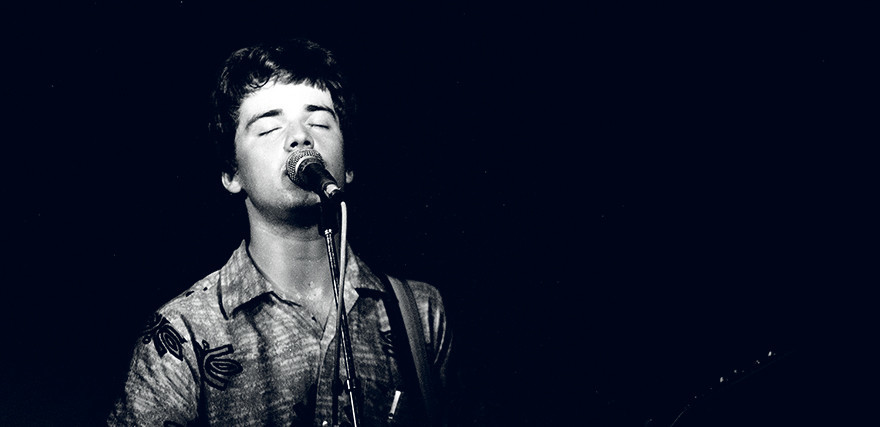

Martin Phillipps photographed on the 1984 Looney Tour, venue unknown. - Photo by Terry Moore

I interviewed Martin Phillipps several times during his final months, for a project he was helping me with. The last of them was on 20 June 2024, five weeks before he died. Our conversations amounted to four hours of recordings in which he ranged across his songs, his awkwardness on stage in his early years, to his place in the Dunedin music community stretching back to the 1970s, and his enduring friendships and “friendly rivalries” with his fellow songwriters in the city. This is part one of a series of three articles for AudioCulture from those interviews.

From his earliest songs, Martin wrote about the pressing issues of the human condition, and on his list from the outset was our mortality. He was made very of aware of his when he contracted hepatitis C and by the time he was in his fifties he had lost 80 percent of his liver function. In these interviews, I had the feeling he was talking for posterity as much as for the present. He spoke with great enthusiasm about what he and his generation of songwriters in the Dunedin music scene and around the country had achieved.

--

I guess you’ve been doing some reflecting on your own career and what grew out of Dunedin in the 1980s ...

Martin Phillipps: It’s one of the most extraordinary scenes I’ve heard about for a population this small. We’re acclaimed as the Dunedin Sound and the wonderful alternative music that happened right throughout the country around that time. We’d drive through big cities in the US with a population bigger than New Zealand and they’d hardly produced any bands. This little university town of 100,000 produced this music which, nearly 50 years later, is still resonating and shows no signs of stopping. In fact, it’s gathering momentum. I think a lot of that music resonates better than it did back then. There are a couple of reasons for that. New Zealand was always at least two years behind the times, relying on three-months-behind Melody Makers. By the time we were discovering our version of 60s garage meets post-punk they were already, in Britain, past Joy Division. It was like we were frowned upon right from the start as well as some people liked us. The weird thing is musicians don’t often compliment each other when they’re young. It’s only recently that pretty much all the major bands in Britain were admirers of the Flying Nun scene, but they wouldn’t say that to us (laughs), if they talked to us at all. Manic Street Preachers, Primal Scream, Stones Roses I think, probably Blur.

If you think back to when the Dunedin scene was happening in the late 70s, that was an interesting time with the clash between disco and punk. There were clear battle lines ...

I was a bit scared when the punk rock thing came along, because I’d go with some friends to a disco watching everybody beating each other up, and next week go to the Beneficiaries Hall and see The Enemy. I took one of my close friends who was more of a disco guy and he said, if that’s punk rock I don’t like it. I walked away thinking, no, that was great! I mean honestly seeing The Enemy playing some of those early songs and going, fuck those are great powerful melodies and if that guy had come off the stage I would’ve run out the door. Knox, yeah. I remember watching them setting up on stage and I thought that was someone’s dad, then he started singing and it was fuckin’ hell. No, it registered, absolutely changed my life.

The Dunedin scene was pretty hardline about what sort of music was acceptable or not, some of that felt like it was down to Chris Knox who was mighty opinionated ... and vocal about it!

Yeah, although it’s weird, he was a big ABBA fan and quite outspoken about them and Kiss as well. Kiss Alive was one of his favourite albums. He was a strange mix but I remember having a big argument with him at a party about, y’know, the Chris Knox sneer, when I was talking about going to Australia. Chris was sneering at me, and I just got sick of it, and I said Chris, how do you know anymore? It was eight years before we went to Australia and that was largely because of the Toy Love experience there. It was the best thing that we did: hold off until we had a reputation and bypass those gruelling small pubs. To his credit, Chris suddenly turned a bit humble and said, no, you’re right.

Often if you stand up to someone and challenge them.

Yeah, at school – Logan Park High – sometimes it was difficult to traverse the corridor without being assaulted by the bullies. I remember one time there were three of them lined up on each side of the passage on the way to the library. They were all bigger than me, but I picked up the first one by his throat and pushed him against the locker almost off the floor – “You say that again ...” – and he just backed down, and his friends. It was probably the first violent act I’d ever done but I’d absolutely just had enough of being bullied right through school. It took them like three seconds to realise, oh you don’t mess with him anymore.

Once you got cool factor you wouldn’t have been bullied anymore.

The thing is, the next year was probably fifth form or sixth form, at which stage most of the bullies had left to become apprentice mechanics, and people knew I had an electric guitar, so all of a sudden the whole thing changed: “He’s actually a bit cool now.” (laughs)

Speaking of those days, I hear you’ve discovered some Chris Knox artwork dating back to when The Enemy lived in a house down the north end?

Yeah, two of the big wall paintings that Chris did when The Enemy lived in their first house up in Warrender Street, down by George Street Normal School. I didn’t know The Enemy when they were living there, but I’d heard about the paintings and I went in there when the floors had been ... you basically had to walk on the beams. A friend gave me a warning that the place was being torn down, and I managed to contact the contractor and asked him to save some of the artwork which had been there for more than 20 years. We’re offering it first to the Hocken Library. They’re both pretty amazing twisted Chris Knox-kind of pictures.

It’s great you saved them – that’s the archivist in you, Martin. You have such a extensive archive of memorabilia including from the Auckland punk scene of 79, when you were, what, 15?

I thank my parents for this, they trusted me and they dropped me and a friend at the highway out of Dunedin in 1979 and I hitch-hiked my way to Auckland. I saw Proud Scum, Toy Love, The Primmers, Marching Girls, the end of the Auckland punk era, just as AK79 came out. I bought one of the first copies. I slept with cockroaches and had some pretty epic acid excursions and experiences in 1979 at, what, 16 years old (laughs). It was great. Then it’s back to Dunedin: the job’s not working, let’s put you back in school. Yeah, right, that’s going to work. I’d seen too much already, I deliberately blew it, my education. No, I’d seen through it. It was too late, I’d been corrupted by rock’n’roll.

Once that Dunedin scene got going there was a rivalry to write the best song – and that’s continued ...

There would be key people that have battled the most in a wonderfully friendly way for forty years, Shayne Carter, Martin Phillipps and David Kilgour. Graeme Downes too. That last Verlaines album, Dunedin Spleen, that’s a work of genius, it is fantastic.

You’ve all got your own distinctive styles. Maybe you’re seen as more the pop traditionalist, who wanted to get into the big studio and realise your particular sound ...

I’ve been out of sync with the Dunedin music community all along because there’s something different about The Chills in the way of approach that I’m not ashamed of, but I’m not prepared to go back down that “let’s try and capture it on 4-track” mentality. For a lot of people they’ve never got beyond that, and I sort of admire that and it’s beautiful, but it’s not us. We have this sort of tentative connection, and among those people they’re proud of what The Chills have done, but there are others that resent that they have to live up to something other than the natural beautiful music they want to make. I’m sorry about that but we have to follow our own path. It was just establishing our own ethos and it worked for both parties. Whenever The Clean would invite me on stage to play it was always special. The funny thing is I would always bring something different out of The Clean by my presence. There’d be a bit of tension, like, “We have to up our game a bit because Marty’s here” [laughs]. You could feel it and we’d have fun, it was great.

I talking with David [Kilgour] yesterday about how for two or three years I lived literally a stone’s-throw away from him. I could’ve thrown a stone onto his roof, because I was in the house next to his on the next street up, Cardigan Street. The point being that living that close, we’d only see each other maybe once every six months or something, y’know “Must have you around for dinner” became the catch-phrase, which is still going on. You maintain that closeness anyway. A lot of things don’t need to be spoken at this age, it’s there and [a] shared experience, there’s somebody who understands and I can relax. It’s the same with Shayne now, too, because of all my peers obviously Shayne and I are the most competitive. We’ve had the most similar stories in terms of Chills/Straitjacket Fits, being signed to international labels, going through very similar paths, even some of the same people. We’re always amicable but it’s really only in the last few years that we’ve been able to sit back look at each other and talk about it. The pressure’s not on anymore to be who’s best. We’re older and wiser.

One thing I’ve noticed Martin, is how well your voice has held despite whatever health issues you’ve had. It’s still very strong ...

More and more as I’ve gotten older, people say they’ve responded to my voice and I don’t quite get that. I think they mean the words but no, it’s actually the sound of my voice. It sounds like I’m speaking to you, that’s what they tell me.

A friend of mine, Ken Double, who wrote the New Zealand music column for the Listener in the 80s for a little while, says unlike some of the other Flying Nun bands you’re never in doubt about what a Chills song is about ...

Oh, okay, that’s a good comment, I like that. Sometimes I don’t realise until ten years later how frank I’ve been about something, and I go, Oh my God I can’t believe I said that. At the time it just seems like rock’n’roll lyrics, just spit it out. Sometimes I don’t even know it’s so personal, it slips by and it registers with other people who’re going through that same kind of issue, and they don’t forget that someone else was here singing about what was important for them at the time. I’m meeting more and more of those people now who’re older. Someone going through a bad break up, or someone had just died and it’s meant so much to me.

Music, reading, poetry, painting they’re the bulwarks against loneliness. All the arts are there to nourish and make us feel part of something greater than ourselves.

Yeah, and when you find a connection through an artist it’s like a new friendship.

--