Berlin, 1 December 1989: Straitjacket Fits are nearing the end of their first world tour. They started on the West Coast of the USA, took on the East Coast (including the prestigious College Music Journal Conference with The Verlaines in New York, where both bands reportedly tore the roof off) and then moved on to Europe.

Straitjacket Fits in a 1988 publicity photo: John Collie, Andrew Brough, Shayne Carter and David Wood - Photo by Jonathan Ganley

The Straitjackets have a few major fans in the UK music press and spent most of their first two days in London doing interviews. They also recorded a Peel session and the title track of their Hail album was chosen for a flexi-disc to go out with the independent record industry trade mag The Catalogue. A special version of the LP, with the first four tracks replaced by those from the Life In One Chord EP, has been released by Rough Trade Records.

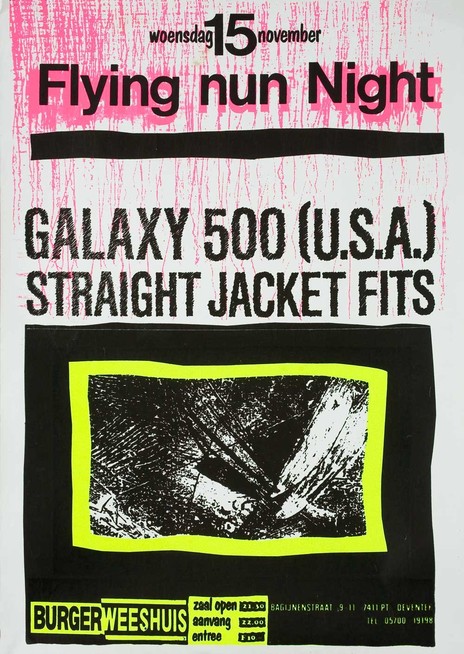

The Straitjackets began the European leg of their tour, a double-bill with hip Bostonians Galaxie 500 (handled by Chills manager Craig Taylor), with a messy, manic packed-to-the-rafters night at the London Powerhaus. In the spirit of the times, Rip It Up decided to catch up with them in the grooviest city on the continent, Berlin (well, Prague is probably groovier, but they ain’t playing there).

Any visit to West Berlin at the moment is, it seems, a voyage to the Pointy End of the 1980s. You can’t even get a cheap flight there for love nor money – you take whatever you can get in the way of expensive flights. Even Pan Am’s crummy “Clipper” jet service is subscribed to the hilt.

It certainly has a feel well beyond what should be an inconsequential European shuttle trip from Heathrow. Post-Lockerbie and pre-Christmas, Pan Am’s security verges on the paranoid. You have to have your baggage X-rayed to even be allowed to check in. Men from private security firms work their way up the queues for the X-ray machine, asking questions and looking deep into passengers’ eyes for a hint of the black heart of the international terrorist.

“This is your bag, sir? And when was it packed? Did anyone else pack it for you? Has it been in your control ever since being packed? Have you been asked to carry anything for anyone else? Is there anything in here which might be mistaken for a weapon?”

Mild-mannered family men turn shifty-eyed under the security officer’s gaze – everyone has something to hide.

No one knows quite where Straitjacket Fits are – and no one knows where they’ll end up staying.

Further through the security maze, travellers with Arab passports and suspicious moustaches have their hand luggage emptied and inspected and everyone is given the who-when-where-what treatment again. The entire contents of my sponge bag are of course made of Semtex and the detonator is cunningly concealed in a cassette copy of In Love With These Times ...

Night falls early in Berlin at this time of year – it’s pitch black not long after 4pm and seriously cold in this phone box. No one knows quite where Straitjacket Fits are – somewhere along The Corridor, the narrow isthmus of highway that connects the city with the rest of West Germany, perhaps – and no one knows where they’ll end up staying.

Many of the hotels in town are full and have been for weeks, ever since November 9, that extraordinary day when the East German government faced facts and opened the wall at the edge of the world.

Like every city in the Judeo-Christian world, Berlin is gathering pace for Christmas, and the city’s shops and stores, impressive at any time, shine all the brighter into the cold, clear night. They are full of the fruits of the strongest currency in Europe, and the second strongest in the world, and it’s not hard to imagine how overpowering they must have looked to the first hordes of visiting Easties. In a way it’s an unfair first taste of Western capitalism – it doesn’t work this well everywhere else.

The hostel is dominated by hi-volume American college students, you can hear them all the way down the hall. A quiet young Frenchman unpacks his bag. He’s here for the same reason as everyone else.

“I just had to be here,” he explains. “Just to see the wall coming down...”

Jason is a hi-volume American college kid in a bar: “Hi, I saw you on the flight – would you like to come and sit with us? My name’s Jason – like in Halloween I, II, III, and IV.”

His friends have names like Brad and Sammy and they’re on a pub crawl. They all go to a small, private college in the Sussex countryside and play incomprehensible drinking games.

They’re okay really. They even smoke roll-yer-owns. Jason apologises for being loud: “Do you find us too loud? Americans are so loud, aren’t we?”

It’s okay, I say. You wouldn’t be Americans if you weren’t. Two bars further on we enter a place populated only by the owner. It soon becomes clear why he’s the only one there. Not only is he arseholed drunk, but he’s a sexist shit. We stay for a round of beers and a shot of Jägermeister, a thick German spirit that tastes like cough mixture and warms the cockles. Outside, Brad unzips his ski jacket and produces a full bottle of bourbon, souvenired from the bar. “Ich bin ein Berliner!” he proclaims. “Ich bin ein Berliner an’ I got the JB!”

On the way back to the hostel, a plaque in a small park grimly commemorates National Socialism: “1937-1945.” In the far corner another monument remembers Stalin.

By the time another crisp, clear day has dawned, there is already a long, slow queue of East Germans waiting for their gift of 100 deutschmarks from the West German government. By Christmas, something like half a million deutschmarks will have been dispensed and recycled into the West German economy. Many West Germans are cynical about the handout – they see it as a propaganda stunt and consider the money would have been better spent as development aid but the fact is it allows these people to spend a day as players in a game they’ve never been allowed to play before.

It’s easy to spot the East Germans in a crowd – the shitty plastic shoes, the jumble-sale clothes. But more disturbingly, the years of separation have redrawn them physically – their faces and frames speak of bad diet and there’s a weird greyness that can only be put down to the living of life without horizons. These people might blend into a deprived area of London, but amongst the shimmering, robust West Berliners they look small and timid.

Along the footpaths of the town centre, crowds gather round stalls selling cheap novelties – junk jewellery, bad cosmetics and gimmicky cigarette lighters. It’s a little bit sad, maybe, but kind of fun. And it won’t last.

For a city surrounded, West Berlin contains a surprising acreage of green space. The sprawling Tiergarten runs right up to The Wall, along past the Brandenburg Gate, the sight of such extraordinary scenes on the night of November 9.

I find a jagged piece of metal and a hammer and chip until my arms ache.

The international TV crews are still there round the clock, waiting for the wall to fall, but it seems more likely to disappear through tourist attrition than act of government. In an extraordinary scene repeated daily, dozens of chisels are hacking at the concrete in pursuit of 1989’s ultimate Christmas present. It’s a lot harder than it looks on the telly (and, in fact, this is the hardest part of The Wall), but people keep on hacking because it feels good. Holes between the huge concrete slabs have already been opened up and stare into no-man’s land.

I find a jagged piece of metal and a hammer and chip until my arms ache and it’s one of the most enjoyable things I’ve ever done. There’s a real sense of attacking an edifice of the authority that messes up ordinary people’s lives in any country in the world.

The youthful East German border guards can only stand on top of The Wall and watch. They no longer carry machine guns, but handguns discreetly concealed in leather holsters, and they pose for photos and chat shyly to girls. Further down, a man quietly passes a couple of hundred deutschmarks to a guard through a hole in the wall.

There’s a lot of fresh graffiti along the wall, and chunks of concrete with paint on are the most treasured souvenirs – partly because they’re so hard to work off. One graffito, shining and new, bears the message “NO EUROPE WITHOUT BERLIN” in German, French and English. It’s a message for the times – Europe will fall apart if it doesn’t integrate first. Gorbachev’s “common European home” is the only way to cope with the emerging ethnic nationalism of the Eastern republics. Ethnic nationalism is going to be big in the 90s.

A young Berliner is selling T-shirts which merge the two most popular media figures of the moment: Gorby and Batman. GORBATSHOWMAN!

And thence comes rock’n’roll. Yes, says the promoter, Thomas, Straitjacket Fits are in town, but they’ve gone to get a piece or three of The Wall. They’ll be back at 5.30pm.

There’s time to return to the centre of the city, around the glittering Kurfürstendamm, where East Germans are staggering back to the border laden down with the important things in life – video recorders, colour TVs and ghetto blasters. These people are spending their life savings. Either that or they’ve been picking up hard currency by selling cheap goods from the East at flea markets – people come from as far as Poland to do this.

But there is more to it than consumerism – something the East German government failed to understand. A Sony Walkman is no substitute for a say in running your country. Would that we had such a clear view of our own occasionally shabby democracies.

Straitjacket Fits with Galaxie 500 in Europe, 1989

You may have seen the Ecstasy club before. It was the site of the live scenes in Wim Wenders’ Wings of Desire, although you wouldn’t know it. It’s situated in a part of the city where the Turkish community is strongly represented.

Ecstasy is a boon to touring bands, because it has its own, fairly tidy, accommodation upstairs, not to mention pool tables, table football and an excellent kitchen. Straitjacket Fits are relaxing upstairs, tucking into the spread in the kitchen and comparing pieces of The Wall. They’ve just had a rare day off in nearly three weeks of touring. During this time, everyone but Shayne Carter (the only non-drinker in the party) has had a bout of severe flu – not very pleasant when you’re spending hours every day in a draughty van in sub-zero conditions. They’ve done Holland, Paris, Switzerland and much of West Germany. If it’s Friday this must be Berlin.

Curiously, everyone agrees they’ve been playing more consistently well than ever before. The last seven gigs have been top-hole and there have only been a couple of real duds in the whole tour.

David has the flu but he’s more concerned about his bass strings, which haven’t been changed since Amsterdam. Manager Debbi Gibbs reluctantly agrees to venture out into the cold for a new set.

“In case you can’t get any, I’ll boil the ones I’ve got,” he says.

You’ll what?

“If you boil old bass strings it takes all the grease off and they sound like new,” he explains. “For about six songs. And then they’ll probably snap.”

Shayne wanders in, back from a radio interview and we arrange to have a chat for publication in Rip It Up. “What’ll we talk about?”

The 90s, man.

Straitjacket Fits in 1990: (clockwise from left) Andrew Brough, Shayne Carter, John Collie, David Wood. - Photo by Tony Mott

From what you’ve said you seem to be going from strength to strength on tour.

“Yes. Definitely. Just playing consistently to a lot of strange audiences on tour, transporting it to different parts of the world … the first few gigs we did were a matter of being freaked out by playing to a bunch of foreigners. The first gig at Long Beach we soundchecked with two real live Americans in the room – and it was a mindfuck. Oh my Gard! Real live Americans! And here we are, these New Zealand dorks playing rock’n’roll to them! But we got past that and we just found that an audience is an audience – and that’s a really important realisation.”

Do you wish you’d done it sooner?

“No, not really. I don’t think the band’s really been ready ’til this stage anyway. I look at our recorded stuff and that’s our first live set and now we’re writing stuff that has moved on from that, which is going to be the essence of the new album. But even now I can see the next avenue coming up as well, so it’s going to be real interesting writing the next batch of songs. You always wonder in New Zealand exactly where your music fits in, does it apply?”

And you’re clearer about that now?

“Yeah – and for a while I wasn’t. I thought, well who wants to hear another guitar band from New Zealand? But I think our music definitely stands in the now and there’s a place for it. As someone once said to me, a good song is a good song, whether it’s written on a sampler, a guitar or a piece of wood.”

So how’s it going to be going back to New Zild?

“I think we’ll go back wiser. You wonder about what differences an experience like this will make to you, because from New Zealand the rest of the world is so far away it’s incomprehensible in a lot of ways. It’s not a reality – it’s what you read about and what you see, but you don’t experience it. But it is now a reality.

“And the thing is the best gigs we’ve had have felt pretty special. So we needn’t be overawed by any kind of inferiority complex on our part. New Zealanders are really down on themselves, incredibly self-critical.”

“A gig has to be a scorching, blinding experience for us to think it was good.” – Shayne Carter

Why is that?

“I don’t know, I think it’s a mood that’s developed in the country over the last few years. There’s always been a tall poppy syndrome but I think there’s been a loss of confidence after the halcyon early days of the Labour Government – I think a lot of people are hurting. It’s a New Zealand syndrome anyway – you don’t like success and you almost feel guilty about it.

“This band definitely has the self-critical aspect anyway, we’re really down on ourselves and a gig has to be a scorching, blinding experience for us to think it was good.”

Have there been times of “fuck, what am I doing with my life?”

“Uhhh ... lots. Every bad gig! That’s the thing about playing music, especially when there’s no tangible rewards. Just that whole insecurity of doing this – you experience it on every tour. One night you feel you’re the best band in the world and the next you think you’re shit. I think to remain mentally healthy, you’ve got to develop an attitude that’s gonna get you around that. Playing consistently like this helps you do that.”

So what have been the highlights so far?

“There’s been a lot of little incidents … the maniac who dropped the piece of paving stone on us in LA – that was one very weird one. The CMJ conference was definitely one of the highlights. It was such an important gig for us – we were unknown, we had no records out in the States – and we pulled one right out of the bag, possibly the best gig we’ve ever played in all ways. That was the gig that really convinced me we have got something. This week has been good, going to the Berlin Wall – I saw a family coming out and they had the biggest grins on their faces and they waved and they were fucking happy.”

It’s a good time to be here.

“Yeah. Being here while this is happening – and going to San Francisco two days after the quake, it feels like you’re following history around in a way. Every bit is turning it on for you in one way or another.”

You’re certainly at the pointy end of the 80s here, the edge of the Western world.

“Yeah, the whole vision of peace or something looks like it could be becoming a reality and people are gonna live side by side. And you can call it hippie utopia or any cynical thing you like, but it’s truth and it’s monumental.”

Everyone seems pretty optimistic about the 90s at the moment.

“Definitely. The weird thing about being in Germany is that what’s happening here is going to change the focus of the world, in that you’ve always had this scary game of chess between the Soviets and the States and all of a sudden you’ve got what could be envisaged as the threat of a reunified Germany, such a powerful country – it’s going to change the balance of the world but hopefully for the better. Berlin represents the whole divide and if The Wall’s coming down it’s pretty symbolic.

“It was even interesting going to the States because we get such a warped view of it through crap media and the politicking that goes on, but meeting the people you see that there’s a really sad poverty and people getting shat on and the whole rat race in a place like New York, which really is all the dog-eat-dog clichés.

“It’s weird coming to Germany, too, seeing this incredibly powerful country which still has to suffer the humiliation of occupation. And we visited Dachau the other day – I initially thought it was a kind of ghoulish thing to do, but it was really important to see that it happened and it existed and it was horrible – but true. Very sobering.”

So what would you hope would happen before the year 2000?

“That we get a really big record contract! This is my universe, kids! I don’t know, it’s all moving at a bewildering rate this year, after years of stagnation and stalemate … I just hope it keeps moving in a positive direction. You don’t want it twisted around as a ‘validation of the Free World’, but I hope it’s possible that people will have that cloud of oppression lighten from over their heads.

“And it’s happening all over – even the fact that the environment has become so high in peoples’ consciousness. It doesn’t matter whether you’re communist or what, you’ve got this threat of the atmosphere disappearing. So that must influence people’s thinking. I think the whole green consciousness thing has wider implications than the physical environment anyway.”

A lot of pundits are picking the New Age consciousness bag for the 90s – what do you think of that?

“I actually used to be very cynical about all that shit, but these days I think that whatever a person needs to get some sense of peace and contentment, well fine, so long as it doesn’t involve hurting anyone else. So whether it’s playing your rock’n’roll guitar or meditation, fine, it’s alright by me.”

“whatever a person needs to get some sense of peace and contentment, fine ... whether it’s playing your rock’n’roll guitar or meditation.” – SHAYNE CARTER

How about back in New Zealand, what hopes do you hold for things working out there?

“I don’t know because it’s always seemed so self-contained. There’s got to be an improvement in attitude. If a National government gets in, which seems more and more likely, then it’s going to be a real step backwards. For all the fuckups Labour made at least they showed it’s possible to get a new vision. It meant leaving behind traditional things associated with the party, but it meant a different vision of where the country could stand. If we go back to National and see it being very regressive and probably quite out of step with what’s happening in the world. But communication is getting such that the world is shrinking anyway, so you could see further changes in the country just because that’s the way it’s going internationally and influences are far more direct now.”

You ever think of writing a political song?

“Ooooh … whenever I think political song I think of the Clash and I could never write a fist-waving boys-own chorus, kill-the-scum type of thing. But I wanna see what my head does when I get back and what I want to write about from this experience. I think I could, but it would relate back to people rather than governments and bureaucratic things.”

Given the Māori blood in your veins, has the Māori consciousness thing affected you?

“Not really, just purely because of the fact that my dad was adopted into a white family, so my contact with Maoridom has been very, very limited. I can sympathise with arguments but I never really immersed myself in them because I’ve never really had that close contact. But with the contact I have had the things I get out of it are the warmth of the people, the lack of selfishness and being far more aware of your actions and the wider connotations they can have. Self-advancement isn’t important – your social standing isn’t important, so you don’t have to strive to get to the top of the heap and step on people on the way there. That’s the thing I respect about the culture. As far as political arguments go I can sympathise and there’s a lot of shit to be undone but you’ve got that situation with indigenous people all over the world.

“But I’m proud of my Māori blood, I’m glad I’ve got it in me, but the fact that my dad was adopted means I’m not even sure what tribe I belong to – and that’s a bummer because I’d like to know.”

The thing that I relate to most is the attitude to the land.

“The language and everything always relate back to the land, yeah.”

And I think even New Zealanders of European stock tend to realise when they get here that they’re not European, they’re of the South Pacific.

“I’ve been thinking about the history of mutual mistrust and suspicion that there’s always been here with all these countries so close together, alliances and conflicts … New Zealand should really be exempt from that, and in a way it is. Sure, race relations aren’t as good as they could be, but I think there’s quite a liberal edge to the New Zealand character. You’ve got your racists and your boors but I think there is that tinge to the people.”

Especially compared to, say Australia.

“Australia’s so much more chauvinistic in all ways, whether it’s the attitude to women or minorities – I don’t know what the cause of that is. Australia’s much more Americanised – New Zealand’s more English. But I don’t know if I like the English either!”

I think it’s less an English but more a Scottish and Irish influence that has shaped the New Zealand character.

“Right … I’m really pissed off we’re not getting to Scotland. But there I was saying we should all love each other and then running down the Australians and the English … oh well, hypocrisy is the human prerogative.”

--

And speaking of the Gaelic races, the early arrivals at the gig include Ken, an Irishman who came to Berlin three months ago for a visit and, as Irishmen tend to do all over the world, now finds himself living here. He was fortunate enough to be on hand for the extraordinary events of November 9.

“I went to the wall and it was wild, like a huge party. I even heard that someone, somehow, got a car up on top of the wall and drove it along. There were people handing you drinks and slapping you on the back, and glasses of glühwein going through the wall to East German guards. It was like that for a couple of weeks, just a big party. Only better than your average Berlin party where they sit around playing chess and making serious conversation.”

His friend Steffi interjects: “People at parties here spend all their time talking about where they’re going to get a room to live. What’s happened now is that Berlin has become so crowded. It’s almost impossible to park your car anywhere, there are queues in shops. The whole East German system is based on queuing but people here aren’t used to it – they’re used to getting everything fast.”

It’s not hard to see how that would become a problem when you step onto the thronging streets around Ku-dam. Even queuing times to get across to East Berlin have doubled or trebled. But what about this perceived threat of a reunified German nationalism, of neo-Nazis even?

“There’s still a hard core of neo-Nazi youth here – not many, but they’re evil bastards,” says Ken. “At one of the big democracy rallies on this side, a bunch of them ran out with scarves over their faces and sprayed mace into the crowd. They just missed me but half a dozen people got a faceful. For a while they had a basement club where they met, but one night about two or three hundred people came down and completely smashed the place up so it was unusable. It’s a shame it has to be like that but they have to be shown that what they were doing wasn’t gonna be tolerated.”

Galaxie 500 are on stage. The bands are taking turns to play first and it’s Galaxie’s turn tonight. The tour was originally conceived as a double-bill, but Galaxie’s head start in the press and album stakes and the fact that they’ve done Europe before has meant that, outside of the UK anyway, they’ve had very much main-act billing. Which, for the Straitjackets is just the breaks and the two bands get on well.

The trio’s singer-guitarist Dean Wareham was actually born in New Zealand and lived there ’til age seven, then in Australia ’til 14 before moving to New York with his family and Boston for college, where he met bassist Naomi Yang and drummer Damon. And maybe there’s some roots happening in the music, because they call to mind a number of New Zealand combos, most of all a mellowed-out Pin Group. The tour seems to be making him consider his birthplace and he makes cryptic references to “the New Zealand sense of humour” (“I mean, what does ‘cold enough to freeze the balls off a brass monkey’ mean anyway?”)

They come off stage and barely have time to open a drink before retiring into a bedroom for a typically serious interview with a typically serious German journo.

New songs are sharply in focus now, and they’ve lost the pub-rock feel.

By the time the Straitjackets go on at about 12.30pm, the crowd has thinned out a bit and, it seems, is rather more suited to Galaxie’s more meditative approach than Straitjacket Fits’ rock’n’roll. They go in big for polite clapping and they’re so laid back that some people only start clapping as others finish, so each round of applause pitter-patters on for ages. The Straitjackets are playing too well at the moment to play badly, so they play as well as could be expected in front of an audience that’s not giving a lot back. New songs are sharply in focus now, and they’ve lost the pub-rock feel that sometimes crept into them in New Zealand. Pub rock comes from playing in pubs – it makes a big difference having a promoter who feeds, waters and houses you when you’re used to fat-bellied pub managers who don’t give a shit so long as you don’t get in the way of beer sales.

After the gig and some talking shit, half a dozen of the party, including Dean, go down to the club’s disco basement to play manic table football. The disco is weird – they play 60s tunes like ‘A Hard Day’s Night’ (twice!) surrounded by gross-out heavy metal. “I live on the edge/ I live for danger!” screams one particularly horrible bit of Euro pomp-metal. Yeah, sure ...

As Gorby and Bush are failing to get it together on the Mediterranean and most of the East German communist party leadership is resigning in anticipation of serious corruption charges, Straitjacket Fits are loading up the van they’ve rented from the Chills and preparing to drive six or seven hours to Engar.

“Engar’s nice – they do a really good spread,” offers soundman Gordon Rutherford. “They really make an effort.”

These are the things that life is made of.

All that Saturday, the centre of town has been seething, the broad footpaths packed. The inconvenience is more than balanced out by a sense that this is a Christmas like no other. There’s a lot to be sorted out (and not just in Eastern Europe), but for now there’s a lot to celebrate.

The area around the beautifully rebuilt Kaiser Wilhelm Church (that rare and wonderful thing, a real triumph of modernist architecture) is full of brightly lit stalls, selling food (sausages) and body-warming beverages. As night falls it is thronged by merrymakers, some of them even dressed as St. Nicholas (the real-life model for Santa Claus, a charitable saint born in, believe it or not, Turkey).

On a small stage, a man who may be the mayor of West Berlin is speaking. I can’t catch the words, but the tone is all warmth and hope. “Alles ist gut und alles ist lieber,” he finishes. “Alles ist gut und alles ist lieber.”

Everything is good and everything is better. It’s Christmas in the 1980s at the edge of the world.

--

From Rip It Up, December 1989, and republished with permission