Early credits

He gets the credit for writing that Snapper-ish classic (at age 17) on Boodle Boodle Boodle. Gutteridge told Richard Langston in Garage No.6, “When we wrote ‘Point That Thing’ we didn't have any understanding at all, it just sounded good. It was the simplest thing ... and you could play it for a long time. You don't spend ages writing a song like that, it just comes.” Ironically, after developing that effortless, eternal bass line, he was booted from The Clean for not working hard enough at his bass playing.

Chucking aside the bass (which is conspicuously absent throughout the rest of Gutteridge's body of work) and picking up guitar, he joined the first post-Same phase of Martin Phillipps’ multi-banded The Chills, stuck around for two months, two gigs, and no recordings. “There wasn’t enough room for me to really explore stuff. It was too regimented. I’m not a particularly technical guitarist, but I like certain sounds. Certain rhythms. I’m interested in drone music as well as melody.” (Mess+Noise, April 15, 2013). The Bros. Kilgour invited him back for their early-mid-career sabbatical bag The Great Unwashed, and with them he appears on their Singles, and again on the Odditties 2 cassette.

Gutteridge began to develop his own material, away from the self-sewn Dunedin Sound which had already ossified into its particular style of jangly pop.

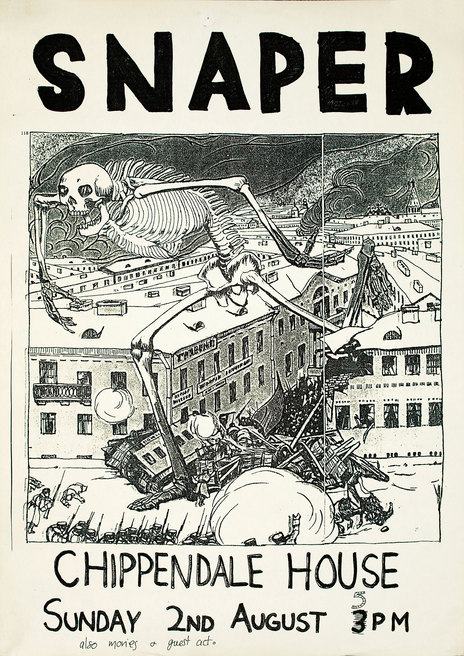

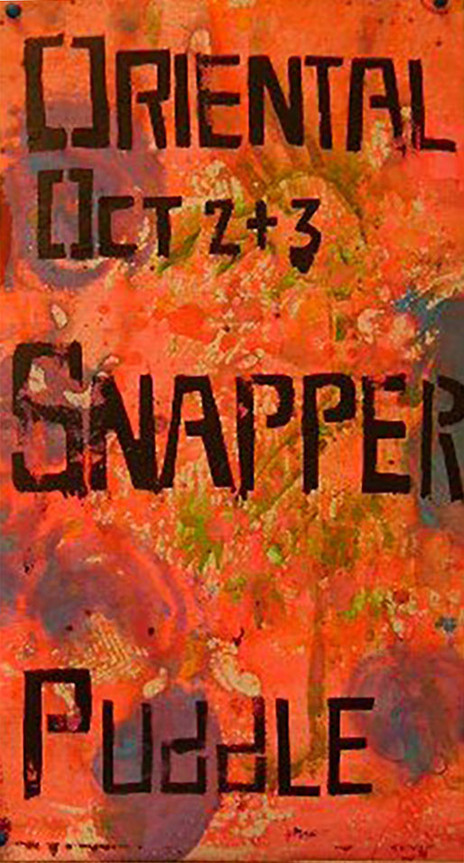

Not bad so far, eh. So what other legendary bands could this future bitey-fish cut his teeth in? Well, he played organ for damaged underground pop nabobs The Puddle, and for noted obscurities Alpaca Brothers. Then there are a couple of completely forgotten acts like the Craven A’s (featuring the fellow well-pedigreed Lesley Paris, Terry Moore and David Kilgour), The Cartilidge Family (with Shayne Carter) and the Bel-Curves/Belle Curves. “I've got bored staying with one band. Like living in Dunedin for a long time you just can't play with three people for a long time. There are other musicians and it's great to learn off other people.” (Garage No.6)

Finding the Snapper sound

Gutteridge began to develop his own material, away from the self-sewn Dunedin Sound which had already ossified into its particular style of jangly pop. He moved toward a stark new sound, unvarnished, dependent on drone and distortion. With a little drum machine, some keyboards and guitar, he followed Chris Knox's lead, and started recording on his own Fostex 4-track recorder.

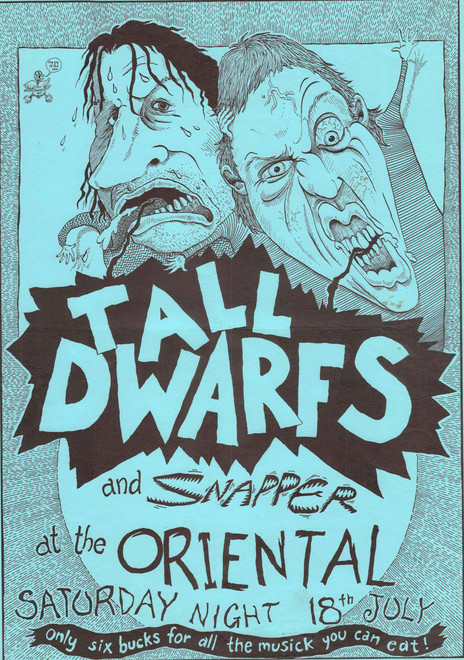

Some of these earlier experiments – which were later released by Xpressway on the 1989 cassette Pure – can get quite Knoxious, like 'Lonely': darker, less playful perhaps, yet still simple and direct. Or, despite its pitiless name, 'Dead Pony' with its bongo-beat and sweet riffing, and 'Pure No. 1', is quite feasibly a deconstructed and deleted track from Tall Dwarfs' Slugbucket. Elsewhere, 'Oil' and 'Bomb' both channel Voice of America-era Cabaret Voltaire, taking that album title literally with Gutteridge aping a snarky, smarmy American accent. In the thick of all this is the bent psych-folk mini-classic 'Planet Phrom', an effed-up flower-child's fever dream where our plucky adventurer and his alien wife "hold hands 'til our dying breath" beneath drug-dripping trees.

The lineup solidifies

Alan Haig and Gutteridge played together in the original line-up of The Chills in late 1980, but Haig stayed on for the best part of the next five years, with a stint in The Verlaines in about 1983. After hearing Gutteridge's tapes, they started playing together again in 1986, recording songs on the 4-track, Haig metronomically replicating the drum machine with his live, motorik rhythms.

Dominic Stones left Bird Nest Roys and Auckland, came down to Dunedin and proceeded to give it heaps. He spent some time in Bob Scott's Electric Blood, and would end up one 'D' among four in The 3Ds. On a drive with Gutteridge and Haig, Stones goes "gizza listen to those tapes", then says, “ahh, yep,” and with Stones along they became the Phroms.

Christine Voice came from a theatre background with the group Axolotl, and then started singing in Dunedin's The Elevators (which also featured The Chills' Martyn Bull). Gutteridge was someone she knew from the small Dunedin scene, but they met again – and hooked up – while he was touring with The Great Unwashed in 1984, and Voice joined Gutteridge (and the rest of the band) for the rest of the tour. Back in Dunedin, she joined the all-girl Delawares until a Delawares/Phroms gig, after which she and the Phroms were suddenly Snapper.

“We're into solid bedrock rhythms. There's not much room for fancy stuff. Ours is the rhythm that makes you tick. We find it and push it as hard as it will go.” – Peter Gutteridge

Like Stones, Voice was not a Dunedin native, and she found the close-knit Dunedin scene a bit of a (young) Old Boys Network. Almost everyone on the scene – including Gutteridge and Haig – had gone to school together, and were tight. With these two interlopers, and the other two refugees from the storied Dunedin Sound, Snapper was a new, dissident, aesthetic sect.

The name Snapper comes not directly from that mighty fish, nor from the naughty slang for lady-parts (that award goes to BLERTA), but from the name of Gutteridge’s kitten, killed by a car. She gave name to the cage where all those soft 'n' fluffy symbolic butterflies went to be broken upon the unstoppable greasy wheel of Snapper's malignant system.

Rhythm and distortion

Snapper's substructure is rhythm, Gutteridge's private, psychic pulse. It was basically there in The Great Unwashed, on tracks like 'Can't Find Water' from Singles, but fully took form when he began to work on his own material, and ultimately with Snapper. Gutteridge told RipItUp: “We're into solid bedrock rhythms. There's not much room for fancy stuff. Ours is the rhythm that makes you tick. We find it and push it as hard as it will go.”

The rhythm comes first, and on top of that, distortion. Gutteridge became interested in drone and distortion while still in high school, thanks to Dunedin's omnipresent Scots-heritage scourge, the bagpipe. The Velvet Underground is usually name-checked as the major, unwavering influence on Dunedin music, and while all seem inspired by the punk attitude of Lou and Co., a fair number focus more on the softer side of their second two albums, a sort of black paisley pop. Though Snapper can do mellow (ie. 'Dead Pictures', 'Gentle Hour', 'Snapper and the Ocean'), they're much more hooked on the everybody-keeps-turning-up-their-amps style of White Light/White Heat's 'Sister Ray'.

There is power in loudness, there is beauty in distortion. Voice, Stones and Gutteridge all had the same Alron brand distortion unit, which they applied to practically every layer of sound. “On some of my tapes I even apply it on drums. You can make a note last and sort of hum behind you ... instead of a chord just going WHAM and dying off, you can play with it and make it feed through. It becomes sort of like a tentacle, something long and drawn out.” (Bill Meyer, Option, 1991).

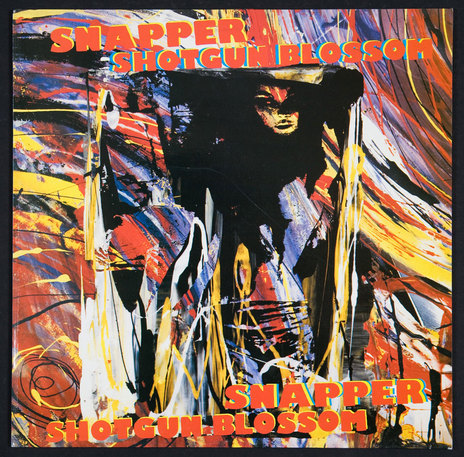

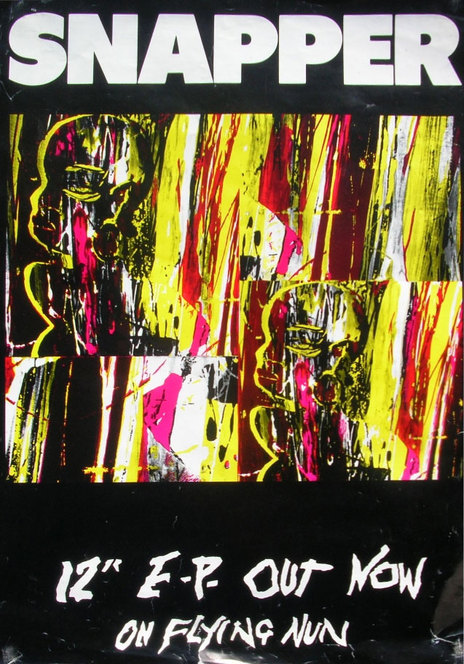

The final act in the manufacture of a Snapper sandwich is layering, like the great swathes of caustic colour in Voice's cover painting for their 1988 self-titled EP. The overlapping drones in 'Death & Weirdness in the Surfing Zone' from that EP create a sense of moving in geologic time: The strata of mantra-like lyrics, the ostinato organ textures, the timelessness shaken off only through an occasional lift with a chorus riff. It's difficult to take it all in in one listen, for as simply structured as these songs seem, there's a hell of a lot of interplay between the tiers of rhythm and timbre.

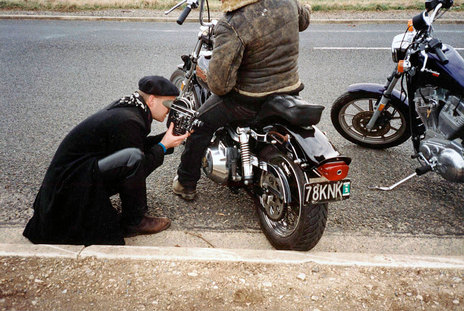

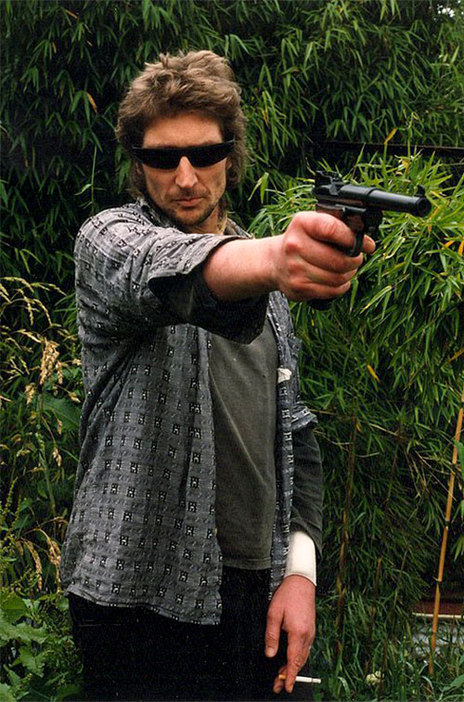

Opening track 'Buddy' is still Snapper's biggest hit, and the soundtrack to their sole video. Directed by the Axemen's Stuart Page, the video is full-fledged Snappervision: Skulls, strobes, and sunglasses, and black-clad Gutteridge giving you the fingers while speeding down the highway on the back of a big black bike.

Bruce Russell released the compilation cassette Xpressway Pile=Up on his Xpressway label in 1990, which included two demo tracks by Snapper: 'Emmanuel', recorded in 1989 at Studio 13, and 'Death and Weirdness in the Surfing Zone', recorded on a Portastudio at Snapper's practice space in 1987. Edinburgh-based Avalanche Records put it out on vinyl, then released a one-sided 7-inch Snapper single, and next their 1990 album Shotgun Blossom.

Even amongst all the death-squeal feedback, chundering distortion and merciless lyrics, it's not all dark. You can dance to this record, or at least nod along with a mad grin.

In full bloom

Scabrous distortion cracks off the pop-song-short and pop-song-cute opener 'Pop Your Top' on first full-length release Shotgun Blossom, before fading into feedback-drenched instrumental 'Can' – a none-too-subtle nod to the krautrock pioneers. Then Voice's eponymous talent gets to shimmer on 'Eyes That Shine' and 'Dark Sensation', and by mid-record the Snaps are at their most sweet-tempered, with undistorted guitars and upfront vocal harmonies on the dulcet 'Dead Pictures' and 'Snapper and the Ocean'.

'What Are You Thinking' is model Snapper: A heavy nodder built around a two-chord drone and a lateral 4/4 amble, awash in whistling digital reverb. Likewise, 'Hot Sun' is model Stereolab (London-based electro-poppers, who originally featured another ex-Chill, Martin Kean, on bass), those unashamed appropriators who used Snapper (and Neu! and exotica, et al.) as a major framework for their sound.

That little beach-boogie is swiftly squished by the mountainous 'I Don't Know', brandishing its big fat throbbing organ and rusty-hinge whinging guitar, and tentatively negative chant, "I don't know if the world's gonna last that long".

Even amongst all the death-squeal feedback, chundering distortion and merciless lyrics, it's not all dark. You can dance to this record, or at least nod along with a mad grin. Shotgun Blossom made No.12 on the NME independent charts in 1991.

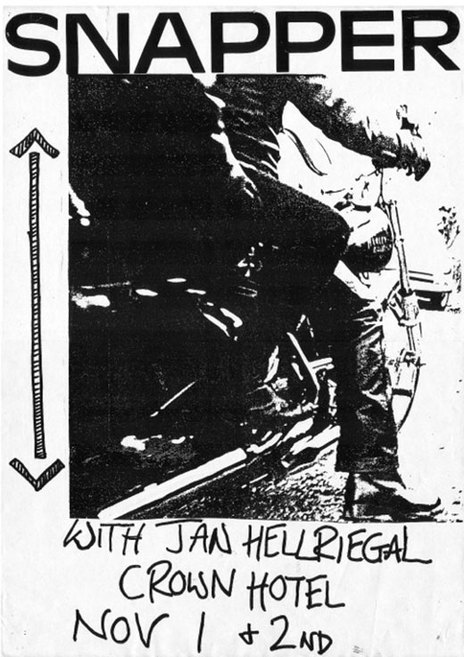

Stones and Haig left the band by 1992, to be replaced by Gutteridge's old school friend (there's that impenetrable Dunedin scene again) and ex-Great Unwashed-mate David Kilgour on guitar, and ex-Toy Love/The Enemy drummer Mike Dooley. The new line-up recorded the Flying Nun single (which had been provisionally titled ‘Holesome’) 'Vader' b/w 'Gentle Hour'. Ex-Chills-mate Martin Phillipps joined Snapper for a gig at the Crown that year, two weeks after The Chills abandoned their American tour.

During the next four years, Snapper only released one track, 'Sand' – recorded at Fish Street Studios in 1994 – on the Kiwi Rock 1996 compilation. The foggy sizzle of this demo-ish piece is a boiled down, soporific rework of Pure's earlier version, which was a zippy little ditty with a bemusing, Polynesian-C&W twang.

Then there was (mostly) one

Snapper was now just Gutteridge; he played everything except drums and guest vocals on the second album. From the first word ("motherf*cker") of the first song 'Tomcat', 1996's A.D.M. promises a much darker trip. “A.D.M. was the darkest thing I've done,” said Gutteridge in Mess+Noise.

Gutteridge hates the term "psychedelic", and Snapper is never mind-expanding, it's mind-derailing: A woozy, vertiginous plunge rather than a floaty dream. After that initial oath and amongst the muttering, snarled incantations of "razorblades" and "eats his own kind" show Snapper were finally, utterly, sinister. Gutteridge's slithery, whispery vocals on 'Hotchkiss' are a sore-throat rasp, all grizzled sickness, backed by a tremolo guitar sound that recalls the 13th Floor Elevators' "electric jug".

The opening five seconds of 'Demon' demonstrate the Snapper structure: Each layer of sound starts separately, like runners staggered on a circular track. The introduction to title track 'A.D.M.' (named for T4 Atomic Demolition Munitions, modified versions of nuclear artillery shells), with its stereo-separated Tesla-coil crackles-and-pops, is the 'Snapper' appellation grown onomatopoeic. 'Killzone 44' is Snapper at their most Suicide-ish – all deadpan growls in Gutteridge's most dangerous Alan Vega swagger. By now, all the Americanisms of Gutteridge's early style have matured/degenerated into an American Gothic, Mickey-and-Mallory, white-trash-terrorist saga, as in the vicious, doubled vocal ejaculations on the sadistic 'Stalker', which literally seem to sneak up and scare the listener into looking over their shoulder. Album closer (and the closest thing to a possible single) 'Used to Know Her Name' invokes Faust IV's 'Krautrock', with the imagery of Kraftwerk's 'The Model' reflected in a black mirror. A.D.M. is undeniably Gutteridge at his most nominatively deterministic: Gutteridge = guttural, guts, the gutter.

Post-ADM

After A.D.M., Gutteridge left Snapper to rest. He joined HDU in 1997 to record 'Point That Thing Somewhere Else' for Flying Nun’s God Save the Clean tribute album, and performed it at the album release party at The Powerstation in Auckland. He played in differing versions of Snapper but rarely, including the Dunedin Sound Showcase at the Otago Festival of the Arts in 2000, and not again until a gig at Sammy's in Dunedin in 2005. He continued to write music, including a legendary body of piano works, yet to be released.

One of these heavily reverbed, phased and looped piano experiments showed up in a cover of 'Don't Catch Fire' on the Chris Knox tribute album/fundraiser, Stroke. In mid-2012, Gutteridge began playing gigs around Dunedin more frequently, and by early 2013 was playing around New Zealand in various incarnations of Snapper. For Record Store Day 2013, Flying Nun and Captured Tracks re-released the self-titled Snapper EP on vinyl, and a remastered version of Shotgun Blossom is planned.

In August 2014, Gutteridge travelled to New York for his overseas debut at Palisades in Brooklyn, performing songs from Pure with a local backing band. Returning to New Zealand, he arrived at Auckland airport in extremely ill health, and passed away on 14 September. Shocked by the sudden loss of this flawed but seemingly bulletproof legend, local artists and press wrote dozens of tributes, and Gutteridge was eulogised internationally by Rolling Stone, Billboard, and The Guardian.