled in and we ended with a night of improvised singing that everyone thoroughly enjoyed,” says Des. “The night the Clancys didn’t come was something very special. We wondered if such an informal evening of song could be repeated yet somehow retain informality and spontaneity. We decided to try – and soon were organising the first of what we called Titirangi Folk Song Evenings.”

Des and Juliet ran the meetings in Titirangi church halls from September 1965 until they left again for the US in July 1966. With their two young children they moved to New York City, where Des started working as a clinical psychologist for children on Staten Island.

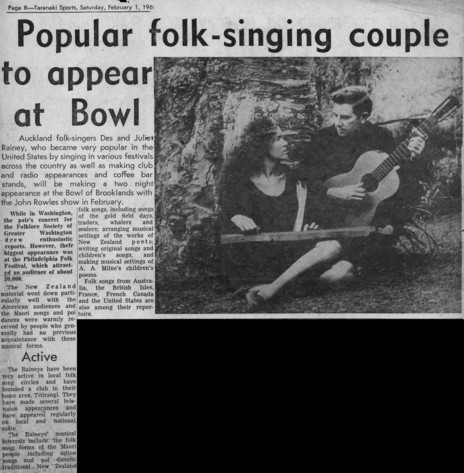

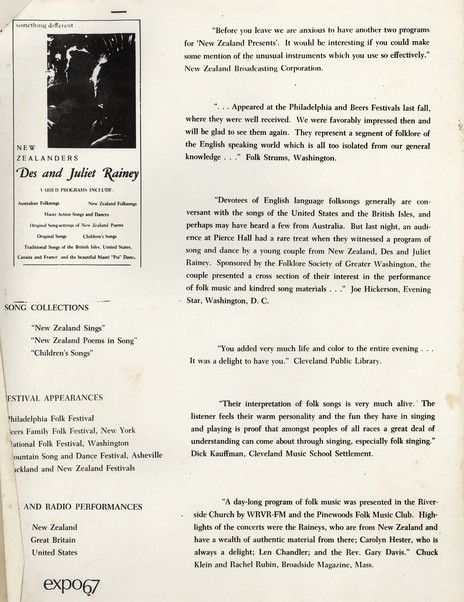

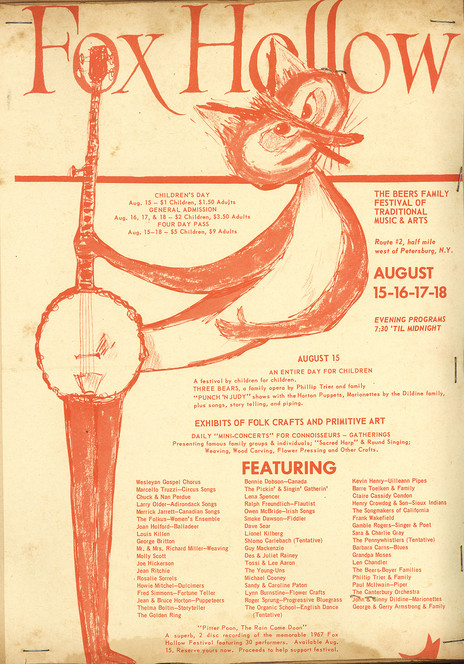

They were in high demand within the US folk community, and performed at the Philadelphia Folk Festival, the National Folk Festival, Washington National Folk Festival, the World Craft Fair in Washington, Fox Hollow Folk Festival and the Folklore Festival in New York, playing a range of folk songs from around the world. In this context they also performed waiata and poi dance; the couple studied with Mrs Taku Trotman prior to leaving New Zealand in the 1950s. “Juliet was a natural picking up the poi and dance side,” says Des.

About the Fox Hollow festival, in upstate New York, Des says, “Having driven all the way from San Francisco, we got within 200 yards of the festival and the head gasket blew. We just limped in.

“Pete Seeger was at this particular festival. One of the thrills for us, we woke up one morning to hear someone playing a recorder or flute of some sort coming through the woods, it was Pete Seeger, giant of a man. He came and had breakfast with six or eight of us.”

The Raineys also performed at Izzy Young’s Folklore Center in Greenwich Village.

The Raineys also performed at Izzy Young’s Folklore Center in Greenwich Village, a hub for the early 1960s folk revival which played a huge part in the launch of Bob Dylan’s career. “He had all sorts of people there, he was a sort of a connoisseur,” says Des. “We did a couple of concerts at Izzy Young’s; one of our best memories of New York is Izzy Young’s little Folklore Center. It was the centre of things in New York for a long time.”

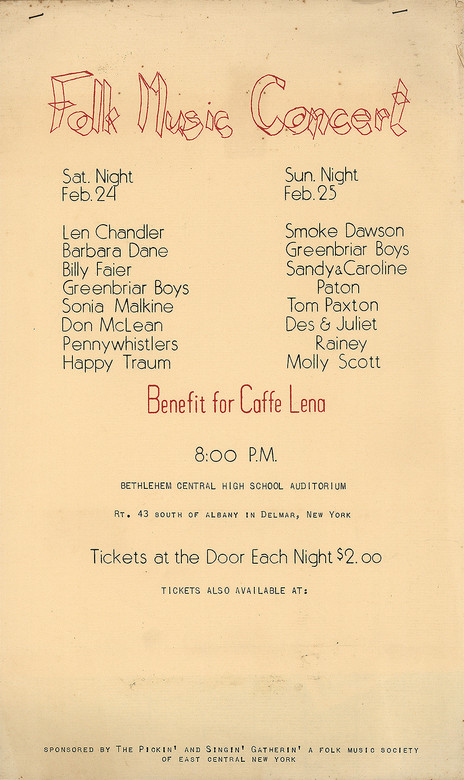

Des and Juliet played at a fundraiser for Caffé Lena in Saratoga Springs, now known as the longest-running folk coffee house in the US, and still open today. Others on the two-evening bill included Tom Paxton and Don McLean.

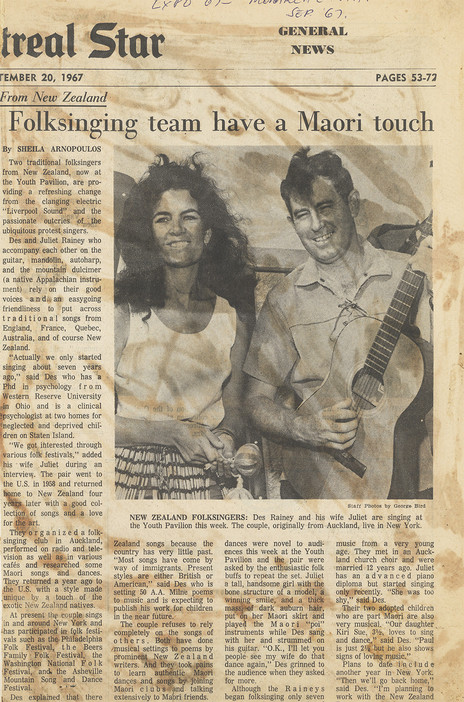

The Raineys also played at Expo 67 in Canada, one of several opening acts on the same stage as one of their musical inspirations, Odetta. The reviewer for the Montreal Star (20 September 1967) described Juliet as “a tall, handsome girl with the bone structure of a model, a winning smile and a thick mass of auburn hair.”

They had shifted to the US the second time as immigrants, says Des, “but after two years there we decided to come back, mainly for the kids to be brought up and educated in a place that we thought was better for them.”

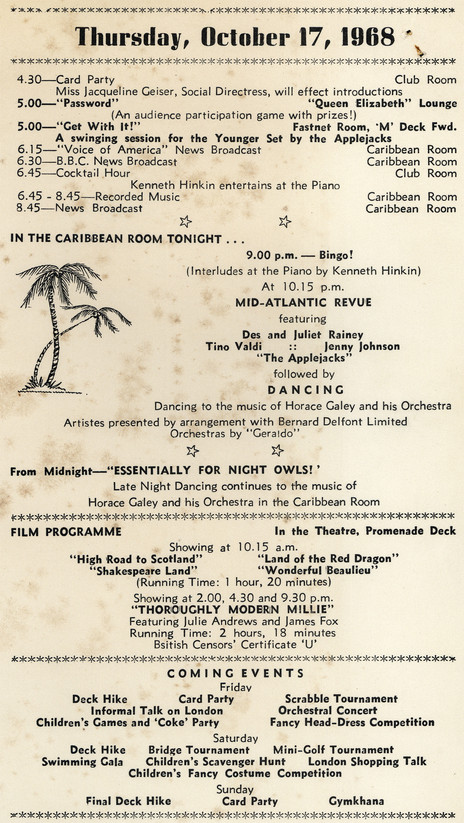

So in late 1968 they travelled from New York to Southampton on the penultimate voyage of the cruise ship Queen Elizabeth, performing several shows in England before securing passage home aboard the Oriana.

Crossing the Atlantic on the Queen Elizabeth, the Raineys partly worked their passage by performing on board. “We paid half the tourist fare and got first-class accommodation,” says Des. “They opened the door to show us the cabin … and it was huge. They said that’s for you and your husband, and then for the children they opened a door on the other side and they had a huge room also. A huge stateroom. We did no more than three or four performances on the way to England but it went all right. From England back to New Zealand we got the same deal, on the Oriana.”

While Des and Juliet lived in the US, they took part in civil rights protests; during their first visit from 1958 to 1962, they were members of the NAACP (the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People). Back in New Zealand in late 1968, Juliet told the NZ Herald, “We are interested in civil rights, “and we sing a good deal of music connected with this.” They were often asked to sing at peace and anti-war rallies.

In 1969, they sang a welcome for South African anti-Apartheid campaigner Dennis Brutus at a function in Auckland.

In 1969, they sang a welcome for South African anti-apartheid campaigner Dennis Brutus at a function in Auckland. The couple had visited Cape Town, South Africa, only a few months earlier on the voyage home. “As a part Māori family we found ourselves subject to restrictions,” Des told the Western Leader in March 1969. “For example, coloured people are forbidden to sit or stand, let alone swim, on the beaches around Cape Town. Though the authorities chose not to enforce the law, and though we half enjoyed flouting it, it was really an uncomfortable and horrible thing.” In a book Des was creating to accompany his daughter’s drawings, he wrote: “At Durban there were real lions to see and sad things not to say here.”

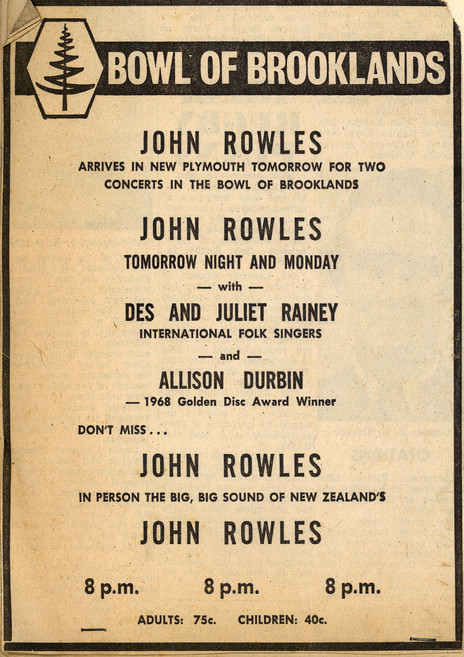

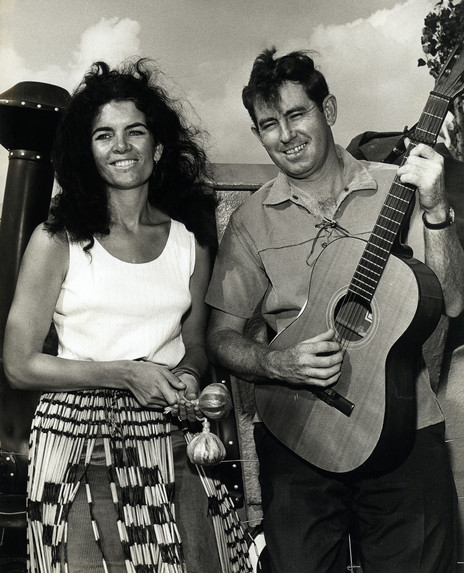

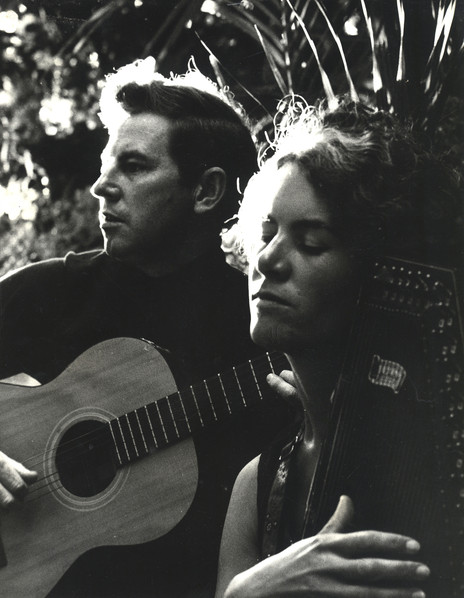

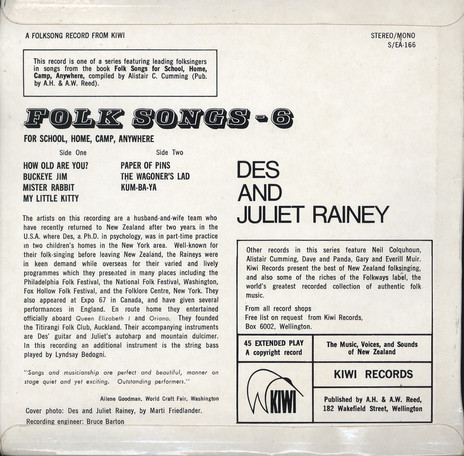

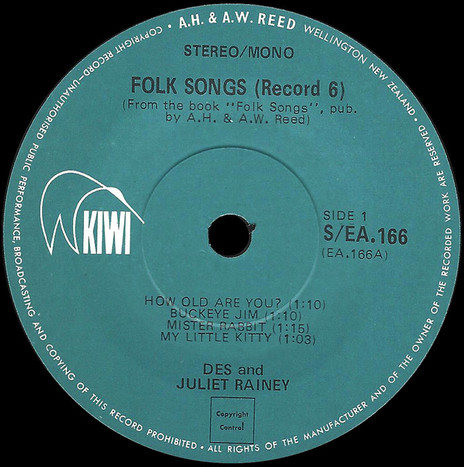

In February 1969 Des and Juliet Rainey opened the programme ahead of Allison Durbin and John Rowles at the Bowl of Brooklands, New Plymouth. The same year, they went to Wellington to record an EP of short folk songs aimed at children for the Kiwi label, Folk Songs – 6: For School, Home, Camp, Anywhere. The session was engineered by Bruce Barton and the publicity photo used on the cover was by Marti Friedlander. For this session Lyndsay Bedogni joined them on bass. “They gave us a number of songs they wanted done and that was it,” says Des. “They were lovely recordings.”

The couple appeared regularly on local radio and television, but separated in the mid-1970s. Throughout that decade, Des was Head of Clinical Psychology at Auckland Hospital. Their passion for music remained, with Juliet returning to piano as her accompaniment and Des, who worked at Kingseat Hospital in the 1980s, got into country-music activities in South Auckland. Juliet moved to Melbourne, eventually returning to New Zealand where she died in 1995.

During the 1981 Springbok rugby tour of New Zealand, Des Rainey, guitar in hand, joined in the protests against the South African apartheid regime. Des was close to the front of the large throng of protesters when they broke through the fence at Rugby Park, Hamilton on 25 July, occupied the playing field and stopped the game.

“That particular day I joined the line of people marching through Hamilton and was a long way back but by the time we got up to the ground I was up towards the front. We came to this fence, and they got stuck into it, there were quite a few people with helmets on, and stuff I wasn’t used to at all. They were busy getting into this fence. There were a whole lot, with their whole weight, pulling the fence down. People linked arm to arm started to surge onto the ground. I was among them but I pulled away and stopped, I wasn’t sure whether this was something I wanted to do, breaking in. I hummed and hawed but I thought I had to do something so I went onto the field. I must have been just in time because the cops stopped others getting in.”

The main group of protesters formed a huddle and linked arms, but Des didn’t feel part of it. He broke rank and “just walked around”. “The cops were coming out in these disciplined platoons. I didn’t want to join the big bunch in the middle. At some point I brandished the guitar towards the main grandstand but this unpleasant noise came back from the crowd and I thought, ‘That was stupid. What did you gain by doing that?’ So I thought, ‘what else could I do?’ ”

Des walked up to the police cordon, facing off eye to eye with police officers.

Des walked up to the police cordon, facing off eye to eye with police officers. “None of them stopped me, they just stood there stoically, looked straight ahead. I explained what the protest was about, why the people were there for, what they believed. I told them, they’re good people, show a bit of restraint.”

He went from one officer to the next, repeating the same line. “They regarded me as not present. They were very disciplined. One of them, his eyes told me he had responded, had heard and was with me. That was quite funny. But only one.”

Photographs of the face-off appeared in newspapers at home and abroad.

“A couple of cops came on and frog-marched me off the field. I thought they were taking me to arrest me, that I’d be in a police cell and that would be it, but that would have been better than what they did do.

“They came to a small gate in front of the big grandstand, in the left corner. The crowd there was watching the game and the cops pushed me through, shut the gate and left me in a very hostile crowd. People were trying to thump me, were kicking at me. I had my guitar, I think in front of me. It was quite scary, the crowd was seven or eight deep and I had to get through it. It was amazing; I only broke one guitar string. But it was token kind of stuff, like a ritual, they were really angry.”

Des still feels ambivalent about the style of protest during the tour, preferring peaceful protest. “But it’s not always effective,” he says.

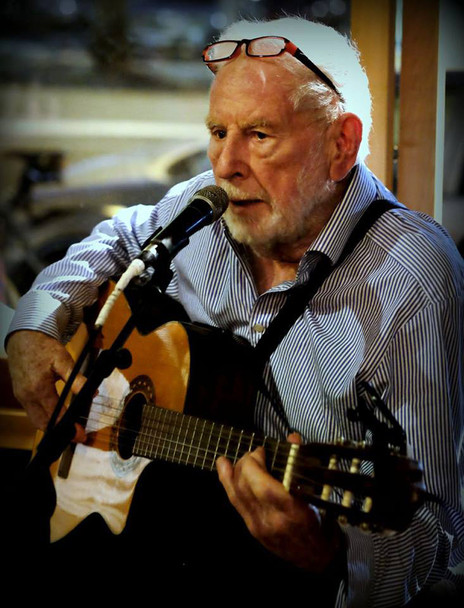

In 2015 the Titirangi Folk Club held its 50th anniversary celebration. Des Rainey spoke, ensuring that Juliet was remembered and celebrated as a co-founder of the club, and he performed a couple of songs. In 2016 Des travelled to Europe; while in Prague he recorded an album of musical and spoken word interpretations of the poems of Joe Charles. In 2017 he is still musically active as a member of the Devonport Folk Club and as a regular performer at Cafe 121 in Ponsonby.

--

Des Rainey died in Auckland on 8 January 2018, aged 87. The creative drive stayed with him until the end; he kept writing songs, a play, and hoped his musical interpretations of A.A. Milne poems would one day be released. But the message of peaceful protest through folk music still appealed to him. During his last days in hospital, Des had a dream in which Woody Guthrie came to him, and they discussed the “missing” verse in Guthrie's famous folk anthem ‘This Land Is Your Land’. The verse confirms the song as a protest song, said Des, and he recited it to those around him:

In the squares of the city, In the shadow of a steeple;

By the relief office, I'd seen my people.

As they stood there hungry, I stood there asking,

Is this land made for you and me?