Originally written for the anthology Kiwi Rock Chicks, Pop Stars & Trailblazers, edited by Ian Chapman (HarperCollins, 2010).

Music was just something I’d always done; I never really thought of it as a career. My parents were both musical. They always insisted that my brothers and sister and I learn instruments, and between us we covered the piano (all around), trumpet, cello, clarinet, flute and bassoon, as well as guitar. I never really appreciated it at the time, but the classical training taught me a lot and developed my ear.

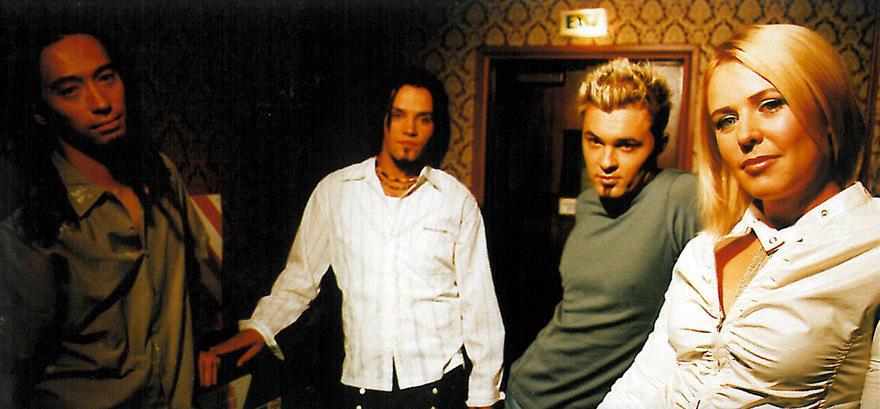

Tadpole publicity shot for The Medusa, 2002 (L-R): Chris Yong, Shannon Brown, Dean Lawton, Renee Brennan

I’d always sung, but I really wanted to be an actor, and until I joined a band that was my ideal career. At Auckland University I joined the Theatre Workshop club, and got a part in a Summer Shakespeare production of As You Like It, which involved some singing. That led to getting into Tadpole, and, once I’d tried my hand at songwriting and performing things I’d written myself, music basically took over my whole life. I’d always loved performing and forming a connection with an audience, and the whole team camaraderie of being part of a show, but music allowed me to flex a more creative muscle, with the writing on top of all that.

When I joined Tadpole I had no idea whether I could actually write, but I was 20 and didn’t have a clue that there might be things I couldn’t do. I just went ahead and did it, and hoped for the best. I guess it really does run in the family; my brother Matt is AKA Flick, he sings and plays in Cosmic Rays of Death, and my brother James plays guitar for Collapsing Cities. My sister, Antonia, is musical, too, but very sensibly chose a career from which she could actually earn a living.

The very first show I performed with Tadpole was at one of those five-bands-for-five-bucks nights at Auckland’s Powerstation, and the place was nearly empty. The Powerstation is a cavern at the best of times, but with no one in it, it’s pretty dire: the view from the stage is just a gigantic black hole. There was practically no audience, and I’d forgotten most of the words to the songs, and couldn’t hear a thing through the on-stage monitoring system. So we – in all honesty – probably sounded like crap.

But I had never felt quite such a rush, and I was hooked. Singing still remained something I considered my favourite hobby for years, but it took ‘Blind’ getting played on Channel Z in 1998 (four years after I’d joined the band) for me to start thinking of it as more than just what I did with all my spare time.

The Headless Chickens were my favourite local band: I loved Chris Matthews’ black comic take on the world, and Fiona McDonald’s stunning and powerful voice. There were international bands that I loved, too, but the Headless Chickens were a band I could actually go and see play, and it was their live shows that really made me wonder if I could do it, too. I was heartbroken at the Big Day Out gig (1995?) when Fiona announced she was leaving the band. I remember watching that show and really wanting to be up on stage – it was the first time I’d really consciously thought that I could do something like that – and then literally five minutes later Fiona announced it was ending. Until I discovered the Chickens, music was really something that was made elsewhere, that came piped through the radio.

Tadpole, 2002 (L-R): Chris Yong, Renée Brennan, Dino Lawton, Paul Matthews

I found being a girl in a male-dominated industry mostly an advantage. It made you memorable: band boys can blend into each other, with the same uniform of jeans and shaggy T-shirts, or T-shirts and baggy jeans. They are all called Steve or Dave. They all do interesting things with their hair, which strangely enough results in rather identikit appearances. Being a girl just kind of breaks up the band photo, and you can do far more interesting things with clothes.

There were some not-so-nice sides to it. Even though New Zealand is a small industry with very little in the way of hard cash worth competing for, there was still pressure to be thin, and I always felt like I was being judged as much on how I looked as how I sang, performed and wrote. Depending on what my hair colour was in the early days, we’d get reviewed as sounding like No Doubt (when I was blonde) and Garbage (when I was redheaded). It used to drive me nuts that people listen so much with their eyes, and that’s just getting worse.

I had my feelings hurt early on when we had recorded our demo version of ‘Blind’ and it was getting a bit of radio airplay, and I did the rounds of record companies. We were turned down by everyone, and word got back to me that a certain executive at Warner Music (who shall remain nameless) had said that he would have been interested in signing us if I wasn’t overweight. When I look back at the video we shot for ‘Blind’, I wasn’t overweight at all, but at the time I really took it to heart.

In the early days, before anyone had heard of us, I did have trouble getting into bars from time to time. There was a memorable occasion on my 25th birthday: we were playing a gig in Whangārei and I’d been in the bar sound-checking with the guys, but went out to get some food. When I came back to the bar the bouncer had arrived, and he wouldn’t believe me when I said I was with the band. He thought I was some hanger-on and wouldn’t let me in without buying a ticket. I had to call the guys to come down and rescue me. Bizarrely, he believed them when they said I was the singer, but not me.

I also learned the hard way not to wear strapless tops on-stage once we had stage-divers jumping up with us. Nuff said.

The other thing is that a life on the road is not easy, for anyone. It’s long hours, no sleep, and living out of each other’s pockets, and on most of our tours I was the only girl member of the crew. I’m not sure if being a girl made touring any worse for me than it was for the others, and for the most part I really did enjoy being one of the boys. However, by the end of the tour I was always a little over fart jokes, farts, travel farts and porn. I could really have lived my entire life without ever needing to know what top-decking was (don’t ask, but there are some motels that I’m sure would never have us back).

It’s been a hard path to choose in a lot of ways, but there have been some amazing, unexpected rewards

I’d always come home, ditch the boys, and hang out with girls for a few solid weeks (and shower twice a day) until I felt human again. However, I learned lots about how guys view relationships. That was a real eye-opener. I think they forgot I was there half the time, and I heard just about everything.

It’s been a hard path to choose in a lot of ways, but there have been some amazing, unexpected rewards. I’ll never forget how I felt the first time I heard one of our songs on the radio. Or the experience of recording our first album out in Karekare. Or how it felt to play to 60,000 at the Big Day Out 2000, having Coldplay go on-stage before us, and Fred Durst watching from in front of the security barrier. I’ve met Marilyn and Shirley Manson. I’ve gotten in to see so many amazing concerts by both local and international musicians.

I’ve seen New Zealand in a way that not many people get to see it. We met people who wanted to hang out with us in every town, who showed us stuff that only locals know about. I’ve had the experience of flying in a Hercules to East Timor, and spent three incredible days hanging out with the New Zealand Army, and getting a peek at what goes on in a peace-keeping mission. I qualified for my professional race-driver’s licence and raced on the Pukekohe racetrack. I’ve jumped out of planes for a radio competition. I caught a shark in Greymouth. We played a Christmas party for the SAS, and I can’t even tell you how they paid us; I would literally have to kill you.

I was asked to sing with my heroes the Headless Chickens, and played a Big Day Out with them (scared witless the whole time, because Fiona was watching from the sound desk). I got to be on the radio, and was given my own show, and then got to make a telly show as well – Sing Like A Superstar for TV3 – which for me felt just like being back at high school and doing the school musical. There are too many experiences to list all of them – it would take a whole book to do it justice, and I may want to write that myself one day.

That’s the trouble with massive highs. Ask any manic-depressive and they’ll tell you they are accompanied by massive lows. Band in-fighting, all our gear being stolen, good friends quitting the band, getting ripped off by concert promoters and venues. Breaking up with our drummer after nine years together, and still struggling to hold the band together for two more torturous years.

I remember early in our career, Joe Lonie, who directed our first three videos, sat us down before shooting ‘Blind’, our first music video. He said he couldn’t make a video for a band that had never watched the film This is Spinal Tap, so we dutifully sat down with him and watched it. It was hysterical, pathetic, and also strangely prophetic. Pretty much every single thing that happens in that movie has now happened in my life, including getting lost in a venue on the way to the stage. (The one exception is having the drummer spontaneously combust.) The thing that struck me most about that film was how sad it was that these real semi-talents could work themselves into such a tizz about their non-existent career. At the low points, you ask yourself if that isn’t an accurate reflection of your own life.

Renee Brennan and Chris Yong, Big Day Out 2001 - Chris Yong collection

To be a musician you have to have an incredible amount of self-belief, but I think all of us harbour a sneaking suspicion that we are not any great shakes. The saving grace of being a band rather than a solo artist is that you feel that, at least if you are suffering from career delusions, it’s a mass hallucination: there are three or four other people suffering the same delusion. When there is in-fighting in a band, though, it hurts worse than fighting with your best friends, because you not only put your friendship in jeopardy, you also put your heart and soul in the form of your belief in your band on the line, too.

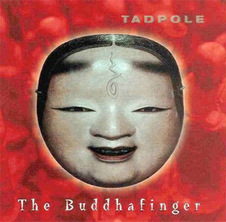

Tadpole's double platinum selling album The Buddhafinger (2000), produced by Malcolm Welsford at York Street Recording Studios.

I’m most proud of our albums. I’ll always have those to play to my grandchildren, although chances are they’ll hate the music! And I’ll always remember the night we won our first (and only) award. We were passed over so many times at the New Zealand Music Awards that I’d gotten used to not winning anything. I was out of the room when they announced that we’d won the Juice TV Best Independent Music Video award for our single ‘Too Hard’. I ran back in just in time to get to the stage and pick up the award, and then promptly forgot to thank New Zealand On Air who funded us. Idiot. (Brendan, by the way a belated thank-you – but you knew that!)

With the benefit of hindsight, it would have been much better if we’d made a lot of money from music. If I went back and did it all again, that would be the one thing I would change.

I think things are slightly better for performers today; the past 20 years have been a bit of a renaissance for musicians in New Zealand, I think largely thanks to New Zealand On Air. Musicians don’t really need to earn money from music, they just need the opportunity to make it, and an outlet for it, and they will keep dreaming up wild and wonderful things. With little financial gain in the New Zealand music industry (at least for most artists), there is very little pressure on commerciality. I firmly believe that New Zealand artists are lucky not to have much of a financial pay-off, because there is no temptation to make music to do anything other than to please yourself. I think that’s why we have such unique artists coming through. Having spent the past four years in the UK, I think we see far more variety in our small industry in New Zealand, because the industry itself is able to exert far less pressure. When my brother James was staying with me in London he joked about the UK sound, which the Collapsing Cities guys called EOBB. “What do they sound like?” “Oh, Every Other British Band.”

In terms of being a woman in music, I think the challenges are still there: you have to be a particular type of person to be able to tough it out with the boys on the road; that lifestyle really isn’t for everyone. But the rewards are there, too. There are still far more male musicians, so those women who do get involved are still a rarity, still unusual and noteworthy. There have always been great role models to follow: for me it was the Fiona McDonalds, the Annie Crummers, the Jenny Morrises and Shona Laings. Hopefully Boh and Bic Runga, Julia Deans and the others of my generation of musicians have provided inspiration to those of the next. It’s not an easy life to choose, but for those with the guts to try, it’s an amazing choice to have made.

I went to a careers day at my old high school, Baradene, several years ago. All the former pupils were sitting at desks with signs on saying your name and what your job was. I was sat there with all the lawyers, accountants, doctors, and professional people, and mothers were looking at my sign (which read “Musician and DJ”) and carefully shepherding their daughters away from my table.

But to the ones who made it to me, I think I managed to give good advice. I told them to think long and hard about whether music was something they wanted to do, or if it was something they needed to do. There is a difference, and those who just want it are the ones who fall away early. It’s only those who can’t not do it that will make it through. Know why you are doing it. Are you after money? You won’t get it. Fame? Bad reason: we don’t really do well with fame in New Zealand. Either it doesn’t exist, or it massively backfires on you. Know that it has a sell-by date: women at 40 in rock and roll (or hip-hop, or anything but jazz really) are few and far between. Have a back-up plan, train in something else, and work part-time (you’ll need to anyway). When you finally realise that music isn’t going to keep you warm at night or pay your bills, you’ll be glad to have something else to fall back on, but if you are anything like me you won’t ever give it up as a lifestyle choice.

Music will always be a part of my life. However, I have more of an emphasis now on my day job, currently working at an events production agency in London. I love living in London and travelling throughout Europe and further afield. I plan to be in London for the foreseeable future, but have definitely not ruled out coming home to New Zealand. For one thing, I miss the music scene there!

--

Renée Brennan returned to New Zealand. After reading this article again, in 2024 she wrote:

This was first published in 2010 in the Kiwi Rock Chicks, Pop Stars & Trailblazers book by Ian Chapman. When Ian sent me my copy after publication, reading it in London not only made me proud and nostalgic for home and the music, but also made me see the one thing I would change about those days if I had my time again.

The stories of the other female artists were so familiar to me, no matter the style of music they created or the decade they were working in, we all had these unique but still very similar experiences and reactions. We may have been trailblazers in the New Zealand music industry, but to a great extent we were individual comets. If we had only been more connected to one another, we could have provided each other with so much extra support, and made the great journey less lonely.

--