Headed for greatness, by Simon Grigg

The Bones Hillman story is a very New Zealand one. It starts in the inner West Auckland suburb of New Windsor in 1958, where Wayne Stevens was born into the then new and close-knit small community. Many of those he grew up with – and started making music with – were friends from his pre-school days, names like Kevin Grey, Tony Baldoch, Kevin Hall and Jimmy Herbert.

New Windsor was not a wealthy suburb. North of Blockhouse Bay, east of Avondale, it was solidly blue-collar and back then rather isolated from much of the rest of the city. You had to make your own fun and as the group of friends went through kindergarten then primary and secondary schools together and moved into the workforce, music was a major diversion. These were tough, gnarly but incredibly warm and genuine young men who stayed close all their lives.

Nobody is exactly sure when they formed their first band, but the best guess would be mid-1975. Musically, older New Zealand was deep into prog-rock at the time. Younger kids, however, were dancing to another more concise rhythm, that of David Bowie, T. Rex, and The Glitter Band. On the periphery, the more raucous Lou Reed live records; for the adventurous, Iggy’s Stooges and the New York Dolls.

The band had a fairly fluid line-up but soon centred around Wayne (by now nicknamed Bones because of his height), both Kevins (Kevin Hall would soon be known as Spike Bastard), and Jimmy (aka Jimmy Sex). The instruments were also fluid and Bones started on the saxophone.

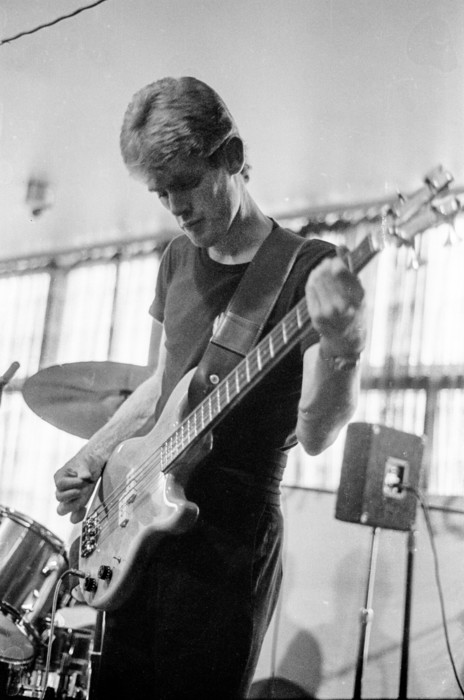

In 2014, he told Anne McCue on Nashville’s WXNA that he “started out on a saxophone – I used to sound like a duck that had been shot. No one wanted to play bass, so when the little pool of kids from school said, ‘c’mon, let’s start a band’, there was a big gap on bass and I said, I guess I’ll do it, and it was natural for me, I understood – I could actually put records on and pretty quickly I could decipher the bass parts. I caught the bus in on a Friday night and bought a $90 bass. Saturday morning, I woke up and it was out of tune so I took it back: ‘Ah, you have to tune it, son’.”

School friend Pam McDermott remembers a drum kit in his bedroom which he didn’t play very well. She loaned Bones the money for his first bass. “Jimmy suggested he might do better on bass, and the rest is history.”

Their early practice room was, thanks to a patient Dad and the proximity of the others (the Greys lived next door and the rest were close), Bones’ basement.

The band went through several names: The Avondale Spiders, The Metal Masochists, MM and The Vandals, before eventually settling on The Masochists. The prototype punk band, who probably have a decent claim to being the nation’s first and the local equivalent of Australia’s Radio Birdman in that their influences pre-date UK punk, played a handful of gigs. Spike recalls gigs at St Chad’s Hall in Sandringham (“a disaster”), a couple around Mt Roskill and others in a hall in Morningside.

By early 1977, they had rented a space in Karangahape Road, above what is now The Rock Shop, and played there to invited audiences. That’s where I first met them in late May or early June 1977, having possibly been invited with the rest of the Suburban Reptiles after an encounter by one of us earlier – either that or we were walking past and were invited up. Both stories have advocates.

The Masochists were the real deal: proper punks and they could play.

For art-school us, they were the real deal: proper punks and they could play. Jimmy Sex had a scar on his cheek and our moodiness was manufactured, theirs not. Further encounters and a growing friendship led us to offer the band a slot at the forthcoming Angel Mine movie benefit on July 16 at the University of Auckland. Promoted by the director David Blyth and myself, it was the first major punk gig in the city and also threw The Masochists into the inner city in a very public way. The other bands, Suburban Reptiles and The Scavengers, were good and successfully dragged creativity from intentional chaos. But The Masochists – with their original tunes plus covers of the Velvets and The Stooges – played fiercely and without compromise, and stunned the audience. They had genuine menace. For the others, it was more of a stance.

It couldn’t last, however. Bad-boy antics and internal friction split the band in late September, shortly before they were supposed to support the Suburban Reptiles at a gig I’d booked in Disco D’ora’s in Newton Road. The Reptiles lost guitarist Johnny Volume at the same time so bassist Billy Planet switched to guitar and Bones was invited to join the band. His first gig was 1 October 1977 and he joined the band in time to play the basslines on their single ‘Megaton’ nine days later. The name “Hillman” arrived at the same time, when I needed a surname for a press release. Bones drove a Hillman Hunter.

Bones Hillman played with the Suburban Reptiles through to March 1978, leaving when he found the band a little “too formal and serious”. He then formed The Assassins, with Spike, Jimmy Sex, Geoffrey Fiebig (keyboards), Roger Roxx (vocals) and Dave Burgess (guitar), and they settled into a slot as a regular band at the punk club Zwines. They also travelled to Wellington as part of the New Wave extravaganza promoter Derek King took south in June.

As well as originals, their live set included covers of Patti Smith and Television: quite different to the Zwines standards that were Ramones, Clash and Buzzcocks covers. In October, after Burgess, Roxx and Fiebig left, the remnants added Kev Grey, and renamed themselves The Rednecks – essentially The Masochists under a new name. They played for a few months before they finally broke up at the start of the new year.

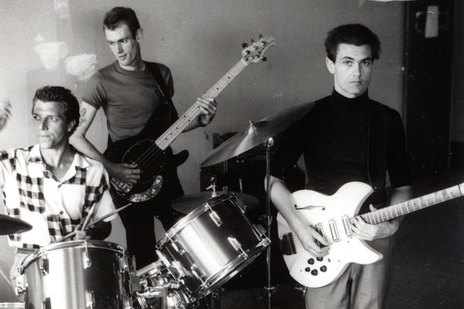

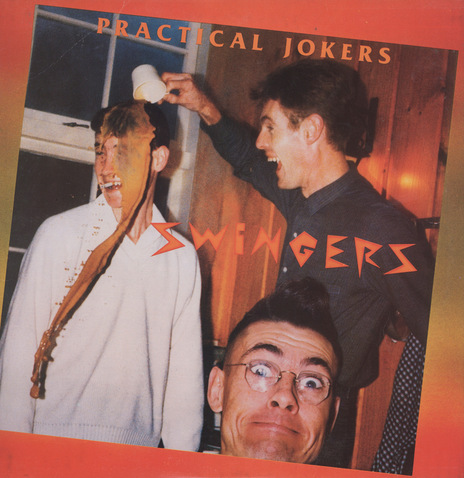

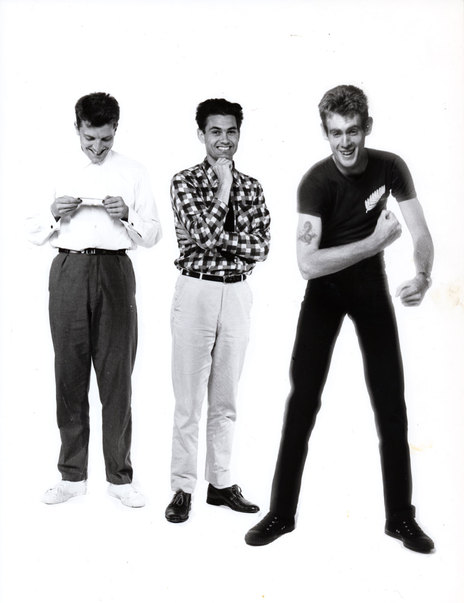

Meanwhile, ex-Suburban Reptile Buster Stiggs and former Split Enz guitarist Phil Judd (the latter after a mismatched attempt to join The Enemy) were putting together a band they were about to call The Swingers. Initially they planned a four piece with both Buster and Phil on guitar, a bassist and a drummer. Bones was offered the bassist position and accepted, joining in late 1978. Attempts to find a suitable drummer foundered so Buster moved to drums and the band settled as a trio before the year ended.

They immediately started writing and were soon recording, mostly at Mascot Studios in Eden Terrace. The songwriting credits were a three-way split despite Judd arguably providing the core of the early original songs. Buster added some of the late-period Suburban Reptiles tunes that were still unrecorded. Over the next 12 months they recorded an album’s worth of material at Mascot, plus sessions at 1ZM in Durham Lane for broadcaster Bryan Staff’s show.

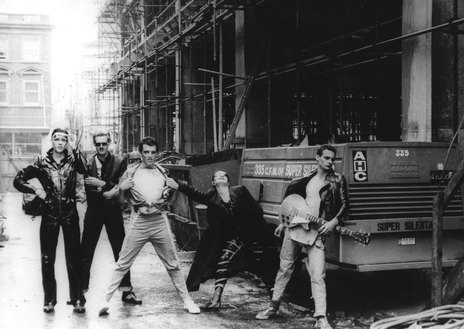

The Swingers’ first gig was an invite-only show at Ann and Charley Gray’s Island Of Real Café in Airedale Street in April. Despite the exclusivity, it was filled to capacity and the word spread quickly that the band was red-hot.

This was followed by The Swingers’ first public gigs, supporting Split Enz on the Give It A Whirl tour. The first of these was in Auckland in front of some 4000 people. The experience was disheartening, with the Australian road crew treating the Enz founder’s new band dismissively.

They followed the tour with a residency at Liberty Stage in the Edinburgh Hotel on Symonds Street, finding an instant crowd with what I once called the “Ponsonby villa-renovating crowd” – older and more monied than the audience Bones had played to at Zwines.

The Swingers were soon one of the biggest live draws in the Queen City.

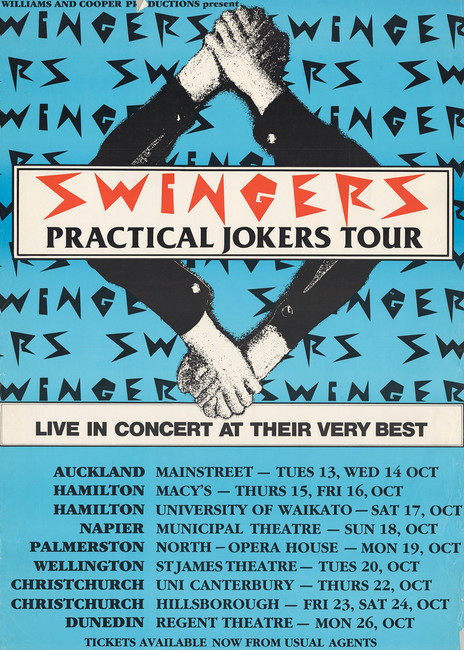

By mid-year, The Swingers were easily the one of the biggest live draws in the Queen City. Offers soon arrived from other parts of the country, importantly including bookings by Christchurch kingpin Jim Wilson. He took the band south twice where they wowed the Hillsborough crowd with what Buster Stiggs called “some of our best gigs ever”. If social media is any barometer, The Swingers’ reputation in Christchurch as a live act remains secure in 2020.

One of the songs they wrote during that flush of creativity started with Bones playing a simple riff in a practice. As Buster recalled to AudioCulture in 2017:

“What’s that?” said Phil. “What’s what?” says Bones. “That riff you were playing.” “Um, I dunno, what riff?” Phil had to physically press Bones’ fingers on the bass fretboard so he could play it and remember what he had done. Once he had, we were off. All the backing vocals came from Bones and I singing while we played through the song for the first time.

The song was ‘Counting The Beat’.

Two of the songs recorded by the band, ‘Baby’ and ‘Certain Sound’, were included on Bryan Staff’s AK79 compilation of Auckland punk and post-punk bands, which found its way into Auckland-only retail in December 1979 (and had a wider release in 1980).

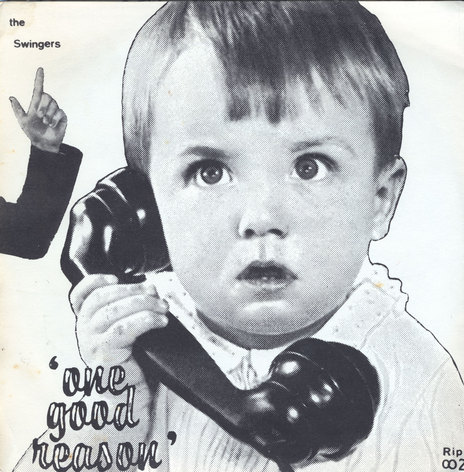

The band agreed to record further records (in a handshake deal) with Staff and Mike Chunn’s new Ripper label, although it was Staff who approached them initially. It was, he says, “Ripper’s best shot at the charts”. The initial result of deal was the May 1980 double A-sided 45 ‘One Good Reason’ (recorded at Mascot, with Mike Chunn co-producing with the band) and ‘All Over Town’ (a 1ZM recording by Bryan and the band). It charted respectably at No.19, largely driven by the band’s fan base as it was ignored by radio nationwide.

The next move was made by Mushroom Records boss Michael Gudinski, who offered the band a contract in June. By mid-July they were in Australia and in the studio, recording ‘Counting The Beat’. The single was eventually released in January 1981 and as history records, sold some 120,000 copies, peaking at No.1 in both Australia (six weeks) and New Zealand (four weeks, with four months in the Top 20).

The band was by that time already deep into the wearing and expensive grind that is the Australian pub and club circuit – and then the record company demanded an album.

Bones: “We were thrown in the studio really quickly, and then the band made a really stupid decision and fired the original drummer. He wasn’t fired because of his musical ability, he was fired because we were living in squalor and he was living in a nice house with friends. We were burning our furniture and starving, and he had a nice bed and Bremworth carpet. Then, because he’d co-written a lot of the songs, we didn’t record the catalogue we had, and we came up with another 10 new ones. We became a one hit wonder. We came out the other end totally in debt.”

The debt was somewhere in the region of $100,000 and the band was advised by Michael Gudinski that they were too far in debt and should break up, which they did in April 1982. Ironically, that one hit would go on to become one of the most recognisable, loved and commercially used songs ever recorded in Australasia, earning back the debt several times over across the years.

Bones rang his dad and asked for a ticket home.

Eventually, Bones rang his dad and asked for a ticket home. There, he first played with a few of his mates including vocalist John Wallis, in a band that somehow attracted the attention of US producer/hustler Kim Fowley, who asked for demos, which were duly recorded at Vidcom. The producer came back with a “not ready” response and no more came of it.

The final line-up of The Swingers included vocalist Andrew McLennan, who also returned to New Zealand after the split. He put together Coconut Rough, whose debut single ‘Sierra Leone’ was a 1983 No.5 hit in New Zealand – but the line-up that recorded it had imploded by the time it hit. In June 1984 McLennan invited Bones to join the band in order to support the song and the subsequent album.

“To feel and hear Bones on stage was amazing. Pitch-perfect weaponised high harmony vocals and the most propulsive bass playing in Christendom … he rang me post-Swingers and asked if he could work for a while with Coconut Rough. We did a couple of tours, threw Blams, Pop Mechanix and Swingers songs into the set and supported U2 over two nights.”

It was all over by January 1985 and Bones found work in a gas station. Having saved enough to buy a ticket, he headed back to Melbourne mid-year, moving into a flat with Sharon and Neil Finn in Porter Street, Prahran, taking up day work as a house painter. “I was happy and didn’t know if I’d play again,” he told Anne McCue in 2014.

However, play he did, with a band called The Bastinados, centred around two songwriters, Boris Falovic and Robbie Porritt, and managed by Buster Stiggs. Falovic had seen him around and eventually tracked him down at the flat (Enz bassist Nigel Griggs was a mutual friend) and he agreed to a rehearsal, joining the band shortly thereafter. Over the next year they played around the city, sometimes to sizeable crowds. The band were realistic, though, as Falovic recalls. “It was obvious that Bones was headed for greatness, but we were just a bit surprised when it ended up being Midnight Oil.”

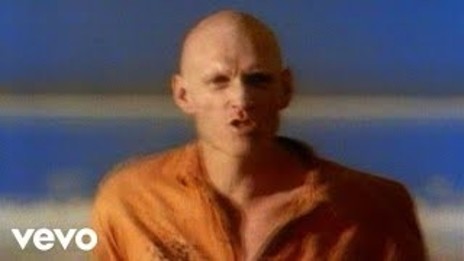

Bones: “One night when I got home from work, Neil told me that Rob Hirst from Midnight Oil had called, and that they were looking for a new bass player. Of course, I thought he was pulling my leg. Luckily for me, a few nights later Rob rang back again wondering why I hadn’t returned his call. He was actually quite serious. He offered to send me the Oils new album Diesel and Dust and asked if I could learn a few tracks and come up to Sydney for a bit of a play.”

Neil Finn said that Midnight Oil had called, looking for a new bass player. “I thought he was pulling my leg.”

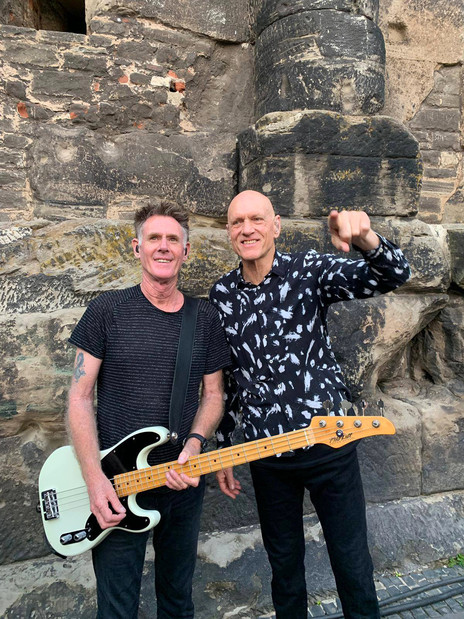

It was a journey that lasted until the end of his life. Bones played and toured as a member of Midnight Oil over countless tours and nine albums (three of which were live) and that global finale to an estimated one billion viewers at the 2000 Sydney Olympic Games with the “sorry” outfits (following Prime Minister John Howard refusal to apologise to Indigenous Australians) before disbanding for 15 years in 2002.

There were other projects too. In 1997, during a gap in the Oils’ schedule, Bones played and recorded with Melbourne electronica duo The Hunting Party (Bones and keyboard wizard Chris Abrahams), and in 2004 he headed to the US at the behest of Neil Finn to play on the sessions for the new Finn Brothers album being recorded in upstate New York, produced by Tony Visconti. He was thrilled that he would be working with musical friends and a producer who was a teenage hero.

It didn’t go well, as he told Anne McCue: “It was a very disappointing, maddening project. We recorded an album up there and the London Symphony added strings in the UK. And then they didn’t release it – the record company couldn’t hear a single or something. They then went back to LA and recorded the whole record again without us with Mitchell Froom – back to the safety net of the team. Tony Visconti was freaking out. He’s never had that in his life.”

It caused a rift with Neil Finn, which was later healed. When I ran into Bones in late 2004 in Auckland, he was still angry but more excited by the fact that he’d signed for Dave Dobbyn’s touring band (he plays on the 2005 album Available Light, which includes the much-loved ‘Welcome Home’). Based in Auckland between 2004 and 2008, he toured and recorded with the bard: “Playing Helensville and coming home that night? That’s fantastic, compared with playing in Detroit or Cleveland,” he told Graham Reid in 2004.

However, the end of the decade saw him offshore again, this time in Nashville where he quickly established himself as an in-demand session player, performing and recording with the likes of Sheryl Crow, Elizabeth Cook, Anne McCue and Tim Carroll amongst many, later moving to Milwaukee, Wisconsin. “Nashville turned music into a job for me. It had never been that, it had always been an escape from having a job and Nashville kinda treats musicians harshly. Enjoyed living there but don’t work there anymore.”

“I had to learn some new tricks," he told Russell Baillie at the Listener. “Just being the electric rock bassist had no pull in this town. For some reason, everyone wanted an upright bass. That resurgence of young people playing string band music just came into the culture.

“It really was an education. Just a different appreciation about playing,” he said. “I had no idea on that 747 flight out of Auckland I would end up playing upright bass with hillbilly musicians at the Grand Ole Opry.”

His double-bass era finished after five or so years and he went back to electric bass, as a sideman to Canadian singer-songwriter Matthew Good.

In 2017, Midnight Oil reformed and toured globally before heading back into the studio for one final session with Bones, the mini-album The Makarrata Project, released on 30 October 2020. It entered the Australian Charts at No.1 on 7 November 2020, the same day Bones Hillman passed away from cancer in his home in Wisconsin.

The kid from Avondale says on his website: “But me, I’m a simple musician – all I want to do is play my bass, go on tour with new people, maybe get to sit up front with the driver now and again.”

He gave his utmost, by Phil Judd

1978 and I’m back in Auckland after exiting Split Enz due to being stuck in the UK with no money and a young family.

After a couple of months of having decided to chuck in the band caper and wanting to paint seriously, I have a good job at Auckland City Art Gallery. I venture out one Friday night to check out some bands.

I hear Zwines is the place where good things are happening. I’m too shy to go in and mix with the weird middle-class pseudo-punk scene I found in New Zealand ... especially after actually experiencing the gritty working-class UK punk scene. In London we (Split Enz) had for a while stayed on Kings Road directly across the road from Malcolm McLaren’s shop and saw the whole scene unfold ...

So, I stand outside Zwines and listen for a couple of hours. Buster (my old mate from school days) is playing in some band and I’m waiting to check them out. I hear them start playing ... straight away I was struck by the fluidity and finesse of the bass player as well as Buster’s unique drum style. Next day I asked Buster who the bassist was ...

he knew that hard work was the only way, and to do it with a smile onya dial was even better.

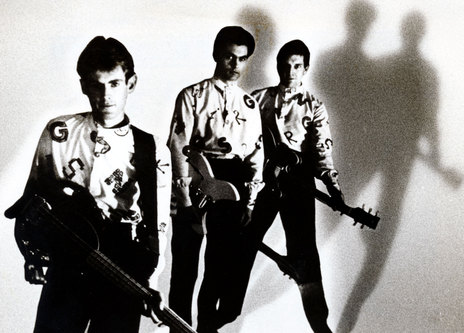

“Bones Hillman” is the reply. By far the best playing and sound I have heard in a long time. It stood out amidst the mediocrity of all the other playing I heard that night. Weeks later, Buster and I start fermenting the idea of having a jam/play together. Bones is into coming along and just jamming. We clicked instantly. He was a spritely 20 and full’a’beans, as was Buster.

When we “got serious” and decided to give it a go as a three-piece, my experience had taught me to prepare well and practise hard with a good repertoire in store. So, for nearly six months we locked ourselves away and practised doggedly. Bones was always a ball of energy ... incredibly fluid and spontaneous bass playing, and, like Buster, full of ideas that were out of the realm of the norm for “punk/rock players” of the time.

Always fun on tour and gave his utmost at every gig without fail. Those Swingers’ practices and gigs of that period were by far the highlight of my band life. We all worked hard and did it all ourselves, the loading in and out ... poster printing and pasting, everything. Bones was never a slacker and gave it his all.

For a relatively naive young Avondale kid he intuitively knew that hard work was the only way, and to do it with a smile onya dial was even better. A wonderful man, a brilliant bass player and lovable to the core.

--

Read more: Bones Hillman remembered