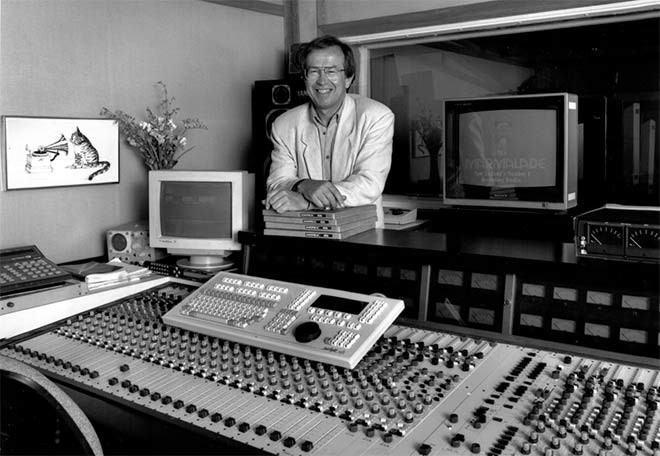

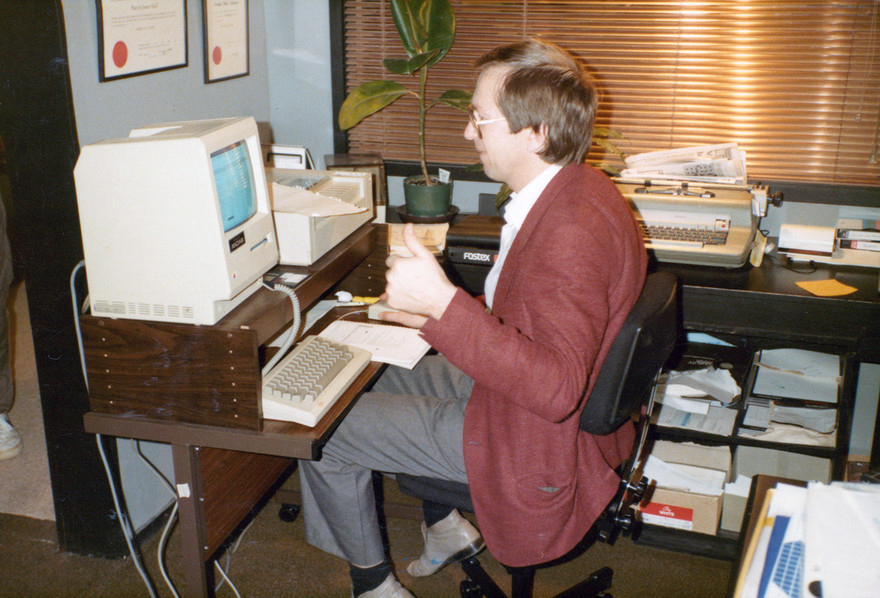

Rocky Douché in Marmalade Studios. - Rocky Douché Collection

From a teenage start in radio, to founding the country’s first 24-track studio, with involvement in the careers of stars such as Shona Laing, Sharon O’Neill and Jon Stevens, plus staunch advocacy for local quotas and efforts to take this country’s music to the world, Rocky Douché has – over six decades – been a gently persistent presence in New Zealand music.

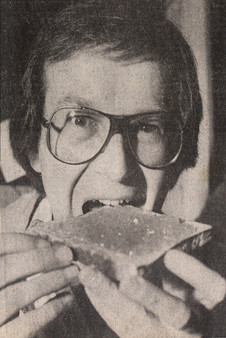

Rocky Douché: the name sounds like it belongs to a professional boxer or, at the very least, a celebrity DJ – not the bespectacled, slightly built, and mild-mannered subject of this profile.

Rocky Douché celebrates the launch of Marmalade's record label, Toast.

In fact, Rocky Douché did start out in radio, though his role was always behind the scenes. And yet anyone who listened to commercial radio in the 60s seems to know the name. How come? And where did the name come from anyway?

He was born Roland Douché in Bristol, England. When the Second World War was in its final phase Roland’s father, a technician, was from New Zealand to England to install radar systems. After the war, the Douchés returned to New Zealand and moved into a new state house in the Lower Hutt suburb of Taita. Roland was a foundation pupil at Taita Central School and later Taita College.

The family couldn’t afford university, but when Roland left school in 1959 his father arranged an interview for him with the chief engineer at the New Zealand Broadcasting Service. He was taken on as a technical trainee, but he quickly realised that his real interest was in the production side of radio. It was during these early years in radio that the “Rocky” nickname was bestowed on him by broadcaster Mahi Potiki (who, in the 1940s, became New Zealand‘s first female Māori radio host).

“She went from Roland to Roly, which is my family nickname, to Roll, to Rock‘n’Roll, to Rock, to Rocky, in one jump. And it conjured up this image of, you know, this nine-foot tall Canadian lumberjack. And there was this weedy me! So people cracked up and it sort of stuck, and it rolled off the tongue as a name much more than, say, Bill Smith or Jack Jones.

In those days it was common practice for announcers to acknowledge their technical support staff on air but, as Rocky says, “my name just happened to be the more memorable one.”

After three years at the NZBS, Rocky headed across the Tasman for a spot of OE. Working as a technician at Sydney station 2UW, he had the honour of playing the first record in the station’s switch to a Top 40 format, the first Sydney station to do so. (The record was Mel Tormé’s ‘Cast Your Fate to the Wind’.)

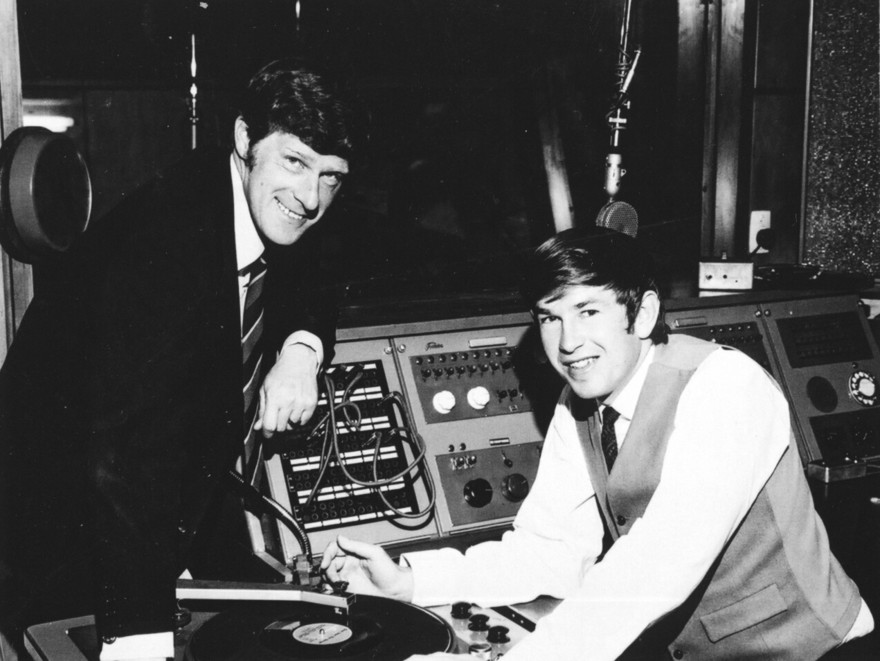

NZBC radio pop pioneers: host Neville “Cham the Man” Chamberlain and technician Rocky Douché

After a year in Sydney, Rocky was back in Wellington in time for the opening of Broadcasting House in late 1963, which would remain his home base for the next eight years. Although the purpose-built four-storey facility housed all five Wellington radio stations – 2YA, 2YC, 2ZB, 2YD, 2YB, as well as the shortwave station Radio NZ – production was so busy that outside studios were sometimes commissioned. As producer for Neville “Cham the Man” Chamberlain’s groundbreaking pop show Gather Round, which broadcast on 26 station networks, Rocky often worked after hours at Lindsay Anderson’s private Hataitai studio.

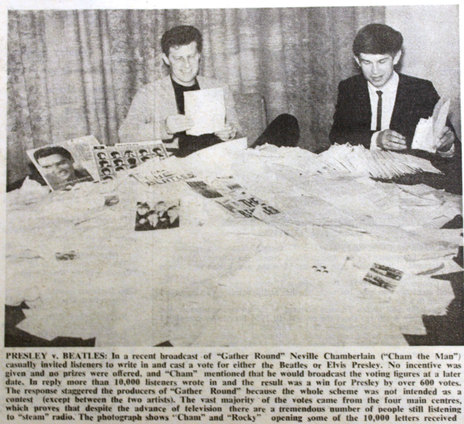

The results of a radio competition in Wellington in 1964. Counting the results are Neville "Cham the Man" Chamberlain and Rocky Douché who would later own Marmalade Studios.

In 1971 he resigned from Broadcasting and, after another brief spell of OE, this time in the United States, began to set up his own company, Marmalade. At first he focused on producing radio commercials – “because that’s where my skill-level rested, not really being a significant technical person like [Auckland’s] Stebbing brothers.”

Beaver recording 'The Biggest Love' with Bunny Walters, produced by Rob Winch at Marmalade Studios, Wellington, 1990.

An early coup was establishing a relationship with the Colenso advertising firm. “It was near the start of Colenso, and they were doing demos and doing pitches for new business, and I received a phone call one Friday night from [Colenso co-founder] Roger MacDonnell saying could I help them out? They had been doing some work at EMI to present to a new client on the Saturday, and at five o’clock they had been told ‘Sorry we don’t work later than five on a Friday’ and they couldn’t finish their presentation. So I turned out, we started recording at eight o’clock at night and we went on to about eleven or twelve. They won the client, and Roger said, we’ll bring all our work to you. So there was a slow shift of the advertising production work away from EMI as soon as I really got started properly with Marmalade and started competing head on with the commercial production side.”

Initially subletting the Kilbirnie sound studio of Pacific Films, by 1973 Marmalade had taken up residence in an upstairs floor of the Ascot Chambers building in Ghuznee Street. On the ground floor was the Sunset Strip, a late-night coffee bar with a reputation as an all-round den of iniquity and gathering place for Wellington’s denizens of the night. “Often when we were recording at night, we would have Korean and Japanese fishing boat sailors come up the stairs with a scrunched up piece of paper in their hands. They certainly weren’t looking for a recording studio!”

The studio’s first employee was Dave Ginnane, a young recording engineer fresh out of technical training at the NZBC. More interested in music recording than the advertising work that was Marmalade’s bread and butter, he left at the end of 1976 to work for EMI, though he returned to Marmalade in the early 80s and remained there for most of that decade.

Marmalade advertisement in Rip It Up, September 1979. - PapersPast

Alongside the studio, Rocky established Marmalade Artists, a management company to support and promote local artists. Initially this involved Rick Shadwell, A&R manager for PolyGram, who was having success with teenage singer-songwriter Shona Laing. After Shona recorded some demos for Marmalade, Shadwell took her to Japan for the Song Quest Competition, then to London where she acquired new management and remained for several years.

After the departure or Shadwell and Laing, Rocky hired musician Steve Robinson – formerly of Tamburlaine and then playing with The Heartbreakers – to run Marmalade Artists. An early project oversaw the transition of singer Steve Gilpin and his band Fragments of Time from pub-rockers to new wave band Mi-Sex, who would be hugely successful in Australia. Robinson also proved to be a talented jingle-writer and multi-instrumentalist, and along with artist management and music production he worked on commercials.

One night early in 1977 the Sunset Strip was bombed with a Molotov cocktail, a result of underworld rivalry. The whole of the Ascot Chambers building was affected. “Our reception area and office were wiped out”, Rocky remembers. “But the studio itself just had a bit of smoke damage, because when you build a studio you’ve built a soundproof and often an airtight environment and a fireproof environment. But we convinced the insurance company that the long-term ramifications for the smoke going through the equipment was bad because of contacts and things. So they gave us a pretty good payout and we relocated to the Trade Centre building.”

Rocky Douche at the new Macintosh, 1985. - Jim Hall Collection

Opened in the early 70s, Cuba Street’s World Trade Centre was built with a view to hosting trade fairs and had a large exhibition area designed for this purpose, however the original vision had not panned out. “And so there’s a big open space with a high stud and no windows, which was obviously not much use for renting out for anything else, that was perfect for a studio.”

Wellington had only one major recording facility at the time: EMI, which had recently relocated from downtown Wellington to Lower Hutt, where they now boasted a room large enough to fit an orchestra and 16-track Neve sound desk. Eldred Stebbing approached Rocky with the idea that Marmalade set up a 24-track studio, the first in the country. Rocky believes that Stebbing was motivated in part by a longstanding grudge against EMI, who had at one point been looking to set up an Auckland studio in direct competition with Stebbing. “He spooked them out of doing it, but he always had this chip on his shoulder that he would get back at them for even thinking about taking on the Auckland market.”

Southside of Bombay master backup including 'What's the Time Mr Wolf', from Marmalade Studios in Wellington.

Stebbing became a shareholder in the new Marmalade Studios, though quickly pulled out after a disagreement over studio layout, leaving Rocky the owner of a new 24-track machine, “and also the owner of some unscheduled debt, because we had a cash-flow shortage because of the lack of capital going in.”

Sharon O'Neill's Words and Jon Stevens' Montego Bay (both CBS, 1979) – recorded at Marmalade Studios.

Luckily there was plenty of incoming work, both commercial and musical. Not only was the 24-track facility an attraction to record companies looking to produce recordings that could compete sonically with the product from overseas, but the relocation of EMI to Lower Hutt had seen a slump in the veteran company’s production work. No one, it seems, could be bothered going all the way to the Hutt to record, however flash the studios. Longstanding EMI engineer Frank Douglas estimated that the move to Lower Hutt cost the company up to 80 percent of its clientele.

After recording her first album at the NZBC’s Broadcasting House studio, Sharon O’Neill came to Marmalade in 1979 to make the follow-up for CBS. This coincided with a visit to New Zealand by American producer Jay Lewis, who had been brought out by the Recording Industry Association to conduct a series of production seminars using local artists. First he produced Citizen Band’s album Just Drove Thru Town at Auckland’s Mandrill studio. Then he headed south to produce Sharon O’Neill’s album at Marmalade, on which work had already begun, with Steve Robinson producing the single ‘Words’.

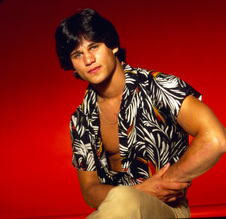

Jon Stevens in the late 70s

At the same time, Marmalade was developing a teenage singer from Upper Hutt who had been brought to Marmalade Artists by Wellington DJ Danny Ryan. Jon Stevens had been discovered by Ryan at a talent quest in Upper Hutt. “Danny came back to us raving about this young man who was very talented. Danny became involved with Marmalade Artists and we physically and musically groomed Jon for close on a year. We had him taking singing lessons and had someone looking after his appearance.”

Jon Stevens’ first single ‘Jezebel’ hit No.1 in early December 1979 and remained there until that Christmas. The follow-up, a cover of the Bobby Bloom song ‘Montego Bay’, reached the top spot the following January, and a month later a Jon Stevens/ Sharon O’Neill duet, ‘Don’t Let Love Go’, would go top five. Marmalade was becoming the home of the hits.

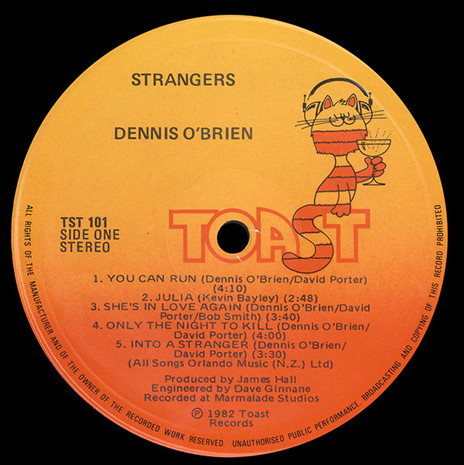

During this time it also set up its own record label, Toast, distributed by PolyGram. Though the label was short-lived, its handful of releases included a classy album by Dennis O’Brien, Strangers, featuring what was becoming a roster of Marmalade regulars: keyboard player Bob Smith, bass players Jim Hall and Clinton Brown, and singer/guitarist Steve Robinson.

Dennis O'Brien - Strangers (Toast, 1982)

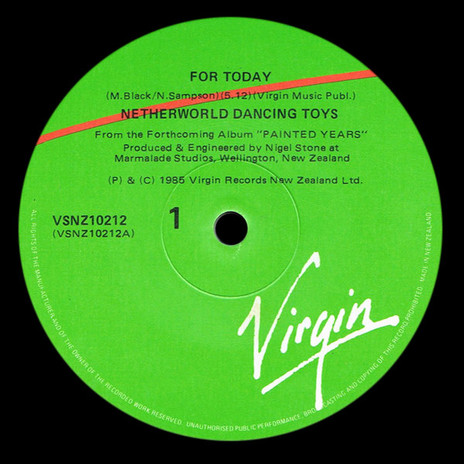

Through the 80s the studio would host numerous artists and turn out many successful records, some recorded by staff engineers Dave Ginnane and Simon Hughes, others by independents such as Nigel Stone, who produced and/or engineered such hits as Netherworld Dancing Toys’ ‘For Today’, Dave Dobbyn’s ‘Slice of Heaven’, the Holidaymakers’ ‘Sweet Lovers’ and Annie Crummer’s ‘See What Love Can Do’ at Marmalade.

Netherworld Dancing Toys – For Today (Virgin, 1985). Produced and engineered by Nigel Stone at Marmalade, Wellington.

Convinced that the best New Zealand music was the equal of anything from overseas, Rocky formed a contingent, supported by the QEII Arts Council, to represent New Zealand music at Midem, the annual international music fair in Cannes. Though three successive trips in the early 80s failed to secure any major international releases for local product, he was there with Dalvanius Prime when word arrived that, back in New Zealand, Pātea Māori Club’s ‘Poi E’ had reached No.1 – an extraordinary achievement given local radio’s reluctance to play it.

Since the 70s, the quantity of local music being played on commercial radio had gone into steep decline. By the mid-80s there was a radical deregulation of the radio market and very few local records were getting airplay at all. Though station programmers cited inferior production standards, in fact it was simply easier for them in this commercially competitive environment to follow overseas formulas. Rocky made a study of the amount of New Zealand music being broadcast – it averaged between two and three percent – which provided supporting evidence for a Private Member’s Bill, brought before Parliament by the MP Graham Kelly, to legislate for a local music quota. Though the Bill fell over, the quota lobby continued to gather momentum. Over the next decade various initiatives would emerge, such as the Kiwi Music Action Group and the NZ On Air Kiwi Hit Disc.

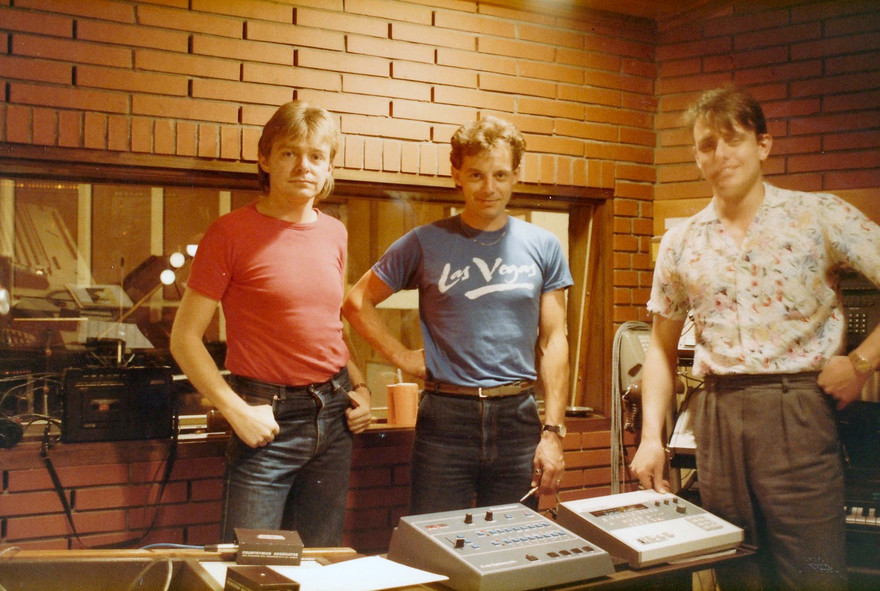

Jim Hall, Steve Robinson, and Ian Morris at Marmalade Studios c. 1984. - Jim Hall Collection

Meanwhile Marmalade was changing. In the 80s, Rocky had brought Dave Ginnane and Simon Hughes into the company as shareholders. With independent engineers such as Nigel Stone, Ian Morris and Tim Farrant now overseeing an increasing amount of the recording work, Ginnane moved away from engineering to take over much of the company’s day to day management. Steve Robinson left to form Soundtrax with Jim Hall, opening their studio and office just down the corridor from Marmalade.

The Holidaymakers' Sweet Lovers (Pagan, 1988) and Southside of Bombay's What's The Time Mr Wolf (Pagan, 1992) – both recorded at Marmalade Studios, Wellington.

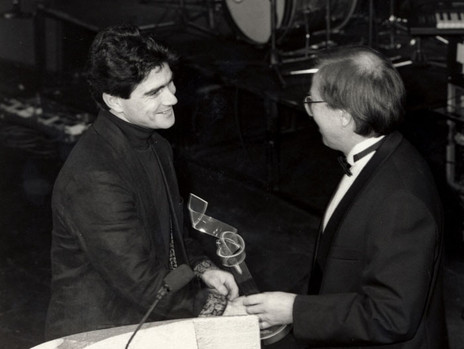

Toasting Marmalade: Nigel Stone and Rocky Douché at an awards event in 1993.

In 1993, Ginnane sold his shares to Hughes and headed to the UK to develop software. By the end of the decade Rocky had sold his remaining interests in Marmalade. The studio continued to operate until 2016, with Grant Taylor taking ownership in the early 2000s and his daughter Sarah taking over after Grant’s death in 2006. But by 2016, major changes in technology, music and advertising had made the studio no longer viable, and the company went into liquidation.

Rocky’s involvement in music didn’t end entirely with his departure from Marmalade. In the early 2000s he was commissioned by government agency Industry New Zealand to prepare a research paper on the New Zealand music industry, with a view to increasing its “economic energy”. The paper led to a workshop at which the major record labels were represented along with radio, television and NZ On Air. Rocky remembers the workshop as being a turning point, at which commercial radio, which had been vehemently opposed to legislation, conceded to voluntary quotas.

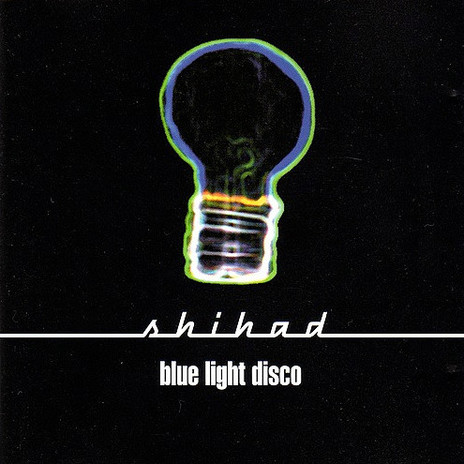

Shihad - Blue Light Disco (Wildside Records, 1998), recorded at Marmalade Studios.

“They set off, I think, to get to 10 per cent within a year. In actual fact they exceeded that. Once they started exposing [local] music to the general public, people started to like it. We had been told on many occasions by the radio industry that New Zealanders weren’t interested in hearing New Zealand music, the quality wasn’t good enough, et cetera et cetera. And they were also concerned about losing market share. They didn’t want to break ranks. We’d always predicted that, from the way the quota system had worked under the Whitlam government in Australia and how that really got the music industry up and humming big time, that the same situation would happen in New Zealand. And so the model was there. So in New Zealand I think it went from two or three per cent across the board to something like about 15 percent in the first year. And then within two years it was up to about 22 or 23 percent.”

Fur Patrol with Rocky Douche of Marmalade Studios, Wellington. From left: Julia Deans, Simon Braxton, Rocky Douche, Allan Clark, Steve Wells, and Andrew Bain.

But if some 40 years involvement in local recording seemed to have culminated in this flourishing of New Zealand music, Rocky couldn’t foresee the changes that would subsequently occur. As he says today: “Since then, technology has moved on and the radio industry is not needed now to promote New Zealand product, but the fact that the artists haven’t really got a vehicle to make a living from music is the big worry. We’ve actually gone back to pre-quota days, in a sense.”

Since moving out of the music business Rocky has worked as a business mentor, though at 81 he now considers himself retired.

--