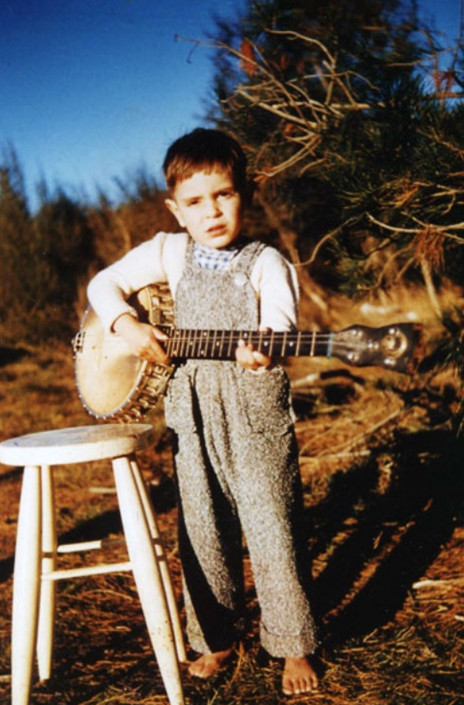

Brown grew up in a number of central North Island towns, leaving New Zealand for a time as a youngster to live in Canada after his father died. When he returned in his late teens, writing and performing music had become a passion.

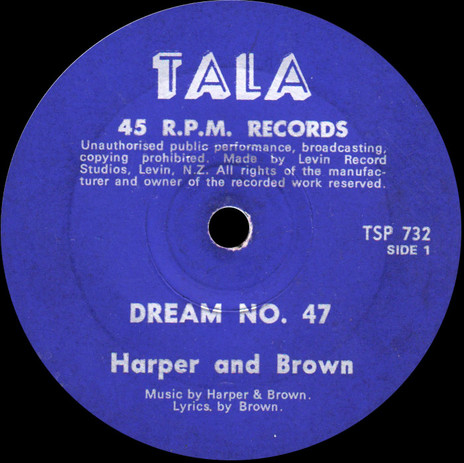

Brown was half of the duo Harper & Brown, played clubs with fellow songwriter Reece Kirk, and was in demand as a solo act. His first recording was with Harper & Brown for the single 'Dream No.47' b/w 'Sermon (In Rememberance of the Nameless)' recorded for Tala Records in a studio above an electronics shop in Levin, and released in 1972. Rob Harper played bass, fiddle and harmonies and Brown sang and let rip on his guitar and wah-wah pedal, which he’d recently acquired.

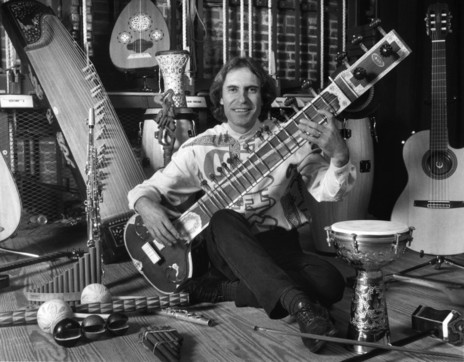

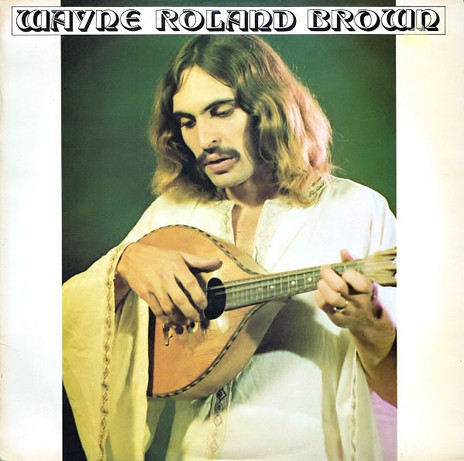

Brown was always keen to experiment and learn different instruments, adding a sitar to his performances early on.

While studying law at Victoria University he began to do pub gigs around Wellington with fellow songwriter Reece Kirk. One day Edd Morris from Strange Records turned up, and being suitably impressed he booked time at EMI studios. Brown worked with sound engineer Michael Grafton-Green, who’d recently arrived from Abbey Road Studios in London along with a new 8-track tape machine and desk. They managed to record, mix and complete the master acetate for what became Wayne Roland Brown’s first album in six hours. It included originals, Joni Mitchell’s ‘Woodstock’ and two versions of Dylan’s ‘All Along the Watchtower’, one an eerie rendition with Brown playing church organ and the other a sparser take. “I used to open and close my concerts with that song so I did the same on the album. Everyone was stoned in those days so I guess it was just part of the deal,” he says.

Brown was always keen to experiment and learn different instruments, adding a sitar to his performances early on. His philosophy was that if nobody told him he couldn’t do it, he’d just give it a go. Sometimes the result was embarrassing, but mostly, he says it worked.

Signed to Pye, his contract was taken up by RCA when Pye wound down its activities in New Zealand in 1975. Brown repackaged his first two recordings as the double album Chairs, Shoes And Songs Of Comfort and began selling them at his gigs.

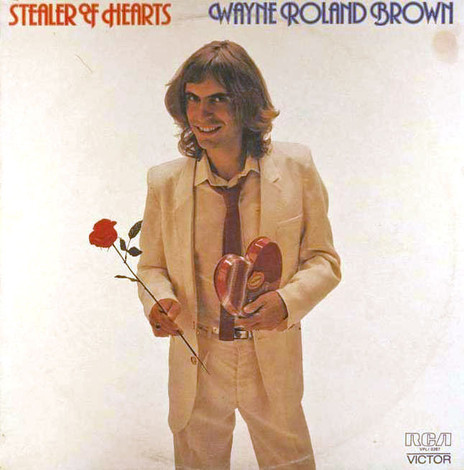

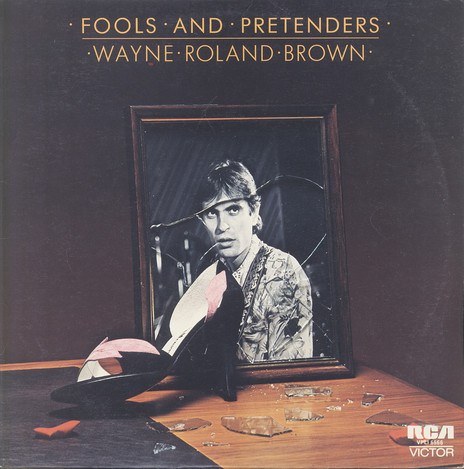

Contracted to RCA for two more albums, the songwriter continued to explore different styles. The albums Stealer Of Hearts and Fools And Pretenders were released in New Zealand and Australia in time for his move across the ditch. He picked up work in pubs, clubs and strip joints – “whatever kept bread on the table and the rent paid” – and was the opening act for Brian Cadd, Billy Thorpe & the Aztecs and other top Australian artists.

His folksy, storytelling style and diversity on so many instruments endeared him to the Australian Arts Council, opening the doors for a relationship that would last 25 years.

“They’d put me on a plane with a pilot, 18 to 20 musical instruments and a small sound system and we’d fly to remote communities and schools, including the opal towns.”

Being stranded by torrential rain at Lightning Ridge in the outback of northwestern New South Wales was a life changing experience. “I got to know the miners, drank beer with them at the pub and bowling club and listened to their stories. One of them gave me a rough opal, which I took back to Sydney. After having it cut I made a lot of money.” Brown was hooked and began making regular trips back to Lightning Ridge, investing in opal and gemstone mining.

If his albums weren’t selling in the record stores he was certainly making up for that at live venues, always making enough to pay for the next recording venture. Then his career got a real boost when one of his songs caught the attention of a country music star Crystal Gayle. The track ‘Our Love Is On The Faultline’ from his Fools And Pretenders album, written by his New Zealand friend Reece Kirk, became a No.1 hit for Gayle on the US Billboard Hot Country Singles chart.

Soon after that he went to Nashville and was signed to Herb Alpert and Jerry Moss’s Rondor Music. When he got a telegram from the publishing company informing him his song ‘True Love’ had been accepted by Seals & Crofts he thought he might be on a roll.

“It was a great version but then they had some management issues and it was dropped. As I learned in the music industry things can change very quickly. While six other artists covered the song, Seals & Crofts could have made it huge.” He renamed the track ‘Romancing’ and included it on his Flight Of Fancy album.

Another near miss came with the song ‘Essential Sensual’ used in the movie Cocktail, which starred Tom Cruise as a performing bartender. While viewers got to hear more of Wayne Roland Brown’s composition than any other song, it never made it to the soundtrack CD.

“There was a problem with my management in the US and the owners of the copyright would not negotiate a percentage. In the end I actually made more money from the movie than The Beach Boys did out of their song ‘Kokomo’, which was on the soundtrack.”

The album sold over 8 million copies worldwide and could have been another career changer for the New Zealand songwriter, who remains philosophical. “It’s called the music ‘business’ for a reason.”

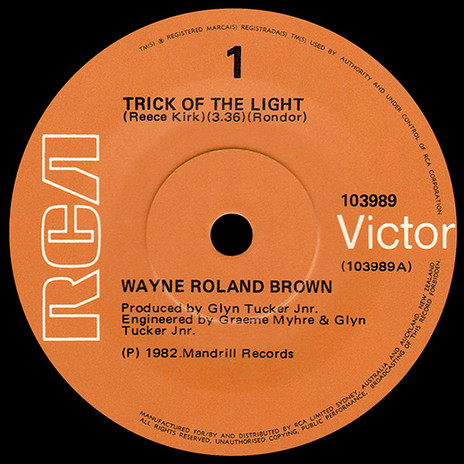

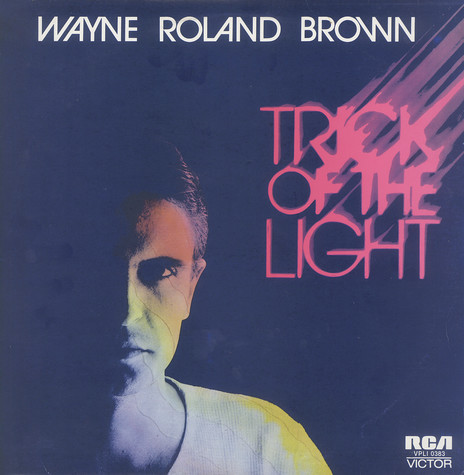

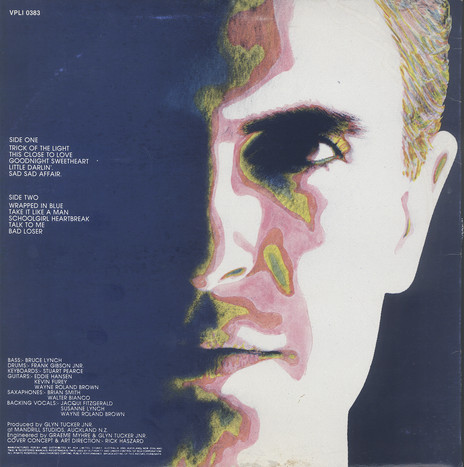

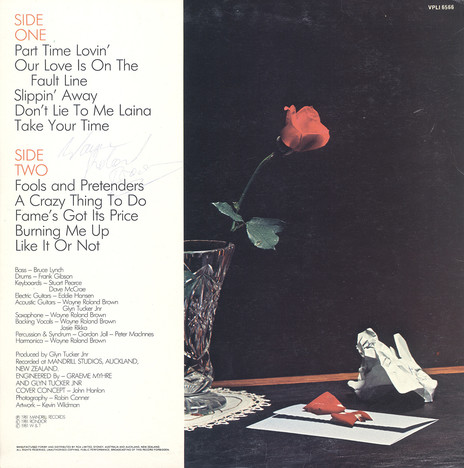

In 1982 Wayne Roland Brown returned to New Zealand to record Trick of the Light at Glyn Tucker’s Mandrill Studios. The polished pop songs were either Reece Kirk originals or collaborations, designed with radio play in mind. His rhythm section featured Frank Gibson Jr on drums and Bruce Lynch as bass player and arranger.

With the 1980s dance craze and the focus on extended mixes, Brown did a little genre bending with his song ‘Let It Burn’, which looked for a time like it might gain serious chart action. It was spinning on DJ turntables at nightclubs around Australia and the US, but industry infighting soon put paid to that.

“It was released on the Powderworks label through RCA in Australia, which invested a huge amount of money in a video but then there was a fallout between the A&R guys about who was going to get the credit and I got caught in the middle.” The video was never released.

Around this time Brown was experimenting with gospel sounds, which took him back to his roots.

Around this time Brown was experimenting with gospel sounds, which took him back to his roots. He’d come from quite a religious family, his father had been a pastor, and it seemed a natural thing to do. He was contracted by an Australian gospel recording company and while relatively pleased with the sessions it is not an album he recalls with any satisfaction. “They never paid me, the bastards.”

His follow up album Flight of Fancy was a compilation of previously recorded but unreleased material, including the first outing for ‘Essential Sensual’, six years after the movie Cocktail. Many of the songs were recorded in Nashville with multi-platinum award winning producer Bill Halverson.

Brown continued to explore the gospel roots of popular music on the songs ‘Free at Last’ and ‘I Believe’. For a sense of authenticity, he called on the Nashville Episcopalian Choir. “This wonderful wailing black southern Baptist choir turned up in two buses; there were 26 of them and 24 had personal managers.”

They all squeezed into Ronnie Milsap’s studio, formerly owned by Roy Orbison, who recorded most of his hits there. “The singing was one most memorable sessions I’ve ever done.”

The 1996 album Capricorn is a more laid back, tropical affair, celebrating 20 years in Queensland. Brown played many of the instruments himself to achieve a cruisy Cuban flavour. The sessions featured top US players: Jim Horn from the Hollywood Horns, guitarist Larry Chaney and bass player Dave Pomeroy.

In One World, which was recorded over 10 days at his Nashville home, he returned to the roots he’d been exploring progressively over three decades, mixing it up across multicultural musical boundaries. “I was touring schools, introducing kids to world music to hopefully spark an interest in the different ways of hearing music of the world to bring some cultural understanding.”

Brown says he continues to collect instruments from around the world. “I can’t help myself. I just sit down with street musicians and learn about what they’re playing.” His favourites are two Arabic ouds (“Their influence on western music has been huge with all the quarter tones”) and he loves the sitar and the sarod from India because, “You have to rewire your brain to play them and listen to them.”

On the Songs For All Seasons CD, he goes even further on the track ‘Meditation’, exploring throat singing, Tibetan prayer gongs, and mixing in Gregorian prayer chants, church bells, didgeridoos and clap sticks.

“I think they’re all trying to achieve the same place of meditation and contemplation and they just happen to be instruments from different cultural backgrounds. I like finding a commonality between seemingly disparate things and perhaps weaving them together into a new fabric.”

Having experimented with the sounds of the world on several projects, Brown began to reflect again on his involvement with the people of Lightning Ridge. His time as an opal miner, polisher and cutter, and the generosity of several legendary characters from Lightning Ridge enabled him to set up his own business, Gondwanaland Opals.

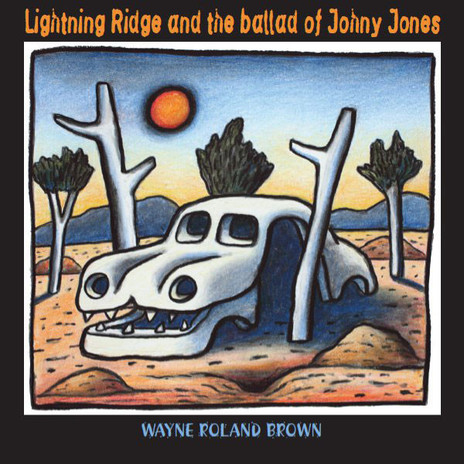

On his album, Lightning Ridge And The Ballad Of Johny Jones he delivers his own brand of country flavoured folk songs, celebrating the rare and precious Australian gem and life in the opal fields.

He wanted to produce an album the locals would listen to and thought it would help if it was about them. The title track, 'Ballad of Johny Jones', is the true story of the miner who took him under his wing. Jones, a short, strong man, had got himself into trouble with the police as a teenager and went on the run, joining Jimmy Sharman’s crew of boxers. Sharman would put up a tent outside pubs in remote townships, starting in the early 1900s, and challenge anyone to knock down one of his boxers in three rounds “to win a hundred quid”. Johnny Jones became one of those boxers until he couldn’t take it anymore. He became an enforcer on the Melbourne wharves and after getting into trouble headed to Queenstown to the Quilpy opal fields.

“A lot of the people who go to the opal fields are escaping something, but within four years he’d made a lot of money,” says Brown. When he retired a few years back he and his wife set up a karaoke business and asked Brown to write a song they could use in karaoke bars.

Wayne Roland Brown says the opal business is like the music business. “For everyone that makes it there are many who don’t. It’s a hard life and I’m attracted to it and still go there a month or two a year and some of the miners still come and visit me in the US.”

So what has he learned from this diverse musical journey and how has it changed him? “When I was younger I guess I wanted to be independent, make music, meet girls, travel, learn about different kinds of music and eat great food. That hasn’t changed much.”

What has stuck with him is how similar human musical expression is, regardless of culture. “We’re all looking for another language to express ourselves and music is that other place of being. There’s never been a culture that hasn’t got some kind of music.”