His circuitous route to life in New Zealand started with the discovery that his errant dad was born here. Disenchanted with life and the music scene in the big hair and lite metal environment of mid-80s America, moving to NZ was his way of dropping out and starting afresh.

“I was fed up with the scene,” he says. “It was the 80s, cocaine was at its peak in California, bad music was at its peak, and I was surrounded by people in the music industry who didn’t actually love music. I was so disheartened that I just said ‘forget it’. Combined with a broken heart and stuff. At the same time I found out my father was born in New Zealand but left as a child, and I decided to start my life over again. I had a year away from music, and came back to it with fresh ears.”

In New Zealand his professional life took a completely different turn, and he hooked up with a wide-ranging contingent of jazz, folk and improvising communities.

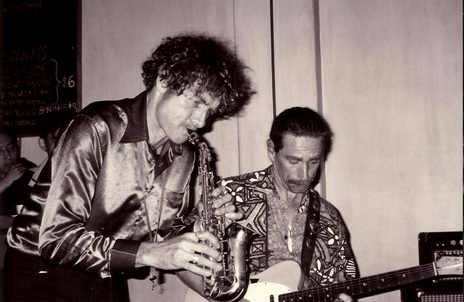

In America, Gavin had roadied for one of his favourite guitarists, jazz fusion player John Abercrombie, and by the mid-80s he was what he describes as “the widdly-widdly” guy, a “guitar hero” in a band called Relayer that at one time, got a single into the USA top 100.

In New Zealand his professional life took a completely different turn, and he hooked up with a wide-ranging contingent of jazz, folk and improvising communities, over the years performing and recording with the Nairobi Trio, the Jews Brothers, Lorina Harding, Whirimako Black, Tom Ludvigson, and many more.

While his skills as an accompanist inextricably lift any project he contributes to, the core of Gavin’s work can be found on the two Gitbox Rebellion albums, and his three solo albums.

Gitbox Rebellion were an all-guitar collective active from the late 80s that recorded two fine albums, Pesky Digits (1991) and Touch Wood (1994), and it was Gavin’s stewardship of this unusual grouping that led English master guitarist Robert Fripp (the King Crimson guru) to contact him, and ultimately, to his membership in Fripp’s League Of Crafty Guitarists.

Fripp – whose sterling contributions to the work of David Bowie and Brian Eno alone are inestimable – took a Guitar Craft workshop in Auckland in 1990, at which the members of Gitbox Rebellion were in attendance. At the end of the course, Fripp offered Gavin membership of his League Of Crafty Guitarists group, and he subsequently spent the next two years touring with Fripp’s ensemble, giving workshops, and working on their albums.

When Gavin returned to NZ, the Gitbox album Touch Wood was recorded, and it would be issued by Rattle in his adopted country, and by Fripp’s label DGM in foreign territories. “It would probably have got awards if people knew it was a New Zealand album!” he says.

In 1998 his first solo turn, an album of treated electric guitar loops and multitracks, Music For Flem II, was given a limited release. “I’ve always had people telling me ‘you should do music for films’,” he says. “I used to take it as a snide remark. I thought, ‘I know what, I’ll call it Music For Flem! It’s music for imaginary films, I guess.”

But it was Thrum in 2003 that rewrote the book, and established a new respect for Gavin’s work.

Half compositions and half improvisations, the album is an extraordinary exposition of craft, technique and boundless creativity, and the trick is that despite its exploratory nature, it’s also a really gorgeous listen: “The beauty with acoustic guitar is that it’s an acceptable sound, even though you might be playing horrendous intervals and stuff that could sound quite dissonant on a piano.”

That sound was enhanced further by a custom-made seven-string guitar, which often sounds like two or three guitarists playing in unison. Four years later, in 2007, he released Visitation, another excellent all-acoustic proposition, but this time augmenting the seven-string instrument with a Glissentar, an 11-string acoustic instrument that resembles an oud.

Gavin continues to perform in a startling range of contexts, including regular appearances at the outsider improv sessions known as Vitamin S, where anything can happen, and he is working towards a third solo album that promises to reinstate electric guitar.