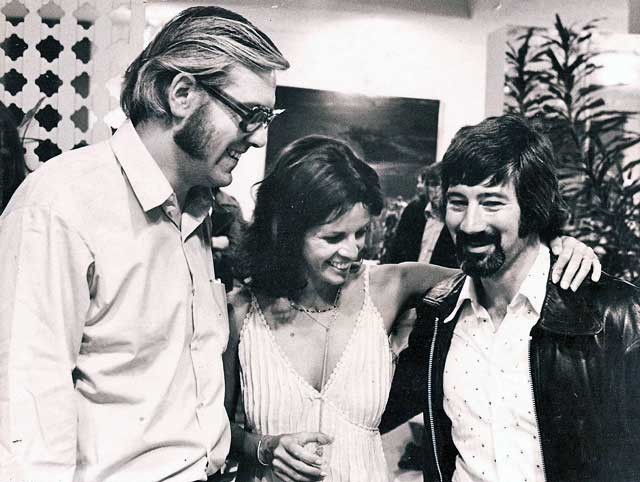

John McCready with AJ Morris, Managing Director of Phonogram UK, and actress Claudine Longet (then wife of Andy Williams) LA 1974. Phonogram had just done a deal to distribute Andy's label Barnaby in the UK.

Getting to do your OE in London while working as a well-paid music executive sounds like a great idea. When I sat down to speak to John McCready about his overseas experience, he had quite a bizarre story to tell. He was there for three years and worked at three different companies – his story packs a punch or two.

Working for a large company does not seem that easy. In late 1973 when Polydor UK wanted John McCready to leave his MD job at Phonogram New Zealand to move to London to be the marketing manager, the head office of Phonogram said, “No, you can’t go to Polydor, you have to go to our company in the UK.”

McCready was then offered the marketing job at Phonogram London. He accepted the position but when he got there he was in for a surprise. “Head office was forcing me on them. The job they gave me was National Sales Manager. I’d been duped. I said I am not going to do it. It’s not what I am good at.”

McCready and his boss, AJ Morris, were put on a plane to HQ in the Netherlands to sort the matter out. It was decided that McCready would run the A&R department. Suddenly he was A&R director of one of the four biggest labels in the UK. The biggest act was Status Quo who were selling several hundred thousand units of each album.

When it was announced in Billboard (15 June 1974) that Phonogram UK was restructuring to foster internal competition and autonomy for its individual labels, the magazine noted: “Masterminding the operation is John McCready, recently brought in as general manager of the company's creative division.” Reporting to McCready were six label teams, each with its own label manager, promotion man and press officer. The magazine noted that McCready’s strategy had been successful in New Zealand.

Meanwhile, Status Quo were in the studio and no results were evident. McCready had to drop by the studio. The band were drinking beer and listening to and laughing at the Troggs tapes. McCready then had to do his company plea: “Come on guys you’ve been here a week, it’s costing us £200 an hour and no music is coming out. A week later we had an album.”

McCready had A&R legend Nigel Grainge assisting. Grainge was known to like Irish acts and Thin Lizzy had left Decca so signing them was a no-brainer. They broke big in the UK immediately but McCready recalled, “The first Mercury album could not get a US release. Seymour Stein from Sire Records was saying ‘I’ll do anything to get this band’ but head office would not release it. Eventually head office forced Mercury USA to release the album. The next Mercury album included the track, ‘Boys Are Back In Town’.

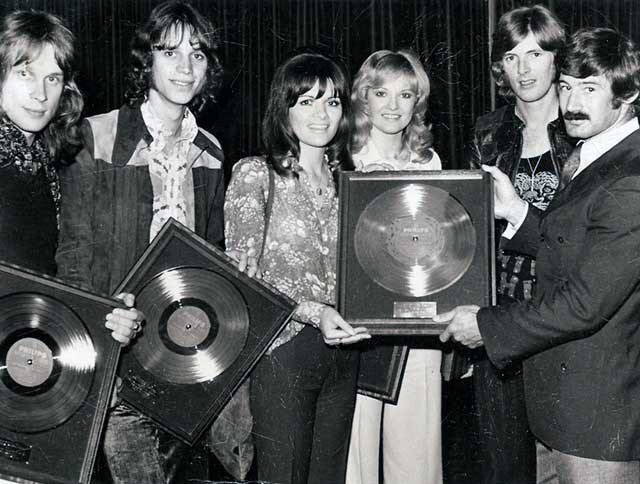

John McCready with The New Seekers and their manager David Joseph during the 'I'd Like To Teach The World To Sing' period

Antipodean Aptitude

In England, McCready found that New Zealand had been the perfect training ground for working in the UK as the mother country was behind in marketing via radio and TV and staff were often inward-looking and specialists in narrow facets of the music business.

“I had the advantage that In New Zealand we were ahead of them in marketing – we’d had private radio for a few years, we had commercial television,” McCready told AudioCulture in 2014. “When I went to the UK in 1974 no record company advertised on radio. Capitol Radio had just started and I started advertising recordings on Capitol Radio and I did the first TV advertised album. After I left Phonogram, Nigel Grainge did a Stylistics compilation on television and picked up my style of marketing and sold over a million copies.”

“In England, they were very inward looking. Not outward looking like New Zealand. We look out. They would never have signed a Kraftwerk album because it was from Germany.

“We had this broad experience they did not have – starting out at Philips in New Zealand, you did every job in the company – you did stock control, sales and marketing etc. In England they specialised, nobody had an all-round experience in the industry. Executives did not know how to make a record cover.”

McCready recounted his experience with Kraftwerk to NZ Musician (Feb/Mar 2015): “Our German company had an electronic band called Kraftwerk and they asked me to consider their new album for UK release. Florian and Ralf came to see me in London and played me Autobahn. I found the album and the group very exciting and agreed to sign them for the UK. However, on playing it to our sales and promotion people I received a totally negative response and the feeling in the room was that I had gone totally mad. It gave me great satisfaction in later months to see Kraftwerk’s Autobahn sell in the millions worldwide.”

Kraftwerk's classic Autobahn, signed to Phonogram (and released on their Vertigo imprint) by John McCready

Later that year, Billboard (14 September 1974) once again quoted McCready: “New Zealander John McCready told the sales conference that the aim was to improve quality by attracting artists to the company’s own producers rather than accept substandard talent through overall production deals with outside agencies.”

One of the production deals that McCready sought to terminate was with the manager of one of Phonogram’s pop acts, child-star Lena Zavaroni. His name was Phil Solomon and he was an Irish talent manager whose 1960s roster had included Van Morrison’s short-lived Them and The Bachelors. Solomon had also owned the sizeable indie record label Major-Minor (Dubliners etc) that collapsed in 1971 and he had invested in offshore pirate radio station Radio Caroline and sold access to the station’s playlists.

Solomon was contracted to receive an advance on each of the six singles he delivered per year, even though they were never hits. McCready’s boss AJ Morris agreed that the contract should not be renewed. Solomon took McCready to lunch, in his Rolls Royce, and over lunch, offered him B-side writing credits on future releases, as an incentive to renew the contract. McCready said no and had to find his own way back to the office.

Solomon responded by not delivering Lena Zavaroni’s album and McCready was instructed to inform him that Phonogram were taking legal action. During a large Phonogram A&R meeting a voice shouted, “Where’s that fucking McCready?” Solomon then threw a briefcase at McCready’s face and fists followed. Acting in self-defence, the athletic McCready threw the older man across the table to the floor. When he approached Solomon to see if he was okay, McCready was kicked in the groin. This was too much to take and McCready got Solomon in a headlock and marched him out of the building to cheers from Phonogram staff.

As Solomon was thrown down the stairs to his Rolls Royce, McCready’s bemused boss arrived back at the office. McCready wanted the police called while his boss wanted the matter hushed up. McCready told his boss that he could not work for a company that did not stand by him, when he had just been subjected to an unprovoked attack at his place of work. Morris suggested he go home and calm down.

In McCready’s own words: “Early next morning there was a knock on the door of our home. I answered it. A chap advised me he had come to pick up the company car. I gave him the keys. I phoned AJ Morris who told me he has issued a release saying I was no longer with Phonogram UK. Did I resign or was I fired? I am not sure. One thing that was certain is that AJ never wanted me on his team and he had taken the opportunity to get me out.”

To add insult to injury, when Phonogram was asked as to McCready’s whereabouts, they said he had returned to New Zealand. But Billboard magazine (28 September 1974) got his location correct: “General manager of Phonogram’s creative division, resigned last Friday. It is understood that New Zealander McCready proposes to stay in London.”

John McCready with The New Seekers

After 16 years at Philips in New Zealand, McCready was out of a job after only eight months. Phonogram International were understanding and wanted to give McCready a head office job in Netherlands but McCready did not want to move his family out of London, so he negotiated a financial settlement and became a free agent (unemployed) in London with a wife and four children.

Decca 1975

McCready was quickly offered the opportunity to join Australian-born record executive Ken East in the task of turning the conservative Decca label around as Pop Music Marketing Manager. Once again Billboard (14 December 1974) reported: “Decca has appointed John McCready as manager of the company’s popular marketing and promotion division.”

East had worked for EMI for most of his career and he was a popular MD at EMI London in the 1960s and in Australia in the early 1970s. McCready was surprised to find that Decca had different elevators and lunchrooms for executives, reflecting the traditional English class divisions. There were two executive lunchrooms, one specifically for the Decca chairman and invited guests.

If McCready took the wrong lift, he would hear an old man in a uniform say: “You must take the left elevator. That one on the right is for non-managerial staff.”

The Decca corporate headquarters, The Embankment, London

McCready wrote in his 2010 blog: “I entered the world of class division as advocated by the company’s founder and Chairman, Sir Edward Lewis. Being the son of a Wellington waterside worker I found my new ‘status’ very strange.”

“Dick Rowe, who turned down the Beatles but signed the Rolling Stones, he was still there,” recalled McCready. “All these old characters.” Decca’s past was rich, so they repackaged the hits of The Rolling Stones (Rolled Gold), Tom Jones and Engelbert Humperdinck as the first project. Another source of repertoire was from the USA, Al Green from Hi Records and The Chi-Lites from Brunswick Records. The Chi-Lites had five Top 10 UK singles between 1974 and 1976. McCready toured all the clubs with The Chi-Lites.

John McCready with The Chi-lites and BBC 1 DJ Johnny Stewart, 1975

At Decca, new managing director Ken East wanted to reduce the number of singles the company was releasing. Billboard (30 November 1974) reported that Decca had issued in excess of 300 singles in 1974, as their market share fell from 8.1 to 3.8 percent. “Quantity is no substitute for quality,” said East. Decca’s UK A&R had gone stale and they had recently lost the distribution rights to the American MCA label in the UK.

Like Phonogram, there was a need to get rid of non-performing outside production deals and to focus on the company’s own A&R. McCready soon found that Phil Solomon had the identical six single contract with Decca that he had with Phonogram. McCready delivered Solomon the bad news and East backed McCready up when the Irishman tried to protest the decision.

In McCready’s words: “A couple of weeks later Ken called me to his office where I met a friend of Ken’s who was a music publisher. This guy was brought up in London’s East End and was still in touch with old friends connected to the seedier side of the music business. He informed me that there was a contract out for me to receive a beating and a few broken bones. Of course Ken and I felt we knew who was behind this.”

East arranged for McCready’s car to be parked in the yard directly outside the office entrance and he did not go anywhere alone. A couple of weeks later East had good news. “His friend had discussions with East End contacts and a deal has been agreed,” recalled McCready. “I was off the hit list and safe.”

At Decca, East and McCready managed a remarkable turn around with success from former Moody Blues members, Justin Haywood and John Lodge and their album Blue Jays. In the summer of 1975, McCready signed John Miles from an unsolicited tape. He was paired with producer Alan Parsons and that year he had two UK hit singles: ‘High Fly’ (No.17) and ‘Music’ (No.3). In 1987 Miles became guitarist for Tina Turner and stayed with her throughout her solo career.

Ken East became frustrated with the Decca old guard led by Chairman Sir Edward Lewis, so he left Decca late 1975 to become the International President for Motown. East asked John McCready to became CEO of Motown UK and Director of International Marketing. McCready initially said no and wanted to perservere at Decca despite the restrictive heirachy. East kept the job open for McCready.

A month later McCready was fed up with the “progress prevention police” role of the old guard that caused a decline in staff-morale. When he tendered his resignation, the Decca Chairman Sir Edward Lewis stood up behind his desk, pointed his finger at McCready and shouted, “You are just like that East … you … you ... bloody colonials.”

Cannes Encounter

As an aside, 1976 started with East and McCready attending Midem music business market in Cannes, France. Sitting at the lobby bar of the Cannes Casino one evening, McCready saw a short stocky guy run from the casino pursued by a bigger guy who tackled him and they both fell on McCready’s table, smashing the glass. The big guy started to smash the short guy’s head on the floor. McCready restrained the bigger guy in a hammerlock as a young woman attempted to scratch the attacker’s eyes out. The gendarmes arrived and took all four aside. After a discussion with witnesses, McCready was released and the other three were taken aside and questioned.

On the plane back to London, the short stocky guy walked down the aisle from business class and shook McCready’s hand. “I’m Don Arden and I just wanted to thank you for intervening last night. If you hadn’t I could have been seriously hurt. If ever you need anything, give me a call, here’s my card.” The young woman in the incident was Arden’s daughter Sharon, now Sharon Osbourne.

In his 1999 autobiography Mr Big, Arden recalled the night in Cannes. “We were in the casino when we spotted Patrick Meehan [former Black Sabbath manager] at one of the tables. Sharon got the hump of course and started winding me up about it. In the end, just to shut her up as much as anything, I went over there and went off at Patrick again. Then this Italian guy he had with him – who I later found out had just done 14 years for murder – did a flying head-butt at me and knocked me sideways! So I went crazy, my guys jumped in, Sharon jumped in and the whole thing became like a saloon brawl in a cowboy movie: bottles smashing, chairs flying through the air, the lot.”

“It should have been scary but it wasn't, as I didn't have time to think before stepping in of necessity,” recalled McCready in 2015.

In later years McCready would have amiable interactions with Arden as manager of ELO. “I was invited to, and attended a party at his Beverly Hills home on one occasion, though I didn’t stay long, as it was just too wild and over the top for me.”

Motown 1976

In his new Motown role, McCready had to negotiate distribution licences in Europe and look after the artists when they toured. The latter role became time consuming, as most of Motown’s royalty toured Europe that year. If he wasn’t dealing with divas, he had to be on his best behaviour for Berry Gordy’s son-in-law, Jermaine Jackson.

When McCready and East went to lunch with Marvin Gaye, the singer talked about royalties and whether he was receiving UK royalties. Suddenly, a nearby diner started choking on his food and Gaye rushed to assist him. When the singer returned to the table, he’d forgotten the royalties conversation and they had a very pleasant lunch. “His concert that night at Albert Hall Concert was absolutely phenomenal,” recalled McCready. “A man at the top of his game.”

Stevie Wonder also toured his Songs In The Key Of Life album in 1976 and Diana Ross put the “d” in diva for McCready. “We were in Rome and she wanted to go shopping in Paris,” said McCready. “It took two hours to get her a jet. We then rang the manager and he said, ‘Diana’s changed her mind’.”

When the tour ended in London, McCready was told, “Diana requested nobody from Motown attend the end of the European tour party.” McCready had no way of knowing whether she did make that request. “Working for a big company – you just had to suck it up.”

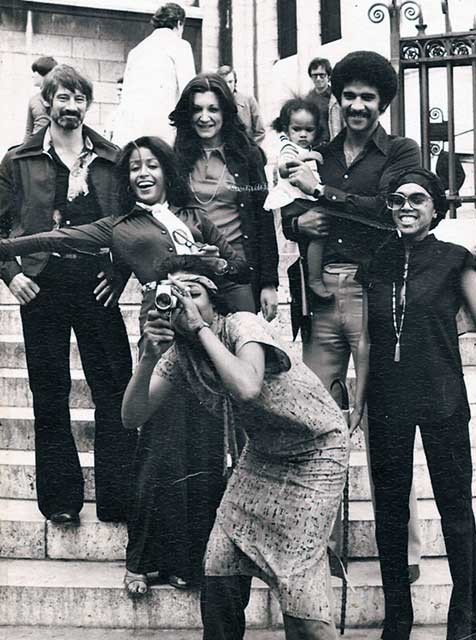

John McCready with The Supremes in Europe, 1976

When the post-Diana Ross Supremes led by Mary Wilson toured, they thought the UK Motown man, the white guy, could carry their luggage: “They treated me as their baggage boy,” said McCready. “It was strange working for Motown – I never saw any American executives except CEO Barney Ales, a white guy.” McCready enjoyed working with Ken East and Motown but he wanted to run a label, not to run errands.

Ales was the highly successful head of sales at Motown in the label’s heyday and he left to start the Prodigal label in 1974. Decca had the rights to the Prodigal label and McCready released recordings by Shirley Alston, the former lead singer of The Shirelles, while he was at Decca. In early 1976 Berry Gordy brought Ales back as Motown Executive Vice-President and purchased the Prodigal label.

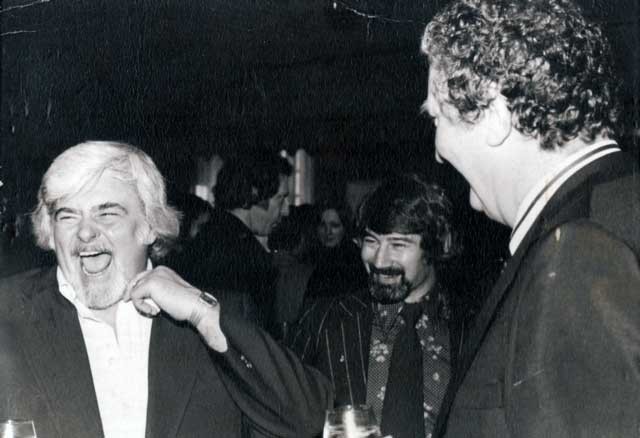

John McCready with Barney Ales, President of Motown, and Ken East, International President Motown, in 1976

McCready decided to return to New Zealand. Before leaving London, he visited Ken Berry at Virgin Records (Sex Pistols, Mike Oldfield) who he knew from dealing with the Virgin retail chain. McCready suggested that he could do a better job distributing and marketing Virgin in New Zealand than their current licensee, EMI. Berry who knew McCready when he was at Decca, was impressed with the concept and he offered him the rights to distribute the Virgin label in New Zealand.

--