AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

Bernie Griffen

aka Bernie Griffen and the Grifters, Bernie Griffen and the Thin Men

Despite many years performing in bands, it wasn’t until Bernie was in his 50s that he became confident with his own material. Some near-death experiences along the way were hurdles that became opportunities.

There’s a quote I read from Bernie from a couple of years ago where he said, “I think I’m an optimist. There are a lot of things that I’ve survived that other people wouldn’t have. I love being alive.”

This includes an event that took place in late 2016 when Bernie and his partner, writer Kirsten Warner, were on a China Southern Airlines flight heading to London and Germany where they were scheduled to begin a European tour of around 18 to 20 shows.

Bernie, who has always had asthma, had felt a bit flu-ish before the flight. His adult son Joe – who was helping Bernie pack and prepare the house to lease for the four months they were scheduled to be away – actually questioned the wisdom of taking the flight. Bernie took some medication and thought he’d be okay. The last thing he remembers is clicking the seatbelt shut. He actually had pneumonia.

Forty-five minutes north of Brisbane, when the plane was cruising at 30,000 feet, Kirsten knew something was up. Bernie had gone to the bathroom and passed out. Kirsten, who’d followed him, notified the cabin crew when Bernie didn’t emerge, they struggled to get him out. No easy task – Bernie is a big guy. Fortunately, a New Zealand doctor and nurse were on board, the doctor told crew Bernie wouldn’t make it and the plane turned back towards Brisbane. Bernie was put on a breathing machine and kept unconscious, and eventually came around five days later. When he woke, Joe and his partner Veronica were there with Kirsten. The doctors had recommended Kirsten get the kids over to perhaps say goodbye.

Bernie knows he dodged a bullet. Was that an experience that has made him consider his own mortality? “Most definitely. It’s helped calm me down,” he says, laughing.

Bernie turned his brush with mortality into an opportunity.

But as he has done many times before, Bernie turned his brush with mortality into an opportunity. After some recuperative time on the Gold Coast he and Kirsten went to Melbourne where Bernie had lived for a while in the 1970s, and started gathering a following playing open-mic nights (a recurring theme in Bernie’s musical journey). In the process they pulled together the bones of a new band featuring New Zealander Rob Mahoney on bass, Jude Gunson on piano and ska-man Steve Phillips on drums. Bernie and Kirsten had a bunch of new material including a wonderful song called ‘I Fell Out Of The Sky’, inspired by his near-fatal plane experience. While in Melbourne, they recorded a new album, Bernie’s third.

Born in Wellington over six decades ago, Bernie was raised in Johnsonville; it was a Catholic upbringing. There wasn’t a lot of music in the family home, just show tunes and musicals such as South Pacific and The Sound of Music. However, Bernie’s parents did encourage the three children to play an instrument. Young Bernie was also a choirboy: his mother believed that singing would help his breathing. Because of his asthma, as a young kid Bernie was frequently bedridden and it was during one such occasion that hearing Johnny Cash on his radio proved to be something of an epiphany. “Elvis was too nice”. Johnny Cash provided the grit that Bernie loves to this day.

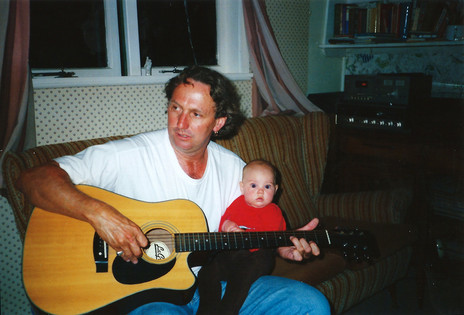

His first instrument at age 10 was an acoustic guitar. He still knows how to play ‘Moon River’. “You never forget how to play the first song you were taught.”

It was at St Patrick’s College – the oldest Catholic boys’ secondary school in the country, a forbidding gothic building looming over the Basin Reserve – that Bernie caught the rock’n’roll fever sweeping the country. One of Bernie’s childhood musical companions was Pat Bleakley who played in BLERTA, Mammal, Rough Justice and Spatz, and was for a time, in the quartet of leading Australian saxophonist Bernie McGann (Bleakley is still an active bass player).

Pat’s parents provided “one of the few places we could make a noise” most Saturday and Sunday afternoons. Bernie was something of a musical loner during those early years, playing folk clubs in Wellington and mixing up a repertoire of covers (Cash, Dylan, Donovan, Cat Stevens, Simon and Garfunkel) and originals. It proved to be a competitive scene. There were a lot of talented players coming up and Bernie concedes it was a difficult time that ultimately bequeathed him an issue with his own confidence and self-esteem. He could never figure out how to be as good as some of those other musicians – especially when one of the other musicians he was working with at the time told Bernie his original material “sucked”. “I believed him.” It may well have been an “off-the-cuff thing to say, hurtful and unnecessary,” says Bernie, “ … nevertheless, if I had a thicker skin or any kind of skin it may not have had the negative effect on my creative life … I took drugs instead. I wanted to shut the world out.”

It wasn’t only that comment that set him on the road to drug addiction. But he remembers the creative wounding as something that prevented him playing publicly, and drugs took him away from himself for a long time.

Bernie took a detour that by 1971 saw him in jail for possession of LSD with intent to supply. A serious offence. It was a time when the New Zealand counterculture was active and, as Bernie says, “It was all part of that period of our lives.”

It was a massive personal spiral to be 19 with cops chasing him all around the country. “It was stupid, obvious and callow … you kind of think you know everything … but it was a time when all the publicity coming out of the States was about Vietnam, rock’n’roll, the Yippies, and I was fascinated by it … I moved to the dark side as often as I could.”

Bernie was sentenced to a year at Witako Prison in Upper Hutt (now known as Rimutaka Prison). “That was the beginning of my education really. It’s kind of interesting that when I went into jail the first few guys who got busted for that stuff clung together and looked after each other … we were a fairly game mob but the reality was that in those days you were treated as second-class citizens even by the crims, which always made me laugh. The thing was, they hadn’t yet discovered how much money could be made from selling drugs. They learnt a lot from us …”

Terry Clark, the Mr. Asia kingpin, was in the same jail. It gets worse: “The last three months of my sentence I was on work parole, going out to work every day. By the time I left prison I had another habit.”

After his release Bernie was put into an alcohol and drug addiction program for treatment in Oakley Hospital in Auckland under the Alcoholism and Drug Addiction Act, passed in 1966. It didn’t work.

By his own admission, Bernie reflects that after his release, things just got worse. He was in trouble way over his head. He ended up back in jail by 1975 for chemist shop burglary and possession. “It was chaotic. I don’t remember being scared. I remember being mad, excited, all sorts of things.”

Bernie’s family did what they could to assist but they didn’t understand addiction. “Dad died in the mid-80s and one of the disappointments of my life is that my father never saw me clean up. He would have been real proud of me. So I wrote that song ‘Put Your Hand of Mine’.

I remember the tears, rolling down my father’s cheeks

as he sat across the table

and said, Boy you gotta stop this thing,

he said, Put your hand in mine

and I will lead you down the line,

put your hand in mine,

everything will turn out fine.

In 1976 Bernie left New Zealand and lived in Melbourne for two years. It was there that he reconnected with music, playing bass. He then became a commercial fisherman for six years on the prawn boats out of Karumba on the Gulf of Carpentaria before returning to New Zealand.

They established Progressive Music Studios, a rehearsal space and recording studio in Anzac Ave.

By this time his parents had moved up to Auckland, so Bernie shifted north, intent on getting his life back on track. It was during this time that he met Terry King and Richard Holden and with some other partners helped raise the money to build a studio by getting five principals to bring in $10K each. They established Progressive Music Studios, a rehearsal space and recording studio in Anzac Ave.

As a result of talking to New Zealand music supporter Brendan Smyth, who was at the time working at the QEII Arts Council (now Creative NZ) they successfully scored a PEP (Project Employment Programme) grant. It paid a wage.

“We carried seven tons of sand up there for insulation between the walls using egg cartons and built the studio. Later we’d do shifts keeping an eye on things. It was good fun and I was playing in the band Gorilla Biscuits with Richard Holden [ex-Terls] and Paul Gilbert on guitar. It was a kind of a hobby for everyone involved in the band. We were pretty good but Paul wanted to play Pink Floyd, Richard was a punk rocker and the drummer, Greg Edwards, was one of those guys who was always pulling away from us. I wasn’t at all sure what I was. We were a bit confused about our songs.”

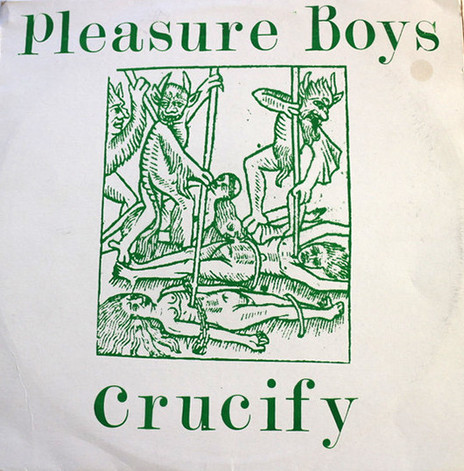

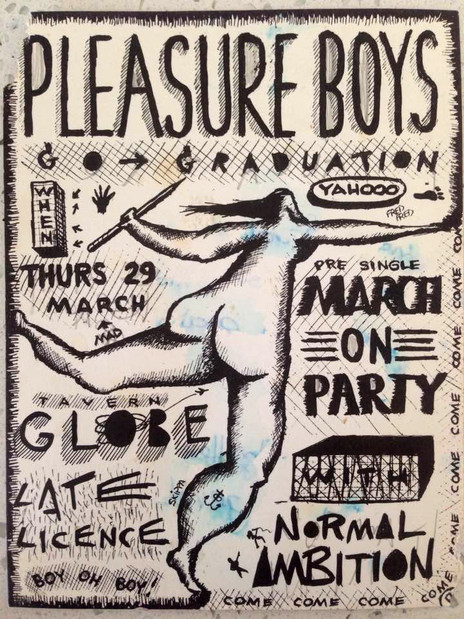

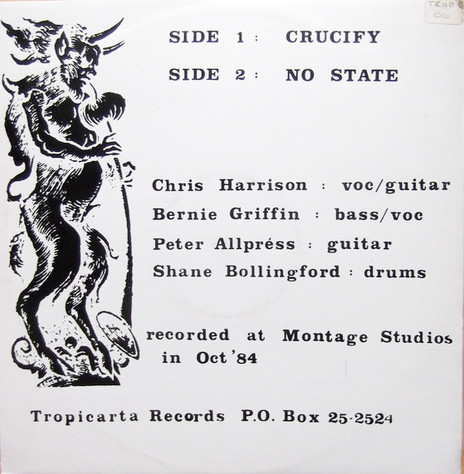

It was at Progressive in 1982 that Bernie heard a band called The Pleasure Boys (all Kings College school friends) rehearsing and joined them playing bass. As he recalls, “I was always a backing guy … pushing quite hard from behind was my memory of it. The music was original, the songs were great, but it was hard getting a recording deal.”

His drug addiction was still an impediment. “I hadn’t come to terms that there was something wrong,” but he was trying to find ways to straighten his life up.

He met his partner, young journalist Kirsten Warner, on New Year’s Eve, 1981. “We were playing at the Esplanade hotel and she was dancing. What a beauty! We’ve been together ever since.”

Bernie concedes he is a very lucky man. He was now determined to follow the road to cleaning up. “Sometimes I look back and I think that the drugs that I took kept me alive … during those periods of deep insecurity, but I paid the price for it.”

In 1987 with his first child, Joseph, on the way, Bernie and Kirsten bought a house (Marcella was born five years later). In 1988 Bernie finally cleaned up. He’d been on a methadone program but he elected to go into residential treatment at Auckland’s Higher Ground Drug Rehabilitation Trust. They kept him for six months, longer than usual but he needed it, and he has been in recovery ever since.

“The thing about recovery is that it speaks for itself. You have to be in recovery, you can’t be recovered, and so I just have to deal with this on a daily basis. It takes a lot of courage to do that… this development lead me to where I want to be and who I want to be … so in 1989 I came out of treatment.”

Bernie never stopped his association with Higher Ground. “I’ve always tried to be of some service because that place helped me so much, so I used to drive the van, take people to meetings and get involved with taking meetings into their house and even as night supervisor looking after them as a job. I have done that off and on for the last 28 years”

In 1991 Bernie started playing solo gigs at the Corner Bar in The Gluepot, at Java Jive Performance Cafe as well as playing open-mic nights, trying out his original material.

As he said in an interview with Graham Reid, “I always covered my fears with alcohol or narcotics, so when I started to write and started doing the songwriter nights, I thought I just had to keep going this time ... and I kept going until I felt better about myself. The belief in myself didn't come from me but from other people. I had to stop listening to the voices in my own head, which was my destructive place.”

In 1995, Bernie met young singer-songwriter Glen Moffatt, who recorded a country album called Somewhere In New Zealand Tonight, produced by Stuart Pearce at Mike Donnelly’s Montage recording studio in Grey Lynn.

He undertook to release Glen’s album, setting up a label, Sun Pacific Records, with Donnelly. It was around the time when alt-country was kicking in. The Warratahs and Al Hunter were building a local audience and visiting artists such as Lucinda Williams, Guy Clark and Townes Van Zandt were touring New Zealand for the first time. They were brought over by a subsidiary of Real Groovy Records, Global Routes Music. The principals included Chris Hart, Kevin Byrt, Marty O’Donnell and Grant McAllum.

On Auckland’s alternative station 95bFM Bernie provided some of the push for the growing acceptance for alt-country with his Border Radio programme, specialising in American roots music.

His immediate priority was to get Glen Moffatt’s album into the record stores.

Having his own radio show has been a crucial vehicle for keeping in touch with the music he loves and testing what an audience likes, as well as providing some degree of personal visibility.

His immediate priority was to get Glen Moffatt’s album into the record stores. Bernie knew it was a good record, so he literally put the stock into his car and drove around the country selling the album. “There was something like over 300 record stores back then, so I drove around the country and sold them Glen’s album to try and get the money back ... it ended up selling about 3500 records which, for an independent label, was a pretty good effort. But what I quickly realised as soon as I started talking to the shop owners, was that I needed more catalogue to build those relationships.”

In 2000 Bernie started building that catalogue by working with small indie labels like Ode Records, as well as approaching some of the major labels (for example BMG, which had an indent label that Bernie thought he could improve sales figures on). When he approached Real Groovy about selling some of their imports, he gleaned more experience by working for the company’s distribution arm Global Routes Music, then became a partner. It resulted in Bernie eventually buying Global Routes off them. It was a brave move but Bernie has always been game. He also put together an offer to EMI. “They wanted someone to sell the product that they couldn’t sell themselves.”

For a couple of years Bernie was running a happening business, but dark clouds were on the horizon. The global record industry was on the cusp of facing a challenge that nearly wiped it out. Napster, LimeWire and illegal file-sharing would ultimately change the entire business forever. Album sales were in decline because legal downloading services such as iTunes (launched by Apple in 2000) unbundled the album and sold individual songs, primarily to drive sales of their lucrative cash cow, the iPod portable media player, which hit the market in 2001. This culminated in global sales of CDs declining by negative increments of 15% per year. Record shops were dropping like flies. Many people in the recording industry saw the writing on the wall.

However, always intent on building a stronger independent label community, Bernie was instrumental in helping set up Independent Music New Zealand (IMNZ), encouraged by Cath Andersen who worked for the NZ Music Commission. The organisation was established to help fund independent music and lobby radio and government for more New Zealand content on air. These days IMNZ also promotes and sponsors the Taite Awards and Going Global music seminars. The belief was that by bonding together, the indies would have more strength to lobby politically and make their presence stronger and “hopefully give them the ability to look into the future with some level of confidence”. Bernie was elected as the first chairperson for IMNZ, a position he held for seven years. It was a positive initiative that Bernie is proud of contributing towards.

As leader of the independents, he sat with the big boys on the board of the Recording Industry Association of New Zealand and the Radio Broadcasters Association, and was a founding board member of the New Zealand Music Commission.

But by 2006 it was almost game over for the distribution business, with only a few CD stores still standing. “Forty percent of revenue went out of the market in 12 months.” In 2008 Bernie elected to put Global Routes into voluntary liquidation. He was seriously ill with stomach ulcers partly as a result of stress and the debilitating concern of considering what to do next.

Pushing the careers of others is frequently all-consuming. Some might say there is no quicker route to agony. Bernie stepped back, diversified his work and income. Working nights again at Higher Ground for eight years gave him quiet time and he began writing songs and exploring his own creativity. He continues to work tremendously hard at building a career for himself when others his age are contemplating some form of retirement.

Over the years building his Flaming Pearl record label and Global Routes Distribution, Bernie built a positive personal reputation working with local artists. He had also figured out how building a community, promotion and social networking should be applied. Bernie may have been an old dog, but he was a far smarter dog, having seen the business from both sides.

By now, on the other side of the business, he had assembled a bunch of original songs that were confirming a talent that he was never quite sure he possessed. Many of those songs were written for his two children. “I’d sit in the hallway between their bedrooms and sing these songs to my kids before they went to sleep. They were songs about my life and the various places where we had lived, New Zealand stories.”

It was at open-mic nights and at singer-songwriter groups alongside his peers such as Donna Dean and Al Hunter that Bernie finally started to receive positive personal feedback.

Other musicians like drummer Bud Hooper helped Bernie build his self esteem by saying, “You gotta record those songs mate. They’re incredible.” Songs such as ‘South West Gale’, which Bernie sang at a friend’s funeral, were helping Bernie establish some self-belief.

In an interview I did with Bernie for Radio New Zealand in 2014 Bernie said: “I challenged myself and I felt so naked playing in those places … one of the things about being a drug addict is you have very low self esteem so I never thought that what I had to offer was worth anything. When I stepped forward I felt the full exposure of that, so doing those songwriting nights was just really important for me cos, slowly, I got a new suit of clothes. I went from naked to a semi-transparent Indian suit to a full suit of armor and only then did I start to realise I had something to offer.”

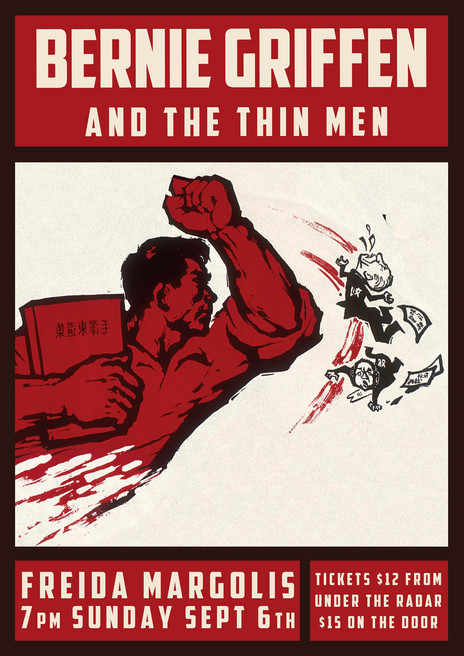

All Bernie needed was a band. He needed players who could sonically do justice to his growing catalogue of originals. As often happens, he didn’t actively go out looking for a new band. Word of mouth and serendipity brought players to him.

Bernie reconnected with a younger musician, Tony Daunt aka Tony Dee, whom he had met during the Progressive Music Studio days. Bernie proposed to him that they get together and play some music. That was the bass player sorted. He became the first of the band that would eventually morph into The Grifters, a name inspired by the hard-boiled American crime novel written by Jim Thompson. Bernie is a voracious reader.

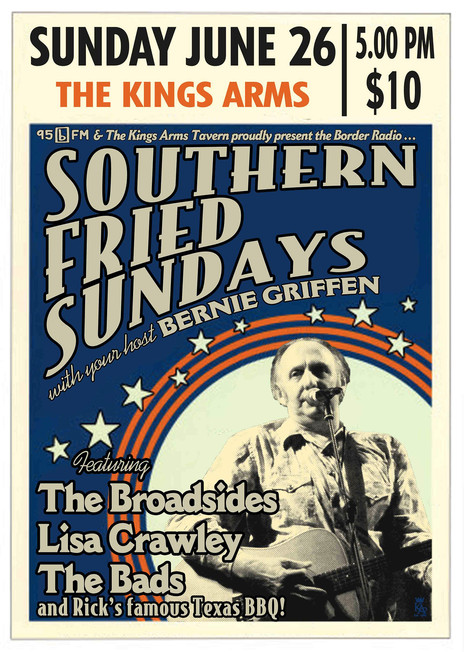

Bernie was creating his own gigs by running shows such as Southern Fried Sundays at the Kings Arms Tavern.

The next musician to join was guitarist Steve Roach, formerly a member of Techtones who were active in the early 80s, although Roach hadn’t been playing live much since that time. The personal chemistry and Steve’s lateral sonic guitar tones were a perfect complement to the Grifters’ original sound and development. Drummer Kerry Fraser was enlisted and suddenly Bernie had a solid band that could give a life to his songs.

Bernie was creating his own gigs by running shows such as Southern Fried Sundays at the Kings Arms Tavern. “You had to (run your own gigs). I was nearly 60. Nobody is going to offer you a show.” One night he met Dave Khan, described by music blogger Graham Reid as “ridiculously talented, he is a modest presence on stage that can set the air alight with seemingly effortless playing, he also turns down the moods for hush-now intimacy. Or he can come off as a folk-rock firebrand.”

Khan later worked with Marlon Williams, Tim Finn, The Bads, Tami Neilson, Delaney Davidson, Gin Wigmore and Don McGlashan. But at the time Dave was playing in The Broadsides, whom Bernie had booked for a gig at the Kings Arms. Dave asked Bernie if he could have a jam with The Grifters.

Bernie Griffen and The Grifters was now a fully formed band, although Bernie concedes that he was never comfortable with his name in lights. “It scared the shit out of me having my name out there at first … it makes you a target for almost everything … but the band members’ response was, ‘what’s wrong with Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds?’ You can’t argue with that, can you?”

One of the focal points of their repertoire was Bernie’s composition, ‘29 Diamonds’. “That song was a gift,” says Bernie, “it arrived virtually fully formed as a result of reading the newspaper headline.”

In an Under The Radar interview in 2012, Bernie said that ‘29 Diamonds’ was written “to document the terrible fire in the Pike River mine. I have spent a lot of my life in dangerous places earning a living and felt strong empathy towards the families who were suffering. There is a long history of songwriting in folk music about the powerlessness and exploitation of miners by mine owners. I was sure, right from the beginning, that all the owners wanted was for the problem to disappear and not cost them too much. And so it proved, which is the history of these disasters and general corporate neglect. There is really no recourse for the families, mothers, fathers, sons and daughters of the local people. It was so sad. The only thing I had to offer was perhaps a little money and my meager talent as a songwriter. As I was writing the song I thought I would try to keep the emotions I felt on the surface and the lyrics simple and easy to understand. As I was writing I read the story about one of the families having a baby shortly afterwards and that moment of hope and rebirth became the last verse. Also, it is a tribute to the spirit of the people of the West Coast and to the souls of all miners.”

The band organised some cheap recording time at MAINZ, a faculty of Tai Poutini Polytechnic in Auckland. With engineer Lance Powell they recorded an EP of five songs, including ‘29 Diamonds’. It was no frills, but Bernie doesn’t suit frills. What you see is what you get. The other songs recorded that day included ‘Hand In Mine’, ‘Southwest Gale’, ‘Friday Night’ and ‘Horse Song’ (written one New Year’s Eve, back when Bernie was a commercial fisherman, while sitting in the wheelhouse of his trawler in the Auckland Islands). This selection of songs cemented his self-belief. In fact, he regrets that they didn’t push ahead and record an entire album.

The second EP was produced by Karl Steven (ex-Supergroove). Bernie had shared a few shows with Steven’s band Heart Attack Alley and he valued Karl’s involvement. They recorded the second EP, which included the songs ‘Sometimes I Feel So Sad’, ‘Take the Money’, Hurricane’, ‘Dangerous Engines’, and ‘Reef of Dreams’. The second EP was never a physical release but eventually saw the light of day when the two EPs were made into the Grifters’ first album Everything So Far, released in 2012.

However, internal friction was starting to unsettle the band. Bernie concedes, “I had an idea of where I wanted to go which was slightly different from somebody else’s idea … and that becomes an argument.”

Growing word of mouth attracted sufficient attention to see Bernie Griffen and The Grifters supporting a number of international acts.

Dave Khan and Bernie were working together putting on the shows called The Gunslingers Ball. These gigs were hugely successful and, as it’s stated on Bernie’s website, they “grew in just a few years from the occasional evening of country-fried revelry to what the NZ Herald described as a full blown ‘wild musical feast [of] alt-country, cowboy, punk, folk and country blues bands’. This definitely wasn’t your nana’s hoedown. Straddling the divide between heartfelt alt-country, raucous blues, rockabilly brashness and punk bristle, the Gunslingers Ball melted musical barriers to the point where there were none.” Bernie still believes he let what could have been a successful brand go begging. “It should have been a lot bigger than all of us.”

Growing word of mouth attracted sufficient attention to see Bernie Griffen and The Grifters supporting a number of international acts, including Emmylou Harris at Vector Arena, Little Band of Gold (twice), Justin Townes Earle, Eilen Jewell, and Kitty, Daisy and Lewis.

But that momentum wasn’t enough to stop The Grifters breaking up. Bernie is sage enough to not fan any further flames of dissent. Suffice to say he is extraordinarily thankful for the support that line-up gave him, as well as having musical and creative respect for each and every member.

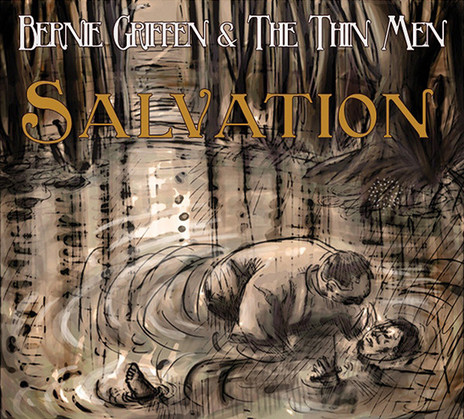

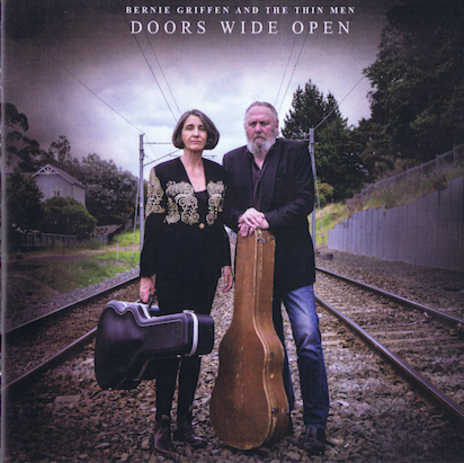

Bernie had formed a band called The Flaming Pearls, consisting of Bernie, Kirsten, Janek “Buck” Croydon on pedal steel, Louise Evans on fiddle, Noel Ward on bass and various drummers. But to record the second album, Salvation, in 2014 at The Lab recording studio, Bernie, with Kirsten Warner and Steve Roach, used a session band. The line-up included Bernie, former Pluto and Nightchoir members Mike Hall (bass) and Matthias Jordan (keyboards) and Chris O’Connor (The Phoenix Foundation, SJD, Don McGlashan and the Seven Sisters) on drums. The album was produced by Jol Mulholland.

They recorded 11 songs pretty much live in 11 hours, over two days. The mix took a bit longer but the result was a more cohesive sounding effort, albeit a bit darker and rockier than the first album.

It’s an album that reflects Bernie’s considerable life experience. Andrew Baker from Witchdoctor reviewed the album succinctly when he wrote: “While at times rather sombre, Salvation never depresses; there’s light in the mire and the music that complements Griffen’s rumpled musings with a kind of hopefulness. Gritty, dark and raw, just like life itself, this is a record to be proud of – for musician and listener alike.”

For Bernie, making Salvation was “really intense, exciting and scary. I was really pushing myself to get this stuff done. It was pretty much first take – I only re-sang one of the songs.”

Capitalising on the reputation of Bernie’s long running Sunday night radio show, talented young director Tom Levesque initiated a successful crowd funding campaign to produce a music video for Bernie’s song ‘Burial Ground’, co-written with Dave Khan.

In the blurb accompanying the crowdfunding campaign: “It’s a song with deeply personal roots – a story about revenge, mortality and rebirth – the vision for the music video featuring dramatic New Zealand landscapes, tells the story of a drifter dragging a coffin across the Hauraki Plains, towards a brutal conclusion of fate.”

It reads like a 21st century rewrite of Blind Willie Johnson’s ‘Dark Was The Night, Cold Was The Ground’… and that’s dark.

As Bernie said, he’s “no spring chicken and has no time to lose” in fulfilling his vision of performing overseas and connecting with fans beyond New Zealand.

In many respects Bernie’s recording process is similar to his creative process. He has a guitar next to his chair that he strums while watching TV. Tunes often come that way but then the lyrics demand more attention. The lyrics have to mean something and are frequently autobiographical. “You have to own your life.” His years in a 12-step programme with other recovering addicts has helped him articulate lyrics about heartache and heroism. “I’ve been clean for 28 years … I don’t have to be anything in that place. I just have to be myself and people take hope from that.” As Bob Dylan once famously said, “to live outside the law, you must be honest.”

Bernie’s composition ‘The Girl With The Golden Arm’ is about somebody he knew and thought had died in Sydney. “I recorded the song about this woman who was such a good friend of mine and then she turned up and I had to change the words because I’d used her name in the song … that was an incredible experience for this woman to come back and to be in recovery after being on methadone for 35 years ... I played her the song ... she was sitting on our couch and she sat there and wept silently.”

‘Circus Song’, co-written by Bernie and Kirsten, is very Bertolt Brecht. As Kirsten says, “Brecht informed my roots ... again, it’s a song that refers to that life of being on the edge and it’s about addiction as well … the constant loss and longing.”

I asked Bernie if, as he progresses through his sixth decade, whether his sense of mortality informs his legacy and what he is leaving behind. He responds with an emphatic “Yeah! I’m probably the most secure I’ve ever been in my life. Financially, in my relationship with Kirsten and the kids, the things that I do and think and behave … I’ve learned an enormous amount over the last 10 years about being in bands because one of the things that I miss is being in that community where there’s four or five people whose opinions do count, you know … cos quite often it’s just my opinion and if that’s the case nothing really changes … it’s really important that I keep my mouth shut for once and listen to what’s being said and ask the important questions … but only ask them once.”

While Bernie was in Australia recuperating from his near-fatal experience, he and Kirsten recorded his third album. Although she sang backing on the other two albums, this was her big step forward. Bernie has encouraged her to learn to sing and play guitar and brought her into the music so they can move forward together with it. Their collaboration has become central to his music and career.

Bernie still considers he doesn’t have a body of work. But it’s not a question of quantity. It’s about what the artist becomes from his or her creativity and Bernie has become the man he always wanted to be, albeit at this late stage in his life. “You gotta finish strong. You’ve gotta play as much as possible cos there’s not that much time left.”

I’m not sure who said it, but self-belief and sheer dogged tenacity are just as important as any kind of creative ability. Creativity is littered with talented people who gave up, but Bernie won’t!

At the 2019 Taite Music Prize, Bernie Griffen was awarded the debut Independent Spirit Award in recognition of “a New Zealand person who assists our musicians to grow and find their own unique pathways”. The award, which was presented by Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern, acknowledged his work a founding member of Independent Music New Zealand (IMNZ), the group behind the Taite, and served as its first chairman. For many years he has acted as a mentor and sounding board for independent artists.

Bernie Griffen, lifelong stalwart of New Zealand music, and mentor to so many, passed away in August 2023.

--

Read Bernie Griffen, up against the wall – posters of grifters and gunslingers

Flaming Pearl Records

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air