Early on, Ian Magan identified that in the music business and concert production, it’s all about developing long term contacts. It’s a cliché but it really is about establishing a reputation for reliability and integrity. He toured Billy Connolly 14 times in NZ without even having a contract. A lot of the acts he worked with were concluded on a handshake deal. Later, the business got tighter and tougher legal contacts were the first step to a mutual understanding. But as Magan says: “It doesn’t matter how many legal contracts you sign, you still rely on your personal association with the artist or artist management, or both, to make it work.”

A lot of tours were concluded on a handshake deal.

Magan had some early interesting experiences with Dire Straits. He developed a very happy association over the course of three tours with the band, the last of which attracted the largest audience numbers for New Zealand ever. Auckland pulled 102,000 people over two nights, Wellington 48,000 and Christchurch an amazing 67,000 people. These audience figures still remain top sellers in Christchurch and Wellington, but the Auckland record was broken by Adele’s sold out shows in 2017.

He credits DJs such as Fred Botica for getting Dire Straits radio airplay and pushing them to mass popularity before any other country. The Cure was another band that had massive chart success here before any other country. Both bands had a high respect for New Zealand because they made it here first. Artists talk to other artists, and that word of mouth was pivotal in a flow of other acts wanting come further south than Australia.

After touring Dire Straits in 1983 – when they played to a moderate-sized crowd at Western Springs – Magan said “We knew this band was gonna fly.”

Dire Straits had already had their first hits by then, but in 1985 when they released the album Brothers in Arms – with the single ‘Money for Nothing’ – Magan instinctively knew it was going to be a massive album, and that their tour of 1986 was destined to be huge.

Dire Straits 1986 NZ tour, promoted by Ian Magan, who says, “We knew this band was gonna fly.”

“We knew the band well by this stage and I can remember sending them a message when they hit No.1 in New Zealand in a spectacular fashion. They were on their way flying to New Zealand from Australia and we talked some guy in Air New Zealand to send a message through to the captain of the aircraft to tell the band. The captain announced it on the inflight PA system that Dire Straits, flying with Air New Zealand, had just hit the number one album slot. So Mark Knopfler gets off the flight and his arms open and waving when he sees me at the airport, and he says, ‘How the hell did you do that?’”

That’s how you build relationships with musical clients. Magan acknowledges that not every artist will remain loyal to the promoter and might shop around for better deals, but in his case “… 80% of the artists I’ve worked with are repeat business”.

Researching the potential of a visiting artist is conducted by going to local music heads around the country, music journalists, radio DJs, many of whom Magan knew, reviewers and record retail stores (a diminishing breed). And of course the record label.

Magan: “You’ve always got to assess the risk and we quite often make mistakes … and on occasion be 50, 60, $70,000 down the tube. It gets scary at times – yeah.”

So how does it work in terms of fees and the share of the gate? “Most artists these days, if it’s a big artist, they will allow the promoter to take a certain figure. It’s very carefully controlled. The Rolling Stones, I believe, and I don’t know this for certain, but I believe they allow the promoter to take about 2.5% of what he earns for the band in their country. Mick Jagger is a very smart businessman … musicians have become very smart business people over the years. The promoter’s role, in a way, has become less important compared to the rise of the musician. The musician now has the dominant role and the more business-like he is, the more dominant he will become.

“The promoter’s role has become less important ... the musician now has the dominant role.”

“U2 is another good example. They control and want to know every thing, right down to selling the merchandising and what and how much is it selling for … they want to know. But most of us [promoters] work on a sort of rough percentage of between 20-30% of the profit of a tour, which a lot of non-entertainment businesses would say is ‘unacceptable. That’s not enough – we want a 50% mark-up or we don’t even go out’. But you can’t do that now.”

Some of the other risks involved are the failure of an artist not turning up. “We’ve had a couple of those due to genuine illness,” says Magan. “We sold 72,000 tickets to Michael Flatley’s Lord of the Dance over seven nights at the North Harbour Stadium in Auckland a few years ago. But in Brisbane, on his way over to New Zealand, Michael Flatley fractured a small bone in his foot and he couldn’t dance and we had to refund 72,000 tickets – it was a very painful time. Luckily we had insurance to cover ourselves for that loss, otherwise I’d be living in Ecuador somewhere … so you get that type of situation that can happen, just like that. If you’re clever, you insure yourself against that sort of thing, and we do most of the time try and cover ourselves. But on the whole, artists are pretty tough people and they will usually perform under any circumstances.”

These days promoters insure the big risks: “We call this relatively new phenomenon ‘non appearance insurance’. When I got in the business in 1976 it didn’t exist. Mind you [back then] there wasn’t the need for it either, ’cos the big risks were about to come, and those were risks that we started taking on from about 1982 with the big shows and you just had to cover yourself.

“A group of insurers in London are the main group who look after non-appearance insurance. They farm it out, as insurers tend to do. The premiums are very high but you need that sort of security if you are betting 1.5 million dollars, which is money you don’t have. We can tell pretty early on if something that we bet on isn’t going to pay off and you’ve just got to ride with it. You get a sense of it fairly early on, but you don’t always get a sense of it before you’ve made the commitment: sometimes it’s just a little time after, and that’s the uncomfortable time.”

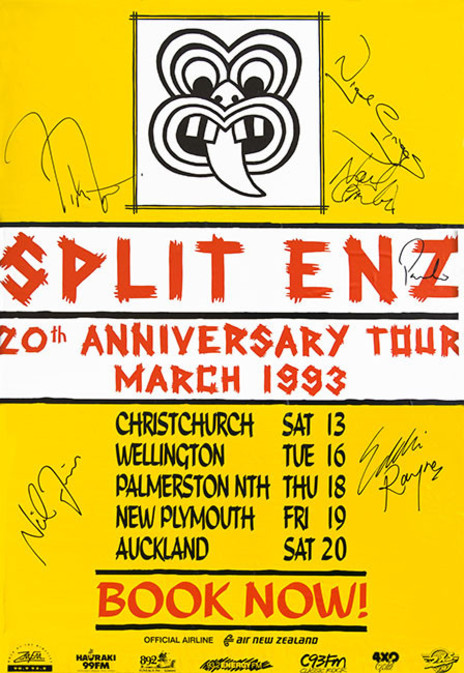

Split Enz 20th Anniversary NZ Tour, March 1993.

Are there any artists he has declined to work with? Magan is cautious with his response: “There’s a few I would rather not work with, but in saying that I’m having a problem thinking who they would be. There are a few who have just been difficult buggers to work with but I’ve been lucky. I’ve had a roster of people who I’m enormously proud off and had great experiences with. From our first tour with the great John Clarke [Fred Dagg] right thru – we’ve had a great run. There are a few artists like Iva Davies [Icehouse] who we had a ‘hesitant’ start with but ended up becoming great mates after two or three tours. We grew to like each other.”

What was the initial stumbling block with Iva? “I think at the time I probably thought he was a bit up himself, but he wasn’t up himself at all,” says Magan. “All he was doing was saying ‘I’ve got a professional level that I will move to and I won’t go beyond that in terms of compromise’. And sometimes we’d be asking him to compromise over little things, like the size of the stage for example or where the lighting is put up, what sort of vehicle they’re expected to travel around in, and if we expect them to compromise and they don’t want to, then you can get a conflict. The trick is rising above all that and giving them as much as what they want as you possibly can and building a relationship.”

There’s a saying that suggests one should never meet one’s idols. Did Magan ever get nervous or intimidated when he met an artist he likes? “Yeah … it’s a bit like a lot of artists will get nervous before they go on stage. It’s a very common situation, but we’re the same – particularly if you’re meeting an artist you’ve never met before.

“I met Bob Geldof ... and I was like a teenager.”

“I met Bob Geldof at Billy Connolly’s 60th birthday party in Scotland and I was like a teenager. I didn’t know what to say because he’s such a giant of a person. He might be a debatable entertainer but he’s a great person. I didn’t know what to do and I’ve been meeting celebrities for years. Michael Parkinson – I had the same experience with him at the same party actually. I was introduced to him and he was such a charming man and likeable person, I was lost for words … for a while.”

Magan has a very personable disposition, which may account for why he has had very few occasions in which he has had to deal with scurrilous artists or agents. Perhaps his only real no-show was with the late Chuck Berry. Magan related the story to Grant Smithies in 2017:

“Chuck Berry was a mean old bastard,” Magan said. In 1978, Magan booked Berry to play two dinner shows at 6pm and 9pm on the same night in Auckland cabaret Trillo’s as a double bill with fellow rock’n’roll legend, Bo Diddley.

“But Chuck shot through!” says Magan. “We had pre-paid him, because Berry always insisted on being paid before he played, in cash. So him and Bo Diddley did the first show then, in the interval, somebody came out from backstage and told me [Berry] had taken off in his car and was on his way to the airport.”

Magan was outraged. He jumped in his car and chased Berry. “I wasn’t gonna let him get away without a fight, and it nearly developed into one, too! I took off after him at high speed, and caught up with him at the airport just as he was checking in for the evening flight to Los Angeles.”

They exchanged “some very stern words”, says Magan, as he tried to prevent Berry from leaving the country without playing his second show.

“It was all pretty unpleasant, then he buggered off into the distance. He said to me ‘Stop me if you can’.”

Magan tried to get Berry arrested. “I called a policeman over and said, look, this man’s leaving the country against the terms of his contract, and he has my money in his pocket. Would you please stop him?

“But the policeman asked me to produce the contract and I didn’t have it on me, so Chuck just stood there, knowing there was nothing anyone could do. Once they called his flight, he just turned on his heel and took off through the departure gate. That’s the last I ever saw of the man.”

Angry and dejected, Magan had no option but to head back into the city and tell the audience to the second show what had happened. “We gave them half their money back and Bo Diddley played a longer show, bless him. He was a lovely man.”

Magan adds: “I have two very different views of Chuck Berry. On the one hand, there was this pretty nasty man ... on the other, a great songwriter and consummate performer whose stagecraft was magical on a good night. Chuck Berry was a magnificent performer.”

In one of our interviews, I asked Magan if there are some artists who are quite specific about their artist riders. It’s said that Meatloaf specifies no meat loaf in his rider. What were some of the more eccentric artist riders he has encountered?

Elton John’s rider: a sultan’s tent, ice statues, and French champagne

“The ones we always talk about are the outrageous ones, like when Elton John … he’s not like that now, but when he was a drinker and, I think it’s fair to say, a difficult person to deal with at that time. He had an outrageous rider. It cost us $50,000 to set up his backstage rider at Mt Smart Stadium way back. We had to put up a Sultan’s tent and it had to be specially lit, it had ice statues, special Champagne imported from France … oh my God, it was a nightmare. It was harder to fix up the rider than it was to arrange the show.”

There was a story that I’d heard from a local artist who supported BB King when he played New Zealand. Magan had arranged for elaborate platters of New Zealand delicacies, including Bluff oysters, but when BB’s tour manager and minders came through to inspect the arrangements, they told the promoters, “Mr King will not eat any of this food. He will want McDonalds.”

Magan confirms this, but he flips it with another story about how, when he toured The Stylistics – the soul group from Philadelphia – he “introduced the band to New Zealand fish and chips wrapped up in a newspaper and they thought it was amazing. Everywhere we went, they’d say ‘Hey where’s the fish and chips at man?’ so I’d be scurrying round back stage to find a fish shop that would be open at 10.30 at night after the show.”

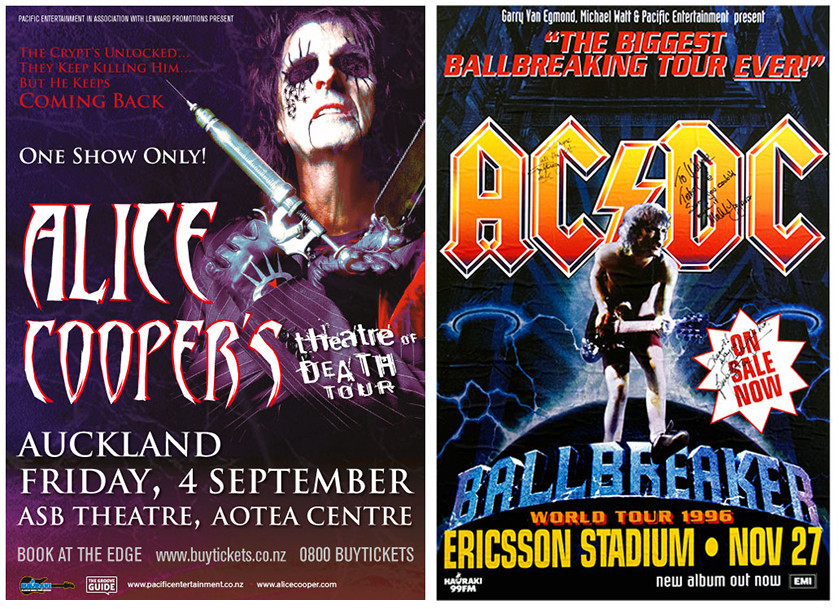

Alice Cooper 2009 NZ tour, AC/DC 1996 NZ tour, promoted by Ian Magan's Pacific Entertainment.

The easiest backstage rider was for Billy Connolly. “His backstage requirement was two bottles of Evian water and a pot of fresh tea. That was it. So we would tour New Zealand with a teapot, a hot-water jug and Evian water.”

Some artists, like Pavarotti, brought their own chef with them. “He was a big eater. He’d have a full-on four-course dinner after the show at the hotel. We were invited to that meal after the show and had our photos taken with him.”

Magan has a passion for music beyond the contemporary scene. He regarded Pavarotti as the royalty of opera, and he was an artist who required a totally different sort of production. “The main difference is that they are dealing with a huge orchestra which complicates staging as well as requiring a more specialised sound set up, because that orchestra has come from studios where they are used to properly controlled acoustics. Staging, lighting and video back drops are pretty much the same as rock’n’roll production.”

He says their company securing the Pavarotti tour was a gift: he was offered the show. Pavarotti’s agent had heard about his company and flew out from LA to meet and ask if he would produce and promote the Pavarotti show. Magan’s response was ‘You must be joking …’ They concluded “a good deal, a fair deal”.

Magan confesses he just had to pinch himself because he was a huge fan and had followed Pavarotti through his career. He had seen him performing in Sydney with Dame Joan Sutherland and was overawed by the beauty and power of the whole spectacle.

“We were very lucky to get him,” says Magan. “It’s just the magnificence of the voice, a great selection of music and a great conductor. He was quite eccentric but easy to deal with.”

Pavarotti was “quite eccentric but easy to deal with.”

Socially, Pavarotti was easy to keep happy. Magan had the privilege of taking Pavarotti to visit the Italian America’s Cup syndicate which was preparing for the America’s Cup down at the Auckland waterfront. “What a day that was!”

The Italian team had asked Magan if they could meet Pavarotti and the singer agreed, saying he would like to go down there and visit them, look at the boat and meet the Italian team.

Magan: “The team guys couldn’t believe it – they were nearly all crying because he’s a national hero and here he turns up at the boat depot, with rope and bits of canvas lying around the place. They had an hour with him. He didn’t sing, just talked to them and laughed and joked. It was a special meeting: they were so emotional, Pavarotti was emotional too. They were really nice people.”

Many of the artists he has worked with, Magan recalls with special affection:

AC/DC: “Long term favourites and still brilliant.”

BB King: “One of the finest guitarists ever.”

George Benson: “Again – one of the finest guitarists ever.”

Ray Charles: “All of the above. A gentleman and a fine artist until the day he died.”

Cher: “An aloof but talented person.”

Michael Jackson: “Brilliant, brilliant, brilliant.”

Eric Clapton: “A fine guitarist, a very nice person who will always be remembered for his huge hits.”

Alice Cooper: “He was a mystery to me because he was so outrageous with his costumes and stage sets.” (Magan didn’t get to play golf with Cooper, but loved his performance despite thinking that he wasn’t sure that he would.)

Roberta Flack: “She was just such a fine voice – one of the finest female voices I’ve ever heard – and totally dedicated to her craft.”

Norah Jones: “A great friend. We did two tours with Norah Jones that sold out everywhere. She’s such a fantastic performer, singing quite oddball songs that really got to audiences and nobody quite knew why they did, but they did.”

Kraftwerk: “Again oddball – I didn’t quite understand their music but loved the live performances.”

The Neville Brothers: “Aaron Neville in particular: a fine voice, a gentleman to work with and a great repertoire of songs.”

Bonnie Raitt: “Brilliant. A very pleasant person, very interested in New Zealand, loves the place and she gets really close to an audience and can get them in the palm of her hand.”

Paul Simon: “He’s more reserved as a person but delivers on stage … and that’s the main thing.”

Magan maintains that when assessing an artist’s value for the New Zealand market, “gut feel” is still the most important instinct to trust. In a 2007 interview he told me, “The minute it becomes a science, then its time to get out of the game. Gut feel is still important. Nothing is certain is still the number one rule, and you can never learn enough. It is not a finite business. If it were, it would be boring. I find that the spark of creativity is both a good thing and it can be, at times, a destructive thing, but it’s generally a good thing that makes people aware of themselves and life around them.

“There are only a few people who can supply that. As long as you’re working with that type of person it’s always going to be interesting. Something is going to be happening, but it’s not always easy: you just gotta hope that you make more good decisions than bad. It has to be a business [in which] you base a lot of trust on people. I suppose the only thing I can say for my 30-plus years is that I’m still there. I may or may not be a better person because of it, but I am still here.”