Lydia and William Williams with their banjos, Carlyle Street, Napier, c. 1890. Photo by William Williams. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington. 1/1-025685-G

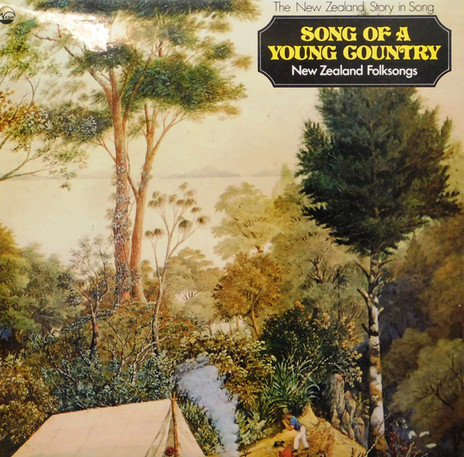

In 1971 singer, composer and folksong collector Neil Colquhoun released a concept album of songs by – or re-creating the experience of – the Pakeha pioneers of the 19th century. Among the writers were Colquhoun, Phil Garland, Rudy Sunde and many by unknown early settlers, collected in the 1960s. The multi-artist double LP on Kiwi Pacific Records received renewed attention in 2009 when it was included by Nick Bollinger in his 2009 book 100 Essential New Zealand Albums (Awa).

The 1971 album was followed a year later by an accompanying songbook, Song of a Young Country (Reed); this was re-released in 2010, in a lavish production by Steele Roberts.

Whether sung, played, read or listened to, the songs in this influential New Zealand folksong compilation and songbook provide insight and human colour to the bare facts of our collective past.

Song of a Young Country, a milestone in New Zealand musicology (Kiwi Pacific, 1971)

Music and vocalising have been in fluid evolution ever since the first humans slapped a leathery foot on a hollow rock, knocked a tree with a stick and it made a pleasing sound, or mimicked the cadences of birdsong and the rutting noises of animals to attract them on a hunt.

Millennia on from then, there are multiple music styles and labels. Folk music is one of many. This has been blending, hybridising or diverging since Woody Guthrie sang about the Depression and since the folk revival of the sixties when Joan Baez, Joni Mitchell and Bob Dylan sang out in protest; when civil rights marchers chorused aching spirituals about injustice, and since Odetta or Buffy Sainte-Marie told it like it was.

In New Zealand, folk clubs around the country host the works, from bluegrass, American urban blues, old-time country and Celtic stylists to Euro gypsy jazz, jug bands, a cappella harmony groups and soloists playing covers and originals.

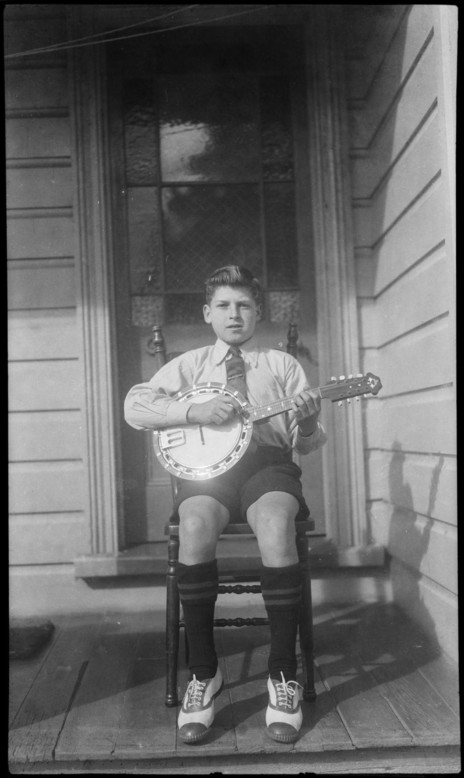

A young Rudy Sunde, playing his mandolin-banjo, Oratia. - Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections RSU-N-0034

The clubs also have a solid core of traditionalists who enjoy what they consider the “real” Kiwi folk music; that is, the songs, sea shanties, old ballads and work chants sung or recited by the people at the birth of these islands as a Treaty-formalised Crown-Māori nation. They were the sailors, sealers, wives and whalers, adventurers, bushmen and the like, who sang out their joy, humour, or misery during their hard-slog work and after hours; about bully bosses and fair blokes, madams and murderers, hardships underground and weird happenings above; about social milestones, triumphs, shipwrecks and other disasters.

Among those who love this trad folk is a rare group of song collectors. Holmesian by nature and dogged in pursuit of hidden musical wealth from the past, they are driven by native curiosity, scholarly imperative or merely the desire to refresh their own repertoires with new material. Whether by performing, recording, writing them down or musically notating them, these collectors have reinvigorated many a tale and melodic treasure that might otherwise have slipped away forever.

Phil Garland, from the original Song of a Young Country LP.

New Zealand’s foremost folklorist was Phil Garland QSM (1942-2017), songwriter and founder of the extant Banks Peninsula Folk Club, now called the Christchurch Folk Music Club. Phil travelled the country over many years, collecting, performing, writing about and lecturing on Kiwi folk heritage. He recorded around a dozen albums of songs or poems that he either wrote or put to music based on this material. Steele Roberts published his autobiography, Faces in the Firelight: New Zealand Folksong & Story, in 2009.

In Faces, Phil lists those who inspired him and supported his endeavours, from Rona Bailey and Herbert Roth (co-authors of Shanties by the Way, 1967); Frank Fyfe; Elsie Locke (Six Colonies in One Country); Les Cleveland (The Songs We Sang, 1959) and the NZ Folk Foundation (Scrub and Blackberry, 1981) to Roger Steele, of Steele Roberts Publishers, and Kiwi-Pacific Records.

Another among this group was Neil Colquhoun (1929-2014). His interest in collecting early New Zealand folksong and tales had been inspired by Rona Bailey and Jim Delahunty, with whom he performed at the 1957 Auckland Festival of the Arts. As a specialist music educator, folk performer, arranger and composer for stage, theatre and song Colquhoun was well placed to add to the canon.

Pictured inside Song of a Young Country are Neil and Barbie Colquhoun with their children Megan and Simon.

The 1972 book from his findings, Song of a Young Country – New Zealand Folk Songs, came after editing a small anthology in 1965 and forming a group called the Song Spinners to perform the material.

In the interim Colquhoun updated the book, adding new material he had collected and by what means, and expanding details on the provenance of each item. Roger Steele recognised the value of this collection and its deserved place in New Zealand oral history, and after further editing and polishing its presentation, Steele Roberts published it in 2010 as Song of a Young Country – An Anthology of New Zealand Folk Music; simultaneously the accompanying album was rereleased on CD by Kiwi Pacific Records.

The 2010 reissue of the Song of a Young Country anthology.

Roger Steele said, when questioned about the publication, “Song of a Young Country is one of the two great collections of New Zealand folksong, along with Bailey and Roth’s Shanties by the Way. It was out of print, so it cried out to be revived and updated, with additions, deletions and considerable editorial improvement.

“There’s been no major upsurge in interest, I regret, only minor, and yet this stuff is national treasure. One day Kiwis will latch on to the evocative songs that are an essential and exquisite part of our heritage. Neil Colquhoun himself was an under-recognised treasure, and this volume stands as a small but significant tribute to his song-collecting and tuneful arrangements.”

Neil Colquhoun, pictured in the 2010 reissue of the Song of a Young Country anthology.

In Colquhoun’s introduction to the revised edition, he describes it as being simply a songbook for singing through. He makes no apologies for modernising sources, if it has made for better singing or understanding, and for following the lead of renowned American folklorist Alan Lomax in filling in gaps with his own words and music.

Plenty of the songs of tradition have been modified and adapted through the centuries in the time-honoured folk process. “Since Chaucer did it,” Colquhoun writes, “there have been hundreds of authors who gained fame by recording or rewriting the oral tradition of the people.”

The book contains 74 songs, with chords, lead lines and words, grouped under categories about kauri gum, homesteading, sea shanties, whaling, rogues and rebels, union men, bush life and so on. Some are as he found them and for others, he created a tune then notated and arranged them, or filled in gaps with snatches of phrases he had gathered from various sources. The text is accompanied by assorted illustrations – archival photography and lithographs, with additional prints by renowned Kiwi modernist E Mervyn Taylor and a painting by Colquhoun, also a practising artist, as the cover image. There is also a short chapter with reminiscences by Colquhoun and Dorothy Ledingham about “folky” characters, each with a song or a “pocketful of ditties”.

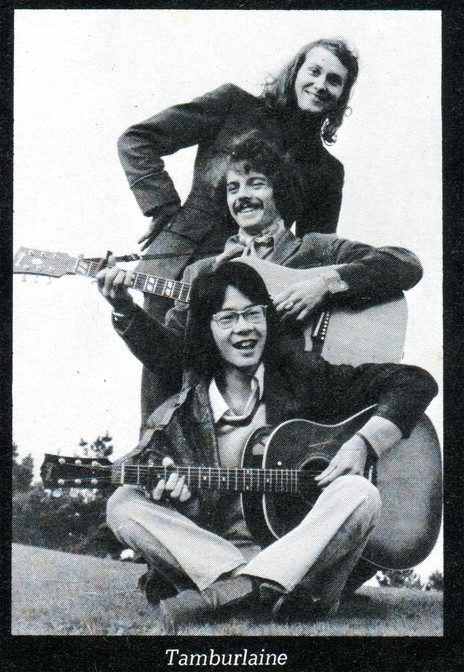

Tamburlaine's three tracks on the LP fused traditional song with rock and jazz, wrote Nick Bollinger.

“This book is for new singers, written simply and in easy keys,” Colquhoun writes, adding the intriguing instruction: “Any sharps or flats met with in the melody should not be treated too literally and would be best sung slightly off pitch.” One might assume by this that he means people should sing them out as naturally as possible without worry or pretence.

The songs here, anonymous and otherwise, have all been collected by song-finders in various forms from song and verse, to tall tales, snippets of story or whole songs. There are parodies to well-known melodies; words set to music and music to words, and a few verses by established poets such as Denis Glover (‘The Magpies’ – “Quardle, oodle, ardle, wardle, doodle”) and James K Baxter ‘(High Country Weather’).

Marilyn Bennett sang ‘My Man's Gone’ and ‘Railway Bill’ on the 1972 album.

Colquhoun’s historic notes include fascinating detail about the times. He writes that the anonymous ‘Shore Cry’, for example, collected in the US in the 1920s by American John Leebrick of New England, was attributed to former convict Australian Ben Turner, who set up a tavern around 1810 in wild Kororāreka in the Bay of Islands, the nation’s first capital and so-called “Hell Hole of the Pacific”.

The shanty ‘Blood Red Roses’ references stories about the privation sealers and whalers faced on remote New Zealand islands. Of five sealers, for example, who were picked up off the Solanders in Foveaux Strait in 1813, two had been there since 1808, dressing and sheltering in sealskins and living off seal meat. And another group of whalers were set down by a US ship with “a quart of rice, a half-bushel of potatoes” on the subantarctic Snares in 1810 and not picked up till 1817.

“Our captain he has set us down

And he has sailed for Sydney town

Come down you blood red roses, come down,

Just one split pea in a ten pound tub

Oh you pinks and posies,

Come down you blood red roses, come down.”

Others, like John Barr’s Scottish ballad ‘Altered Days’, indicate an immigrant culture through dialect. Colquhoun admits to modernising this and other songs, but the patois here is still thick:

“When to New Zealand first I cam’

Poor and duddy, poor and duddy,

When to New Zealand first I cam’

It was a happy day, Sirs.

For I was fed on parritch thin,

My taes they stickit thro’ my shoon,

I ruggit at the pouken pin

But couldna’ mak’ it pay, Sirs.”

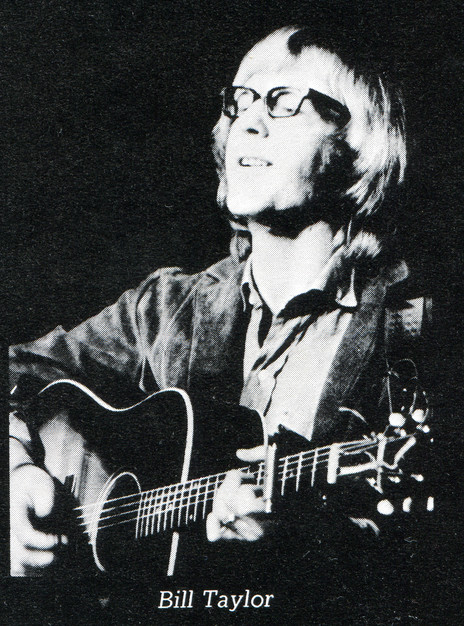

Bill Taylor recorded ‘Dug-out in the True’, ‘The Mill', and ‘Hundred and Fifty-One Days’.

Some New Zealand Company immigrants brought songs over with them and other songs reflect community life onshore. ‘Lullaby’, which has come down through seven generations of one family, is said to have been written by a Māori and a Pākehā woman who shared a close friendship:

“Look there’s a moon, it shines tonight,

Kowhiti, kowhiti, whitireia.

Now your mama will hold you tight,

Awhi, awhi, goodnight.

She’ll sing you, oriori,

She’ll bring you, kawe mau, to sweet sleep, hia moe,

So don’t peep! nenewha,

But just keep, noho, noho, closing your eyes.”

The catalogue addendum has a brief description of each song’s provenance and Colquhoun’s contribution. For example: “‘End of the Earth’ – collected and reconstructed from a letter-fragment found at Paparore, 1965; words anon, music reconstructed by Neil Colquhoun” and “‘New Chums at the Diggings’ – collected by Rona Bailey from Geoffrey Butterworth, Westport (chorus) and Janice Fleming, Westport (verses and melody), 1956; words originally by Charles Thatcher, chorus music reconstructed by Neil Colquhoun; public domain.”

Multi-instrumentalist Robbie Laven gave the album a rich palette of sounds, said Bollinger.

These songs are appealing and have longevity because they are straightforward, easy to sing alone or with others, relate basic concerns or pleasures, and tell a good story. There are songs of love and sorrow, parodies, lonely goldminers (“As slow the years of life steal on/ And turn the hair to frost”), topical news, such as Colquhoun’s ‘Murderers Rock’ song, commissioned by the NZBC for a play (“Dick Burgess, Kelly and Philip Levy/ That now stand trial in the dock/ They butchered poor Mathieu and friends/ For their gold, at Murderers Rock”. Others relate land grabs from Māori, the formation of unions, shearing, or about characters such as Joe Pavelka, jilted lover, thief and arsonist of the 1900s. Side by side with the CD they add 3D witness-account colour to bare facts.

Michael Brown, who wrote a comprehensive section on folksong-collecting from 1955 to 1975 in his 2006 Victoria University MA thesis titled There’s a Sound of Many Voices in the Camp and on the Track, provided the foreword for the 2010 publication. Of Colquhoun’s original version he wrote: “Of all the local song anthologies, it made perhaps the boldest statement of how folksong could illustrate the historical roots of a New Zealand identity.”

--