Castelow hails from the small, south Canterbury satellite town of Ashburton and, like most rural communities, music was not a big focus for most of the town’s populace.

“Ashburton was, and probably still is, a very sport heavy town,” he says. “The kings of the town were the rugby players – definitely not an artsy, music enthused kid who was in musicals and starting a band. We used to hire a local hall and put on underage concerts with a couple of bands. Everyone would preload and come along even if they didn't like music – it was something to do on a Saturday night.”

Even though he wasn’t residing in a cultural hotbed, Castelow was lucky enough to have an older brother who kept him abreast of what was happening in the music world, in what was an extremely important time for guitar bands.

“My older brother Tim was always a huge influence on me as a kid. He would make me tapes and send them to me from university in Dunedin. One of them had Weezer’s ‘Blue Album’ on one side and the first Foo Fighters album on the other. Big tape for a small boy.”

After high school Castelow moved north and enrolled in the Christchurch Jazz School. He was also active on the rock music scene at this time with his high school band, Android, who were playing headline spots at the Dux and networking with other bands, including Clowndog, Orkid and Slipstream. When the group’s bass player left Castelow found that a replacement was easier to find than he perhaps initially thought it would be.

“I’d had been banging around with a tall, lamb-chopped hunk called Dean Cameron. There was a flat in Riccarton that we had been hanging around and we’d jam on tunes by Tom Petty, Pink Floyd, Smashing Pumpkins – anything that someone knew. He could play some cowboy chords on the acoustic but he was no thunder fingers on the bass … yet. It was my school friend Stefan Cook that suggested Dean play in Android and that I should teach him the bass. We put some Twink on the fretboard and taught him the songs.”

Next the drummer left and again Stefan suggested Chris Spark, who was also kicking around and attending jazz school.

“I’d known him for a few years as our high school bands would do these rural hall shows and make money for recording and gear. We thought that we would just rename the band and write new stuff. It didn't take too long before we had a set ready and we were playing every other weekend and anywhere that we could.”

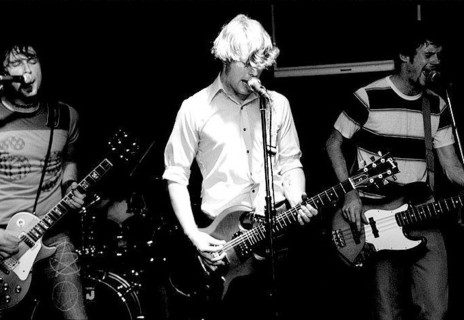

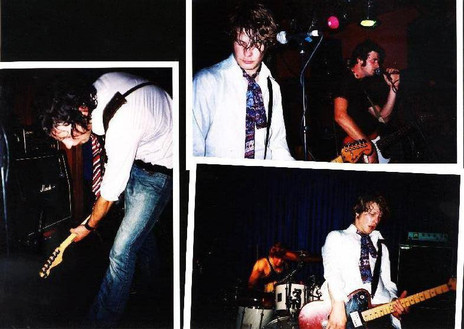

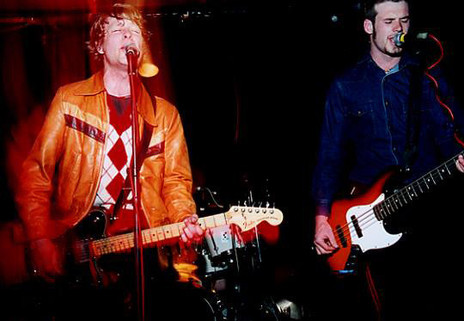

So in 1999 degrees.k was born. Rather than fading into the plethora of alt guitar bands in the garden city at that time, they carved out a niche for themselves as being a stylistically diverse band, embracing both the noisy guitar squall of groups like Fugazi and early Shihad as well as the melodic inclinations of artists like Jeff Buckley and The Pixies.

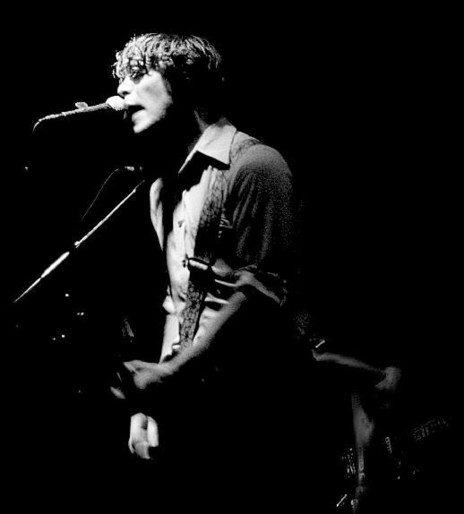

The group was also distinct in that Castelow possessed a very strong, keening voice that was equally at home soaring over the top of buzzsaw guitars as it was on the tenderest of ballads.

“I’ve always sung since I was a kid – primary school competitions, musicals, choirs and all that. It's something that I've just been doing before any kind of realisation. I think through having a voice it has informed my writing of loud songs. I guess if a singer can get over the top of a noisy band and push it along, it encourages the instruments to play louder or harder.”

Around this time degrees.k caught the attention of mix engineer, arbiter of quality Christchurch guitar groups and Failsafe Records founder Rob Mayes. Mayes worked for a local sound company and had access to some space and gear, affording the band their first opportunity to record some material.

Castelow admits that the band were green about the recording process at that point and says Mayes was very helpful and full of advice.

“Rob was doing sound at the Dux De Lux one night when we opened for some band,” recalls Castelow. “He was immediately interested in recording us and asked us if we had anything in the pipes and would we be keen to talk. I'm not sure he had checked it out with the sound company that he worked for, but when they were all up at The Gathering that year, running cables and flying speakers over the new year period, we were in their warehouse knocking out our first recordings and trying to get a massive drum sound.”

By the time the band released their debut album in 2002 they had notched up several tours of the country.

Degrees.k recorded “about 18 songs” which resulted in their two EPs and subsequent debut album. “We overdubbed in his home studio above Death by Chocolate on Oxford Terrace over the course of a year or so and put out the material as it was ready. The EPs [Jay.Tea.Four.Pea and Click] were both just limited edition CDR runs whereas the album [Lifelike] was pressed properly – about 500 copies. To my knowledge these are all sold out. He [Mayes] was always very supportive of the band and just really wanted to make those records for us. I’d not really been in front of a mic in a studio environment much before so his input was great when it came to singing and getting guitar tones.”

The EP Jay.Tea.Four.Pea spawned the band’s first successful single in the form of the equally epic and aurally eviscerating ‘John Travolta On My Shoulder’. The song received airplay on Channel Z and across student radio stations. By the time the band released their debut album in 2002 they had notched up several tours of the country. Around this time it also become apparent that all the guitar overdubs on Lifelike would be impossible to recreate live with just one guitar. Enter Ben Edwards.

“I went to town on the guitars [while recording Lifelike] so we needed another guitarist,” recalls Castelow. “Ben Edwards was playing in his band Skeeter as well as playing bass in Slipstream and we just felt like he had the right vibe. We asked if he wanted to join and he was into it.”

The trend among New Zealand guitar bands at that time was to move over the ditch to Melbourne, a move that Shihad had successfully pulled off but one that stalled the likes of Fur Patrol and Pan Am when they had attempted to set up shop there. Degrees.k bucked the trend somewhat when they set their collective sights on Sydney. After relocating the band busily set about networking and establishing themselves in a new city at a time before things like social media and Bandcamp existed.

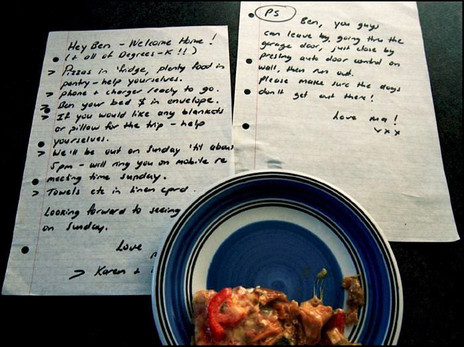

“We all wanted to get out of Christchurch and test the waters. We decided on Sydney because at that time every NZ band was moving to Melbourne. When Ben Edwards joined the band, just as we released Lifelike, he was a big motivator and would say things like ‘no stone un-turned’ and ‘punch punch’. He was more internet savvy than any of us, these were the early days of Hotmail and Myspace and he really grew our presence in that field.”

Degrees.k tried to hit the ground running, burning a bunch of CDs to hand out to whoever would listen. “We got a rehearsal space, started getting drunk at the ‘Townie’ [Newtown Town Hall] with the local indie yobs and getting gigs,” says Castelow.

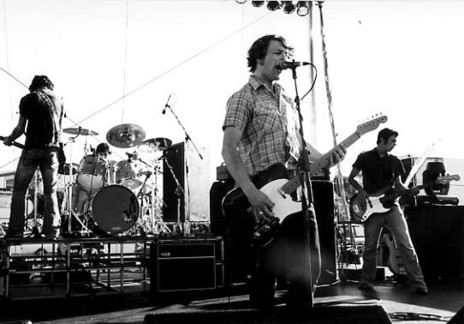

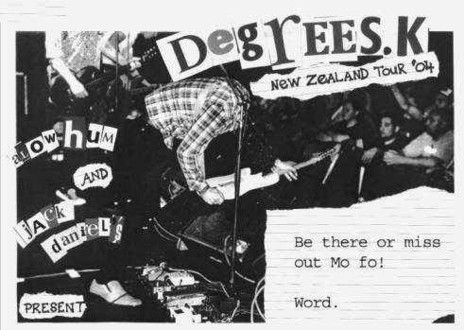

Their live show began to attract attention as the band gigged constantly in both Sydney and Melbourne. “We drove up and down the Hume Highway a lot between 2003 and 2006,” says Castelow, “we’d do weekends in Melbourne and be back for work on Monday. We got picked up by Aloha management and they started putting a few ducks in a row for us.”

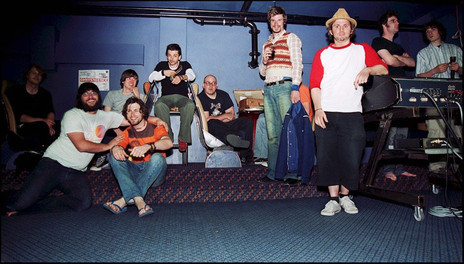

The band spent a week in a Melbourne studio with producer Lindsay Gravina, who had worked with The Living End, Jet, Spiderbait and other notable Australian rock groups. The recordings became the Children Of The Night Sky EP.

“I’d say this period was a high point for us,” says Castelow. “We were in a fantastic studio and had it for a whole week. Lindsay was generally a night owl so we would start in earnest from about 4pm and go through until morning. And he was also as blunt as fuck. If he thought something sucked or he didn’t get it, he’d really give it to you to make you go harder.”

Even though they were now based in Australia, regular trips back to New Zealand were a frequent occurrence. The band flew over to play on one of Ian “Blink” Jorgensen’s early A Low Hum tours and played to packed houses at venues such as the Kings Arms in Auckland. The four piece line-up meant that they sounded just as huge live as they did on record and Eddie Castelow was a high-energy frontman who loved to get down in amongst the crowd if the mood took him.

Fast forward to 2006: after three years of toiling away in Australia the cracks began to show and some members of the band were longing to return home. Chris Spark was the first to jump ship, closely followed by Ben Edwards.

“I’d say a low point would be when not one, but two members decided that they wanted to head home,” says Castelow. “One we could handle. Chris Spark was already on a journey to a higher power and was very religious, which always made for great conversations and ribbing in the van, so when we started to get momentum and do all the things that a band gets involved in, like partying, being away from loved ones etc, he decided to head back to NZ.”

Armed with a new name for his next musical project – Dictaphone Blues – he started writing and recording material for what would be the debut album.

“We had just toured NZ with Ejector and knew that Oscar Wuts was looking for a change of scene and to move out of Wellington. He was on board to fill Chris’s spot which we were over the moon about. The weekend that Oscar was visiting us in Sydney and trying it all out, Ben decided to tell us that he had to go back to Christchurch to complete his teaching degree, something which we hadn't really heard anything about the whole time he had been in the band. We were totally shocked and thought that he was having a meltdown that we could sort through.”

Castelow soon followed suit and moved back to New Zealand in 2006 to pursue a long-term relationship. This was a difficult decision by all accounts as, even though the line-up changes had been traumatic, the new version of the group was writing and recording in earnest and with good results.

“We had been working hard on new songs for a few months and we had been demoing them in the practice room with good results and I’d say that they were the best songs that we had ever done for sure. Dean was quite hurt and our next few months were very rocky. It made me look at myself a lot; how I acted in a band and how I treated those I played with. Everyone gives up other things to be in a band and I needed to be reminded of that.”

Upon arrival back in New Zealand, Castelow made Auckland his home base. Armed with a new name for his next musical project – Dictaphone Blues – he started writing and recording material for what would be the debut album. He could be spotted playing solo shows around Auckland at this time, usually with just an acoustic guitar and an iPod full of backing tracks.

However, he wasn’t in a happy place. “The music became either really negative, aggressive electro or forlorn balladry,” he recalls.

Castelow initially moved into a Kingsland flat that was well known amongst the local musical community as the headquarters for Lil Chief Records, an indie label run by Jonathan Bree and home to acts such as Princess Chelsea, The Tokey Tones and The Brunettes. It wasn’t too long before he was enlisted to play in Lil Chief groups – namely drums for The Ruby Suns and then guitar for The Brunettes.

“We [The Brunettes] took off for four months around the UK, Europe and some USA in there too. This was the longest tour I had been on and there were six of us in the band with a tour manager so things could get pretty claustrophobic and inevitably things got heated at points. I was enjoying the finer things that Europe had to offer – things that I couldn't get at home (namely hash) and not everyone was into that. I wrote a lot in the van and we watched a lot of Hitchcock.”

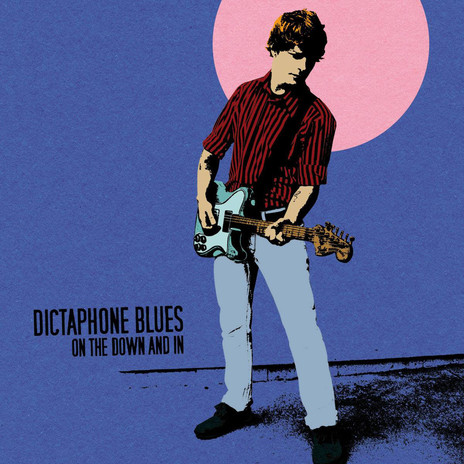

When he returned to Auckland he had the first draft of what would become the On The Down And In album ready to go so it made sense that he would need to find a band to perform the songs live. At the same time, another ex-Christchurch group, Heavy Jones Trio found themselves in limbo when their singer, Kelly Horgan, quit the group and headed back down south. Eddie knew the band from their time on the scene in Christchurch together and although they had never made music with each other they were pals and shared a fondness for Fender guitars, dandy outfits and chiming power pop tunes.

Some of the newly formed group’s first shows were supporting Liam Finn on his very successful I’ll Be Lightning album tour around New Zealand. The band line-up settled around this time and comprised Myles Allpress on drums and vocals, Rob Collins on bass and myself, Ben Eldridge on keyboard and guitar. Around 2009 I departed the group and the band continued on as a trio before adding Matthias Jordan (ex Pluto) on keys and vocals and in 2014 Rob Collins was replaced by Barney Chunn on bass. Nowadays the group is managed by Reuben Bonner and is signed to his record label, Banished from the Universe.

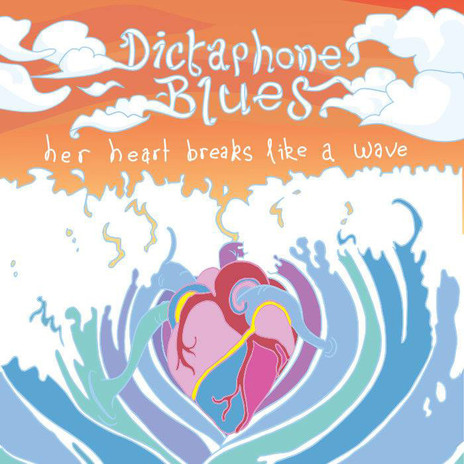

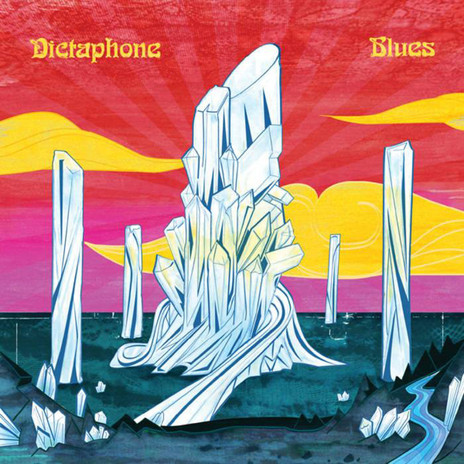

Castelow has released three albums under the Dictaphone Blues banner now – On The Down And In, Beneath The Crystal Palace and most recently, the well-received Mufti Day. His writing and recording process in Dictaphone Blues tends to be non-collaborative, with Castelow more often than not having the group learn the arrangement via the fully recorded song.

“Each album has been different and that has been intended. It's cool to have a project that isn't defined by a strict way of doing things. I'm very lucky that I work with loose units that don't mind me taking the reins and delivering them with finished songs.”

He also moonlights as a drummer with Auckland garage popsters The Conjurors and has played bass with Anthonie Tonnon.

Castelow has also turned his hand to recording and producing bands and artists in his own studio. Located in the same building as the iconic The Lab studios in Mt Eden, Castelow describes his studio space as “... a modest set up of 8-track 1/2 inch tape, 16-track digital, a few outboard pre’s, some cool mics, lots of vibe and an enthusiastic guy leaping around.”

–

In February 2021, Edward Castelow released Mirth, the first album under his own name.