At the turn of the century Don McGlashan’s dream was turning into dust as his group The Mutton Birds reluctantly gave up its ambitions to reap international success. He had given it his best shot: in 1996 the group had moved to England, where they had been signed to Virgin Records, been hyped up in all the right magazines and media, and toured relentlessly. And even after Virgin gave up on them, they kept plugging away for several years. But all to only so much avail.

The Mutton Birds: David Long, Ross Burge, Alan Gregg, Don McGlashan.

It was clearly a bittersweet experience, and when McGlashan returned to Auckland with his wife and young children in 2000, his confidence had taken a massive blow. It was time to buckle down and bring home the bacon. Thankfully, there was film soundtrack work available. Over the years McGlashan has composed music for television shows and films including 1990's An Angel At My Table, No. 2 and Dean Spanley. In 2019 he contributed songs for an animated series, Kiri & Lou, made by his former Front Lawn partner, Harry Sinclair.

“Soundtrack work has kept me alive all these years by supplementing what I earn from gigs and records,” he says. “I couldn’t have survived, or kept the family going without it. I’m a songwriter and performer first, but I’m proud of the soundtrack work I’ve done. It’s given me some great experiences, like writing for and conducting the NZSO. That was a great thrill.

“It’s been valuable to my songwriting. There’s a sense of ‘I can do this!’ when I’ve just finished a tough cue that moves the story along and has some musical integrity, and it’s quite often given me the confidence to pick up a tough song I’ve been working on and go at it with renewed energy.

“There’ve been times I’ve struggled a bit, thinking, if I spend time on other stuff, I won’t write all the songs that are in me. Or even if I do, they won’t be as good as I want them to be. But those sorts of doubts are a pretty constant companion anyway, and I’m learning to keep them down to a dull roar. Many composers in bigger countries would kill to be able to point to a career spanning 15 or so feature films and a bunch of TV series.”

Then there’s the hit song that is perhaps the hardest in McGlashan’s catalogue to reconcile with his usual writing style: ‘Bathe In The River’, a fully-fledged gospel song featured in Toa Fraser’s 2005 film, No. 2.

“That was kind of magical,” says Don. “I was working on the score, and the time came to replace a Mariah Carey song that Toa initially wanted with something he could actually afford. Toa reckoned he needed it before the actual shoot, so I wrote it well before the rest of the score, and all I had to go on for context was the written script. That and the brief Toa gave me fitted with sketches I'd been working on for a few years – of some kind of secular gospel song about wanting to dive into life, not just tiptoe around the edges. So once I started, it flowed pretty easily, and I think it only took me a few days, which is rare for me. I can work on a song for months.

Don McGlashan and Hollie Smith, Womad. - Michael Flynn

“I recorded at the Lab and Platform studios in Auckland, and at Plan 9 in Wellington, with Bella Kalolo singing lead, the Jubilation choir, and a big band. Stephen Small was on piano, Sean Donnelly on bass, Will Scott on drums, David Long on guitar, Jason Smith on Hammond, and a brass section of me on euphonium, and Toby Laing and Steve Roach on trumpets. Several months later, when I was nearly finishing the music for the film, Toa heard Hollie singing with Trinity Roots, and he suggested we try her on the lead vocal. I wasn’t that keen, as I thought Bella had done a great job with the song, but as soon as Hollie sang the first phrase I knew we had something extraordinary.”

As soon as a clip promoting the film using ‘Bathe In The River’ was shown on television, people went crazy for the song. “The record took off in a way I’ve never seen happen before, even though we didn’t initially release it as a single. People were buying the soundtrack album to get that song.” The song reached No.2 in the New Zealand charts.

Hollie Smith and Don McGlashan with band and choir, performing Bathe In The River at the 2006 New Zealand Music Awards.

This was exactly the morale boost that McGlashan needed after the nasty business that had sullied his memories of The Mutton Birds experience. And as with so many New Zealand acts trying their best to navigate their way to success on foreign shores, it was the business of business that put a sour taste in his mouth, not the music.

The Mutton Birds was a necessary step in McGlashan’s realisation that what he needed to do was write songs and sing them.

Looked at from the long view, The Mutton Birds was a necessary step in McGlashan’s realisation that what he needed to do was write songs and sing them, and a rock group seemed the most sensible way of achieving this. The lineup coalesced around guitarist David Long, who had played in The Six Volts, a Wellington jazz band that contributed to Songs From The Front Lawn, and former Dribbling Darts Of Love members Ross Burge (drums) and Alan Gregg (bass).

The group’s self-titled 1992 debut album was an instant hit, containing as it did their re-rub of The Fourmyula’s classic, ‘Nature’, and McGlashan’s ‘Dominion Road’. ‘Nature’ sailed to No.4 on the local charts, refreshing the close-to-forgotten hit song from 1970 in the public eye; in 2001 it was voted by APRA NZ members as the greatest local song from the past 75 years. ‘Dominion Road’ only made it to No.31 on the charts but insinuated its way into the Kiwi consciousness to such a degree that it became a genuine anthem. The song’s astute observations about one of Auckland’s dreariest long stretches of asphalt were by no means positive, but it also came with a deliriously catchy tune.

Here, at last, was McGlashan’s chance to show what he had to offer in a band context shorn of theatricality or art pretensions.

“I’ve never wanted to front anything, but in The Mutton Birds I realised I had to do it,” he says. And front he did. Having exhausted the limited potential of their homeland and now signed to Virgin Records, in 1996 the group relocated to the UK. Within a year, David Long had left the band and was replaced by former Dance Exponents guitarist Chris Sheehan.

These were heady times for the band, with the usual promise of big things waiting for them if they played the game right. But how to play the game when you don’t understand the atrophied way they do things in the Mother Country?

“In New Zealand your collaborations are formed by friendships and people who ring you up and say, ‘I saw that thing you did, it’s fucking brilliant, can we work together?’ and over there it was much more about where on the ladder you fitted. And early on we were trying to find someone to do a video clip for ‘She’s Been Talking’, which was going to be one of the singles from Envy Of Angels, and somehow I’d met the woman who did ‘Red Right Hand’ for Nick Cave and I just loved that stuff and thought something dark and black and white would be cool. So, she did a pitch and we got all these mixed messages back from the Virgin people, and they started off saying, ‘Well, research has proved that black and white clips sell 13 percent less than colour clips, so we’re not going to do that’, and all this stuff that didn’t make much sense came back. And then finally somebody took me aside and came clean and said, ‘You shouldn’t be telling us who’s going to do the clip. Don’t go out and make your own contacts because that’s not your job.

“We got those sorts of conversations all the time. They were very sweet at Virgin but there were also all these protocols, English protocols. Like we thought that it was good to go into the record company every so often to say ‘Hi, keep up the good work, good onya’, and after a while they said, ‘Don’t come in as often, because when you come in we have to get all ready and we have to have a welcoming party and we have to be all over you, and it takes us away from the work that we’re doing.’”

Don McGlashan, The Mutton Birds.

It wasn’t all bad, however. “There were aspects of it that were great, like being able to go on MTV and then get straight in a van and go to Belgium … the early stages were amazing because Steve Hedges was co-managing us and he’d just come off a stint managing Peter Gabriel and he was Oasis’s agent, and he got us onto all these bills, all these summer festivals, so we did Glastonbury and all these fantastic festivals around Europe and lots of gigs all around the UK, and there was just that sense that we were really working at the top of our game.

But there was attrition as well. “As David Long said when he left the band, ‘No matter how hard you try, no matter how many sleepless nights you spend driving from one gig to another, there’ll be a young band that’s prepared to do one more hour. And what we’re doing is inhuman.’ And he was right.

“The industry is set up to chew you up and spit you out.”

“The industry is set up to chew you up and spit you out. And it contains all of these contradictions. On the one hand you’re making something that will last because songs are ways of remembering important things, and traditionally, historically, before the music industry, we wrote songs to hold onto things. So there’s that longevity and sense of making something important, and then there’s this disposable aspect of the industry, where it just wants a new 15-year-old. And the two things co-exist. You’ve got both of those realities and all the evils that go with it.”

Ironically, it was the last leg of the group’s stint in England that was the most enjoyable for Don, because by then they’d been dropped by Virgin, and could just enjoy the ride.

“When we were making it up ourselves and not being looked after by the record company it was better because I guess we realised that there were other roads. Our manager said, ‘We haven’t got Virgin anymore, we haven’t got the major music press particularly, Q and Mojo magazines love us but we don’t have much other coverage, so let’s just go out and get the audience one by one, tour and tour and tour’, and that was pretty cool. We could have carried on doing that if we hadn’t decided to come back, but my kids were at an age where we could relocate them and my mum got really sick, so it was a good time to come back to New Zealand.”

The Mutton Birds.

So, what is The Mutton Birds’ legacy? Between 1992 and 1999 they managed four studio albums, mounted a four-year assault on England which made them scores of new fans if never quite got them to the stellar reaches of the charts internationally, and they remain a legend on the local scene, where songs ‘Dominion Road’, ‘A Thing Well Made’ and ‘Anchor Me’, among many others, remain crowd favourites.

McGlashan’s perspective is informed by the experiences he had in that band, so don’t go asking him where he thinks he fits into the scene. “I’ve never been terribly good at that aspect of the industry where you work out where in the hierarchy you might be. And when I have attempted to do that, it’s done my head in. There were periods of The Mutton Birds, in Britain, where it was a sort of double whammy in that the reason for us being there was to have a shot at it, have a shot at doing well, not on my terms but on the industry’s terms. That was the premise on which I inveigled everyone to put their energies into the whole project. So that was one half of it, and the other half of it was being in England where everything is discussed from the perspective of a hierarchy. Every aspect of British life is class-ridden and rock and roll’s no exception. Everyone’s talking about which band is slightly above the ladder of which other band. And all of that really got me down.

“Thinking about where I fit into things … that experience made me think that it’s best to just kind of wake up in the morning and think about what I want to write and then write about it, and then put all my energy into how exciting it is to realise that idea I’ve had, who I’m going to do it with, and then how I’m going to get it onstage in front of people. It doesn’t matter how many. And then, having done all that, go to sleep happy at the end of the day. And there’s not much room in that day for thinking about what posterity’s going to think about the whole process.”

McGlashan wasn’t exactly brimming with self-confidence when he returned to New Zealand after The Mutton Birds.

McGlashan readily admits that he wasn’t exactly brimming with self-confidence when he returned to New Zealand. “I was pretty beaten after coming back from Britain. I really felt I’d failed. I don’t think that now, but from an industry perspective … obviously, there’s numbers, you go over there to sell hundreds of thousands of records and you sell 5000 records, it’s unequivocal, and Virgin Records dropped us, so …”

He came back and started writing but didn’t know where it was going to go. “To feed the family I wrote some music for TV. I was doing a long-running TV series and although it was an enjoyable and creative process, and I learned heaps from it, I felt all this sense of … it’s possible in this business to talk yourself into a division, a set of divisions where people can’t jump out of one box and into another. If you do X you can’t do Y, and there are plenty of people who will help you talk yourself into that state. And at that stage I was kind of talking myself into it without any help from anybody else.”

McGlashan credits his friend, fellow singer-songwriter Sean Donnelly (aka SJD), with helping to re-engage with his essential creative urges, and a residency at Auckland University’s English Department also nourished those urges.

“They said, ‘Do you want to be writer-in-residence for your songs?’ Which was amazing, and I started working on some long-form songs, nothing to do with trying to be commercial, the anti-Mutton Birds in England. The stuff I was writing over there wasn’t that commercial but there was certainly a sense … an imperative in me that said I should be writing short, snappy things. But when I got back home I started reading Yeats and all these myths about Ireland and Scotland and about how people have stories of intermarriage between sea folk and man-folk, and I started pissing around with that and wrote ‘Passenger 26’, which is this really long-form song that ended up on the first solo album. And then it was just like getting my strength back and doing what I wanted to do. And with good support from people like Sean, and good experience with gigs, I realised I had to keep doing it. I needed to keep doing it anyway, because I’m not very good to be around when I’m not writing, or if I think I should be writing something and haven’t got to it yet.”

Having managed just three solo albums in 19 years, McGlashan is aware that he’s not exactly prolific, but that’s of little consequence to him. “I’m not that prolific with my own songwriting, but that’s what I’m on earth to do, I think. I lose faith every so often and there were times when I was trying to keep the family fed where I noticed that I was really kind of waiting for the phone to ring, waiting for someone to ask me to do something else. Not only because there would be a fee attached and there could be groceries that could be bought with that fee, but also that I didn’t have to think about the song that I wasn’t writing.

Don McGlashan, Bar Bodega, 7 March 2012 - Photo by Wendy Collings/Tymar Lighting

“But I’m now I’m at the stage where I can feel quite blessed in that through all of that, through all the pragmatism and self-doubt, I’ve never stopped percolating the songs. And if you add all that up over time, it’s a body of work that I’m proud of, and I think anybody would be proud of it even if they hadn’t done all the other stuff. If somebody had worked only on those songs, it’s a decent amount of stuff. It’s not as many songs as I would have liked to have written. Maybe having a slow output and lots of distractions and lots of needs to step sideways is actually not a bad thing and maybe I could have disappeared up my own bum. Maybe I would have written 17 Celtic myth songs and they’d have all been tragic and awful. All I know is that all the sidestepping has put a roof over my kids’ heads and I’ve survived doing only music in this place.”

While McGlashan is well aware of the difficulties surviving in a small market like New Zealand, his appointment from 2010 to 2016 as New Zealand writer-director on the board of APRA – where he saw how glossy and well-resourced the Australian music scene is – made him aware of the cultural advantages of working outside of that commercial system.

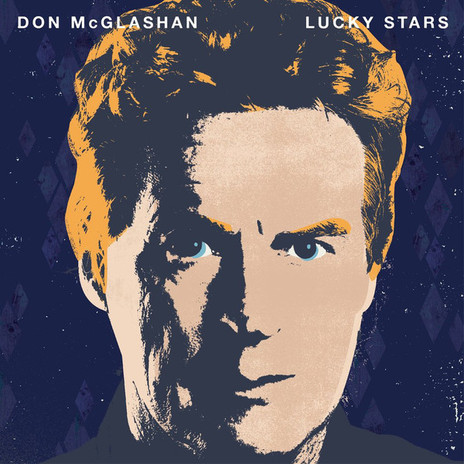

Don McGlashan - Lucky Stars (2015)

“I guess I’ve always been a cheerleader for that approach which prioritises or privileges the work as a piece of art over a commercial entity, but of course I would say that because I’m not that popular. In New Zealand there are lots of different avenues for people to get their work out; there’s not just one gate through which everyone has to pass, which is really good. I always used to say ‘the gravy train doesn’t really stop here’, and in a way that’s a good thing.

“I get an email from Graeme Downes every so often saying, ‘I’m writing a song now and I feel like it might be talking to one of yours’.”

“I think that it’s useful to have somebody like me saying writing is important – and writing well is important – and when I get an email from Graeme Downes [The Verlaines] every so often saying, ‘I’m writing a song now and I feel like it might be talking to one of yours,’ I feel great about that because that’s what we do, we’re trying to describe this place, we’re trying to describe ourselves, and we’re listening to each other as we do it.”

As for the occasional criticisms that McGlashan has faced for building local iconography into his songs: “It used to bother me when people would look at the way I use local detail and then put me into a dinky-die nationalist box. It meant they weren’t listening because it’s a peripheral detail about the song. But then after awhile, I realised you have no jurisdiction over how deeply or shallowly people listen to your stuff, and neither should you, and therefore the only thing to do is to shove it out and keep your head down.”

His writing has continued to evolve. Reviewing his 2015 album Lucky Stars in Metro magazine, I wrote: “All the hallmarks of his singular style are in place – the spine-tingling way he moves from major to minor keys, his keenly observational eye, the thoughtfulness with which his songs are forged.” A great example cited is the album’s title track, an “imaginative pontification where the writer finds himself before dawn at a petrol station in Henderson, gazing at the stars and marvelling at the fact that he’s got a body that does everything it’s supposed to do, and ‘all the bits that make a man.’ No one else gets close to writing songs like that, and making them work.”

Certainly, his 2016 tour with Shayne Carter – often performing lesser-known songs – and last year’s extensive tour, in which McGlashan rose to the task of reinterpreting a career’s worth of material, helped to dispel those criticisms, as the sometimes ramshackle and always spontaneous performances brought new tangents to old songs.

“I try to get on the road quite often and in between albums I’m learning that there’s a lot of cool things that I can do. I can do a collaborative project, like the two alternating songs projects I’ve done lately with Dave Dobbyn and Shayne Carter. Dave and I did a church tour where we chose each other’s songs from the back catalogue, and that’s a way of getting in front of people, and giving them a show that’s not like your normal show, and it’s also a way of learning lots of stuff on the road and to grow as an artist, and both of those have been two of the best tours we’ve ever done in terms of being challenged and being fun.

Don McGlashan, Bar Bodega, 7 March 2012 - Photo by Wendy Collings/Tymar Lighting

“I guess with people like Dave and Shayne shining a strange torch into my attic, songwriting-wise, it made me think: what about if I put a show together that wasn’t what people expect? Maybe a show where there were some songs which hadn’t seen the light of day or songs which, when paired up, they talk together in interesting ways. And at times, in the middle of a show, I thought maybe I’ve got to a place now where I can just go, ‘I am who I am, these are some songs you may or may not have heard, and I want to sing them to you’. And then people lean in, rather than previous times where I might have been thinking, ‘What do you want to hear? These are the ones you probably know.’”

In February 2022 McGlashan released his fourth solo album, Bright November Morning, featuring his band The Others – Shayne Carter, Chris O’Connor and James Duncan – with guest appearances from Hollie Smith, Emily Fairlight, Anita Clark and The Beths. Bright November Morning debuted on the New Zealand Recorded Music Album Charts at No.1.

--