Dubhead (Patrick Waller) at the 95bFM studio.

Patrick Waller was born in Cheltenham, a garden town in Southwest England, in 1964. Four years later, his family emigrated to New Zealand and settled south of Auckland in Maraetai Beach. “We arrived in July, a man landed on the Moon, I had my fifth birthday and went to primary school,” he recalls.

Music was a constant in his family life, with the household listening to 1960s British pop, dixieland jazz, musical soundtracks, and classical music on Sundays while cleaning the house. “My parents were both into music and had a really good record collection.”

Waller was fascinated by vinyl records and record players from a young age. After he started putting records on the turntable while his parents watched the news or tried to sleep, they gave him his own portable turntable and a stack of 7” singles. “I was probably about eight,” he laughed. “They were like, okay, son, that’s your stereo. These are your records. Now stop messing with ours. I think that’s when I fell in love with 45s, 7”s, little cute dinky records that only played one song.”

In that moment, Waller’s parents set him on the pathway to becoming a DJ.

Choirs and classical music

By the time he was 11, Waller was skateboarding and saving pocket money from his chores to buy records from English orchestral pop and glam-rock groups such as Electric Light Orchestra and T Rex. He enjoyed choral music and would accompany his mother to practices and performances with the South Auckland Choral Society. One year, they participated in a massed choir performance of Handel’s ‘Messiah’.

“It blew my mind to be part of something so big sounding,” Waller said. “I’d never seen a live rock band at that point. I had never seen a reggae sound system. I’d never seen anything loud, but to be in the choir of hundreds of people, all singing the same piece of music with an orchestra and a pipe organ, was like, wow, this is powerful.”

When he was 12, his parents sent him to boarding school at King’s College in Auckland. His father, a bearded, thick-jumper-wearing beatnik who was a founding member of The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament and ran a jazz wine bar in Cheltenham, had reservations about his son spending time with the children of rich people. On the other hand, Mum was convinced King’s College would give Waller a great education.

As it turned out, King’s College was a good school for music. “They had a fantastic musical director there, Dr Phillip Bird,” Waller said. “He was from Australia and had a lot of enthusiasm for music education.” At King’s College, he learned music theory and how to read music. Under Bird’s guidance, he followed in his grandfather’s footsteps and became a skilled classical cellist, eventually inheriting his antique French cello after he passed his Trinity College music examinations.

“So, I turned 15, and I was in the chamber orchestra, a small orchestra of 12 players,” Waller remembered. “I was also in the full-school orchestra and singing in the King’s College chapel choir. Phillip had recording equipment and decided that we should record our performances and make records.”

Discovering punk rock

At the same time, Patrick’s worldview was transformed by the arrival of punk rock in New Zealand. “Suddenly, I realised the world was grossly unfair,” he says. “I remember specifically hearing The Sex Pistols and going, what the fuck is that? That sounds great.”

From there, it was a quick jump to listening to Barry Jenkin aka Dr Rock’s late-night radio shows on a palm-sized transistor radio. “The music he played was just a revelation,” Waller enthuses. “Swell Maps, The Mekons, and The Fall were his favourites. Just amazing stuff, The Birthday Party, Young Marble Giants, all the Rough Trade acts.”

The music Barry Jenkin played on radio “was just a revelation,” says Waller

Things went to the next level when his parents took him to Open Day at the University of Auckland. “At the time, I was interested in architecture, so we went down to the School of Architecture to look,” he says. As they were crossing the quad, they ran into a local electric blues band performing on a stage. Waller was transfixed, having never seen a band play live through a PA before. “I thought, this is what I want to do,” he remembers. “I want to be on stage with the band. It was great.”

In 1980, when he was in Year 12 (then sixth form), the King’s College chamber orchestra won the National Secondary Schools Music competition. As a result, they were invited to travel to Melbourne to perform at an international youth music festival. “We played in the Victoria Art Museum and the Melbourne Cathedral. Really big venues with big audiences.”

That year, Bird helped them make a private-press vinyl LP of recordings of their performances. “I was very interested in the recording equipment, how he actually physically recorded it, and how it got turned into a record,” Waller says. “I got so involved that I ended up designing the record cover.”

Entering adulthood

In 1981, Waller finished high school, informed his parents he needed a gap year before university, got a job as a record store clerk at Two Fifty-Six Records on Queen Street, and went flatting. Through his flatmate Karen, he fell into the same circles as Rip It Up writer Mark Phillips and musician and DJ Peter Urlich. Fascinated by the rise of jazz-dance, modern soul, and club music in the UK, Phillips and Urlich opened a pioneering Auckland nightclub called A Certain Bar on Wellesley Street in Auckland’s CBD where they DJed along with friends such as Simon Grigg. After Waller spent some time working the door there, they started letting him take over from them for a spell on the turntables.

“The music they were playing was absolutely curated,” says Waller. “It was a really weird mixture, but it was for the people, which was a really diverse crowd of people: new romantics, punks, LGBT, a real mixture of weirdos and freaks. The music was Visage, Ultravox, ABC, and Haircut 100. So all the sort of new romantic stuff, but also mixed in with some older soul. You know, they’d play James Brown, Grandmaster Flash. There was rap, electro, and disco. Mark and Peter knew what they wanted to do: play music that these people would like.”

As well as DJing with Mark, Peter and Simon at A Certain Bar, Waller picked up his own residency “The Dancefloor” just down the road at the rock’n’roll club King Creoles. At the time, the bar’s resident DJ was Russell Crowe, then better known as Rus le Roq; Tom Sharplin and The Cadillacs would play covers on Friday and Saturday nights. Waller looked after Wednesday and Sunday nights, where he would DJ a mixture of the bar’s in-house disco and funk record library and his own fast-growing collection. “I’d play ‘The Message’ by Grandmaster Flash and The Furious Five after ‘Megatron Man’ by Patrick Cowley,” he recalls.

Later on, when Mark and Peter opened their second nightclub, Quays, they had Patrick come down and play a solo cello performance at the opening. “When I talk about my early years in music in Auckland, a big part of it was older men encouraging me,” Waller reflects. “I was a young guy who was full of enthusiasm and keen to do things. There were a bunch of older guys who set a good example, gave me opportunities, and, most importantly, gave me confidence.”

Having been interested in ska, rocksteady, and reggae since his high school years, Patrick was floored by classic dub albums such as LKJ In Dub, UB40 Present Arms In Dub, and Burning Spear’s Garvey’s Ghost. After he read a feature story on UK dub producer Mad Professor titled “Crazy Dubhead” in the New Musical Express (NME), he knew what his DJ name should be. “I was all about the dub,” he says. “Okay, I’ll be DJ Dubhead.”

Silent Decree

While Waller was beginning his DJ career as Dubhead, he was also finding his way into the world of live music as the lead singer in a gothic punk band called Silent Decree, with three young guys around his age from Howick. “We sounded like Bauhaus’s vocals on top of Siouxsie and the Banshees’ music,” he says.

Harrowingly, the first time they performed – a show with Flak and a couple of other bands at St Benedict’s Hall – an audience member was stabbed and died. For Waller and his bandmates, it was a confronting introduction. “This was the early eighties, and it was the time of skinheads,” Waller remembers. “There was a lot of actual street violence at the time.”

Harrowingly, the first time Silent Decree performed, an audience member was stabbed and died.

From there, Silent Decree played at Spam, which later became The Venue (an all-ages music venue then run by Russell Crowe), made a late-night performance in Grafton Cemetery, and rocked the popular Mainstreet venue demolition party. For Waller, however, their golden moment was when they opened for The Gordons at PR Bar. Several years later, when The Gordons had morphed into Bailterspace, Waller played alongside them again, but this time as DJ Dubhead. “I got to play industrial and dub records at the same show as them and Nemesis Dub Systems,” he says. “I don’t think anyone else has gotten to support The Gordons (Bailterspace) in a band and as a DJ.”

Alongside playing live around Auckland, Silent Decree also made studio recordings. Thanks to some financial support from his mother, Waller had completed a short audio engineering course at Harlequin Studios in Auckland. “DD Smash and The Gordons had recorded there, so I knew it was a great studio,” he said. During the course, Patrick learned microphone placement, and how tape-recording machines, equalisation and mixing desks work. “We learned the whole science of it,” Waller enthuses.

All of this was invaluable when Silent Decree decided to track a four-song EP called In Loving Memory (1983) at Progressive Studios on Anzac Avenue with the engineer Terry King. “It was self-released, but we got distribution through my friend Paul Luker, who ran the Industrial Tapes cassette label,” Waller remembers. “We gave him copies, and he got them into all the stores.”

A reggae song

That same year, Waller decided he wanted to record a reggae song. He approached Jon Cooper, an audio engineer who worked at Last Laugh Studios on Vulcan Lane, who agreed to work with him after hours as an experiment. Waller selected an obscure Jamaican reggae song called ‘Rasta No Born Yah’ by Sang Hugh for the recording. As he put it, “I recorded the drums and the bass guitar live, the rhythm guitar, keyboards, vocals and backing vocals. I did everything myself.”

At the time, Waller was working as a glassie at Mark Philips and Peter Urlich’s third nightclub, Zanzibar. Once he had a finished copy of ‘Rasta No Born Yah’ on tape, he took it to work with him. When the club was emptying out, they let him play his reggae song through their sound system. “It sounded so good on their PA,” says Waller. “It was proper, a real reggae song.” Recording his own version of ‘Rasta No Born Yah’ was the precursor to another important studio moment in Waller’s life, but we’ll come back to that later.

The Kiwi Animal

After playing together for several years, Silent Decree broke up when their guitarist departed for his OE in the UK. Not long after, Waller was approached by Brent Hayward and Julie Cooper, who were performing acoustic anarcho-folk music together as The Kiwi Animal. “They were doing recording sessions for their first album, Music Media,” says Waller. They thought it would be nice to include some cello on some tracks.” Once they’d reviewed the recordings, Brent and Julie asked Waller if he’d like to join The Kiwi Animal. “I said, ‘Yeah, I’d love to’. We were quite different to everything else happening at the time. We’d play in art galleries and small theatres. Beautiful spaces with beautiful acoustics. We even played at the old Jewish synagogue up on Princes Street.”

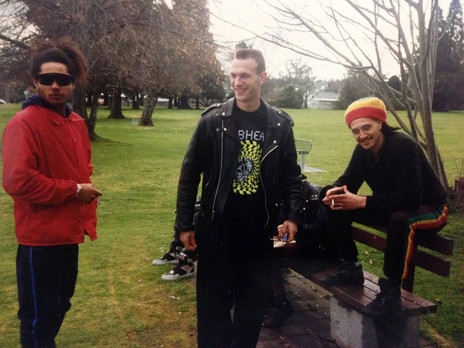

The Kiwi Animal: Brent Hayward, Julie Cooper, Patrick Waller. - Dubhead Collection

After releasing their second album, Mercy, in 1985, The Kiwi Animal broke up and went their separate ways. In the decades since, in testament to their originality and depth, both of their albums have been reissued multiple times in Europe and America. “To this day, those recordings are unlike anything,” says Waller. “Can you find another acoustic three-piece doing this sort of music?”

Patrick Waller, Brent Hayward and Julie Cooper recording in the Knox Presbyterian Church, Parnell. - Dubhead Collection

Before The Kiwi Animal wrapped up, however, the trio was approached about performing at a cutting-edge arts festival called ANZART (Australian and New Zealand Artists). For ANZART, they put together a sound piece called Woodcut. In Waller’s words, “Julie played a wooden drum, Brent chopped firewood with an axe, and I skillsawed pieces of 4x2 timber. So we were sort of somewhere between performance art and experimental music.”

Outnumbered By Sheep, a 1986 BiFiM release of mostly Auckland-based artists released on the label Campus Radio BFM and distributed by Flying Nun. Cover drawing by David Mitchell, coloured by Chris Knox.

Not long after, they were approached by Campus Radio (now 95bFM) and Flying Nun about contributing a track to a compilation LP called Outnumbered By Sheep. Thinking back to seeing the Japanese musician, visual artist, and sound explorer Akio Suzuki perform a very avant-garde piece at ANZART, they decided to pay tribute to his spirit by submitting a mixture of crystal glass water noises, the sound of ripping paper and wartime field recordings called ‘Dragons In Eden’. To their surprise, Campus Radio and Flying Nun not only agreed to include it on Outnumbered By Sheep, but they actually used it to open the B-side of the record. “It’s completely off the wall, but they put it on there. That was kind of our way of signing out.”

Phantom Forth, Surgical Brain Implant, Drugs, and A Physical Fling

While he was playing with The Kiwi Animal, Waller was briefly living on a couch, with Paul Luker from Industrial Tapes and his flatmates. In 1981, Luker formed the drum machine post-punk group Phantom Forth with his sister Debbie Luker and their friend Lorraine Steele, later recording the minimal wave classic The EEPP for Flying Nun. In exchange for staying with them, Luker asked Waller if he could play percussion with them at some shows. “They were a very beautiful minimal thing,” Waller said. “It kind of reminded me of Young Marble Giants.” Fittingly, Waller’s percussion gave Phantom Forth’s bedroom sound a big-room feel.

Several years after his time in the The Kiwi Animal, Waller got closer with musicians Roger Allen and Lindsay McKay, who lived off Karangahape Road at The Red House, a crucial hub for Auckland’s alternative music and arts subculture of the day. In the eighties, they played in the psychedelic group ?Fog, which later evolved into Surgical Brain Implant before changing again into Sperm Bank Five. During their Surgical Brain Implant era, Waller joined the band on bass guitar. “It was fun playing with them, and it was sort of different,” he says. “We were playing songs that sounded like punk rock spy movie themes.”

in the late 80s, Waller participated in two more bands: There Was Drugs, and A Physical Fling

Before the decade ended, Waller participated in two more band projects. There was Drugs, the trio he shared with the electric guitarist Graham Sinclair (formerly of 52) and Pip Anderton, and A Physical Fling, a duo project with Kelly Rogers (The Newmatics, Miltown Stowaways).

“I played acoustic guitar or cello, Pip played violin, and Graham played his guitar through a Korg MS-20 synthesiser, so it was synth guitar,” Waller remembered. ‘Drugs was very avant-garde. A bit like The Kiwi Animal but more like Frank Zappa. No drums, no rhythms, just electric-synth guitar with acoustic instruments. A New Zealand band called Drugs, you’ve got to put that in the story, don’t you?”

On the other hand, A Physical Fling was a performance art project with Rogers on saxophone and Waller on cello, along with some produced beats and live percussion. Although they formed to make a specific commissioned performance, they also made some recordings. “I don’t know what happened to those recordings,” says Waller. “They were never released.”

Screen-printing band T-Shirts

In 1989, Waller started working for the textile designer and musician Mike Brookfield (Fetus Productions). “Mike had a label called VIRUS Clothing,” he said. “He had this idea to screen-print industrial designs onto metres and metres of fabric and then make clothes out of them.”

Having previously worked in the printing industry as a labourer on four-colour presses, a plate maker, a guillotine operator, and a process camera operator, Waller had a solid understanding of screen-printing and access to the VIRUS clothing workshop on Karangahape Road. During his downtime, he started printing his own T-shirts under the brand Optricks Print. “Like Patrick, but optical prints,” he explained.

Planet Magazine takes the NRG dance party from Auckland to Wellington by bus, 1990: Palm Tree, Dubhead & Digi Gad stretch their legs in Taupo. - Photo Gene Jouval

As part of this, he printed up a run of DJ Dubhead T-shirts and was over the moon when Eddie Chambers from NRA wore one on the cover of Rip It Up. Not long after, Flying Nun asked if he could print them some Fuzzy F Man T-shirts (the Flying Nun logo). Later, he printed T-shirts for Dimmer, S.P.U.D., Headless Chickens, The 3Ds, and The Jean-Paul Sartre Experience. “Even though none of the bands I was in released albums with Flying Nun, I still became part of the Flying Nun empire, but as a screen printer,” Waller said. “I did it for two or three years. I’m not even sure why I stopped.”

--

--