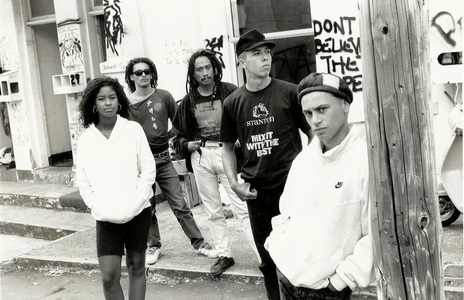

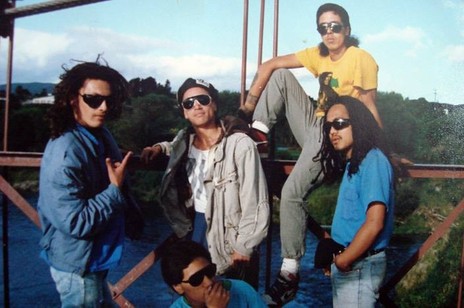

The original members are Te Kupu (Dean Hapeta, aka D-Word), MC Wiya (Matt Hapeta), DLT (Darryl Thomson), and Aaron Thompson (Blue Dread). Membership has varied, and others have added their flavours to the Posse during the band’s existence, among them MC B-Ware (Bennett Pomana), Acid Dread (Steve Rameka), Teremoana Rapley (who joined the group as a 14 year-old Heretaunga College student), Kiki Marama, Taki Matete, Earl Robertson, Emma Paki, Maaka Phat (Maaka Macgregor). UHP is currently a three to seven piece unit, with a fluid line-up centred around Te Kupu on vocals, rhythm guitar and keys, and MC Wiya on vocals and bass.

Te Kupu was shaped by an incident that occurred in Upper Hutt when he was just eight or nine years old. As he was crossing a road near his home, a biker called him a “nigger”. Understandably, this surprised the young boy, and when he got home he asked his mother, “What’s a nigger?” Until then he had been unware differences of race or ethnicity. Although it was a bad experience at the time, Te Kupu is almost thankful now for the chance it gave him to be aware, at an earlier age than most of his generation, of the racial divisions in this country. He has been growing and sharing his awareness of social and political injustices ever since, principally through his music.

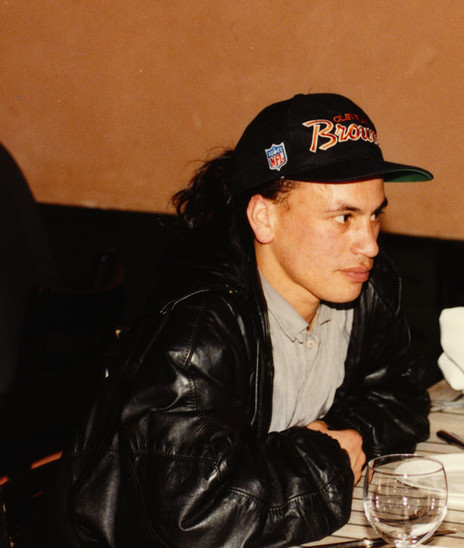

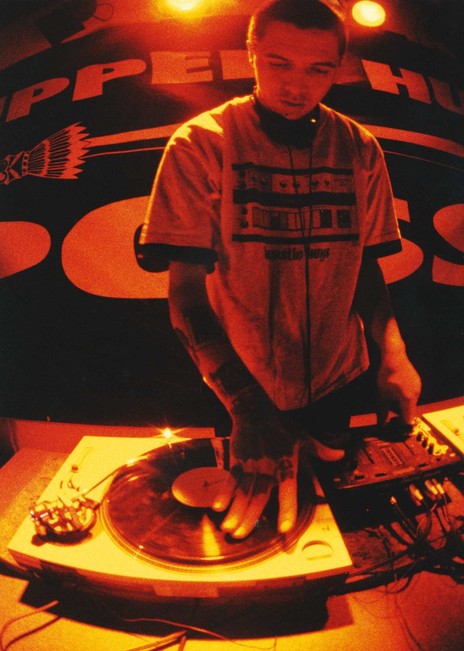

DLT – another of the group’s founders – spent his childhood in Omaha and Maraenui, Hawke’s Bay. Some of his early influences were Michael Jackson, and the The Sugarhill Gang’s ‘Rapper’s Delight’ from 1979. According to an interview he did with Gareth Shute for the book Hip Hop Music in Aotearoa, he moved to Wellington in the early 1980s and it didn’t take long before he “encountered” Te Kupu for the first time.

“It was at Lower Hutt on Thursday night – late night shopping – and I was with a bunch of guys from a different side of Upper Hutt to Dean. We came around the corner and sat down. Then we heard this argument and there’s this little short guy arguing with these big tall guys … And we just sat there and watched Dean for 10 minutes or so, just watched him say, ‘Come on … come on, if you’re gonna … do me, do me, come on!’ ... And I was like, instant respect.”

Not long after that episode they met properly and started hanging out. They were both interested in the street dance and graffiti culture developing in the US. After a period of informal jams with a few of their mates and many political discussions later, they decided to start the band.

When UHP first formed, its members were mostly inspired by socio-political music such as Bob Marley & The Wailers, particularly their album Survival of 1979 with its message of “So much trouble in the world” which Te Kupu said, “sang straight to them”. The group was also influenced by bands such as American hip hop pioneers Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, who wrote music about the social ills they saw around them in the United States. UHP indigenised it, making it relevant to young Māori in Aotearoa.

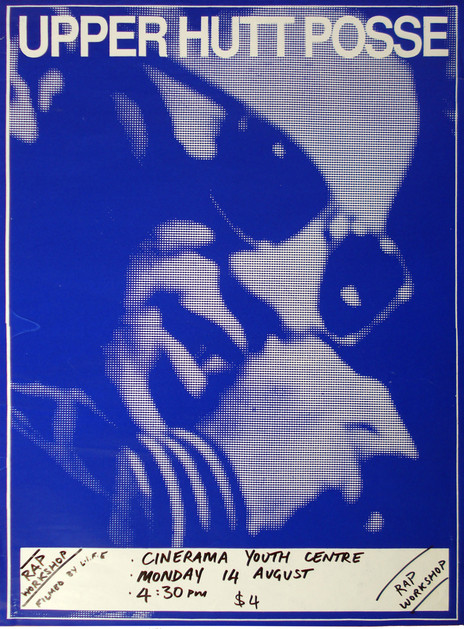

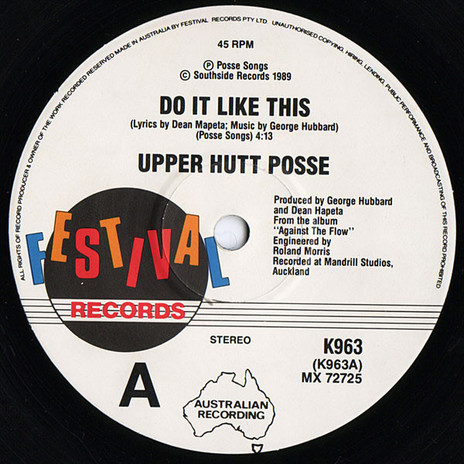

In 1987 UHP performed as non-contestants at a rap competition in Taita, Wellington. It was here that they linked up with George Hubbard, a local art curator and drum machine programmer who became their manager. Te Kupu talks of how he was impressed by the 808 drum machine owned by Hubbard at the time. Hubbard helped the band get a QEII Arts Council (later Creative New Zealand) grant which allowed the group to get studio time to record its first single. Te Kupu recalls Hubbard suggesting that the poppier style of ‘That’s The Beat’ – one of the group’s other early songs – might be a better choice, but D Word was adamant that the first release would be political and it would be ‘E Tū’.

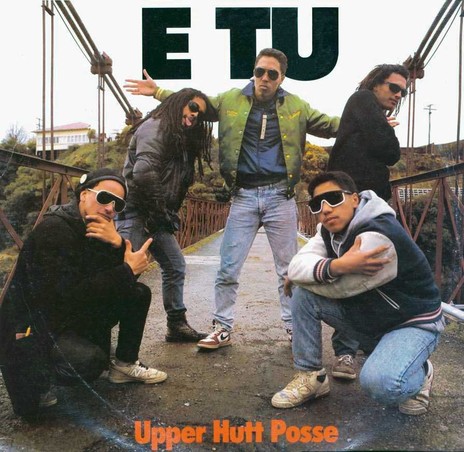

In 1988 they released ‘E Tū’ on 12” vinyl through Jayrem. It was Aotearoa’s first rap record.

In October 1988 they released ‘E Tū’ on 12-inch vinyl through Jayrem Records. It was Aotearoa’s first rap record. When the music video for this song aired on Radio With Pictures in November 1988, the band instantly became known throughout the country. The chorus “E Tū, Stand Proud, Kia Kaha, Say It Loud” was inspired by James Brown’s 1968 funk anthem ‘Say It Loud – I’m Black And I’m Proud’. ‘E Tū’ was bold in its message and like many Posse songs since, uncompromising in its lyrics. It pays homage to Māori historical figures who fought against the English in the early days of colonisation in Aotearoa in the 19th century, including Te Rauparaha, Te Rangihaeata, and Tītokowaru. The song is a call for young Māori to be proud of, and learn from, their ancestors who fought for mana motuhake and tino rangatiratanga, or independence and self-determination. The song ends with a message to continue on with the struggle: “’Cause white rule and injustice go hand in hand, so against that is where we stand. Don’t forget those who’ve fought before, our struggle continues more and more.”

On the B-side, ‘Intervention’ has lyrics about the French terrorists who bombed the Rainbow Warrior in Auckland in 1985 after the Greenpeace boat was involved in protests about nuclear testing in the Pacific. It strongly supports the banning of US nuclear ships in Aotearoa. “We don’t want your nuclear / We don’t wanna burn / I’m saying it strong / I’m saying it stern.” The song goes on to put this event into a historical and contemporary context of Aotearoa as a colonised nation: “What’re you gonna do about foreign intervention?” The B-side finishes with ‘No Worries In The Party Tonite’, a feel-good reggae song which features sequenced drum beats, and scratching in the instrumental and chorus; the record sleeve says the record is “dedicated to the fight against injustice”.

In 2016, 28 years after the release of ‘E Tū’, Upper Hutt Posse was awarded Independent Music New Zealand’s Classic Record award. One of the judges, Peter McLennan, said: “‘E Tū’ is a hugely important record, both culturally and politically. It showed local rap fans and budding rappers that we could make this exciting new genre our own, with rhyming in te reo and English, and by name-checking local history. Upper Hutt Posse are our hip hop pioneers, and they opened the gates for the likes of Dam Native, 3 The Hard Way, and Che Fu.”

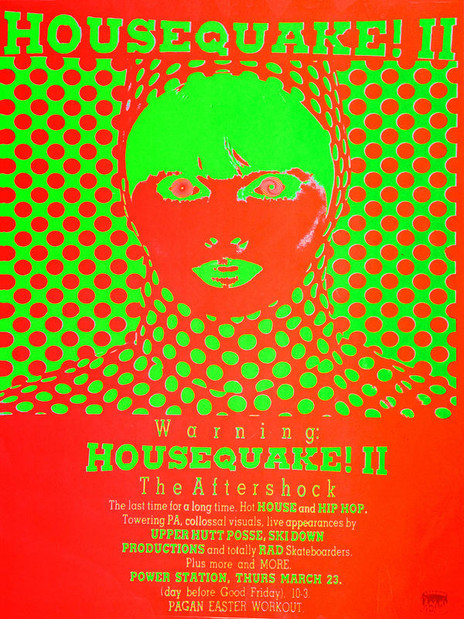

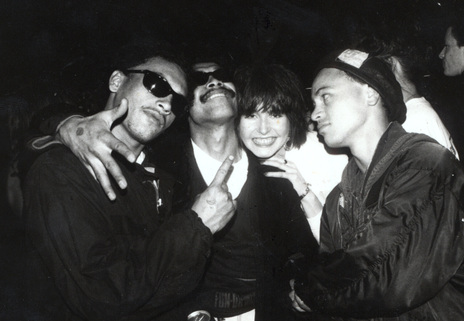

In 1989, Te Kupu, DLT, MC Beware and Hubbard moved to Auckland so they could get more exposure for their music. Wellington didn’t have the population or the venues to support the fledgling hip hop scene. However, youth culture in Auckland was beginning to be transformed by the dance party scene, which the band was able to hook into. Recalling this period to hip hop historian Gareth Shute, DLT said: “There’d be a thousand kids at a venue with turntables and live acts. So we got on the front of that and we sorta got by for a while because we were mixed up amongst Total Effect, Semi-MCs, House-party … Wellington had been a different story … It seemed exciting and pretty full-on. Good prospects.”

That same year UHP released their debut album Against the Flow through Southside Records. It was stylistically diverse with reggae, samples, sequenced beats, scratching, and also the political slow jam ‘Stormy Weather’, with rap by Te Kupu and the chorus sung by Teremoana Rapley and Acid Dread. Various people have contrasted the album’s reggae-inspired music with the more funk-inspired beats of their American counterparts. Te Kupu explained that they wanted to express themselves in a variety of ways through rap, singing, and reggae, as well as thematically doing a mix of politically “hardcore” as well as party songs. “We’d always look at Bob Marley. He does the hardest political songs with the best lyrics, but he does love songs as well. We liked that style from the start – we can do anything – and it was good to have the freedom about what we do with our music”.

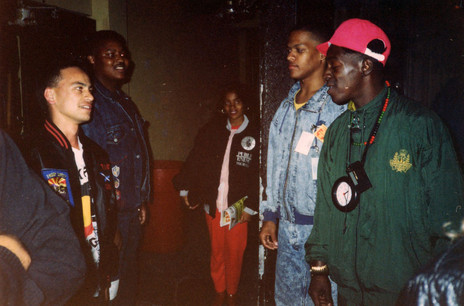

In 1990 the band was invited to Detroit by Rasul Muhammad, a son of Elijah Muhammad, the founder of the Nation of Islam.

In 1990 the band was invited to Detroit by Rasul Muhammad, a son of Elijah Muhammad, the founder of the Nation of Islam. Elijah Muhammad, who died in 1975, had mentored Malcolm X and Louis Farrakhan, both of whom had been an inspiration to the members of UHP. Te Kupu: “On the night of our performance in Detroit we met Louis Farrakhan twice, [the then] current head of the Nation of Islam. The second time we shared a light meal together. We later used excerpts from one of his speeches as a sample within one of our songs, ‘Whakakotahi’.”

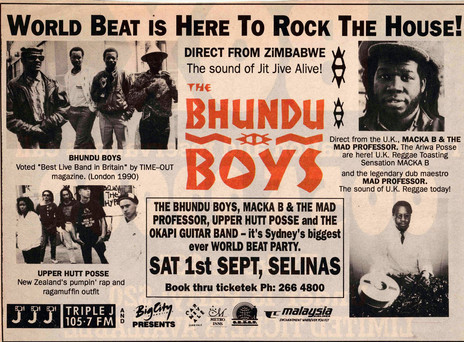

That same year, the band supported Public Enemy when they toured Aotearoa, and in Australia, performed with the British ragga artist Macca B and the Zimbabwean group the Bhundu Boys. They also received some notoriety after an incident with Samoan audience members heckling them at a gig at the Gluepot. The New Zealand Truth reported it as a “racial punch up” which was inaccurate. The Auckland Star also made false claims that UHP had stopped two Pākehā students from entering one of their shows, which was ridiculous given they were nowhere near the door. The band successfully sued the newspaper for defamation and won an out-of-court settlement, but it took four years.

Te Kupu was relatively philosophical about the matter, comparing it to the experiences of black American activists like Malcolm X and Louis Farrakhan: “If you’ve got something to say then the media is going to get on your case. It didn’t bother me that much, but all that had an impact on the band, there ain’t no doubt.”

Southside label owner Murray Cammick recalls, “I failed to take up the option for a second album within the period specified by the contract, so they were free to go elsewhere. This was prior to their visit to the US, so they thought it best that they make the trip unencumbered. Their next single [Ragga Girl] was released by the Tangata label.”

By the end of 1992, DLT, and MC B-Ware (who had left in 1989) were no longer with the group, and Teremoana Rapley was in the process becoming a backup singer for Moana and the Moahunters.

In 1995 UHP released its second album, Movement in Demand, through their newly formed production company/label Kia Kaha Productions, via Tangata Records. It has live instrumentation rather than programmed beats, and a noticeably slick level of production. The core of that line-up was D Word (vocals/keyboards) & his brother MC Wiya (vocals), Kiki Marama (guitar), Taki Matete (bass), and Earl Robertson (drums). The album cover features historical Māori leaders, which flows on from the themes in ‘E Tū’. This album had strong political content also, evident in titles such as ‘Whakakotahi’, ‘Wise Up’, ‘Gun in My Hand’, ‘Fuck the Status Quo’, and ‘Movement in Demand’.

Stephen Zepke said of Movement in Demand: “The lyrics, as uncompromising and uplifting as ever, send an astute message of anger, action, and education. The Posse are “Droppin’ bombs on the wicked deed” (‘Can’t Get Away’), but they’re “warriors of knowledge” as well. Dean Hapeta and the UHP have an uncanny ability to combine anger and aggression, with knowledge and love, and this is what makes both their music and their politics so appealing.” The album’s insert includes educational blurbs on each of the Māori leaders pictured on the cover. The music incorporates taonga puoro instrumentation (including purerehua and nguru), and one track is fully in te reo Māori.

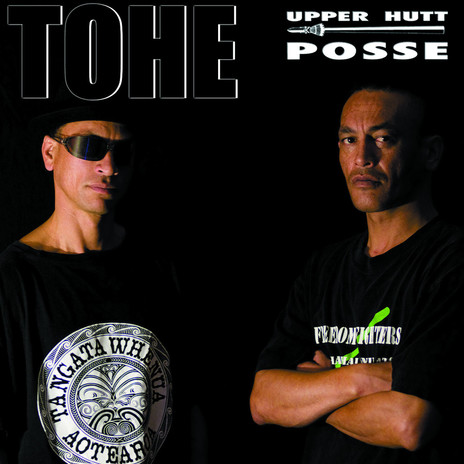

In 1996 Te Kupu decided to further commit to learning te reo Māori and enrolled at Te Wānanga o Raukawa (the first modern wānanga/Māori university, at Ōtaki). The fruits of his efforts can be heard on later album releases such as Mā Te Wā (2000), Te Reo Māori Remixes (2002), and Legacy, a 2CD album released in 2005 on Kia Kaha that features mostly English language tracks on one disc, Ngāti, while the other, Huia, is all in te reo Māori.

Tohe, from 2010 on Kia Kaha, continues this emphasis. It is a dubstep/drum & bass styled album of 10 tracks, mostly in te reo Māori. Graham Reid gave it a positive review on his Elsewhere blog but said, “Being largely in te reo (Māori) might put this beyond the reach of some, but as mentioned previously when writing about Hapeta/Posse that is rarely a problem: the urgency of Te Kupu’s delivery and the way he references significant events/figures/beliefs/Māori politics means there is more familiarity than many would think.”

It is an indictment of Aotearoa’s music industry and our society as a whole that music in te reo Māori does not generally get noticed or played, which is no doubt what Reid was meaning. But to produce te reo Māori music is a political act in itself, which fits Te Kupu and Upper Hutt Posse’s kaupapa of mana motuhake.

To produce te reo Māori music is a political act in itself, which fits Te Kupu and Posse’s kaupapa of mana motuhake.

The band’s reggae roots are still present on Tohe and can be seen in some of the imagery in songs such as ‘Haramai te toki’: “Haramai te toki – We go a chase them out of town ... Haramai te toki – This riddim a go chant them down”. Tohe is also more of a whānau affair, with the addition of vocals by Te Kupu’s daughter Ātaahua, and lyrics for ‘Hineahuone’ by his sister Kirsten Hapeta.

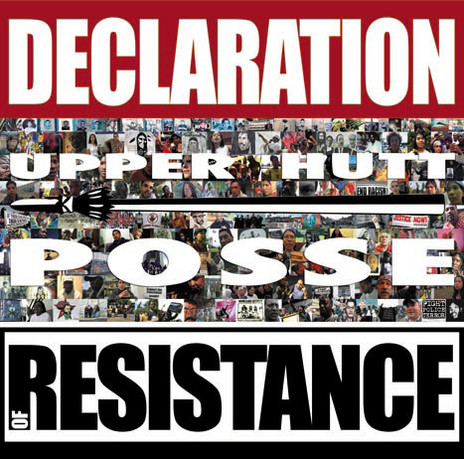

In 2011 UHP released Declaration of Resistance on Kia Kaha. It initially offers quite a departure with the first track, ‘Know’, in which Te Kupu is singing in more of a pop/R&B style, but then the album morphs into a stylistically diverse offering, including reggae and hip-hop. Reviewer Simon Sweetman wrote: “Declaration of Resistance has this retooled version of the band showing its skills not only as a force to be reckoned with as New Zealand’s oldest, most thought-provoking hip hop combo, but are also (now) one of our sharpest reggae bands. I love that Upper Hutt Posse’s sound keeps moving, keeps searching, keeps listeners surprised”.

Upper Hutt Posse is not showing any sign of letting up after their 30-plus years in existence. The group continues to evolve, push ahead and light the way for hip hop and reggae music in Aotearoa.

--

In October 2018 Upper Hutt Posse was inducted into the New Zealand Music Hall of Fame. The Hutt News quoted Dean Hapeta/Te Kupu saying he welcomed the “esteemed accolade” because it “accords with the appreciation and respect shown us all along by grassroots hip hop heads and lovers of conscious music.”

Te Kupu added, “In today’s increasingly interconnected world where environmental degradation, war profiteering, misogyny, police brutality and white privilege can no longer be denied I see our being recognised as according also with progressive activism over the last decade.”