“A million a year on records … that’s what’s spent in New Zealand. It’s very big business and half a million is spent in the Auckland province alone.”

It’s a warm summer’s evening in 1957 and the speaker is George A Wooller, esteemed radio man and soon to be head-honcho of UK company Pye’s New Zealand record division.

Wooller had invited record retailers to the swanky environs of Auckland’s Trans Tasman Hotel to announce Pye’s acquisition of local rights to US label Mercury. Up in the Sky Room, with views across twinkling street lights and busy downtown wharves, Mr Wooller’s guests sipped cocktails. Later a troupe of professional rock and roll dancers gave them jiving lessons.

As the midnight hour approached it's possible a cigar or two was lit and celebratory glasses clinked. Mercury was a classy label but the rump of its catalogue was jazz and, though it had The Platters, Pattie Page and The Crew-Cuts on its books, when it came to rock and roll – the new international sensation – its game was a little weak.

And while it’s understandable that Wooller and his colleagues were proud of their score, Pye (NZ) was at this point – at least when it came to records – still a minor player.

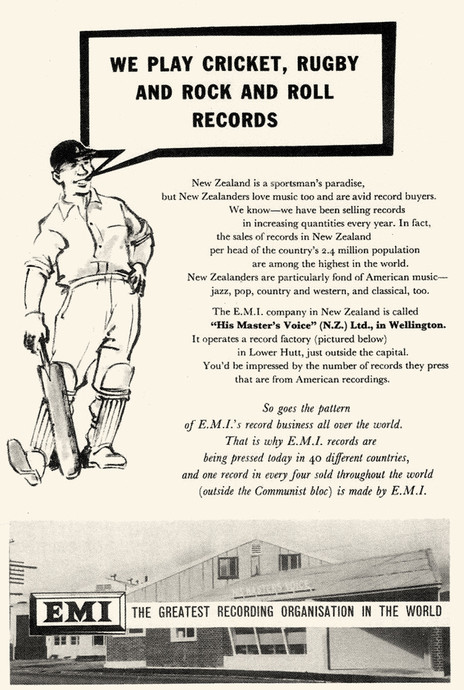

By far the biggest share of the lauded “million a year” was being enthusiastically pocketed by His Master’s Voice (NZ) down in Wellington. Spurred on by an audacious 1955 buy-out of the US label Capitol, EMI – the British parent company to HMV (NZ) – was focused on nothing less than a global domination of the record business.

HMV (NZ) "We Play Cricket, Rugby and Roll and Roll Records"

The company’s purchase of Capitol coincided with both the birth of rock and roll and Billboard’s official announcement that – in the United States at least – 45rpm discs were for the first time outselling the 78rpm format. New music was about to flow into New Zealand faster than ever and for a post-war generation coming of age, the timing was perfect.

This febrile period of Aotearoa’s history is detailed in Redmer Yska’s 1993 book All Shook Up. It’s the compelling tale of a country navigating a backwash of McCarthyite paranoia, illicit booze dens, sexual and racial inequalities and young Kiwis flirting with rebellion. Amidst all of the drama the stolidly establishment HMV (NZ) emerges as an important player, a conduit for discs that would soundtrack some of the era’s most notorious events.

The company’s stall was set out in a publication listing the complete inventory of 78rpm records it had released in New Zealand between January 1955 – March 1956.

HMV (NZ) Record Catalogue

Running to 52 pages of closely set Futura, His Master’s Voice (NZ) Record Catalogue is a marvellous document for enthusiasts of mid-20th century popular music. The list includes pressings from New Zealand, Australia and the UK and, armed with the timeline and context of events recounted in Yska’s book, is especially evocative.

On page 4, for example, is ‘Black Denim Trousers’ by US trio The Cheers. Released in 1955 on the HMV (NZ) Capitol imprint, it was banned for broadcast by the NZBS because of its references to delinquent motorcycle gangs. This, of course, only boosted its bona fides and it quickly became a jukebox anthem for the “milk-bar cowboys” who, with sparks flying from hobnail boots, roared up and down Auckland’s Queen St on their Triumph and BSA motorbikes.

And listed on page 36 (along with local romantic pianist John Parkin and The Ardmore Māori Choir) are The Penguins with their song ‘Earth Angel’. It’s this track that was playing on the jukebox in an Upper Queen St café called Ye Olde Barn while Johnny McBride was stabbed to death by Albert “Paddy” Black.

Coming less than a month after ne'er-do-well Freddie Foster was hanged for the March 1955 shooting and killing of his teenage girlfriend in another Auckland milk bar, outrage at this grim violence was – unsurprisingly – intense. Rock and roll would be judged by some to be an intrinsic facet of what Yska describes as “The drift towards moral chaos ….” A nascent generation gap grew wider.

But record companies exist to sell records. With newly affluent teenagers on one side and moral gatekeepers on the other what line would commerce decide to walk?

The brightest star in the rock and roll firmament was Elvis Presley. In May 1956, the New Zealand film censor, Gordon Mirams, hacked out a chunk of action from a goofy Australia Cinesound Newsreel due to play in Kiwi picture houses. The offending scene in ‘Rock and Roll Hits Sydney’ showed nothing of Presley’s own lascivious stage presentation but instead merely compared – in voiceover, while an Australian couple danced an exaggerated leg-wobbling jive – the male dancer to “Elvis, the Double-jointed Pelvis.”

As well as the new music being an incitement to anti-social behaviour, the country’s moral guardians were also fretful that just the mention of rock and roll’s most limber star might inflame teenage libidos beyond even their normal, hormonally charged state.

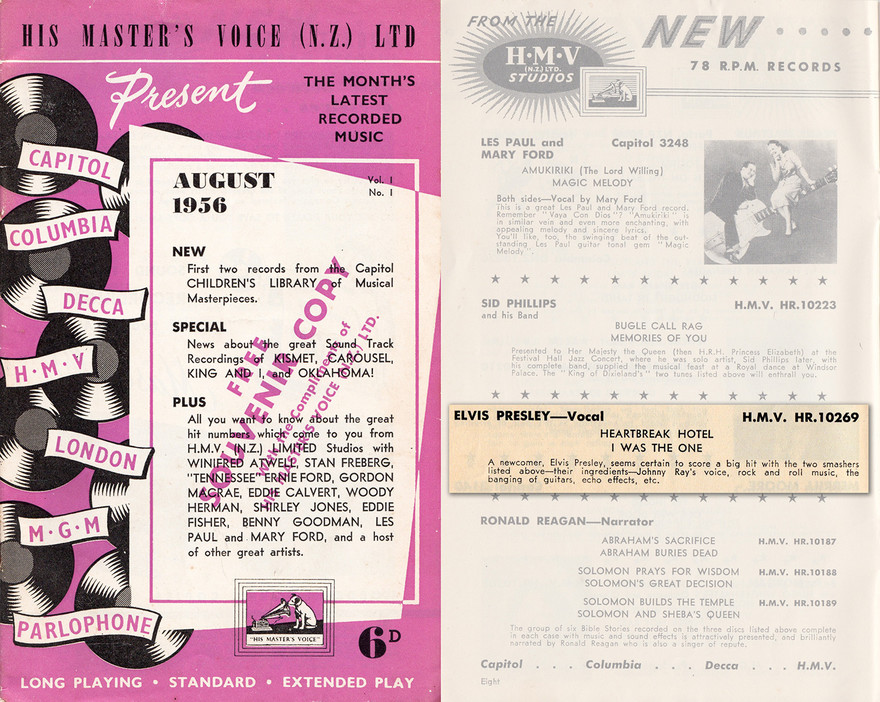

Despite the opprobrium, HMV (NZ) couldn’t ignore Presley’s rocketing overseas success. All Shook Up features an NZ Truth column from 17 July 1956 promoting the local release of ‘Heartbreak Hotel’. The press cutting – penned with barely concealed scorn – is credited as “The first known New Zealand reference To Elvis … .” (Actually, hip radio host Arthur “Cotton-Eye Joe” Pearce had broadcast Presley’s ‘Mystery Train’ on Wellington’s 2YD six months earlier.)

NZ Truth Elvis review, 17 July 1956 - from All Shook Up (Penguin, 1993).

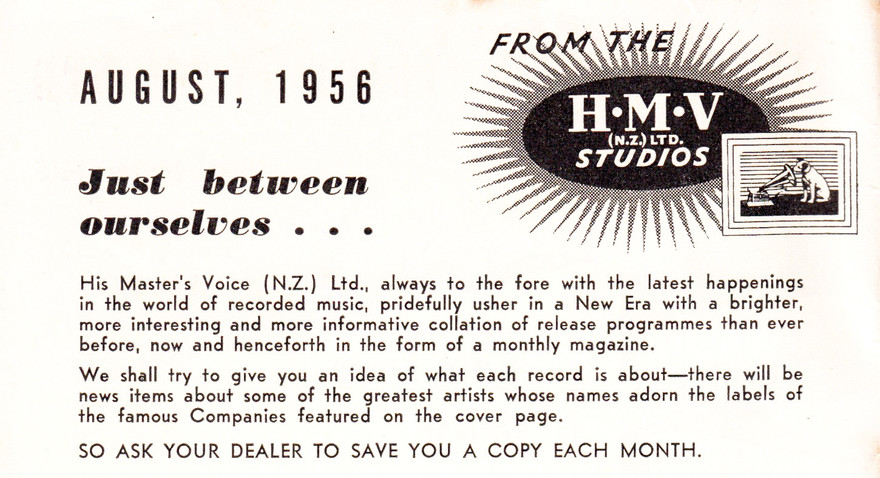

NZ Truth columnist “Middlebrow” was almost certainly been alerted to the new Elvis record by an HMV (NZ) press release. The company – ramping up their manufacturing operations to cope with the post-Capitol influx of material – needed to support their growing inventory with a more agile approach to promotions. The solution was to supplement the traditional catalogue system with an always up-to-date monthly magazine. This would enable retailers – as well as their customers – to be regularly alerted to the company’s newest releases.

HMV (NZ) Present, August 1956.

HMV (NZ) Present, August 1956. As well as 'Heartbreak Hotel', notice the 78s of Ronald Reagan reading Bible stories.

‘Heartbreak Hotel’ was the first fruit of RCA Records 1955 signing of Presley and had been released in the US in January 1956 to an initially lukewarm reception. When issued in the UK on HMV in March, the British music press were similarly nonplussed. But by the time New Zealand decided to pick it up for a local single release, the song’s outré soundscape and narrative psychodrama had sailed over the naysayer’s heads and entranced a worldwide generation of young listeners.

What’s odd is that despite the impression one gets from “Middlebrow” and the zesty (but slightly baffled) review in HMV (NZ)’s new magazine, this was not actually Presley’s first New Zealand appearance on record. The songs ‘Heartbreak Hotel’ and its B-side, ‘I Was The One’, were previously featured on a locally pressed compilation called E-Z Country Programming – No. 3.

E-Z Country Programming, No. 3

Presented in a unique cover – designed in-house at HMV (NZ) and printed by Coulls Somerville Wilkie Ltd – this exceedingly rare 10” record is, possibly, the world’s first commercially retailed LP to feature tracks by Elvis Presley: a distinction it happens to share with another New Zealand Record.

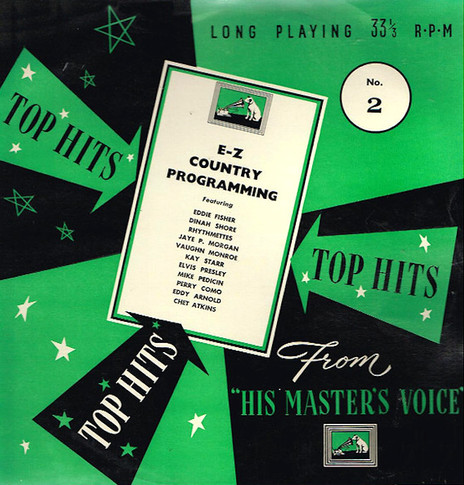

E-Z Country Programming, No. 2

Some breathless internet speculation dates the release of this sister 12” LP to 1955. The two Presley tracks – ‘I Forgot To Remember To Forget’ and ‘Mystery Train’ – had originally been released in the US by independent label Sun Records in September 1955. But it wasn’t until December when the tracks were reissued as an RCA single (with the sides reversed) that it would have become available for license by EMI and its HMV labels. It took until the end of February 1956 before the record hit the top of the American C&W charts which is the point that HMV (NZ)’s ears would have most likely pricked up.

Given the time it would take to receive the mother stampers from RCA, press the LPs, design and print the locally produced artwork and distribute the records through to New Zealand retailers, I’m inclined to believe that both the E-Z records were actually released simultaneously, some time between March and May 1956.

There are clues to their hasty conception: the shared artwork, typos, confusing numbering (there is no “No.1” in the series) and matrix codes and disc formats conforming exactly to metal master stampers manufactured in the US by RCA.

(The compilations had been originally produced for US disc jockeys as blank-sleeved pre-release radio promos. It’s probable that in early 1956, HMV (NZ) were offered the discs by RCA as brand-new off-the-shelf hit collections and accepted them as such; something made explicit in their subsequent packaging design. Elvis Presley – at this stage – would have had far less commercial pull for local Kiwi customers than, say, Eddie Fisher or Perry Como, who both appear on the collections).

All the evidence points to expediency, a need for HMV (NZ) to break their reliance on increasingly expensive (government restricted) import 10” and 12” LPs by manufacturing them on home soil. Rather than requesting tapes for this inaugural series of locally produced pressings, the company chose the most economic option, which was to use quality-assured metal masters from RCA who – despite their displeasure at EMI’s purchase of Capitol – still held the American rights to the “His Master’s Voice” trademark (“The World’s Most Trusted Brand”) and a distribution clause allowing HMV (NZ) access to its masters until the end of 1956.

Perhaps the most unusual thing about these two records – apart from their rarity – are the liner notes shared between both releases. The uncredited New Zealand-based author blusters extravagantly across the page, indulging in a flurry of Empire-era hyperbole at times so grammatically tortuous one’s head feels as if it’s being squeezed in an antique Victorian vice. But persevere and what emerges is a manifesto of sorts, a grandiloquent pledge that New Zealand’s godforsaken cultural isolation would be banished by the nourishing largesse of HMV: “… that gigantic disseminator of vocal, orchestral and instrumental music that flourishes under the aegis of the listening dog.”

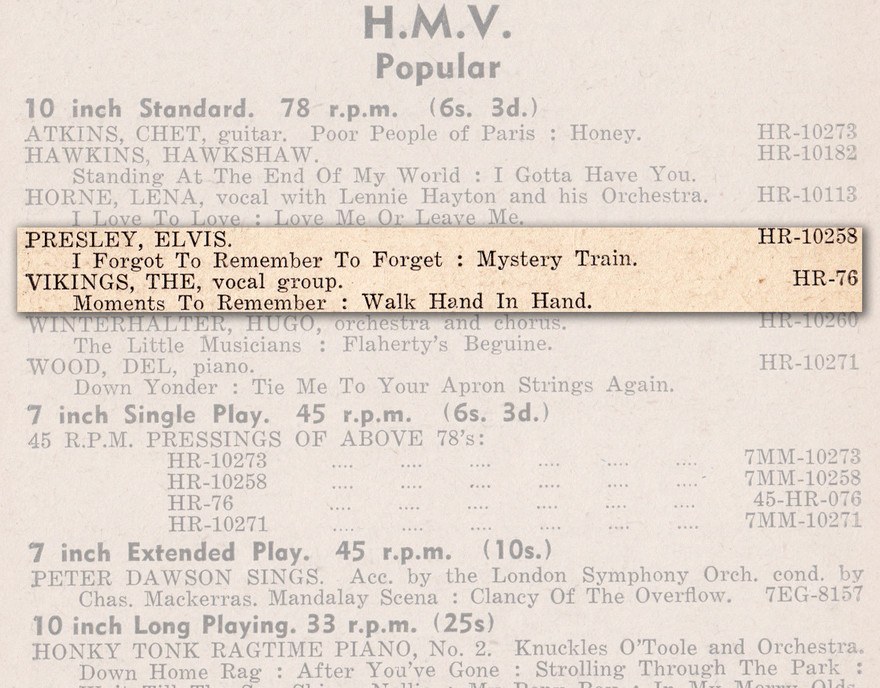

As well as issuing ‘Heartbreak Hotel’ b/w ‘I Was The One’ in July, HMV (NZ) grasped their last chance to exploit the young Memphian’s commercial potential and released the older recordings ‘I Forgot To Remember To Forget’ /‘Mystery Train’ in November 1956. (Puzzlingly, this final HMV (NZ) Presley record carries a catalogue number indicating it was scheduled for release before ‘Heartbreak Hotel’.)

As well as being pressed onto 78rpm shellac, these four Elvis tracks – liberated from the obscure E-Z compilations – were also available as 45rpm vinyl discs, the new lightweight and unbreakable 7” format soon to become the teenage Kiwi rock and roller’s sine qua non.

HMV (NZ) Elvis Presley - 'I Forgot To Remember To Forget'

'I Forgot To Remember To Forget' - The Record Monthly, November, 1956.

Sharing the spotlight, just below the King in his pomp, are Wellington vocal group The Vikings with their HMV (NZ) debut, ‘Moments To Remember’. An Ivy League-styled number it’s polite, skirting close to being anodyne. But it illustrates the gulf between rock and roll and the cozy popular music still soothing a generation of people around the world living with varying degrees of suppressed post-war anxiety and undiagnosed PTSD. The rebel-rousing energy of rock and roll – “Live Fast, Die Young” – jangled nerves and provoked anger amongst many adults because fast lives and early death had been a sobering reality during the years of conflict.

In New Zealand such “easy listening” material would prosper, remaining the bread and butter of a company like HMV (NZ) even as rock and roll and its various offshoots exploded into the popular culture. A data-rich analysis of New Zealand listening habits made by EMI in 1966 – possibly the peak of 1960s pop and rock innovation – reports that “generally a greater cross-section of the public appears to prefer ‘middle-brow’ music.”

But for thousands of New Zealand teenagers in 1956, this first wave of rock and roll and its promise of freedom from the “square” adult world, had lit a fire. Inspired by Elvis, young New Zealand talent sparked into action. Rejecting the tyranny of grey, baggy-arsed trousers, dowdy dresses and dull provincial lives, they strummed cheap guitars and flashed their dayglo socks. A receptive music business – right on their doorstep – was more than ready to record them.

Read: Sound and Vision 7, part 1: HMV graphics, late 1950s

--

Thanks to Jaesen Jones of Beatles Australia for additional EMI material