In the first part of this story I looked at how the mix of underground and DIY guitar bands collided with Christchurch’s throbbing dance scene to influence a cohort of bands who successfully fused the two: the Shocking Pinks, Pig Out, and Bachelorette. In this part, I’m going to consider the influence that these bands, and the buzz of the scene, shaped the bands that followed them.

The Tiger Tones were formed by Mark Holland, Ashlin Raymond, and Andy Frost, with James Grant joining later. Apart from Frost, who was always behind the drum kit, the other three members often switched between guitar and bass, with Holland and Raymond alternating vocals, and Holland also playing synth. They were really young – literally straight out of school, and really accomplished musicians who were also huge Shocking Pinks fans. In fact, the common thing that they mentioned when I first met them was the influence on them of that first Shocking Pinks album.

Photo from an early Tiger Tones show at a house party, L to R: Ashlin Raymond, Rob Martelli, Andy Frost. Rob Martelli played guitar with the Tiger Tones on occasion, before forming Not So Experimental. - James Dann

Aside from the Shocking Pinks, they were also influenced by the Gang of Four, The Rapture, and Underworld. While their early recordings sound more like Joy Division, by the time their record came out you could tell they were channelling New Order. After winning student radio station RDU’s RoundUp competition in 2006, Tim Baird signed the band to his Pinacolada label. “I’d seen them play a few times, and actually applied for a Creative Communities grant to do an album with them without actually asking the band first – I figured that they’d be hard pressed to say no if I already had the money to pay for the project. Thankfully the band were into the idea, and the album was recorded late 2007, with a large burst of it also recorded in February 2008.”

After a couple of brief tours, The Tiger Tones broke up shortly after their album came out in 2008. “It’s a pity that later that year they pretty much imploded as they are very gifted songwriters and players,” says Baird.

The Tiger Tones on tour in Picton. From left: Mark Hollan, James Grant, Ashlin Raymond, Andy Frost. - James Dann

The presence of Nick Harte was still strong around this time. Members of the Tiger Tones often played with him at live Shocking Pinks shows, and he helped to produce and record an EP for Not So Experimental. Not So Experimental was a four-piece, screamo-hardcore group that had found kindred spirits, if not a similar sound, within the scene. Despite the apparent contrast in sounds, they would often find a way on to bills for shows at the Dux, where their raw energy was always a hit.

Bang! Bang Eche! at NYC's Piano's Bar, 2008

Another band of note to emerge from this haze was Bang! Bang! Eche! Formed in 2007, they were almost comically young, which made their early shows a nightmare for promoters, as each of the members had to come with a parent or guardian. Initially a six-piece, they built on the punk energy of The Shocking Pinks, the rave stabs of Pig Out, and the melodic sensibilities of the Tiger Tones to create something that was uniquely theirs. They entered and won RDU’s RoundUp band competition in 2007. As brash and up-front off-stage as on it, they were soon touring Europe and the States as a four-piece (Charlie Ryder, T’Nealle Worsely, James Sullivan, Zach Doney). Though they were from Christchurch, they were very soon too big for the place. However, their footprint on the local scene was so large that they even had their own parody band – Blast! Blast! Noise! – a two-piece who lovingly skewered the sound and aesthetic that BBE had created.

Bands made up of young members was a recurring theme, which is a sign of the energy and exuberance that was bubbling up through the scene at this time. Black Market Art was a great example of this. Formed by three friends – Matthew Scobie, Darian Woods, and Joseph Harper – all from Cashmere High School, they had been playing the odd spaces that you play when you can’t get into pubs. Venues, said Scobie, “like libraries, churches, random parks and stuff for all those sort of youth events and fundraisers. Our influences started like any high school rock band in the early noughties, The Strokes, The White Stripes, and then (early) Kings of Leon a bit later. Then we started playing Beatles and Doors covers.”

Charlie Ryder and Perry Mahoney from Bang! Bang! Eche! at the Dux de Lux, 2007. - Chris Andrews

Sill at school in 2006, their media studies teacher was Richard James. Mr James, as he was of course known to his students, had been in a number of bands dating back to the late 70s, including Mainly Spaniards. Darian Woods remembers that one of the projects for the class was a history of Flying Nun, and as part of this, Black Market Art recorded a cover of The Clean’s ‘Point That Thing Somewhere Else’. As well as this literal schooling in the history of Flying Nun, the band were also influenced by acts such as Connan Moccasin, with whom they toured the South Island. Richard James also played couple of shows around this time, and Black Market Art were his backing band, aka Richard James and the Teacher’s Pets. Black Market Art broke up around 2008, when Harper moved to Auckland.

Woods formed Wet Wings with Lucy Botting, released Willow Peaks on Lil’ Chief Records in 2011, and became part of the Wellington band Girlboss. Scobie would go on to play in a long list of bands, including The Hatemen, The O’Lovelys, T54, Valdera, The Undercurrents, Planet of the Tapes. One of the bands that he would play with live was the Ragamuffin Children. Formed in 2006 by Brooke Singer and Anita Clark, this duo played a much-more sedate style of folk music than many of the other bands at the time. Singer would go on to form French for Rabbits, whilst Clark would play in a number of bands, including The Eastern and Devilish Mary and the Holy Rollers, before starting her own solo project, Motte.

Poster for 2007 show at the Dux de Lux with Bang! Bang! Eche!, the Tiger Tones, and Ed Muzik. - James Dann

At the louder end of the spectrum was a band called the Insurgents. Frequently playing all-ages shows at venues including Zebedees, or at Out of Kilter parties organised by Will Edmonds, the band was formed in 2004 by Chris Young, David Coffey, and Mike Ellis. They had a quiet year in 2006, as much of Young’s energy was focused on his other project, Neil Robinson, who won that year’s smokefreerockquest. Following this success, he turned his attention back to the Insurgents, recruiting Edmonds into the band.

In May of 2007, a tragic incident at a party in Christchurch resulted in the death of Young’s sister, and he channeled much of his energy and focus into writing a playing with the band. This led to 2008’s Yours Disappointedly EP, and a post-breakup album, 2009’s All The Stupid Smiling Faces on Failsafe Records. After the Insurgents broke up, Young moved to Wellington and formed The Eversons, who released a couple of albums on Lil’ Chief, and is currently part of Superorganism, signed to Domino Records.

Poster for a 2005 show at the Wunderbar, featuring Charlie Ash, Ed Muzik, and the Insurgents. - James Dann

As the primary local radio station, RDU played a key role in broadcasting this music, and the promotion of the shows. But this was largely driven by hosts of individual shows, rather than the station management, which was still more invested in the dub-roots scene that was in favour nationally. (At one point in the 00s, the station manager was Hat, the “anarchic drum-thrashing accountant” from Squirm.) Tim Baird had a long-standing connection to the station, and had been on and off air since his time as programme director in the early 90s.

The programme director at this time was Benet “Dr” Hitchcock, who was also the driving force behind the Mixtape Connection series of parties. Starting in mid-2005, these brought the best of the current indie, electro, and dance tunes into an underground bar, Capitol, which had been a bank vault in a former life. Though they initially only had a short run, the popularity of these parties meant that they would often be revived in subsequent years. Aside from Dr Hitchcock, other DJs included the Shocking Pinks, Ed Muzik, and a live set from Pig Out. One of the other Mixtape residents was Richard MacFarlane, one half of RDU’s Guitar Media show, which was another strong advocate for local guitar music. The best show on the station in the 2000s was The Joint, on Saturday afternoons. Hosted by Fraserhead and the Herb Whisperer, who were good friends with Tim Baird, this show would often be the first place you could hear songs from bands on Pinacolada, or guest DJ sets from the artists.

Pig Out performing. Kit Lawrence on the speaker, Fraser Austin on bass, Marie Celeste on synths, Nick Harte (seated) on drums. - James Dann

It’s almost hard to imagine now, but The Press had a really good weekly music section that would come out each Friday. Run by Vicki Anderson, it had interviews with local and touring bands, as well as reviews of new records. There was also a live music column written by Miriama “the MZA” McDonald, which would run the ruler over the gigs – good and bad – and the comings and goings in the scene.

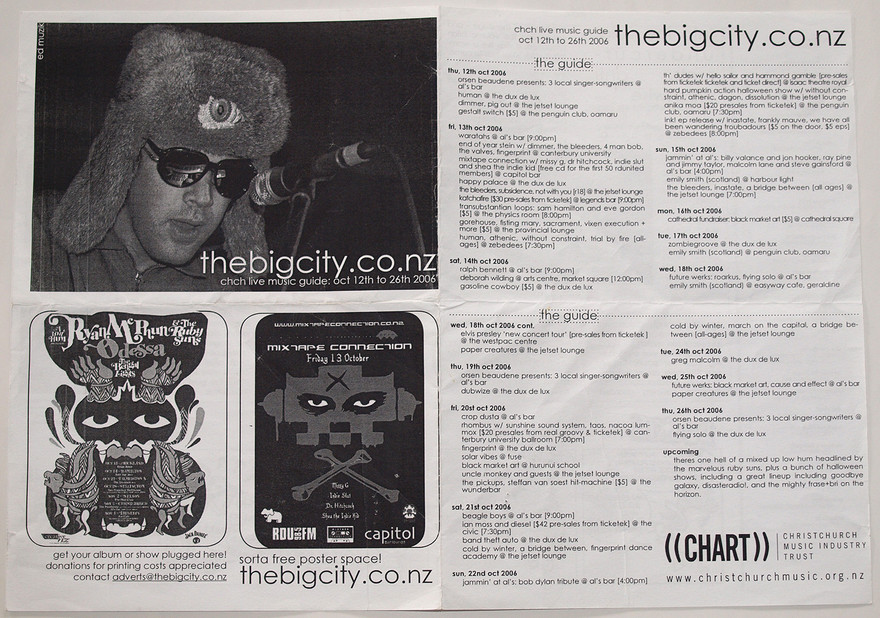

Another who wrote for The Press was Chris Andrews, although this wasn’t his primary outlet. Alongside being a member of a ridiculous number of local bands, he launched a zine, The Big City. An avid gig photographer, he and his camera were an almost constant presence at any gig worth going to in this period. With one of his photos from the previous week on the cover, he’d print off around 60 copies and distribute them at venues like the Dux and the Media Club. There was a gig guide, which would often feature over 30 gigs in a week (a number that is frankly hard to fathom in the Christchurch of 2018). With his collection of live photos, posters for shows, and gig reviews, his website thebigcity.co.nz is an invaluable resource for anyone wanting to know more about the shows at the Jet Set Lounge, or all the members of the Palace of Wisdom.

Copy of The Big City zine from 2006, with Ed Muzik on the cover. - James Dann

It may seem vaguely quaint now, but the power and affordability of computers was having a major impact on the way musicians, especially those with a DIY bent, could record and release music. It was easier than ever before to record songs at home, to mix and master them, and to distribute them. CD burners were cheap enough for most people to be able to burn off at least a rough demo EP. MySpace was a vital platform for the building links between bands, booking tours, and discovering new groups. Music blogs were starting to break down geographic barriers, and artists could connect with like-minded souls even if they were in different time zones or hemispheres.

Kris Taylor from Pig Out, playing in the crowd at the Dux de Lux, Christchurch, October 2006. - Chris Andrews

And while all these fancy new developments were happening, the local record store was still vital. In Christchurch, this was Galaxy Records, which was on High St at the time. Owned and run by Dave Imlay from Into the Void, it catered for all sorts, and was always abuzz with a unique mix of wannabe DJs and indie kids trying to push their self-released CDs. Tim Baird used to work there, and remembers its importance. “Galaxy was a fundamental part of the local music scene – The Shocking Pinks album cover graphic is actually taken from a graffiti stencilled on one of the supporting columns outside the old store on High Street, which speaks volumes of how well-respected the store was within the musical community.”

Any scene tends to coalesce around a handful of key venues, and at this time perhaps the most important was the tavern bar at the Dux de Lux. In the south-east corner of the Arts Centre precinct, this building hosted the student cafeteria when the University of Canterbury was still in town. After the university moved to Ilam it had a brief stint as a creche, before the Dux moved in and became one of the pre-quake city’s most loved hang-outs. They brewed their own beer, and had a pescetarian menu well before craft beer and veganism were common terms. The success of the bar and the restaurant meant that front room – known as the tavern bar – could host live music four or five nights a week. If patrons didn’t like the band, there were two or three other parts of the venue they could use. There were two things that made the Dux unique for bands: you got paid, and there was never a door charge. Of course, you got more for a Friday or a Saturday than a Wednesday or Thursday, and you had to pay a sound engineer and the support bands, but still, a guarantee was a shot in the arm for most band accounts.

Die! Die! Die! playing at the Media Club, Christchurch, 2006. - Chris Andrews

Another important venue at this time was the Media Club at 191 Armagh St (now part of the Margaret Mahy playground). Built several decades ago as a social venue for journalists and reporters, by the 2000s it was being utilised by bands. It was a beautiful, ornate space that had seen better days, and had an air of decay about it. Nick Harte remembers it fondly in an interview for Pitchfork: “There are some quite unusual venues in Christchurch. There’s a venue called The Media Club and there’s two bars in there; and one’s like a private-function room that looked like it was built in the 1930s or 40s and it has chandeliers and mirrors – we call it The Blue Room. And the first 10 Shocking Pink gigs were there and the last few have been there as well. We’ve seen some great touring bands play there as well. I really love the sound; it’s a great place to record live gigs.”

The Jet Set Lounge, formerly the Southlander, on the corner of St Asaph and Madras St, was a popular spot, especially for larger touring shows. Across in Lyttelton was the Wunderbar, which because of the necessity of people having to carpool through the tunnel, would have very hit-and-miss shows; if no one made the effort, you could be playing to an empty room, whereas if people had made the drive, you knew that you’d have them for the night, and the show could fairly rapidly get raucous. It is also worth mentioning the all-ages shows that were put on. There were a couple of all-ages venues – Zebedees in Sockburn, and Fuse in Sumner – as well as other spaces that could be adapted. A number of bands were amenable to playing all-ages shows, and Blink would often try and book both all-ages and R18 shows for his A Low Hum tours. The support for these shows, especially in 2004 to 2006, was really important for some of the kids who would then go on to start their own bands and record labels.

The Renderers at the Media Club, Christchurch - Photo by Alistair Reid

From around 2005, the area around High St, Tuam St and Lichfield St in the southeast of the central city was re-energised by boutique fashion stores, cafés, art galleries, and venues. Attracted by the cheap rent, there were also plenty of ramshackle places for artists and musicians to have studios. In mid-2005, the Shocking Pinks and House of Dolls played a show in one of the buildings that became SOL Square, a hip complex of bars and restaurants that was the new hot spot for people heading to “town” in the years running up to the quakes. (One of the other bands that night was the New Originals, which featured Tim Moore. Aside from being the brother of Johnny Moore, Tim was a key member of Von Klap, the band that probably best bridges the mid-2000s indie scene to the Lyttelton Folk sound that defined post-quake Christchurch.)

Next door was a tiny bar called Cartel, which was too small for bands to play, but gave Johnny Moore the confidence and the capital to open Goodbye Blue Monday. This bar, often known as GBM, was a block away from SOL Square in the Poplar Lanes area. Significantly larger than Cartel, it had a small stage indoors that frequently hosted bands and DJs. As well as the music, the cheap drinks ($3 red wine) and ability to smoke outside under the cover of the giant balcony meant that this was the go-to place for scenesters up until the bar’s untimely demise in the earthquakes. Post-quake, Moore and his family are back with a new bar on almost the same site, Smash Palace, which features live music on the odd occasion, including a notorious St Patrick’s Day leer-up.

Flyer for World In Motion, a 2005 show featuring the Shocking Pinks, the House of Dolls, the New Originals, and Self Titled, in a venue that would become His Lordship’s Lane. - James Dann

Outside of the more conventional venues, house parties were always an important part of the scene, especially for the younger bands and their fans, who couldn’t get into licensed venues. They also had their disadvantages. Sound was always an issue: at a house party in Dunedin, which was Bang! Bang! Eche!’s first show in the city, I had to stand holding an RCA cable in a certain position for their whole set to ensure that the synth stayed plugged in. There was also the risk of being broken up by the police or noise control, as happened a couple of times at parties held in houses in Christchurch’s inner east. In early 2007 I threw a sizeable house party at my parent’s place. We had put up a marquee for my brother’s 21st the next night, so I asked a few of my favourite bands to come and play: the full line-up was the Tiger Tones, Frase and Bri, Not So Experimental, Get Set Play (the solo side-project of Mark Holland from the Tiger Tones), Ed Muzik, and the Shocking Pinks. The invitation asks people to “myspace ed for directions”, which shows the importance that social network had at the time. (Unfortunately, gate-crashers at the party stole all the beer for the next night’s 21st.)

T'Nealle Worsley from Bang! Bang! Eche!, 2007. - Chris Andrews

There was a large overlap between the contemporary music and arts scenes at the time. The area around High St and Poplar Lane attracted artists for the same reason it attracted musicians: affordable studio space. There was a great concentration of art galleries around this area, with at least a couple – the High St Project and the Physics Room – which would host musical events on occasion. Many of the band members were at art school at Ilam, and this influenced the design elements for posters and record covers.

Exhibition of Garage Collective posters at High Street Project, 2007. - Chris Andrews

Jared Davidson was a Christchurch-based designer whose screen-printed posters under the name Garage Collective rapidly became very sought after. In 2005, the High St Project hosted an exhibition comprised entirely of his posters, and in early 2007, the Physics Room had a Kit Lawrence solo show. Lawrence had done much of the artwork for the Shocking Pinks, as well as his own band, Pig Out. As with the Christchurch scene in the 80s, when an artist like Ronnie van Hout had done posters for The Pin Group and played in Into the Void, the creatives felt free to express themselves in any media that took their fancy.

Poster for 2007 show at the Dux de Lux with Ed Muzik, Jimmy Zoom and the Baytown Grifters, and the Insurgents. - James Dann

Whatever energy the scene had largely petered out by 2009. Pig Out moved to Auckland, where they were getting deeper into underground club music. The Tiger Tones split, and Nick Harte’s long-awaited record on DFA never really happened. The quakes were the definite end-point, with the best of the venues – the Media Club, the Dux, the Jet Set, Cartel, Goodbye Blue Monday – either destroyed or severely hampered. It is always dangerous to look back nostalgically and only remember the high points of a certain time and place. However, the Christchurch of this period doesn’t exist anymore. Though we didn’t think the city was anything special, it had a number of unique things going for it, things that we didn’t realise until the quakes took them away. It was a sound that came from the city, especially the grittier, more run-down parts of the south-east of the CBD, where rent was cheap, where artists and musicians and bartenders and baristas all bumped into each other on the street.

Bang! Bang! Eche! pose after winning Round Up 2007. - Chris Andrews

Many people from these bands did go on to other musical projects. Charlie from Bang! Bang! Eche! formed the intercontinental pop-group Yumi Zouma with Josh Burgess from Sleepy Age, whilst T’Nealle Worsley, who played bass in BBE, helped to start the Darkroom bar, which remains the cornerstone of the Christchurch indie music scene. James Sullivan, also from BBE, has played in a number of important post-quake bands, especially those on the Melted Ice Cream label. Richard MacFarlane from Guitar Media started the Vancouver-based vapourware label 1080p, which has released a number of important electronic records, by acts such as Mark Wundercastle (Mark Holland from the Tiger Tones) and Abstract Mutation (James Grant from the Tiger Tones).

Of course, a number of great artists have come out of Christchurch, and especially Lyttelton, since the earthquakes. The quakes sent bands back into their garages, and turned gigs into house parties. The music that came from this period is an article for another time, but it was simpler: more direct, less decadent, detached from the ironic detachment. Artists like The Eastern, Delaney Davidson, Marlon Williams, Nadia Reid (who once opened for Ed Muzik at the Wunderbar), and Aldous Harding have gone on to achieve great things. Also, success isn’t the only indicator of quality: the post-quake garage scene in the city would be particularly strong, with bands such as Wurld Series, T54, The Transistors, The Salad Boys, the Dance Asthmatics, and many others released by Melted Ice Cream Records.

Delaney Davidson. - Sabin Holloway

The mid-2000s music scene in Christchurch was one that was vibrant and unpredictable, with a DIY ethos that prioritised musical quality, rather than strict genre boundaries. It was created in a city that soon wouldn’t exist, though none of us knew it at the time.

All of these bands had songs that referenced cities and places, frequently in the context of wanting to be somewhere – anywhere – other than Christchurch. They were fighting against Christchurch: or at least, the staid, conservative image Christchurch had. Us against the city indeed.

Read Christchurch Indie: Us Against the City, part one

--