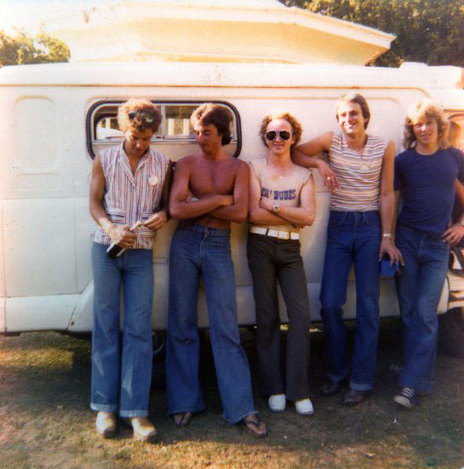

As a Jew, White was outnumbered in Th’ Dudes, but as their bass player he was in the perfect spot to turn a satirical eye to their foibles. His companions were three convent schoolboys and a meat’n’spuds drummer, living out their fantasy of being Glendowie’s Rolling Stones (or at least, its Hello Sailor). They were arrogant, they were snotty, and to many rock fans – especially the burgeoning punk scene – they were prats. Their most devoted fans sometimes seemed to be schoolgirls and their svengali manager Charley Gray, but classic-rock radio playlists confirm that they were good talent spotters.

The attitude of Th’ Dudes may have alienated some, but they had many supporters who got past the posing and saw the potential. When Radio With Pictures host Barry Jenkin announced Th’ Dudes demise in May 1980, and Rip It Up reviewed their posthumous second album Where Are the Boys, both expressed regrets that the band’s posturing had prevented them from getting the cred they deserved. Years later, that would come. Those who threw eggs during Th’ Dudes’ set at Sweetwaters 1980 were obliged to suck them, and many disdainful rock fans realised it was they who had taken rock and roll too seriously. Meanwhile, Th’ Dudes were doing themselves damage having all the fun.

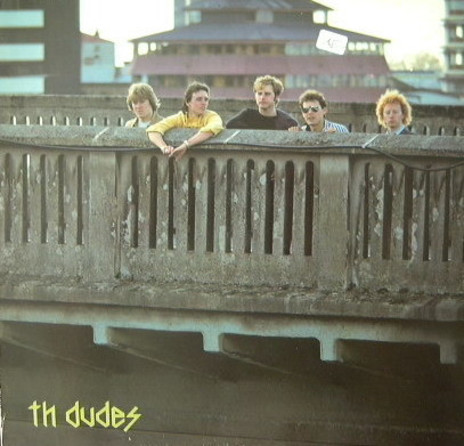

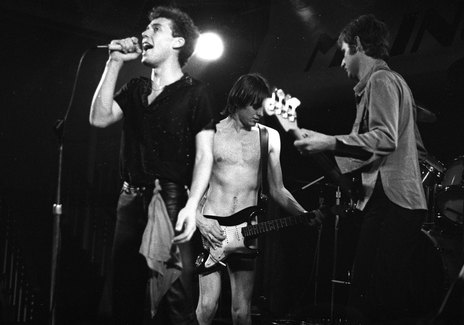

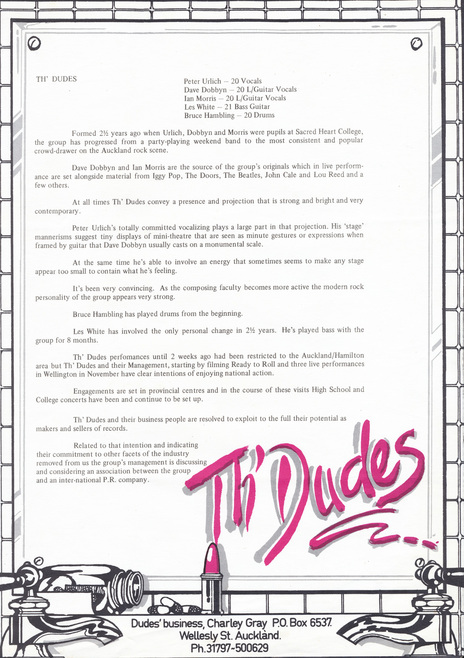

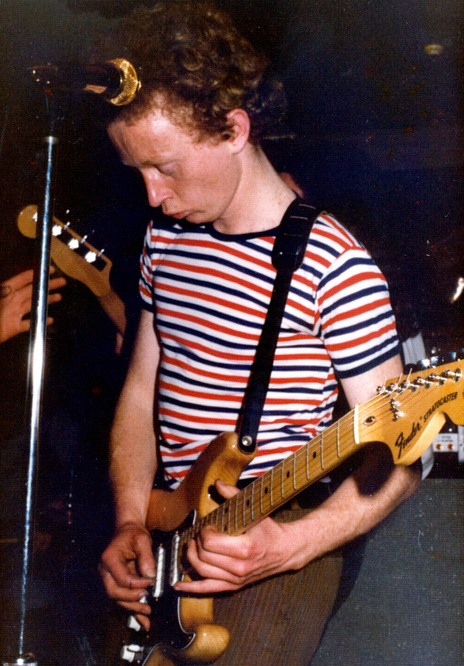

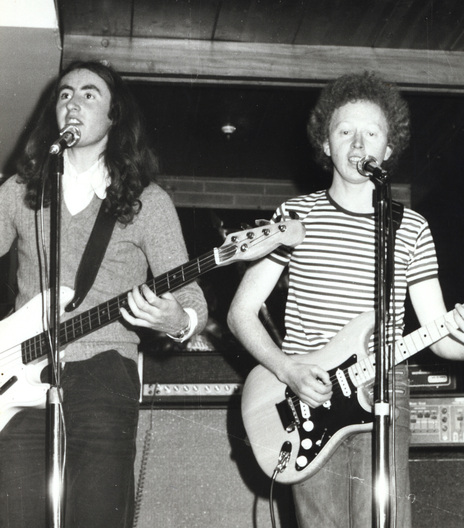

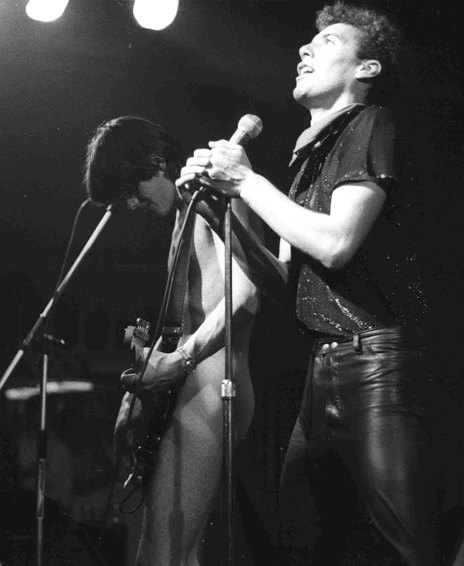

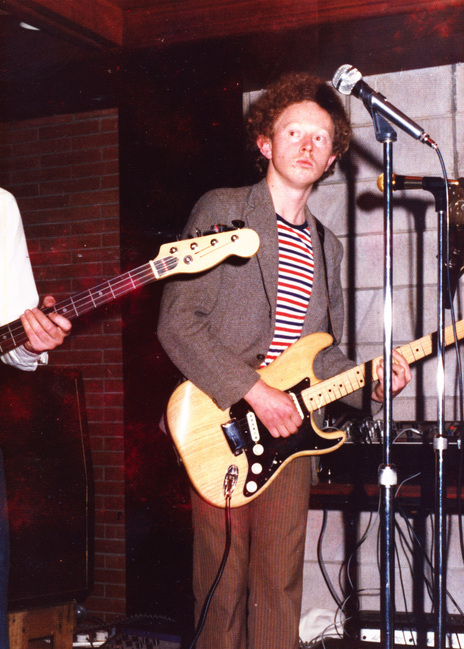

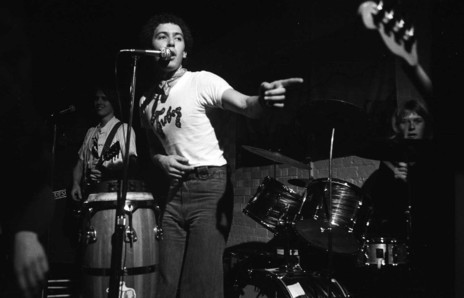

Named after a catchphrase of New Musical Express cartoon character Th’ Lone Groover – with perhaps a nod to Mott the Hoople’s biggest hit ‘All The Young Dudes’ – the name gelled as if it was destiny. Peter Urlich was the perfect frontman: confident, good-looking, and a natural showman in any era. Bruce Hambling and Lez White were one of New Zealand’s best rhythm sections, and aptly named: Bruce’s solidity balanced Lez’s flamboyance. And guitarist/songwriters Ian Morris and Dave Dobbyn did their homework, flicking through their favourite albums: The Rolling Stones, The Beatles, Iggy Pop, Mott the Hoople, Bowie, the Velvets, Graham Parker, Elvis Costello.

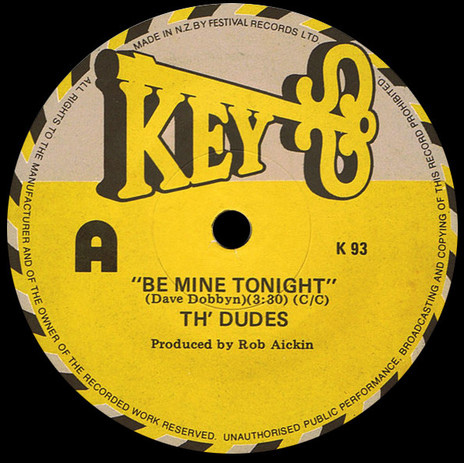

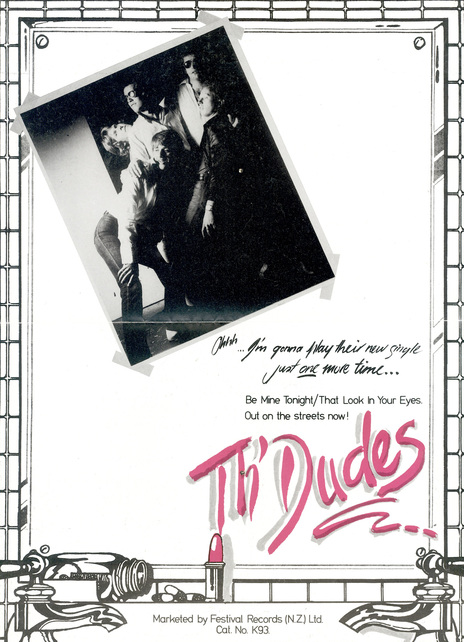

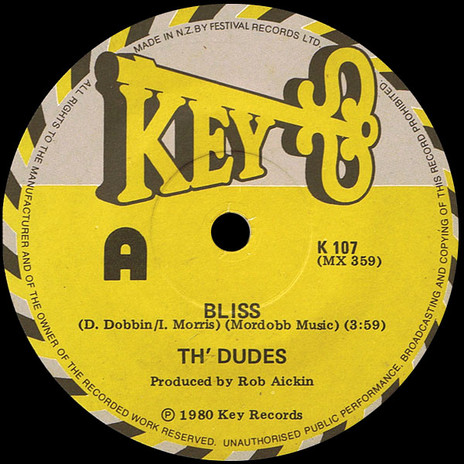

Songs such as ‘Be Mine Tonight’ and ‘Bliss’ became national anthems.

They combined their influences, served an apprenticeship crafting their showmanship and songwriting, and stayed alert to the revitalising energy of punk. At countless live gigs and with unlimited studio time at Stebbing, they emulated their heroes, recreating familiar riffs and hooklines until they came up with their own classic originals. Songs such as ‘Be Mine Tonight’ and ‘Bliss’ became national anthems, and several others were almost as popular: ‘Walking in Light’, ‘Right First Time’, ‘That Look in Your Eyes’. On the albums were surprises such as the manic ‘You Got Something’, the poignant ‘Lonely Man’, and the epic ‘There You Are’.

Mocked by many at the time, the legacy of Th’ Dudes is significant. The band set a standard in original songwriting, in stage and album production, plus management that would eventually become an industry norm. It was more than just a launching pad for its stellar frontline of Peter Urlich, Ian Morris and Dave Dobbyn.

School daze

The trio met at high school in the late 1960s. Sacred Heart College is situated in Glen Innes, in Auckland’s eastern suburbs, and had recently seen Tim Finn and Neil Finn, and Mike and Geoff Chunn pass through its portals. In Split Enz, Crowded House and Citizen Band, they would all have a lasting impact on New Zealand music.

Looking back in 1994, Dobbyn recalled, “There was only one time that could have happened,” says Dobbyn. “I don’t know why it did. I was aware of the others. There was always this kind of club of people who didn’t fit in. We weren’t sporty, we were underachievers who would hang out and play records most of the time. And the music that was happening, there were some pivotal things. I remember waiting for the minute the bell rang so we could go down and buy Abbey Road. That was monumental.”

A crucial factor was the music master, Ivan Gannaway, a Marist Brother and “a beatnik in disguise” according to Mike Chunn. He championed Bob Dylan and The Beatles, encouraged live performance, and the use of the music rooms for pop band rehearsals. He once conducted the whole school singing ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’ in the assembly hall.

Morris and Dobbyn first met in 1968, in Form One. Dobbyn arrived late for the first class. Over 30 years later, Morris described the scene: “The moment he walked into the classroom is burnt onto my retinas. He was white, he was whiter than white. With ginger hair, which his mother had just cut with the kitchen shears. He was wearing the navy blue uniform handed down to him by his brother, a huge blue uniform. He looked so unusual. And when he walked late into a room of 50 kids – there were huge class sizes then – the room fell into silence. This poor guy walked in there and looked around, and everyone burst out laughing.”

Ian Morris immediately felt that Dave Dobbyn was a kindred spirit

Morris, recently arrived from Britain – to his regret, his parents had emigrated shortly after Beatlemania hit – immediately felt Dobbyn was a kindred spirit. “I’d found the adjustment hard – England is a very reserved place, and New Zealand much more outgoing – so I found it quite hard to fit in, I was a bit of a loner. So when Dave walked in I empathised with him: I could sense that he had this loner’s feel about him. We hit it off right from day one, we were best mates. We both loved music, loved the same songs, and had a similar sense of humour. We loved Peter Sellers and the Goons, John Cleese, I’m Sorry I’ll Read That Again – absurdity and music – and we found such brotherhood in that.”

Dobbyn always played the guitar by ear, said Morris. “He always knew what was good, what was cool. At lunchtime everybody would be sitting round and the boarders would be trying to learn the chords to ‘Father and Son’ – and Dave would come in and play ‘Old Man’ by Neil Young, something with grit in it rather than Cat Stevens. He always had that rock and roll thing about it. When Abbey Road came out everyone wanted the chords to George Harrison’s ‘Here Comes the Sun’ – all the boarders would be sitting there with their capos – and Dave would play ‘Come Together’, something grubby – something with grit.”

And Peter Urlich? “He was the same at school as he is now, Mr Sociable,” said Morris in that 2001 interview. “A very sharp dresser, with creases in trousers even when he played rugby. He got on with everyone, he was a teachers’ favourite, but got on with the bad kids too. He knew how to spit. He loved music, he loved the singers, Mick Jagger and later on, Bowie. He loved the "star" thing: Stardom and the whole pop thing. You’ve got to have that. If you don’t love the star thing, then you can’t be in a pop group I’m afraid. You’ve got to want to be a star.”

That was one ambition not shared by Dobbyn, however. “There were some things I wouldn’t do,” he said in 1994. “I wouldn’t perform at school. There was a music competition there called the Walter Kirby Prize that was like the zenith: if you won something in that, you acquired this respect from the whole school.” The Finns, the Chunns, and Ian Morris and his brother Rikki all had their moment in the Walter Kirby, but not Dobbyn. Meanwhile, Morris recalled that he and Urlich dreamed of being one of the great “star duos: Mick and Keith, Bowie and Ronson, Ian Hunter and Ariel Bender – we just loved the rock and roll dream.”

Learning the ropes

While Urlich worked on his moves and on holding notes, Morris worked at home: His parents bought him an electric guitar while on a trip back to Britain. He slowed down Rolling Stones’ albums on the family gramophone to 16rpm to learn Keith Richards’s licks. Always someone who had enjoyed experimenting with tape recorders, Morris secured a job at Stebbing Recording Studio as a “junior engineer”. He made tea, ran off countless copies of jingles to send to radio stations, and quickly learnt how to run a recording desk. “Apart from the BBC or Abbey Road, I can’t think of any better training experience for an engineer.”

In 1975, Morris joined Chillum, a band featuring former Glendowie College boys Andrew Bayliss, Glenn Owen and Bruce Murdoch. They played for dances at the local tennis club: Creedence Clearwater Revival songs, Chuck Berry songs. After about a year, Urlich joined as the singer. “He brought a level of professionalism and a work ethic that he brings to everything,” recalled Morris. “We got more gigs, learnt more songs, and became a lot better as a band. That band broke up about the time I left school, but Peter and I asked Dave if he wanted to join a band. After much umming and ahhing, he agreed.”

While his friends had been making their first steps on stage, Dobbyn had been practising his guitar at home. Slowly the loner came out of his shell. “As soon as we realised that playing music meant you could play at parties, and there were girls at parties, and you’d have all this fun, it was so exciting,” said Dobbyn. “It’s a cycle everyone goes through. It was the most exotic thing to be a pop musician.”

A short-lived band featured Gary Langsford on guitar, later a member of the Top Scientists and DD Smash. Morris: “We did gigs at Surfside at Milford, which Neil Edwards [ex-Underdogs] was running at the time. We’d do ‘Freebird’ by Lynyrd Skynyrd, Chuck Berry – and Gary would make us play Chaka Khan songs, which of course we couldn’t.”

The original bassist was another schoolfriend, Peter “Nyolls” Coleman, who was studying to be a doctor. They advertised in The NZ Herald for a drummer, and began auditions. After a few no-hopers, Bruce Hambling arrived. “Dave started the riff to ‘All Right Now’ by Free,” said Morris, “and Bruce came in on that downbeat. It sounded like Thor letting rip with his hammers. Really, that’s the moment Th’ Dudes became Th’ Dudes.”

Hello sailor looked like Rock stars, said Morris, “and that's what we wanted to be”

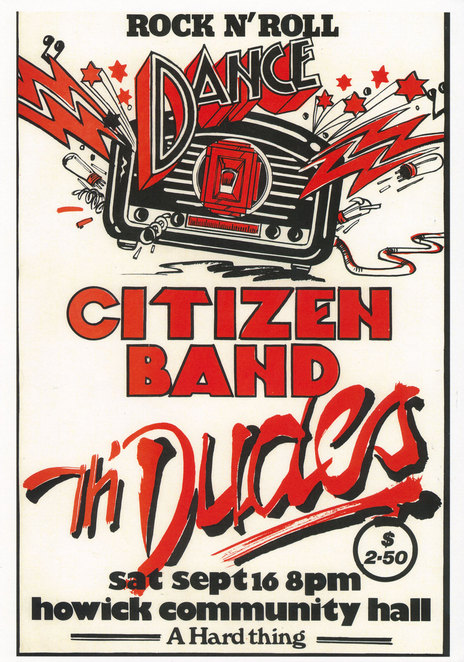

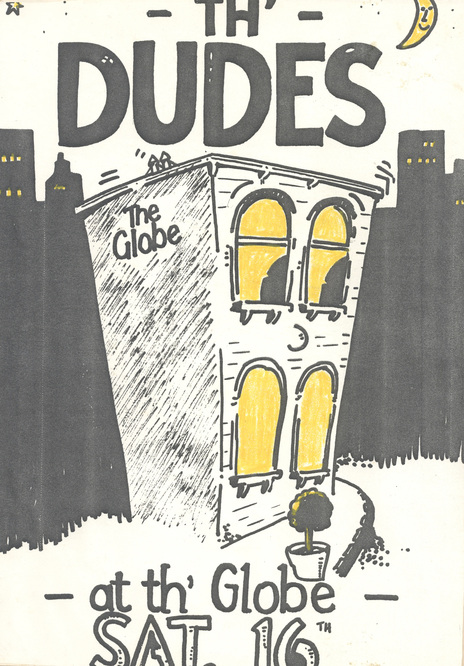

Stepping out

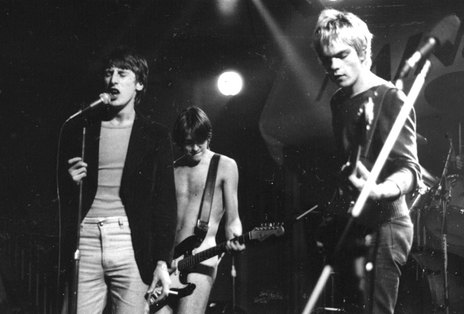

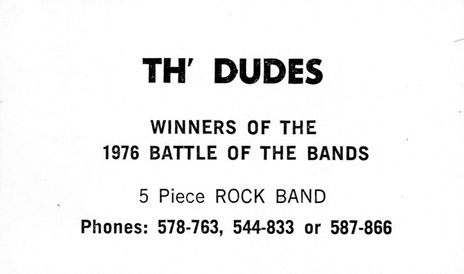

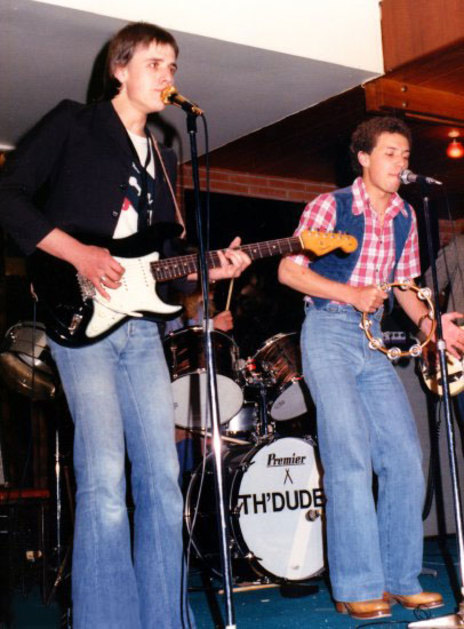

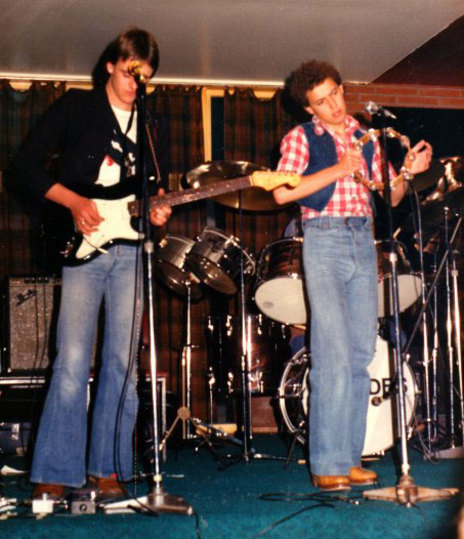

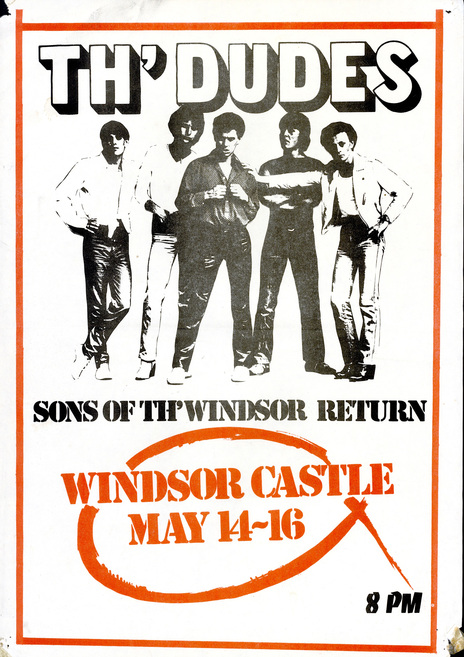

The band made its debut at Croft’s nightclub in the city. They played for free but the gig led to a stint playing at the Windsor Castle in Parnell. While just a “scuzzy pub”, the Windsor was a leading venue thanks to the popularity of Street Talk, which had just disbanded. “We were away, and went from strength to strength,” said Morris. “We won the Battle of the Bands that year, 1976 – we won three gold microphones and some terrible T-shirts. We played a set of cover songs, something that would never happen these days. No one did originals back then.”

Another band in the competition did. How’s Your Father was the first band of singer Jenny Morris. Besides their original song, and their singer, the band’s bass-player was memorable: Peter White.

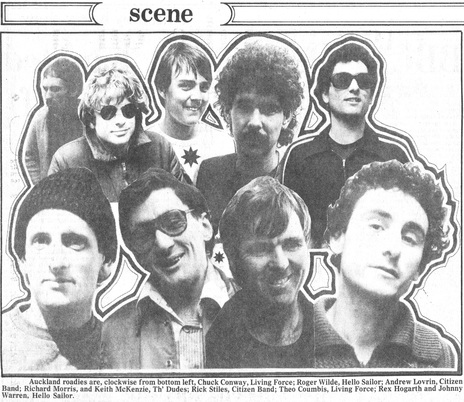

Over the next year, Th’ Dudes played many gigs across Auckland, often crossing paths with Hello Sailor, who were quickly becoming a drawcard – and a “huge influence” on Th’ Dudes, said Morris in 2001. “We even did a lot of their repertoire – even Hello Sailor did cover songs in those days, so we did Bowie and Iggy Pop. They developed this very distinctive Auckland sound, a combination of the Polynesian thing, the Stones, Lou Reed, and Iggy Pop. They were our heroes for a year, 18 months. We didn’t model ourselves on them but were influenced to a great extent by their whole attitude. They were very sexy, a bit grubby, and listenable. They looked like rock and roll stars, and that’s what we wanted to be. Because of our tight-arsed Catholic upbringing we could never be that type of rock and roll star, but we certainly aspired to it.”

While Urlich took notes on Brazier’s stage act, Morris recommended to Eldred Stebbing that the studio record Hello Sailor. In 1977 he would engineer their debut album, receiving a lot of acclaim for the drum sound on ‘Gutter Black’.

Charley Gray

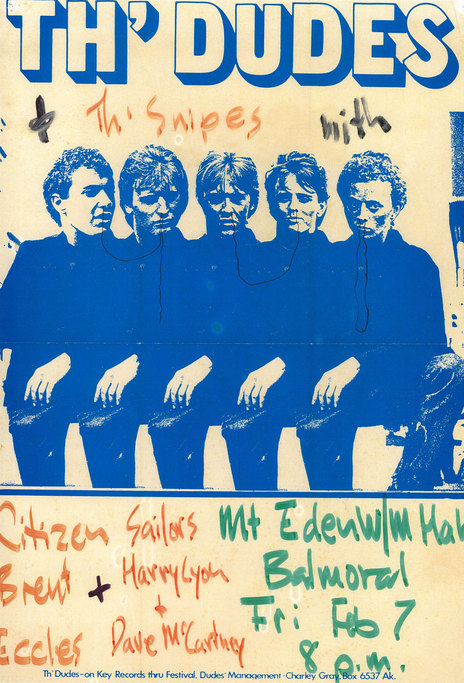

Peter Coleman bailed out in mid-1978 to concentrate on his medical studies, and the band recruited Peter White from How’s Your Father. To avoid confusion with Urlich, he began using his middle name, becoming known as Lez White. Also around this time, the band approached Charley Gray to become their manager. Gray was a former jazz drummer who, with his wife Ann, had recently founded a non-licensed venue called the Island of Real, on Airedale Street.

Gray had drive, energy, a flair for marketing – and for demanding that the band be treated with respect. His insistence that the live music industry lift its standards certainly achieved many of its goals – with better accommodation and meals for touring acts, and stages with three-phase power – though it didn’t win him many friends among venue managers. Looking back in 2006, Peter Urlich said: “We used to love these confrontations because Charley would puff his chest out and go, ‘That’s the way it’s going, otherwise we’re not playing – you’re not booking us.’ It was like the showdown at the OK Corral.” To journalists, as well, Gray was something of a phenomenon. The Auckland Star critic Colin Hogg recalled, “You’d look at Charley Gray and Th’ Dudes and think, who is the star here? Because Charley was so manipulative and pushy and demanding. ‘I’ve got an ad – where’s the story?’ It was all a bit … new.”

Charley Gray had drive, energy, and a flair for marketing

In 2006 Gray explained, “Nine weeks they went away on one tour. It’s not getting too far up yourself to say, ‘Hey, couldn’t I have a half-reasonable motel room by myself?’” The attitude – “if you want to be treated like stars, you have to behave like stars” – was something the band didn’t always embrace to their credit. Gray recalled ruefully, “It doesn’t necessarily follow that if you want to be a star you have to behave like a pig.” The use of shaving cream to redecorate motel rooms was a Dudes trademark, but in professional matters – such as adequate stage equipment – they had good reason to stand their ground.

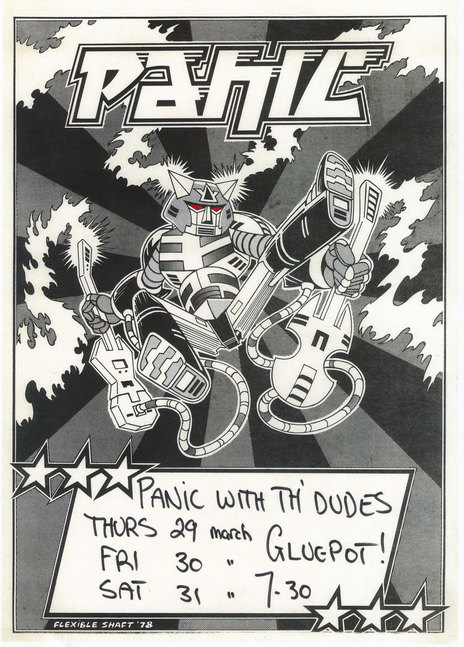

While Th’ Dudes were situating themselves to become the next big thing in New Zealand rock, the punk movement had captured many fans and launched many bands, with musicians who had barely held an instrument. To them, Th’ Dudes were the enemy; they preferred the band of that name from Dunedin. Chris Knox of The Enemy and, later, Th' Dudes’ rivals Toy Love, said in 2006: “Largely, as punks, we despised the pub rockers. They were the thing we were fighting against. They were the forces of mainstream blandness of musical correctness. The fact that you had to play really well to get up and play before these people.”

Punk influence

While Th’ Dudes had mainstream success as their goal, it was on their terms, and they weren’t oblivious to the stripped-down ethos that punk championed. “We were a bit older than the punk contingent. We played a lot of what you might call clever music,” said Morris in 2006. “We had a grounding in musicianship. And when the punk thing happened, we were able to grasp the best bits of that and make it razor sharp. We didn’t follow the fashions or politics of it, but punk showed us you don’t have to be clever and smart in your songwriting – you can just have three chords and have a good song. That sharpened our songwriting.”

The punk influence is especially apparent on album tracks such as ‘Can’t Get Over You at All’, ‘Spitball Speed’ and ‘All My Lovers’. “We grabbed the best of both worlds,” said Morris. “We could grasp the melodic structures of the past, where melody and chords were important, and we also grabbed the energy and simplicity of the new music. I never bought a record by the Sex Pistols or the Buzzcocks, but the excitement of that whole time – it was unavoidable.”

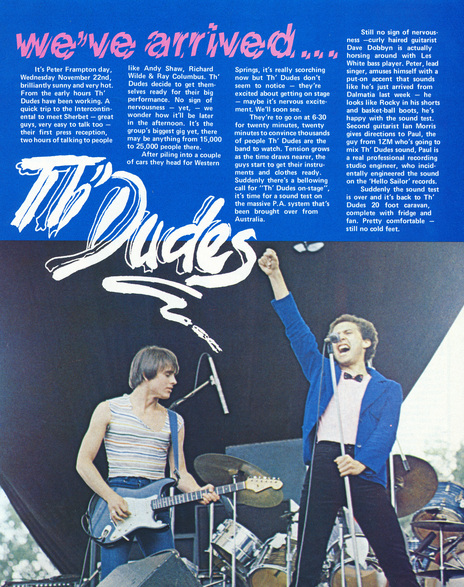

Gray saw the advantage of building an audience for the future by booking lunchtime gigs at secondary schools, as well as the usual evening shows at licensed venues. A television item filmed in 1979 shows them arriving at a girl’s high-school in a long limousine – hired, not for the day, but for the hour. To the band, this type of swagger was all part of the fun, but it attracted barbs for those not in on the joke. Promoter Benny Levin was askance when the band arrived for its support slot at the massive Peter Frampton show at Western Springs in late 1978, towing a caravan that was bigger than the main act’s dressing room. It cost them more than their fee, and they had yet to release a record.

While building this reputation for bravado, the band was also making its name as songwriters. For their first single, Th’ Dudes played their trump card, ‘Be Mine Tonight’. A six-minute epic – more bravado – written by Dave Dobbyn, and arranged by Ian Morris, it would become a much-loved and imitated New Zealand standard thanks especially to its exclamatory chorus, “I knew you … not long.” (When starting out, The Verlaines covered the song. According to John Dix, “its jangling guitar was particularly influential on the Dunedin sound”.) ‘Right First Time’ was the follow-up, an extremely radio-friendly song that didn’t waste a moment, had an anthem for a chorus, and showed Morris’s experience in the studio and love of pure pop. While the songs’ appearances in the New Zealand sales charts were brief, peaking at No.36 and No.34 respectively (Toy Love’s ‘Rebel’ made No.29), radio-play helped pull crowds during months of constant touring.

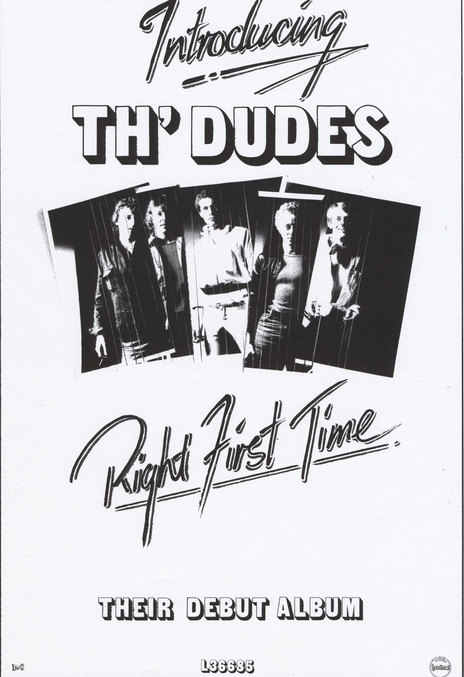

Spin me another line

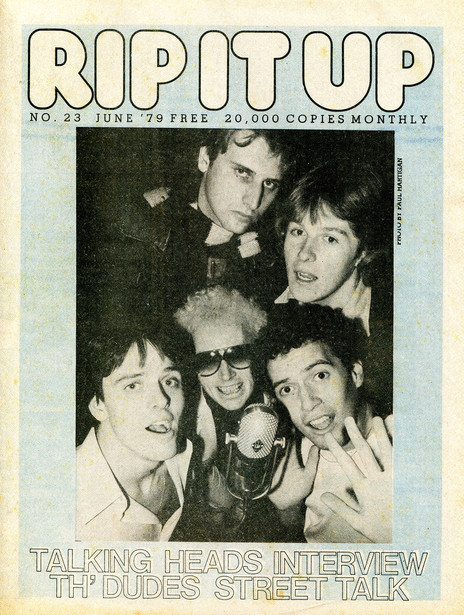

Right First Time was Th’ Dudes’ debut album. In Rip It Up, writer Dominic Free encapsulated the attitude of many when he opened his review, “No exaggeration here, but there was a time when New Zealand albums were dreaded by reviewers. Presenting as they did the dilemma of either deluding the record buyer or discouraging the local bands, it was damn near a suicide mission to review them. Now those days are over.” Preamble over, he continued: “… the album is a pretty consistent winner. There is simply no substitute for strong melodies and the songwriting team of Dave Dobbyn and Ian Morris can consistently come up with the goods in that department. Having done the really difficult part they make no slips with the arrangements, which consistently bring the best out of the material.”

Morris’s years in the studio made him almost Rob Aickin’s co-producer, tightening arrangments, finding the right effects to capture the sound required, even if the influences were apparent. ‘That Look in Your Eyes’ was inspired by Revolver-era Beatles, but hints of Roxy Music, solo McCartney and even the Eagles can be heard. ‘On Sunday’ has the pumping 4/4 rhythm that was much used by Dobbyn’s DD Smash in its early period, and the fade-out references Sgt Pepper. They pay tribute to Hello Sailor on ‘Billy Be Bad’, Bowie on ‘Stop Crying Now’ and Beggar’s Banquet-era Stones and Thunderclap Newman on ‘There You Are’.

The album showed their confidence; the singles showed their originality. In 100 Essential New Zealand Albums, Nick Bollinger wrote of Right First Time: “Th’ Dudes’ debut album is great because it had to be: anything less would have run counter to the group’s sense of itself. From the beginning they willed themselves to be special … listening to Right First Time three decades on, you are struck by how accurate the title proved to be.”

Tensions rose to the extent that Lez White and Dave Dobbyn – neither violent men – came to blows.

Th’ Dudes barely touched ground in 1979, constantly touring, enjoying every cliché of rock and roll decadence, and spending countless days in the recording studio. Tensions rose to the extent that Lez White and Dave Dobbyn – neither violent men – came to blows. White connected with Dobbyn’s jaw, breaking his own wrist and putting himself out of action for a few weeks. And the band caused headlines in Wellington when, at late notice, they refused to play an Anzac Day concert at the Opera House because the PA wasn’t up to scratch. Unworried, the support acts Rough Justice and the Wide Mouthed Frogs went on anyway.

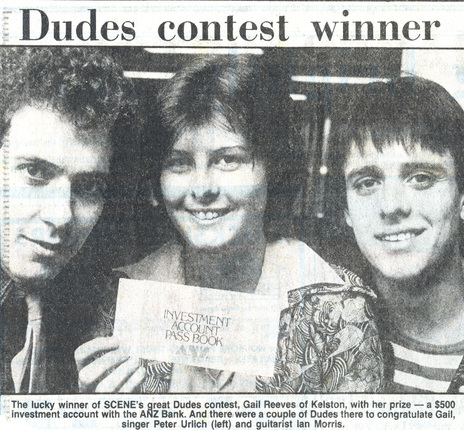

For their national tour to support Right First Time, Th’ Dudes recruited fulltime roadies, hired trucks for state-of-the-art equipment, and secured a sponsorship from ANZ Bank. While this would soon become standard, at the time it seemed more of a statement, and a backlash seemed inevitable.

Touring Australia

November 1979 can be seen as the moment when Th’ Dudes peaked. They were invited to support UK act the Members on their Australian tour. Morris remembered the month-long tour as being “great fun, but hugely awful at the same time”. The experience was a wake-up call as to their possible future if they wanted to fulfil their ambitions. It would have been “Fear and loathing in Wagga Wagga,” Urlich said in 2006. “We’d be crammed into a rental car, drive four hours only to play at 7.30pm at the bottom of the bill beneath bands that weren’t very good. We’d come from adulation in New Zealand to 'Get off!' in Australia. That showed me what it would be like in Australia. We were nobody. We could have just gone over there and got lost in the dust.”

While on tour, they made an overnight visit back to Auckland to attend the annual music awards. They won the awards for Best Single (‘Be Mine Tonight’) and for Best Group, but on national television they came across as white punks on dope, arrogant and contemptuous. “We’d like to thank Charley Gray,” a peroxide-permed Dave Dobbyn told the music establishment in the room, “who you all hate.” John Dix saw the moment as summing up the dilemma of Th’ Dudes. “Unfortunately, this rebellious side of the group was one which few detractors saw. They may not have been punk rockers, but they were punks. In November 1979 few NZ bands could match them for sheer audacity and a non-compromising attitude towards the industry. But all their critics saw was wimpoid prima donnas.”

Next day, Th’ Dudes were back in Brisbane, warming up an audience that was disinterested at best, if not drunk and hostile. Morris in particular was haunted by what the future entailed if they were to try and break into the Australian market: Endless highways, macho aggression from industry and audiences, a hand-to-mouth existence. “Back then there really only was one way to go – and that was to go somewhere else and hope to get some record company pick-up. We toured non-stop for two years. We reached the stage that we thought, What do we do now? We can’t keep touring relentlessly. It’s going to drive us mad.”

Where Are The Boys?

In January 1980, what should have been a crowning moment – playing the first Sweetwaters festival in a prime slot just before the headliner, Elvis Costello – was instead bittersweet. A sector of the crowd was determined to give Th’ Dudes their comeuppance, pelting them with eggs throughout their set (one of the perpetrators was Tim Mahon, later of Blam Blam Blam). Th’ Dudes rose to the occasion, and were fired up to give one of their best performances ever, but the experience did suggest that something had to give.

The band was sapped of its energy, not helped by a lifestyle which burnt the candle at both ends and more than a few brain cells. The end came after three months of playing disinterested gigs to diminishing audiences. Morris took Dobbyn aside and told him he was leaving; “Dave went into a state of shock,” he recalled. At the Windsor in April both Morris and Urlich told the audience they were quitting. The final gig came a week later at Mainstreet. To Gray’s horror Morris – fuelled by Jack Daniel’s – performed in the nude, wearing only his Stratocaster.

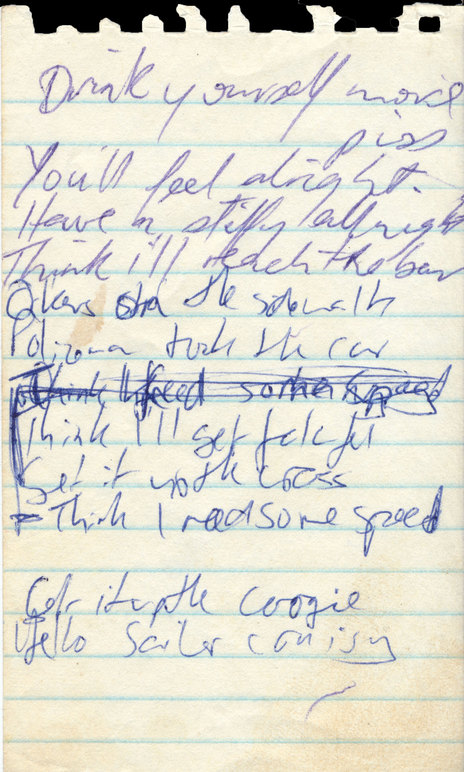

From their Australian experience came ‘Bliss’, a parody of the hard-drinking pub crowds.

Th’ Dudes had been one of New Zealand’s most promising rock bands; to provide a worthy epitaph, they returned to Stebbing studio to complete a second album. ‘Walking in Light’ had already been released in late 1979, a strong track that combined rock and roll with an electronic disco strut, like a mix between the Rolling Stones’ ‘Miss You’ and Blondie’s ‘Heart of Glass’. From their Australian experience came ‘Bliss’, a parody of the hard-drinking pub crowds and their need to sink more piss. Driven by fiery guitar lines from Dobbyn and a confident, throbbing bass from White, naturally it became a drinker’s anthem.

Despite being a final statement, the album shared the ambition and confidence of their debut, albeit with a tinge of fatigue. The title – Where Are the Boys? – came from the track ‘The Modern Choice’, a weary reflection on growing up in public: “Back in the old years/ my children would never understand/ I’d do it all again.” Dobbyn’s ‘Lonely Man’ is similarly drained and philosophical. But there is also a sense of indulgent fun about the album, with Morris throwing the kitchen sink at his arrangements, and crafting the mix (he co-produced with Rob Aickin). They didn’t forget that they were a party band, with the punchy ‘You Got Something’ channelling the Attractions and The Beatles, the Urlich-written live favourite ‘On the Rox’, and ‘All My Lovers’, an angry punk sneer from Dobbyn that can’t resist a pop chorus. The closing moment, ‘You Can’t Make Me Dance’ is a high-tension blend of punk and psychedelia.

In 1988 Morris looked back at the sessions with some pride. “It was great, being able to work with your own stuff like that, but it was very hierarchical: Dave and I at the top, then Peter, then the rhythm section, Bruce and Lez. But it was very much Dave and my ideas in the end. Our strengths? Probably what they are now – Dave writes some great lyrics and great songs and I put them together, sonically. In those days we were throwing the extraneous in. We’d think, ‘Oh that’s a great lick, we’ll have to use that.’ So it ended up being a real porridge. Far too many things going on. But there’s some good stuff there.”

RipItUp’s reviewer Stephen McDonald described the disc as a decent, “end-of-an-era sampler” and expressed regret that this “hot little combo” had broken up, its ambitions abandoned. “While they may have been butts for the wit of the hipper-than-thou set, Th’ Dudes can be quite satisfied with what they did achieve … wherever you are boys, you did okay.”

Dobbyn – who took the band’s demise very hard – said the album brought some kind of dignity to the end. “We cared very much about each other,” he said in 2006. “More than we knew, really.”

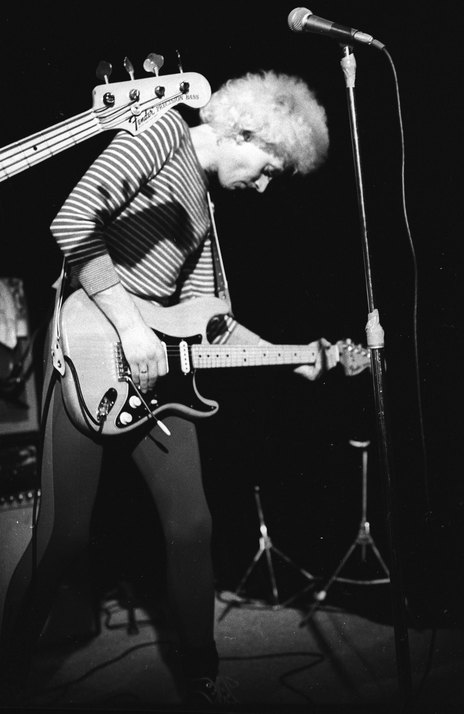

In the early 80s, the frontline of the band quickly established new careers that would sustain them for the next quarter-century: Urlich as a club DJ, singer and bon vivant; Morris as a busy producer of albums and jingles, and a temporary chart-topper in his persona of Tex Pistol; Dobbyn as … Dave Dobbyn, beloved entertainer and writer of universal anthems. Lez White continued to be an in-demand bass-player for bands such as the Broken Dolls, Daggy and the Dickheads, and Graham Brazier’s Legionnaires, until his departure overseas in 1984. Bruce Hambling left the music industry.

Twenty-six years after their last show at Mainstreet, Th’ Dudes succumbed to temptation and reunited for a nationwide tour, sponsored by Radio Hauraki which was celebrating its 40th anniversary. The support acts were their one-time heroes – Hello Sailor and Hammond Gamble of Street Talk – and the venues were elegant theatres. They were packed to the gods with fans of several generations singing along to Dudes songs that had become part of a national soundtrack.

--

Rikki Morris’s collection of Dudes live photos

Murray Cammick’s photo sessions with Th'Dudes

Ian Morris on All the Young Dudes

Ian Morris interview on Give It A Whirl