Winter, 1986 - Dalvanius Maui Prime insists a Rip It Up writer visits Hāwera and Pātea so he can explain his philosophy about te reo.

It’s another Saturday night at the Papatoetoe Inn. On the tiny stage is Dalvanius, up from Hāwera on the bus for two nights with the resident band. The bar is comfortably full, and the musicians seem very casual, though there’s some snappy playing going on beneath Dalvanius’s delicate and heartfelt renditions of soul favourites. It’s an easy atmosphere, the crowd singing along and dancing cheek to cheek, and after finishing his short set, Dalvanius remains to mingle.

Strangers and old friends chat with equal ease about a recent TV appearance or news of acquaintances from other parts of the country. At the same time though, Dalvanius is planning ahead. He’s supposed to be in Wellington on Monday to work on a soundtrack. But just before he went on he heard an aunt has died back in Pātea, and he must return for the tangi, which will last until Tuesday. So if we’re to talk about the Pātea Māori Club, their new album, their town, and Dalvanius’s philosophies, plans and dreams, Rip It Up must come too.

Auckland is still asleep when the bus pulls out at 8am the next day. But ensconced in the back seat, Dalvanius is alive with ideas and anecdotes. The up and ups of the past three years could scarcely have been imagined, but there are plenty more dreams where they came from to come true yet.

One doesn’t have to look too far to see the impact that’s been achieved. In Hamilton, kids are twirling poi in the bus depot. In Te Kūiti, a mother brings forward her children who want to shake Dalvanius’s hand: on the bus wide-eyed 10-year-olds ask for autographs.

“The whole thing is the language,” he begins. “To reach a young audience with the Māori language, without compromising the language. Through that, the kids gain self-esteem and the Māori language and culture survives. That’s the whole point of the experience.”

The story beings in Tokomaru Bay on the East Coast, when Dalvanius – flush with the success of his production of Prince Tui Teka’s 1982 hit ‘E Ipo’ – went to meet Ngoi Pēwhairangi, an elderly woman greatly respected for her songwriting and efforts to keep the language alive. She asked him, ‘Do you write any songs?’ Only in English, he had to reply: I don’t speak Māori properly.

Pēwhairangi said, “How can we get the Māori language heard and accepted by the younger generation?”

The answer was through the music. “Let me be your voice – you can be the tune,” said Pēwhairangi. Dalvanius extended his two-hour visit, and within three weeks the pair had written 18 songs. Among them was a contemporary poi dance, with lyrics in Māori, but aimed at the mass market.

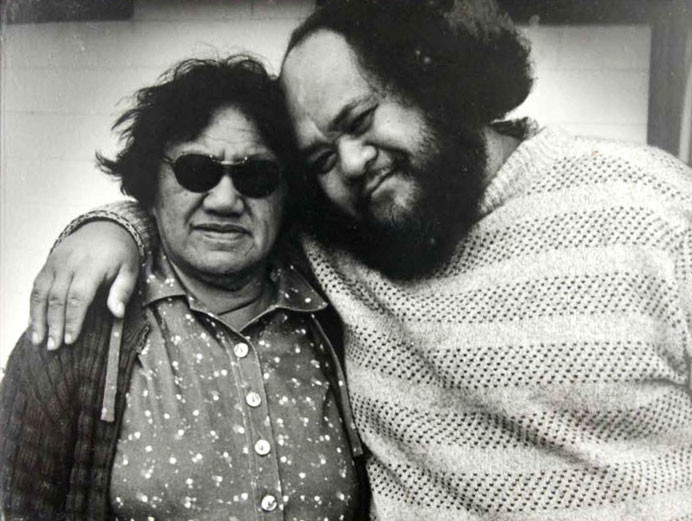

Dalvanius with Ngoi Pēwhairangi

“‘Poi E’ was not a fluke – it was all planned,” says Dalvanius. “There were a lot of issues we wanted to highlight in the Māori's place in the New Zealand social structure. Many people had been looking for reasons and answers, but they’d never thought of using the kids’ leisure to put across their message.” The songs having been written, were then given a top-class production by Dalvanius with musicians (“who shared the same vision”) such as Stuart Pearce, Gordon Joll and Alastair Riddell. “I wanted to get rid of every reason radio had for not playing the records.”

Enter the South Taranaki Cultural Group, a traditional singing group from Dalvanius’s hometown of Pātea, a small community suffering from the closure of the local freezing works. They became the Pātea Māori Club (after the then-popular Culture Club and Tom Tom Club) … “I wanted to use the song to uplift the community.” Unable to get any grants or funding – reserved to projects of a more traditional nature – Dalvanius went to local businesses. Twenty-seven of them donated $100 each, and ‘Poi E’ was under way.

But for the record to come out, it had to have someone to put it out. No record label, including the independents, was interested. “I had a No. 1 hit with ‘E Ipo’, a No. 3 with ‘Maoris on 45’. I thought I had credibility,” says Dalvanius. “They all said no. I was so upset and uptight. One company said, throw in a couple of Pākehā verses, like ‘E Ipo’. But I didn’t want to compromise the Māori language. Ngoi said, start your own company, but I had doubts.

“I envisaged a Māori Motown, with a roster of acts starting with the Tama Band, Taste of Bounty, and the Pātea Māori Club. The name of the label had to have a young image. I chose Maui, after the character in the legends: a hero to all Polynesian races. I wanted our kids to have a mega Māori hero.”

The images on this page of the recording of Poi-E, with Dalvanius and co-producer/engineer Dave Hurley and The Patea Māori Club are courtesy of Sue May.

Getting the video made was another problem. Money from a fund for “Māori interest” programmes was denied ‘Poi E’ because, says Dalvanius, it wasn’t sung in English. But money was provided for videos for the Tama Band and Taste of Bounty. So Dalvanius talked a video maker into making three videos for the price of two. “I had the last laugh,” he says with a grin. But getting it aired was yet another obstacle. There seemed to be no slot willing to show it until Derek Fox placed the video on Te Karere. It was then used as a time filler, sales began to pick up for the slowly moving record, it was placed on Ready to Roll, and then things snowballed … and the criticisms began.

Ngoi had been reluctant about the mix of traditional and contemporary cultures, but gave Dalvanius artistic control. He recalls her saying, “Oh well, if that’s the way you’re hearing it, that’s the way it should be.”

Dalvanius: “There’s a strong section of Māoridom against things that are new. I knew I’d get up their noses, especially if Ngoi thought that, and I was right.

“The whole idea of the video was to show the transition of Māori cultural groups from the pā to the city. I wanted to highlight that we were survivors, and the main survivor was the language. Even though we had taken Māori music to another sphere, the language was unchanged.

“I got letters galore and phone calls from Māori fundamentalists (I like calling them fundamentalists). The hardest thing was getting knocked by my own people. So I locked myself away in Hāwera. Ngoi didn’t like the video – it was too way out for her. The whole idea of it was to show the evolutionary growth of the Māori, the political and economic growth. Ngoi changed her mind. She rang me up and said, ‘I see what you were saying. All my grandchildren are bopping to ‘Poi E’!’”

As ‘Poi E’ broke, Dalvanius was in Europe, at the Midem music festival, where overseas companies showed keen interest in what the Pātea Māori Club was doing. When he came home, two reporters were waiting for him at the airport. “‘Do you know you’re No. 1?’ they asked. It freaked me out!”

“‘Poi E’ had an incredible effect on the community,” says Dalvanius. “It brought the town really close together. The Pātea Māori Club is their pride and joy.” All proceeds from the Club go into the Pātea Cultural Trust, “one niche of the revitalisation of the community.”

Three years after the closing of the Pātea freezing works, and the ghost-town predictions that went with it, the event is now seen in a positive light. “The closing of the works made us go back to what we’re good at – living off the land.”

The Rangitawhi Trust is a key element in the striving towards self-sufficiency. Formed four years ago with the amalgamation of nine local marae, the trust has created jobs by making use of government work scheme (which, among other things, helped upgrade rundown marae) and is now establishing long-term employment in horticulture, meat processing and other activities. The trust is a also a centre for counselling and social work, and its office in the main street of Pātea is where the Pātea Māori Club’s activities are organised.

“For a start, there was a really dull atmosphere after the works closed,” says trust manager Nick Pirikahu. “People didn’t know where to turn to. We’ve been able to pull ourselves out of that vacuum and achieve self-determination and pride. We made submissions to the government saying, these PEP schemes are a waste of time and money. Give us funding, and we’ll create long-term employment.

“The community has become stronger since the closer. When the works were open, people were individuals. With no money, people pool their resources. It’s been tough, but they’ve learnt to accept it. People had to stay here, this is their tūrangawaewae … a bonus of the closure has been the teaching of our culture: taha Māori. Knowing how you are and where you come from, knowing your whakapapa, gives you purpose and pride.”

The proudest moments for Pātea have been the two overseas trips the club has made, touring Britain and the United States, plus a royal command performance in Edinburgh. With excellent groundwork by their UK record company Sonnet, the Pātea Māori Club was feted on its travels. Audiences loved their shows, they performed on television 12 times in a week, in the House of Commons, at a Nelson Mandela benefit with many black acts, and even busked at Covent Garden.

NME made ‘Poi E’ single of the week, and BBC’s Radio One playlisted it. “Getting it on high rotate is the secret, but we didn’t have the right video. I wanted to make a video showing clips of Prince Charles and the Beatles all swinging poi. It would have taken off in Britain. We asked Buckingham Palace for permission: Yes! We asked Paul McCartney: Yes! But TVNZ wouldn’t let us use the film. What’s their function? Who are they supporting?”

Dalvanius met Ken Livingston, chairman of the Greater London Council (now dissolved by PM Margaret Thatcher) and observed the support the GLC’s Ethnic Minorities Group gave to community cultural ventures. A visit to the Brent Black Music Cooperative in London, a training centre for musicians with a heavy emphasis on reggae, further fired Dalvanius’s dreams of creating employment out of music and traditional culture.

In America, the club was given a lot of assistance by the Violent Femmes. They played together at the cult venue Irving Plaza, and the Femmes made sure the right critics were there. The club performed for New Zealanders new ambassador to the US, Bill Rowling, and after Kool and the Gang at Disneyland’s 30th-anniversary celebrations.

Before the first concert in London, however, Dalvanius received news that Ngoi Pēwhairangi had died. “I cracked up. I wanted to come home,” he says. “But she would have murdered me if I had. Ngoi, a woman from another tribe, had blessed me. Part of my life is dedicated to carry on her work. I found my Māori soul through Ngoi.”

One of Ngoi’s dreams, shared by Dalvanius, is for a national cultural group, made up of members of all tribes, with in-house training for its young members along the lines of the Bolshoi Ballet – and financed along the lines of the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra, the “epitome of monoculturalism. The New Zealand government is happy to use Māori culture to welcome overseas guests, but we won’t fund it effectively.”

Essential to the preservation of the culture and language is the establishment of a Māori radio network to counter the damage done by the disinterest, token gestures, or just plain racism of New Zealand’s radio establishment. “Radio is embarrassed by the Māori language,” says Dalvanius. “They say that Pākehā don’t want to hear it, we’ll we’ve proved that’s garbage.” The importance of radio is hit home when Dalvanius visits an elderly relative in Pātea, confined to bed and listening to the opening of Te Māori broadcast from Wellington (on Access Radio, naturally). She is elated to hear her own language on her radio.

But Dalvanius is not one to blame the Pākehā for everything. He regrets the lack of solidarity in Māoridom, and the handicap of tribal differences. “Māori should have total control of their destinies. Should the state provide everything? No. We should tap our own resources and capitalise on them. But that’s not to say we don’t hold our hand out for our share at the same time.”

“Are young Māori prepared or able to take their place of their elders?”

Dalvanius describes the Pātea Māori Club LP as a concept album, with six songs on it being from the musical that is “stage three” of his artistic master plan. Called Raukura, the concept side begins with ‘Ko Aotea’, a chant about the canoe which sailed from Hawaiiki, bringing the Māori to Aotearoa. ‘Taranaki Patere’ is a pan-tribal history of the migration, mentioning all the canoes. ‘Nga Ohaki’ mourns that the elders are dying. “Are young Māori prepared or able to take their place?” While the emphasis on this side is on the traditional, adepted with contemporary sounds, ‘Ngakau Maru’ is a blues/love song.

With ‘Haere Ra’, Dalvanius wanted to pay tribute to Ngoi Pēwhairangi, saying “return to your ancestors”. “It includes a reprise of ‘He Konei Ra’ and a taped excerpt of Ngoi saying we have to make today work for us.” It’s one of the few occasions she was recorded speaking in English.

Side two is the dance side. It opens with an introduction by a black DJ from New York before ‘E Papa’, the reggaefied Māori stick game song. More New York influence can be heard on ‘Kōhanga Reo Rap’. “The kids were fired up by what they saw in New York. The lyrics are a collection of catchphrases in Māori about their lifestyle.” It’s designed for use in the kōhanga reo classes. The record is completed with ‘Poi E’, ‘Aku Raukura’ and ‘He Tangata Tini Hanga’, an action song about a macho man-about-town.

The opening track features a traditional Māori flute, played by an elder, Joe Malcom. Also playing on the album are Fred Faleauto and Dilworth Karaka from Herbs, Mike Farrell, Stuart Pearce, Gordon Joll, Brian Glamuzina and Willie Dayson.

In November, the Pātea Māori Club goes to Australia to perform, and next year is another major work tour. They’ll perform in Asia, the United States and Britain, with the tour climaxing at the Edinburgh festival. (Speaking of festivals, Dalvanius digresses: where were the Māori and Polynesian acts at this year’s Wellington festival?) Before Christmas there will be a New Zealand tour, and a television special is being filmed for broadcast in Australia and the US (“It will probably never be seen here”); the film will include footage of critics of ‘Poi E’.

“The Pātea Māori Club is not the be-all-and-end-all of Māori music,” says Dalvanius. “We’re just one niche, we hope: a base to build on. People who say, oh it’s a fluke … it’s not. It’s planned, marketed. We’re marketing the Māori language. The Pātea Māori Club is just a vehicle by which the language can be heard.”

Through the survival of the language comes self-esteem, pride and, significantly, employment. “The Pātea Māori Club is just stage one of a five-year plan.” Apart from the cultural trust and other music groups Dalvanius hopes to establish, there are the many schemes and dreams he has for the “Maui empire” – to be based, naturally, in Hāwera and Pātea.

“If anyone thinks there was money in ‘Poi E’, they can look at this car,” says Dalvanius of his rusty, damp Valiant. “Everything goes back into the collective.” Visiting the Pariroa marae near Pātea, he says, “The success of the Pātea Māori Club has worked because I’m engulfed in traditional Māori culture. We live it, we’re not just weekend Māori. In my childhood, this marae was the hub of life. We grew vegetables here, swam in the swimming hole, caught freshwater crays and eels, it even had its own store.”

It’s a living culture, and a living language – and both are being revitalised by initiatives such as the Pātea Māori Club and dynamos like Dalvanius. On the way out of Hāwera is a symbol of the rebirth. The old home of Hāwera’s other great communicator, Ronald Hugh Morrieson, is now a kōhanga reo centre for teaching the Māori language to a new generation.

--

First published in Rip It Up, September 1986. The headline means “When the language is secure, the status of the people will rise and the land will be safe.”