Paul Casserly is most comfortable behind-the-scenes in all his media guises, but it’s his foray into music that has nudged him, however unwillingly, into the limelight. Along with Strawpeople co-founder Mark Tierney, key collaborators such as Greg Johnson, Fiona McDonald, and an array of top vocalists and musicians, he has created some of our smartest pop music.

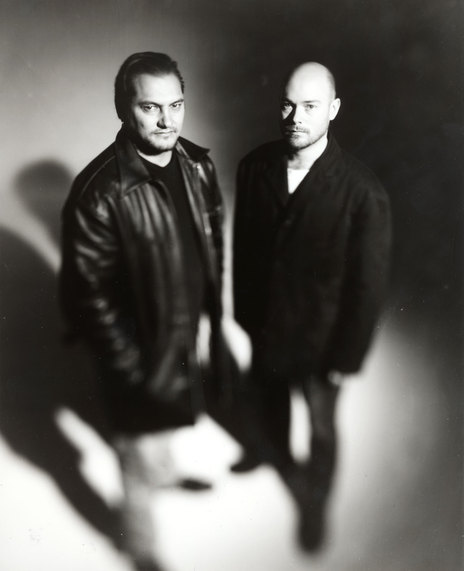

Strawpeople - Mark Tierney and Paul Casserly.

Media, in all its forms, is in Casserly’s blood – he’s an award-winning television producer (Eating Media Lunch, Havoc and Newsboy and others), and a prominent critic and writer on media. He’s also been a director, jingle writer, DJ, magazine editor, video maker (Tim Finn, Crowded House, Dave Dobbyn among others), radio commentator and voice-over artist. With Greg Johnson, Casserly even gave the Shortland Street theme a make-over in the late 90s.

In many ways Strawpeople were ahead of their time. They were one of the first local artists for whom the studio became an instrument. Although Strawpeople would never “make it” overseas (despite strong international interest and high profile movie synchs – Gus Van Sant used ‘Wings of Desire’ in a crucial scene in his 1995 film To Die For) their influence can be felt on a host of studio-based acts which came in their wake. And unlike many of their contemporaries, their records still sound great today.

“You could remaster most of the Broadcast era, with a pinch of Worldservice, put three younger, cooler people on the artwork and release it to positive reviews today,” says Tierney. “If you add in one or two from Vicarious, it’s a global hit.”

Strawpeople featuring Victoria Kelly - Beautiful Skin (1995)

Casserly himself has managed to keep a low public profile and in many ways that has led to Strawpeople’s legacy being under-appreciated. “I don’t have the skills required to be up front,” Casserly told the NZ Herald’s Russell Baillie in 2004.

“And so I recognise where my talents lie and it’s definitely backstage, and when it comes to music I don’t play an instrument and I don’t sing, so that’s pretty clear. The same with TV stuff. I can get by on radio but it’s a different skill to get by on television. I’m not a show pony, as such.

“I’m not really musical. I don’t know how to make music in a traditional way. I get people in to do the music and I direct what they do, really. But then I usually spend about a year working on my own. I can be a bit of a hermit.”

The early days

A fascination with sound and its manipulation was evident early, with Casserly telling RNZ in 2018, “I was sampling things before we had a sampler. I remember in the late 70s my Mum had a tape of the Pope and I’d have Public Image in one channel of the tape deck and the Pope in the other.”

But the Strawpeople story starts in the cramped studios of Auckland’s bFM in the late 80s.

It was a place where Casserly, who struggled with his studies, found a bunch of likeminded geeks and outsiders. One of these was Mark Tierney who ran its tiny 8-track studio.

“I was lucky in that I joined just as the station switched from AM to FM and they upgraded the suite from the 4-track in a closet situation to 8-track, and with a real honest-to-god mix console,” remembers Tierney.

“We were still using spring reverb though which is hilarious to think about in 2018. So I spent most of 1984-88 living there – I often used to sleep in it – desperately trying to make interesting noises happen. Paul brought a sort of focus to the enterprise.”

“The main thing in those days,” say Casserly, “was that we just loved hanging out in the studio and making stuff and, both being DJs at bFM, we had brilliant access to all sorts of music.

“I think the specialist shows like Audible World gave us a sort of degree course in music.

“We were lucky to be doing things with low tech that, thanks to Mark’s skills, sounded pretty cutting edge. He was obsessed with all that, especially the high-end Fairlight stuff that was worth hundreds of thousands, he studied that shit intensely and he number-eight wired it at bFM’s studio, making two non-musicians sound like we were on to something. Kids have better tech on their phones today!”

Tierney remembers the first collaborations were proto songs of ‘Something Else Is Missing’ (the above-mentioned track featuring the Pope) and another using BBC coverage about Chilean leader Salvador Allende.

For a while the pair worked at a restaurant together and would go to the studio afterwards to make music, getting home at 5am.

Tierney: “We were both poor, frustrated musicians – Paul was a decent drummer and had been in a ska band, I was a terrible keyboard player who used to make weird noises with a Korg MS-10 – that were interested in the same politics and popular culture. The recording studio at bFM was heaven for me.”

Strawpeople - Paul Casserly, Mark Tierney, Stephanie Tauevihi.

Both were inspired by the cut-up work of Coldcut and the Bomb Squad.

“We had zero access to music gear,” says Tierney. “To make the beats we would borrow whatever drum machines or synths we could get a hold of. If we were flush that week we would rent one. That was the big time.

“I distinctly remember driving our flatmates nuts by playing a six-minute loop of a 909 drumbeat for several hours after we had come out of the studio at 4am.”

At the time they called themselves Red, which they soon had to change after a certain band from Birmingham became popular.

That Tierney and Casserly would become musical partners shouldn’t have surprised anyone.

Tierney had dropped out of art school and also had wide-ranging media interests and skills: he too would juggle roles as a filmmaker, jingle writer, record producer, commercial director, film critic and tv presenter (on TVNZ’s short-lived music show CV). He is now resident in the United States where he works in the film industry.

Their working process was fluid. “Mark was all over the tech,” says Casserly.

“He pushed the old bFM 8-track to its limits and synched it with drum machines and so on, he figured out how to work around the low techness of it all to get what was at that time an impressive sound. But we both riffed on lyrics and ideas for tracks, Mark was a genius at creating and manipulating samples, that’s where all the early tracks started.”

Both would bring ideas for pieces: some random audio, a possible sample, a beat or a four-bar composed loop, and set to work.

“This process was completely elastic,” says Tierney, “and for some things, almost infinite! I don’t think it’s unfair to describe it as sculpting a song. Both of us would be plonking away, often Paul at the drum machine or synth, me at the console, until something exciting happened. Then we’d swap. It was as genuinely creatively open as you could get.

“Later, as we had more money and better equipment, we’d often get our individual ideas to quite a developed place then start the sculpting process which by that point was two producers producing each other.

“When we recorded and mixed I was pretty much in charge of the engineering, but we both manned the faders. We definitely had some mixes improve by Paul getting bored with me futzing on the console and start playing with the delay or harmoniser and something cool happening. I’m a huge fan of happy accidents.”

Tierney recalls an appearance at a film festival at University of Auckland in the late 80s.

“We did a ‘live soundtrack’ to Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. Greg Johnson and two other musicians on one side of the screen, and Paul and I with very basic synths and samplers on the other. Total improv in the key of G. It was amazing, and the apotheosis of that version of the band.”

Hemisphere (1991)

Their work soon caught the ear of Trevor Reekie at Pagan Records and the pair found themselves the recipients of a QEII Arts Council grant. They signed with Pagan in 1988 and named themselves after a B-grade horror movie, The Wicker Man.

Strawpeople - Hemisphere, 1991

Says Tierney, “The name came out of Paul always wanting to be in a band with ‘people’ in the title, and we both loved The Wicker Man, but Wickerpeople sounded silly to us. For some reason Strawpeople didn’t.

“We did have the advantage of learning from the ‘proper’ musicians we had started recording and producing, like the very early Greg Johnson stuff.” Tierney would later produce Greg Johnson’s breakthrough track ‘Isabelle’.

“From working with him we started to get the idea of how you wrote a pop song. We still didn’t really think it was our bag at the time, we were aiming more for the art gallery/installation vibe, but now we began to get the process.”

The Hemisphere album, recorded at the tiny bFM studio, was released in 1991 and picked up the Best Engineering and Most Promising Artist awards at the New Zealand Music Awards.

It was Reekie who suggested Merenia, a 16-year-old newcomer from Whakatane, who had released her debut single ‘Confessions’ a year before, to sing a remake of The Swingers’ twitchy guitar classic ‘One Good Reason’.

Stamp magazine, July 1990.

Strawpeople recast it as funky, sensual pop. Although it didn’t chart, the song had strong airplay and showed what the duo were capable of.

“Trevor definitely had that old school A&R thing,” says Casserly. “He’s a guru really. Paul Ellis, who stole us over to Sony, also had that thing as did Malcolm Black, but Trevor is in a class of his own. I don’t think we would have done anything if it hadn’t been for him and Pagan. I think that’s true of a lot of bands.”

Strawpeople - Mark Tierney and Paul Casserly with Whakatane vocalist Merenia.

The track also led to an influx of offers from ad companies for soundtrack work which would help fund the next album, Worldservice.

Still many local commentators remained puzzled by the band. “We’re not good guitar pop, which is what New Zealand specialises in,” Tierney told Rip It Up’s Donna Yuzwalk in 1990, who seemed bemused by the pair sitting before her.

“In the States and Europe they’ve got a much more flexible idea of what dance music is and how raucous you can be with electronics. In New Zealand, although bands like the Headless Chickens and NRA and Emulsifier are trying to break it down, people still have a pretty rigid idea of what they’re supposed to do with sequencers and samplers.”

When she asked whether they considered themselves dance music Tierney replied, “Stock, Aitken and Waterman make dance music. So do Tackhead. What end of the spectrum do you fit us in? We listen to Public Enemy as well as Chet Baker ...”

While Hemisphere didn’t sell particularly well, it appeared on numerous US college playlists and received good reviews.

“These arrangements are tasteful and executed with a kind of internal logic that, while recognizing a good idea retains enough discipline not to over use it,” said US magazine Options. “The Strawpeople are to be commended for being more genuinely musical than many who work in this genre and for utilizing the samples, both instrumental and spoken, with subtlety and intelligence”.

Looking back, Tierney has a soft spot for the album. “Because I can literally hear us changing from experimental wackiness to a pop band.”

Studio art

That pop element would come to the fore in the next two albums. Tierney was becoming a master in the studio and Casserly was also gaining confidence in song craft. What they lacked in musical ability was more than made up with an acute sense of taste and some of the best ears in the business.

Tierney described their aesthetic to Pavement magazine: “Something like Edith Piaf with a good orchestra; or listening to Italian opera on a rooftop in Morocco; or wet streets at five in the morning. These are the sort of things our music tries to reflect. I think Strawpeople are desperately romantic.”

While Casserly reflected to Stamp magazine, “We use anything from talkback radio, to ads, to rugby league commentary and traditional Māori waiata. The way we mix it makes us different and unique. We cross both bridges because it sounds international but it has a real New Zealandness to it.”

Once they were in the studio it was a very organic process. “Any playing we get others to do, because that will have a different feel,” Tierney told NZ Musician. “I guess the whole idea is to create something outside of ourselves ... to create music we like that we didn’t actually know we could make.”

He described to Pavement how a typical Strawpeople track came into being. “You might see a bit of something on the news or hear a bit of music and think, ‘that sounds good’. Then all the ideas get thrown in the pot and we hassle about them and cut them up ... we might say, ‘I read this great passage in this book’ or ‘I saw this film and it has such a beautiful mood. Why don’t we do a song that has that mood?’ ... then we’ll try and put chords and textures together that evoke that mood.”

If it sounds easy it was often a fraught process in reality. “We argue, a lot,” admitted Tierney.

Fiona McDonald told Pavement in 1995, “On a professional level Paul is the easiest to work with ... Mark can be difficult to work with. But then so can I. If you’re sure of something you will argue for it, and Mark can be dogmatic. It’s definitely advisable to be strong when you’re working with Strawpeople.”

Fiona McDonald, Strawpeople.

In 1992 McDonald (who would win Best Female Vocalist three times, in 1991, 1993 and 1995, for her work with both Strawpeople and Headless Chickens) left the band to join the Chickens full-time.

“However, we were still signed to Pagan,” recalls Tierney, “and Trevor was enthusiastic about our new stuff. We told him Fiona was leaving but we would carry on and finish an album. We had ad money coming in so we even used bigger studios and other engineers. We finished it in early ’92 and put it out. Neither of us was really happy with it.”

Worldservice (1992)

Worldservice would be the last Strawpeople record to be released on Pagan. Its lead track was a moving gospel-tinged version of John Hiatt’s ‘Have A Little Faith’, sung by a teenage Stephanie Tauevihi. The track was inescapable at the time and demonstrated how wide-ranging their musical ambit was and the fluency the pair had achieved in the studio.

Another highlight was ‘Trick With A Knife’. “I brought in the underlying rhythm and loops,” remembers Tierney.

“Paul had the killer chorus phrase [from a book by Michael Ondaatje] and played the strings, Fiona came up with the vocal melody and we all fought over the rest of the lyrics. We added the great Joost Langeveld on bass, some epic guitar chords from Trevor Reekie and the mighty Rhythm Slave (Mark Williams) for a burst of rap for a middle eight and bam, we had it. I’m pretty sure we only used 8-10 tracks to record it. If that song had been released internationally at the time we wrote it [1991] then our whole lives would have been different from that point.”

Strawpeople featuring Fiona McDonald - Trick With A Knife (1994)

The album also featured stellar interpretations of local songwriter Ted Brown’s ‘Love Explodes’ and the original ‘Dreamchild’ which the Headless Chickens – via Fiona McDonald, who co-wrote the song with Casserly and Tierney – would soon appropriate as their own, renaming it ‘Juice’. The reworked track would be a highlight of Broadcast.

The track was a big hit for The Headless Chickens and is still a bone of contention with Casserly. “It still shits me that The Headless Chickens renamed it when they covered it, calling it ‘Juice’ – I might sue the fuckers.” Although with Casserly – one of our finest satirists (his twitter handle is @drunkmuldoon) – that should be read with a wry grin.

While follow-up Broadcast would eclipse the success of Worldservice, the earlier album contains the essence of the Strawpeople sound and ethic – as well as many of the tracks that would make up its more lauded follow-up. But for many, the versions of ‘Have A Little Faith’ and ‘Trick With A Knife’ here remain the definitive ones.

In a 2011 Kiwi FM list of the greatest New Zealand albums, Worldservice was the only Strawpeople album to feature, clocking in at No.45.

When the Chickens offered Strawpeople an opening slot at one of their sold out Gluepot shows it would be the only Strawpeople live appearance with Tierney. (In early ’97 Strawpeople, with McDonald fronting, played Melbourne and Sydney). Casserly hated it. “My memory is that Mark and I got talked into a show, were woefully underprepared and then had a shocker,” he recalls.

“We had a great drummer but he couldn’t hear the sync click, it all fell apart like a bad pavlova. Our friends seemed to get a kick out of the shambles, the Germans have a word for it.

“I think that early shitty gig taught me a lesson, if you are going to do something do it right, but live was never my thing. I thought making good music enough of a challenge, still haven’t got there, will keep trying. As for success, could have tried harder I guess. Sue me.”

--