Until the success of the Moana music, which went to No.1 on the New Zealand charts, Foa’i and Te Vaka have rarely been part of New Zealand’s musical landscape. Certainly they have lived in Australia for quite a while but in New Zealand – where they have been critically acclaimed but rarely performed as they spent so much time touring overseas – their music was barely acknowledged in their early years.

“Maybe it was too familiar in this area,” said Opetaia in 2002. “People would go, ‘Huh, what do you want to do that for?’ That was the attitude here.”

But Moana has changed all that.

“I think this [film] will awaken some sort of sense of pride in people,” he told the New Zealand Herald late last year at the film’s launch. “And hopefully they will go, ‘Oh, I need to go back and reconnect and put my feet on the land and discover, find out about my roots.’ ”

And those roots reach across many Pacific cultures, entwined by language, custom and heritage from Hawaii to Aotearoa New Zealand.

The story of the pan-Pacific sound of Te Vaka began at an ordinary kitchen table in Laingholm, West Auckland in the mid nineties.

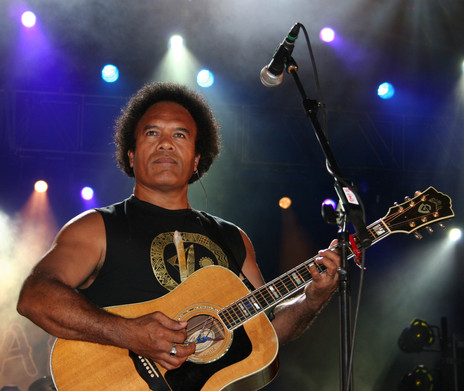

Opetaia Foa’i – chosen by Disney after they heard the band’s many albums – seems an almost obvious pick as the one to bring authentic Pacific beats, harmonies and language to the blockbuster project.

The story of the pan-Pacific sound of Te Vaka began at an ordinary kitchen table in Laingholm, West Auckland in the mid 1990s when Foa’I’s wife Julie – Te Vaka’s longtime manager – wrote something on a piece of paper and handed it to her husband and the three musicians in the nascent band.

It read, “Target: take this music to the world”.

“We looked at each other and thought, ‘This lady’s crazy’,” Opetaia told the Herald in 2002, by which time they’d done it.

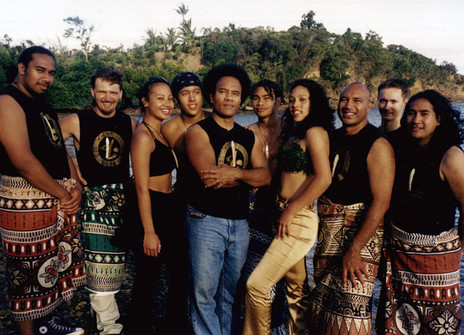

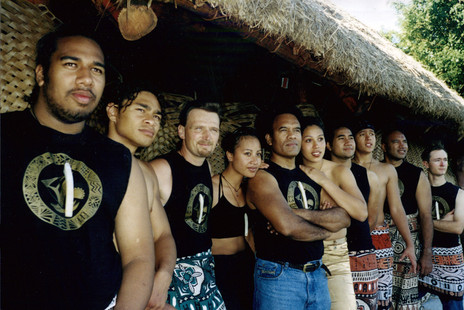

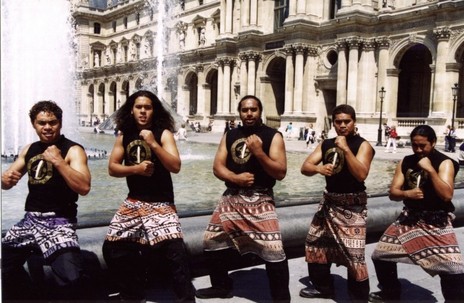

When Julie wrote the simple but seemingly impossible goal, Opetaia had grown weary of playing in a covers band and – drawing on the stories of life in Tokelau and Tuvalu which he’d heard – decided to form a group, mostly of family members, which would not only play original music inspired by the Pacific, but also feature Polynesian dancers.

Within a year Opetaia and Julie had written some songs in English for an intended album and then, almost as an afterthought, added ‘Ki Te La’ inTokelauan. Someone suggested they send it to Peter Gabriel, who was then behind his own Real World record label and the Womad festivals, so a tape was duly sent to Gabriel’s studio near Bath in Britain.

“The first thing they said was, ‘Can you send some more?’ ” Julie told the Herald.

“I didn't have any more,” admitted Opetaia, “but said, ‘Sure, how many do you want?’ Basically Julie locked me in the studio and said, ‘Don't come out until you’ve got four new songs’, which I did in a week and we sent over.”

And then the story of Te Vaka really began.

By the end of 1996 they had released their self-titled debut album on their own Spirit of Play label (repackaged by the world music label ARC out of Britain and released in 80 countries to favourable reviews) and in 1997 they appeared at the South by Southwest (SXSW) festival in Austin, Texas.

Their videos brought the exotic Pacific to European audiences, and in 1999 they performed at the Apec Conference in Auckland and had the-then US Secretary of State Madeleine Albright up dancing.

At the invitation of Greenpeace and other environmental groups they took part in demonstrations in The Hague in 2000 to protest against global warming.

“My goal,” Opetaia told the Herald, “was to write material which was something to do with the Pacific and to tell the [Pacific] story. It was always aimed at Europe because they seemed to understand immediately what we were doing.”

And given his background – Apia-born, Auckland-raised and whose ancestry is in Tokelau and Tuvalu – Opetaia seemed the right man to do that, and to carry the message of the damage climate change was wreaking on small Pacific nations.

But very quickly Te Vaka – tellingly the name means “canoe” in Tokelau, the metaphor of a vehicle to carry the stories on a journey – broke out of the exotic/world music corner and into mainstream venues and acceptance.

They continued to play at Womad but by the early 2000s could tick off rock and jazz festivals in Germany and Estonia, an appearance at Ronnie Scott’s (described in the club’s publicity as “one of the most talented and original world music acts to appear on the international scene in years”) and the Royal Festival Hall in London. By the mid 2000s they had played in 30 countries.

Over time, New Zealand audiences discovered what the local and international critics already knew.

And the albums just kept coming: Ki Mua in 1999; Nukukehe (2002); Tutuki (2004); Olatia (2007); Haoloto (2009), Havili (2011), and Amataga (2015). The most common language used on the Te Vaka albums is Tokelauan.

Over time, New Zealand audiences discovered what the local and international critics already knew. In retrospect Nukukehe seemed the breakthrough. It was nominated Best Roots Album at the New Zealand Music Awards, Best Asia/Pacific Album at the BBC Radio 3 World Music Awards and was the audience choice at the BBC Radio 3 World Music Awards.

Chris Bourke wrote in Real Groove magazine, “There is plenty of lip service paid to Pacific culture but Foa’i’s Te Vaka is the real oil: this is the canoe undertaking the great migration. To be moved by something so familiar, so pervasive it is taken for granted, is like rediscovering your own heartbeat.”

As Herald reviewer, I wrote: “Te Vaka leader Opetaia Foa’i not only has a mainline into melody but the studio smarts (with Malcolm Smith) to polish and refine the music into Pasifika crossover pop which shimmers with glistening guitars and pulses with rhythms from log drums.

“Add in the occasional children’s chorus and gorgeous vocals by Sulata and it’s a winning combination. The messages are emotional and important: ‘Sei Ma Le Losa’ is dedicated to the late David McTaggart, the founder of Greenpeace, and elsewhere are laments for what has been lost in the Pacific. Ballads such as ‘Loimata E Maligi (Let the Tears Fall Down)’ written in memory of the 19 girls killed by fire in their Tuvalu [boarding school] are hauntingly beautiful.”

Even if their albums sold in small numbers in New Zealand, they were consistently hailed at local and international music awards.

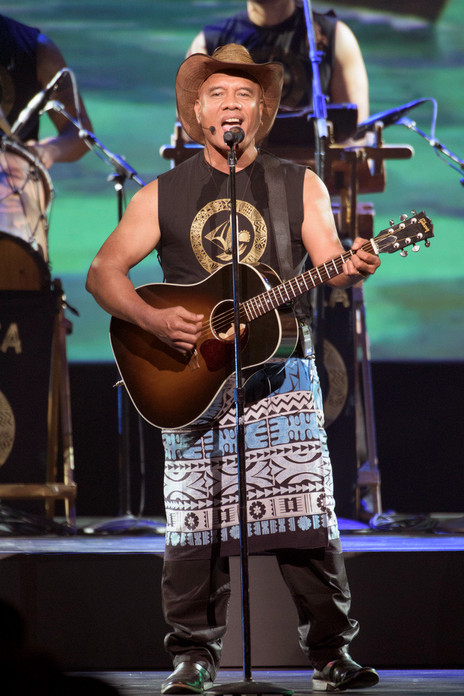

Tutuki, Olatia and Haoloto won back-to-back Best Pacific Album awards in New Zealand. Among other accolades, Tutuki picked up an award in the international category at the Australian Songwriting Awards and Haoloto was voted Best Polynesian Album at the Hawaiian Music Awards. In recent years Te Vaka have been voted Best Pacific Group at the New Zealand Music awards.

Before the global acclaim and enjoyment of the Moana album – which seems to have replaced Frozen as the soundtrack of choice for kids and their parents – the Amataga album hinted they might be riding a wave. It won Best Pacific Music Album at New Zealand’s music awards and they also picked up Best Pacific Group, Best Pacific Song and Best Pacific Language album in the Pacific Music Awards.

The global success of Moana has taken them to a level they always aimed for, even more than 20 years ago when Julie passed that note across the kitchen table.

“It was a huge responsibility taking on this [Moana] project,” Opetaia told journalist Michelle Paragan late in 2016. “People view it as being put in the spotlight and getting all this attention. For me, it was a big responsibility because I had spent 20 years promoting this culture.

“This movie is not based on a book, but the stories of our ancestors. It’s a first in many, many ways. It’s going to open up a lot of things for South Pacific music. I think this will enable people to look deeper into and be interested in the genre.”

Mostly written in seclusion in a three-month retreat in a house with no electricity near Waihi, the songs took shape and were recorded at Warner Bros Studio in Burbank, California.

‘We Know the Way’ – co-written with American Lin-Manuel Miranda, who was nominated for an Oscar for ‘How Far I'll Go’ on the soundtrack – has special resonance for Opetaia, especially when you think of the meaning behind Te Vaka’s name: “[It] means so much to me because it matched the power and the confidence that these ancestors had when they sailed the seas.”

“Right from the beginning,” Opetaia Foa’i said in 2002, “we’ve always had this target of doing something musically ... for this area. I want to sit in Paris or somewhere and have someone say, ‘Hey, that’s Pacific music’ and recognise it straight away. It is something that can go across to other cultures.

“And being on this path you realise, ‘Man, you’ve hardly even started and there’s a long way to go’. I’m hoping more people will get on this path because somewhere in a school somewhere are kids who are going to take it even further.”

They will probably be kids who have watched Moana over and over, have heard Te Vaka’s inspirational and authentic voices, and will come out of the Pacific and onto the global stage.

Because Opetaia and Julie Foa’i, their children and band members, have shown them it can be done.

Opetaia Foa’i won an award for International Achievement at the 2017 Vodafone New Zealand Music Awards. In May 2018 he and Te Vaka won the top soundtrack prize for Moana at the Top Soundtrack for Moana at the Billboard Music Awards.