AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

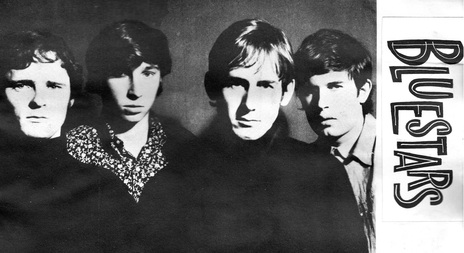

The Bluestars

As the angry young man in the lyrics rages at the world around him – “it’s not my fault I don’t belong, it’s the world around me that’s gone all wrong” – it’s as much an anguished cry for acceptance as an uncompromising statement of being. You made me, so if you don’t like me you’ll have to change, not me, he seems to scream as the song howls its way to its fuzz-strewn conclusion and a final, biting “I’m a social end product, so don’t blame me.”

The naive emotion of the song has weathered well over the decades and garnered cover versions from American, Dutch and NZ bands, and is regarded as a garage punk classic by many fans of the genre. But who were The Bluestars, composers of New Zealand’s very own ‘My Generation’?

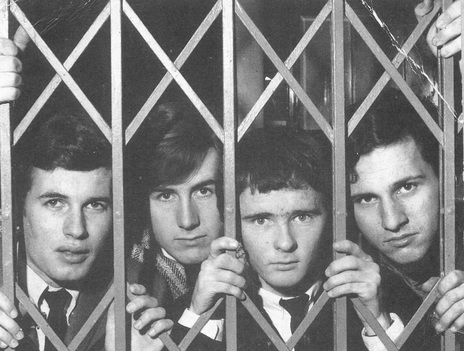

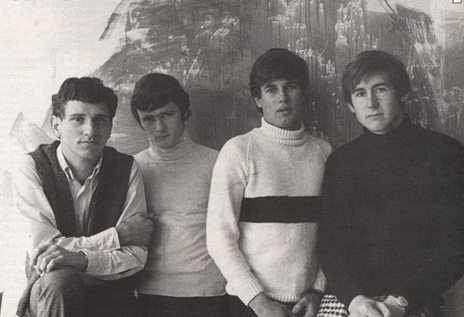

The Bluestars – also worded as The Blue Stars on their Decca releases – were a social end product of the inner suburbs of a rapidly growing early 1960s Auckland, New Zealand’s largest city. The band was educated in the North Island city’s bastion of conservative education, Auckland Grammar, around the nucleus of fourth former Murray Savidan and his school buddy, Roger McClay. They called themselves The Nomads and cobbled together a set of rock and roll standards, which the embryonic outfit saw fit to unleash at Grammar’s end of year concert, much to the disgust of long time principal W.H (Henry) Cooper.

Murray Savidan remembers; “We came off the stage and assistant head Jock Bracewell came up and said ‘Good work boys’, but Cooper went right past us into his office. He’d tried to stop us from playing, but for some reason he gave way.”

The Nomads steadily chomped their way through a number of drummers, a tea chest bassist and one John Hughes, their school performance pianist.

Savidan: “We were cottoning on to the idea that Cliff Richard and the Shadows were pretty cool, and of course they didn’t have a pianist so ffftt, out went John. Ahh, the callousness of youth.”

John Harris joined on drums after a chance meeting with Murray and Roger at Harmony House, the Auckland second hand store.

Out of the confusion of passing band members emerged the line-up which would constitute The Bluestars. John Harris joined on drums after a chance meeting with Murray and Roger at Harmony House, the Auckland second hand store. After turning up at the first Nomads practice with a clarinet, Harris, an Auckland Star reporter, scratched together the makeshift drum kit he’d have to hide under his bed from his anti-band father between rehearsals.

Harris brought with him a friend from a rock and roll band they’d been messing around together in. Rick van Bokhoven was a graphic artist with a Parnell advertising agency and a talented singer with an ear for picking up songs.

One final line-up change; exit original Nomad Roger McClay, prompting a band reshuffle. Guitarist Savidan moved reluctantly to bass, Harris to lead guitar, van Bokhoven to rhythm guitar and after another round of musical drum stools, Jim Crowley, a clerk with the Union Steamship Company, joined on drums. New band, new name – The Bluestars – co-opted from a Shadows song.

Despite The Bluestars mastering Shadows dance steps, the instrumental rock of the day and getting a good stream of church and youth club dance engagements, a musical revolution was about to reveal itself to them – the first Beatles album. Like cool teens all over the western world, it stopped them in their tracks.

“We went to Murray’s place," says John Harris, "and he said, ‘listen to this’, and it was ‘Please Please Me’. We listened to it and we knew.”

Savidan, the most business minded of the band, promptly cancelled their next two month’s engagements and The Bluestars retired to their practice space – various family living rooms – and learned the entire record.

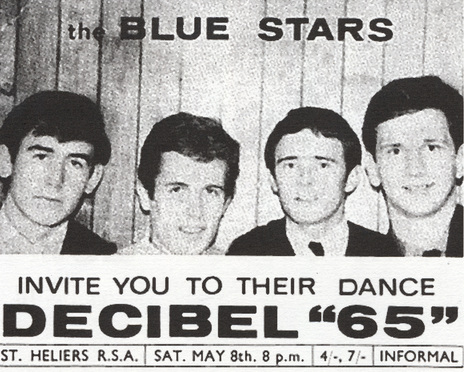

Debuting their new set at St Chad’s Hall in Epsom, they were met by only a small audience. The Bluestars shrugged it off, the songs felt good. Auckland would soon wake up.

The next week they were booked at St Vincent’s in Remuera. By then word had got out and the concert was sold out with several hundred dancegoers left outside on the footpath. Their instincts had not deceived them – the band was hot and their Beatles set hotter.

The bands left in the beat slipstream wondered what had hit them.

Savidan: “We weren’t the only band playing the suburbs by any means. One of the other groups was The Versatones with Roger Skinner (later of the Pleasers). They were good when it came to Shadows stuff, but we floored them.”

Harris: “They were made redundant overnight. Later we played a dance at the Tamaki Yacht Club with them, those poor guys were so immaculate technically, but they had no emotional connection with the audience. We came on playing as rough as guts, but it was an emotional connection, the kids wanted the music we were singing.”

No one could call The Bluestars simple beat copyists. They played a good 20 per cent band originals. When they finally came to record, it would be only band originals.

No one could call The Bluestars simple beat copyists. They played a good 20 per cent band originals. When they finally came to record, it would be only band originals.

Savidan: “Again it came back to The Beatles; they started to write their own music and that set the scene, so, ‘why don’t we write our own songs?’ ”

The mop tops' range of covers on the early Beatles albums – embracing Tamla Motown and American rhythm and blues – also reflected The Bluestars’ own diverse tastes and writing styles.

By 1964, The Bluestars were attempting to get a record out. Murray Savidan remembers a surreal demo session for Eldred Stebbing’s Zodiac Records at the studio in Saratoga Ave, Herne Bay.

“We arrived and he had a garage underneath. Stebbing had asked us to audition, so we got a couple of songs together and went down to Saratoga Ave where we were remote controlled. One guy popped into the studio for like, two minutes, to move a microphone in front of our drum kit. All our communication with Stebbing or whoever was in the room above was through the intercom. We didn’t see a soul. We put our numbers down and it was the classic ‘don’t call us, we’ll call you.’ ”

They went back to the suburban dance circuit, playing two to three times a week at five quid each a night, and venturing as far afield as Whangarei in the north and Rotorua in the south.

The band continued steering clear of the “seedy inner city clubs with their sweaty venues, long hours and poor pay.”

Under Savidan’s guidance they were organising their own dances, hiring halls like the Tamaki Yacht Club, playing to 300 kids at two and six a pop, biding their time. The Bluestars hadn’t abandoned thoughts of releasing a record after the weird experience at Stebbings.

So when sometime actor and voiceover man Terry Hayman pestered them to let him become the band’s recording manager, they agreed. What pricked up their ears and separated Hayman from the other opportunistic hustle merchants who’d wanted to manage The Bluestars was his claim that he had a contact at Decca Records in London.

Before they knew it, The Bluestars had managed something their heroes The Beatles couldn’t – they were signed to Decca on their first approach.

Dreaming big time, the band said “ask them if they’ll sign us". Before they knew it, The Bluestars had managed something their heroes The Beatles couldn’t – they were signed to Decca on their first approach. In a stroke they had become the first NZ band to score a debut record contract in Britain.

“They (Decca) were still pissed off at missing out on The Beatles, so they weren’t going to turn down anyone without at least listening to them first,” is Murray Savidan’s theory on the band’s startling good luck.

Jim Crowley went one better, he wrote a song about it, ‘Suppose We’re Away’. “Get up, get dressed, coz we’re on our way, good news this morning …” went the upbeat words.

High on the buzz, they headed for the studio. Hayman linked them up with a young NZBC engineer, Wahanui Wynyard. Another stroke of luck, as Wynyard was to become one of the country’s best recording engineers and a dab hand at a wild garage punk mix.

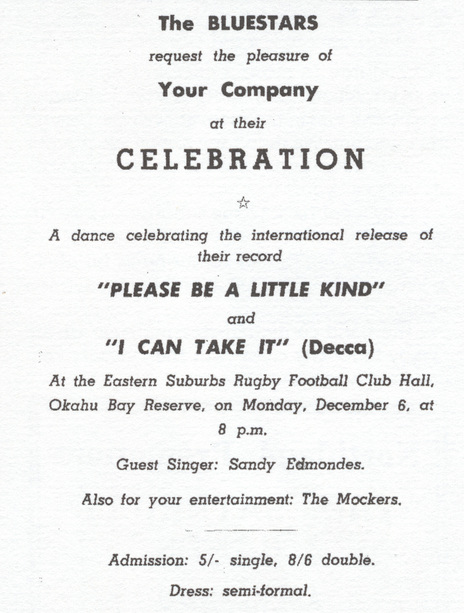

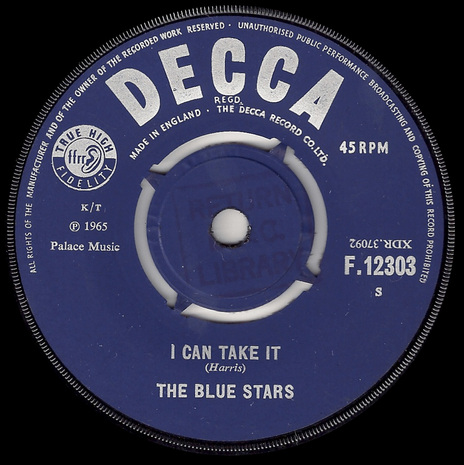

Early one Sunday morning, Wynyard and The Bluestars slipped into the Radio Theatre in Auckland’s Durham Lane and recorded four songs including ‘Please Be A Little Kind’, ‘I Can Take It’, ‘Just Fell In Love With You’ and ‘Baby Come Home’. The session was rushed, as the band had to steal away before midday when the symphony orchestra arrived. The tape was promptly dispatched to England. The result, a December 1965 release, coupling the ballad ‘Please Be A Little Kind’ and the fiery R&B of ‘I Can Take It’.

While it wasn’t a hit, the single was released in Australia, Japan and the USA, where Billboard reviewed it favourably.

In early 1966, ‘Please Be A Little Kind’ b/w ‘I Can Take It’ hit local record stores. The Bluestars celebrated in style with a record release concert at Tamaki Yacht Club, while the record climbed to No.12 on a local chart and gained them valuable radio airplay.

Around town, the band began to play bigger venues on the back of their new fame.

Around town, the band began to play bigger venues on the back of their new fame, pairing with hot locals such as The La De Da’s, Larry’s Rebels and The Gremlins.

One well-received concert at Matamata gave the band an insight into the dubious practices of local promoters. After the wild show, the promoter took the unusual step of paying the band on the night double what they thought they were going to get.

A mistake surely, protested Savidan. No, insisted the promoter, that’s what I agreed with the Auckland agent. On the journey home it finally clicked. Normally the fee would be paid straight to the agent, who would then extract his 20 per cent and pay the band. The agent had obviously asked for twice what he told the band they were getting. Not an uncommon practice, remembers Savidan.

Shady promoters aside, The Bluestars were looking ahead to their second single for Decca. Two tracks were recorded for the single at Mascot Studios – ‘It’s The End’ b/w ‘S’pose We’re Away’. It was a torrid recording session, typical of the day.

Savidan: “We didn’t have a chance to play around with sounds and experiment in the studio. We had no creative input from the producer, no George Martin, just learnt the songs and played them.”

Harris: “We’d be told we had three or four hours at the most to do four songs, once through with overdubs.”

So it seemed a luxury when they allowed themselves at least eight attempts at the sparse ‘Don’t Wanna Be Lonely Anymore’ at the same session. The song was just off being an epic, but at the time the band felt it was just not quite there.

The Bluestars answered the rejection in the best way possible – with ‘Social End Product’ becoming their enduring claim to fame.

To the band’s dismay, Decca rejected their second single. The Bluestars answered the rejection in the best way possible – with ‘Social End Product’ becoming their enduring claim to fame.

John Harris reflected on his September 1966 creation. “I don’t think I was a crazy young kid when I wrote it. I always had a conscience and this was an angry young man trying to make sense of things, and writing about them.”

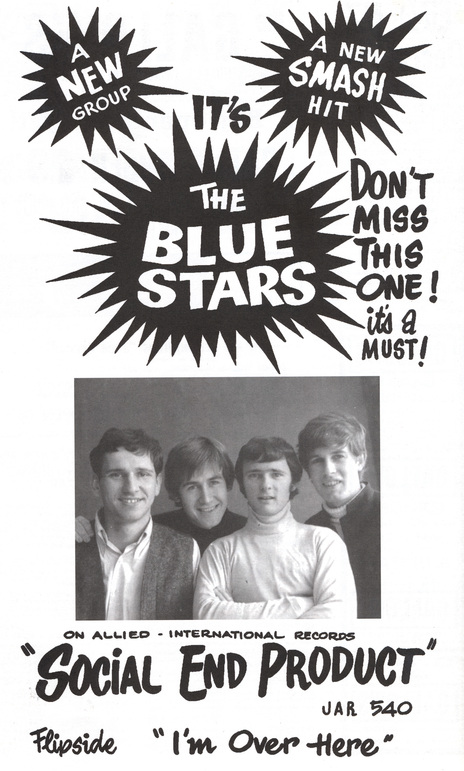

Inevitably with such a wild song, controversy wasn’t far behind. Allied International Records, which released many a great NZ disc in the 1960s, took exception to the opening line, “I don’t stand for the Queen”. It was a reference to Harris’ rebellious habit of sitting down during the opening anthem at the movies, when everyone was expected to stand. Allied insisted Queen be changed to cream. “Yeah sure,” said Harris, not altering a syllable.

The controversy made the local tabloid, adding to previous media hijinks when The Bluestars had a photo banned from NZ Woman’s Weekly because their band uniform made them look like Catholic priests.

Harris, in his capacity as an Auckland Star journalist, also found time to scrawl off a two-page spread on being in a pop band.

The Bluestars soon returned to Astor Studios in Nugent Street, where they’d recorded ‘Social End Product’, this time backing sometime American manager Tony Fernandez’s Hawaiian singers. Weird, but the money was good.

They were still venturing further a field with their music as well. John Harris remembers a Whangarei A&P Hall gig with Auckland’s The Dark Ages, promoted by the city’s funeral director, John Newberry.

The Bluestars, then immersed in the Beatles’ Revolver album, chopped out their crisp set to the sight of caged go-go dancers frugging furiously to the audience’s approval. The Dark Ages and their raw R&B had the opposite effect.

Harris: “They didn’t go down too well in redneck country. They slithered across the floor, had sex with the microphone – good clean lads.”

The crowd literally stopped in their tracks, jaws agape. Afterwards, it was back to the hotel to recover.

Harris: “We used to sweat our guts out. We were on stage from eight to one some evenings, with only five to ten-minute breaks. We’d get home covered in sweat, ears ringing all night, exhausted but elated.”

With two high profile singles behind them and strong local pulling power assured, The Bluestars decided to turn professional.

With two high profile singles behind them and strong local pulling power assured, The Bluestars decided to turn professional. All except Rick van Bokhoven, who decided that it wouldn’t be much fun. He continued to make intermittent appearances upfront. Jim Crowley too felt like a change and spurred on by the new prominence of organ-based groups such as The Small Faces and Spencer Davis Group, moved to organ. His replacement on drums was a 17-year-old from Howick, Eric Jackson.

Still wary of the inner city clubs, but in need of a regular gig to supplement their suburban dances, Murray Savidan hit on a typically independent minded solution – they’d start their own club.

Premises were soon found on Remuera Rd, next to the fire station above Fred’s Burger Bar. Fred, an ex-boxer, thought he was onto something here, with his percentage of the door take and the potential trade spin-off from hordes of hungry teens, especially as the club and burger bar had a connecting dumbwaiter. However, time would show Fred had bitten off more than he could chew.

The Bluestars named the club The Gallows and set about painting it (blue of course), while Savidan applied for the necessary permits and set the opening night for October 20, 1966.

Savidan: “We’d done a little post box campaign where we told local families what we were doing and how it was good for the area and how we’d be mindful of noise.

“What happened was, being on Remuera Rd, metres from some of the wealthiest families in Auckland, when we applied for the appropriate licence, it never came through. We kept ringing the council asking for the permit, but didn’t realise it was never going to come.”

So they went ahead anyway on the verbal say-so of a council officer. To combat the sound they left the venue’s windows closed during sets. This worked fine until Nobody’s Children omitted to do likewise during an engagement there.

Local current affairs programme Town and Around filmed The Bluestars in the venue punching out a fiery version of ‘Social End Product’.

This pleased neither the wealthy neighbours nor the firemen who lived next door. As one newspaper put it “Wealthy Remuera, it seems, just doesn’t swing.”

Complaints became commonplace, culminating in a summons for operating an illegal club. The Gallows closed and poor Fred ended up in court, where he was fined one pound and told to close the club down for good.

But not before local current affairs programme Town and Around filmed The Bluestars in the venue punching out a fiery version of ‘Social End Product’.

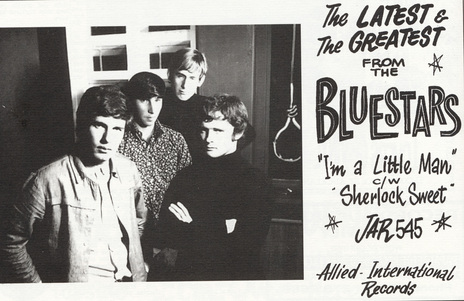

It was the beginning of the end for The Bluestars, despite pleading letters from Tony Fernandez begging them to join him in Sydney. They did one last tour around the beach resorts in January 1967, managed a final single for Allied International, ‘I’m A Little Man’ b/w ‘Sherlock Sweet’; the latter featuring another evil John Harris fuzz guitar break, then ground to a halt in February just when Allied International A&R man Fred Noad claimed they were coming into their own.

Within two weeks, Jim Crowley had moved to Sydney while Rick van Bokhoven carried on playing in bands around town and Murray Savidan continued with his growing passion for photography.

And John Harris, the angry young man of Social End Product? Perhaps it was inevitable that the passion of his words would find another outlet, but not in a rock band. The Bluestars were Harris’ one and only.

Harris: “It was more than a band for me, it was more like a marriage. We had the same cat-fights, arguments and sub-groups.”

Harris returned to music in the early 1970s as part of the St Paul’s Singers – an evangelical singing group – still playing his guitar and writing songs, only this time it seemed he’d found some peace. One of his compositions ‘Man of Glory’ became a well-known religious song and can be found on one of the many records released by the St Paul’s Singers in the 1970s.

John Harris is the founder and was for many years managing director of TV production house Greenstone.

Harris was named as the 2012 Screen Production and Development Association / Onfilm Industry Champion for services to the NZ screen industry.

John Harris - guitar, drums, vocals

Murray Savidan - bass, vocals

Rick van Bokhoven - guitar, vocals

Jim Crowley - drums

Eric Jackson - drums

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air