The genesis of their recording sessions began in 1929, when three choir members signed a contract with Columbia at the behest of Arthur Eady, head of a music publishing firm based in Auckland. William A Donner, the manager of Columbia’s Sydney branch, toured New Zealand in the early months of 1930, where he presumably settled the deal for the Rotorua expedition. Donner must have made hasty preparations during the month after his return as he embarked on a ship bound for Auckland on 3 April. Columbia’s chief recording engineer Reginald V. Southey and musical director Gil Dech accompanied him on the trip. A portable electrical recording unit constructed in Sydney was also dispatched on the same boat.

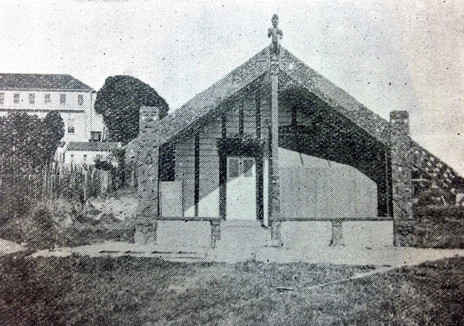

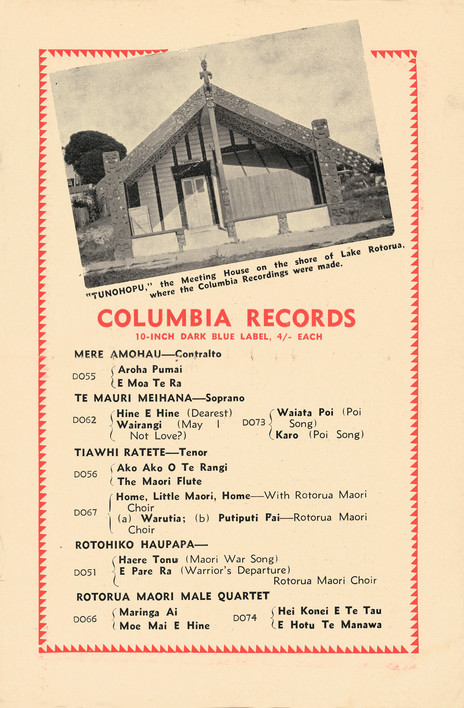

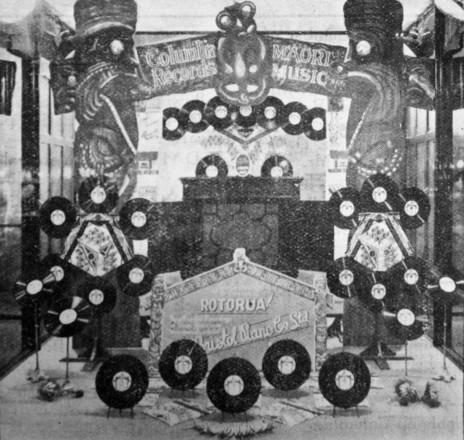

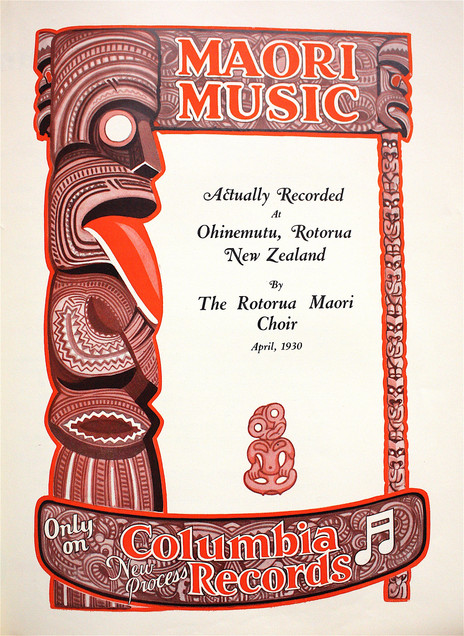

After arriving in Auckland on 7 April the crew headed straight for the village of Ōhinemutu in Rotorua. The crew set up their equipment at the Tūnohopū meeting house on the shores of Lake Rotorua. An annexe was built on the porch of the meeting house so that Southey could operate the recording equipment. The studio was described as “an ingenious erection of borrowed planks and poles”, and required the assistance of local Māori in its construction. In order to deaden the echo inside, blankets and carpets were hung from the roof and along the walls.

By the start of the first recording session on Monday 14 April, the crew had been in Rotorua for barely a week. Work started at “about 9 o’clock in the morning” and rehearsals took up most of the day. Recording then commenced at 8pm and lasted “with few rests in between” until midnight and into the early hours of the morning. This gruelling daily schedule was interrupted halfway through the sessions when the meetinghouse was needed for a burial. Southey later recounted that he turned up one morning at the wharenui but was denied entry, as the body was already inside.

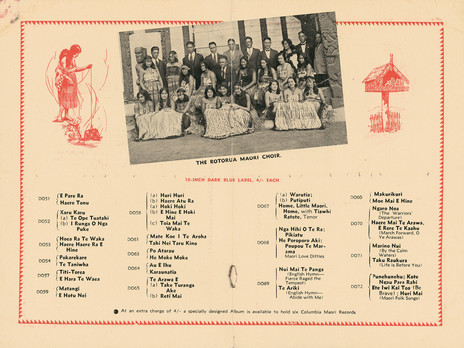

The choir and crew managed to set 51 titles in wax, clocking in at over two hours in duration.

As musical director of the sessions, Dech’s role proved challenging. At first he had to familiarise himself with the large body of songs and train the choir to sing as a group. Most of the members were accustomed to singing solo, and separate parts had to be written for individual singers when they sang in unison. Dech also struggled to manage the choir’s behaviour and gain their respect as the pākehā who “[stood] up in front of them waving his arms about”. Another reported difficulty was getting everyone to rehearsal on time, a matter that would have rightly annoyed the Columbia crew, who prided themselves on running a tight and efficient outfit.

These difficulties did not stop progress, and by the final recording date on 26 April, the choir and crew had managed to set 51 titles in wax, clocking in at over two hours in duration. The Columbia crew had spent under a month in New Zealand, and the expedition was reported as a success in newspapers and trade journals at the time.

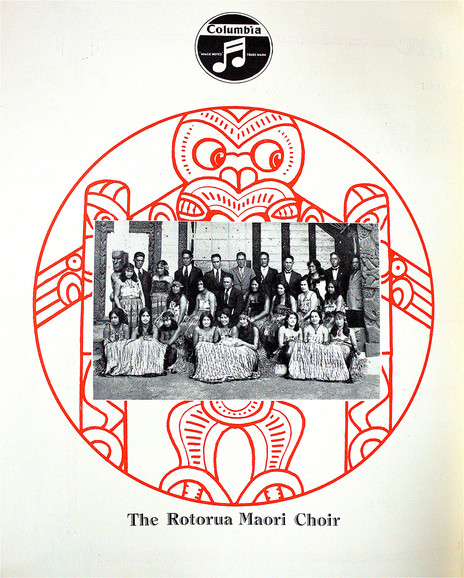

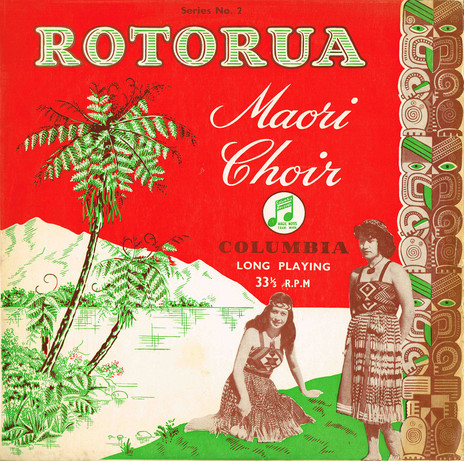

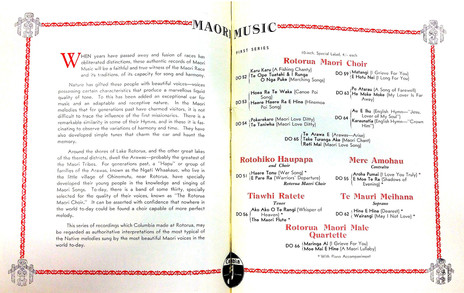

A total of 48 titles were pressed and issued on 24 discs, featuring the entire choir as well as soloists Te Mauri Meihana, Tiawhi Ratete, Mere Amohau, Rotohiko Haupapa, and a male vocal quartet. (One of the youngest singers was a 17-year-old called Kahu who would later be the mother of Howard Morrison.)

Although touted as “absolutely authentic” by Columbia on their release in June 1930, the motivations were purely commercial. Southey later admitted that many tourists who visited New Zealand asked for recordings of local singers, but that none were available.

Despite these issues of “authenticity”, the Choir and their recordings have left a remarkable legacy. Dr Mervyn McLean describes in his book To Tatau Waka how records of the Māori Choir captivated him at an early age, prefiguring a career dedicated to the study of Māori music. Jonathan Ward also advocated for their cultural and historical value in a blog post on his site Excavated Shellac, where he quipped that “when it comes to early Māori music on 78, this is what we have, and little else”.

Even after 86 years, performances by the Rotorua Māori Choir still retain their power and sway. Their renditions of now classic songs such as ‘Pōkarekare Ana’, ‘Karu Karu’ and ‘Pō Atarau’ are testaments to the endurance of Māori culture and vocal art. In 1937, choir member Te Mauri Meihana commented on the eclectic influences on Māori music, from opera, sea shanties, church music to jazz, but maintained that the “Māori spirit” had been kept intact. In words that perfectly capture the tone of the Rotorua recordings, she defines this spirit as “the yearning for the past; the lament for the days and times that are no more”.

The complete recordings of the Rotorua Māori Choir were issued digitally in 2021; the Spotify links are embedded below.