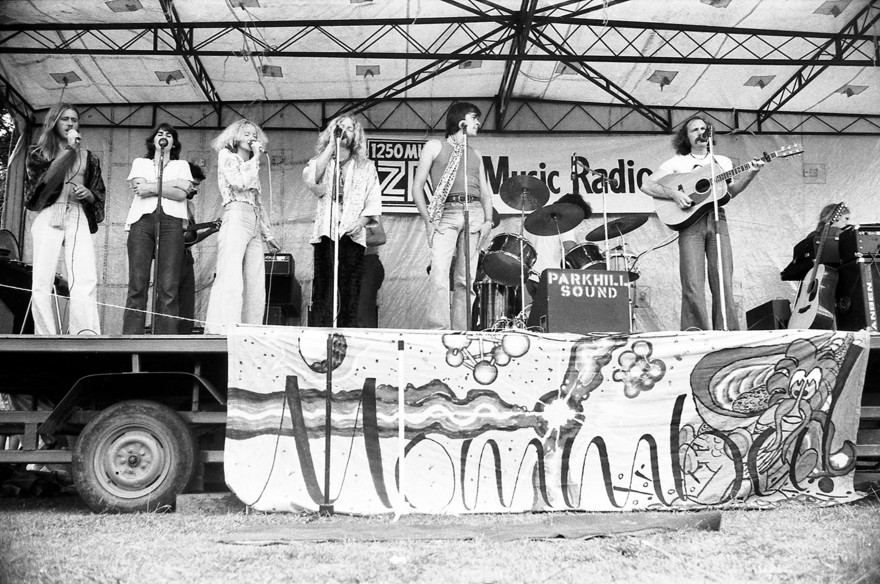

Aerial Railway stage at the second Nambassa festival, 1979. - Photo courtesy of Fat Family Chronicle

In the midst of the western world’s 20th century counter-culture awakening, a significant number of young New Zealanders turned their backs on conservative suburban life to explore new ways of living. During the 1970s and 80s several collectives were established on farm, bush and back-block land, but the Moehau Community, with bases in both Port Charles on the Coromandel Peninsula and Ponsonby, Auckland, was the only one to spawn an audio-engineering course, a mobile studio, a composition and recording programme in schools, and legendary side stages at the Nambassa and Sweetwaters festivals. This hardworking, good-natured collective was known as Aerial Railway.

Early days and the Moehau Celebration

In 1971, things were changing for David Calder. “After I left The Hamilton County Bluegrass Band, Ray Columbus set me up with a free trip to England on a Greek cruise ship. I only had to sing a song a night at the cabaret. My ambitions were not bluegrass, I wanted to chase my own music. I went to France because I had an honours degree in French and I burned to see Paris as much as London.”

After travelling through Europe, Africa and Asia, Calder returned to Auckland and started teaching. At a house in Vermont Street, Ponsonby, known as Peach Prism Community House (or V Street) he met a group of people including filmmaker Roger Donaldson, writer Brigid Lowry and architect David Mitchell. Calder and others from this group including Terry St George, a musician with an architecture degree, and talented pianist Matthew Brown, formed the band known as MOMMBA.

MOMMBA performing at Parnell School with writer Brigid Lowry in the foreground.

“Mo is from Moehau,” explains Calder, “and the MMB is Magic Mountain Band, so it’s very Ken Kesey and Merry Pranksters without quite so much Kool-Aid Acid Test. I was the only professional musician, so I became the songwriter and musical director.”

Elisabeth Vaneveld (also a member of MOMMBA) had grown up in Canada and returned to her native Aotearoa at 18, leaving behind her family and friends. She had a natural talent for creative organisation. “The people at Vermont Street became my whānau. There was a desire to buy the farm at Moehau so I formed the company and organised the shareholding so we could afford to buy it, and later helped organise the purchase of the house.”

MOMMBA on the 1ZM stage.

In 1976 Johnny Irons had returned to New Zealand after a spell in the UK, where his electronics qualifications from the NZ Post Office won him a job at Gooseberry Studios in London’s Chinatown as assistant engineer.

Aerial Railway's Johnny Irons at Nambassa. - Photo courtesy of Fat Family Chronicle

“One morning I arrived and found the engineer asleep in the drum booth, he looked like he was going to stay there for several days, so I did the session, my first solo one, and it turned out to be for John Cale. He was famous for killing sound engineers, but we got on like a house on fire.”

Irons returned to his old job at the Post Office but it got stale pretty quickly, so when a friend told him of a collective in the Coromandel on 1100 acres of land overlooking Sandy Bay who were involved in music, he thought it well worth checking out.

He arrived at the Moehau Community to find them in the midst of preparing to stage a three day festival. “I came up about two weeks before the show and spent a week doing ground preparations. Somebody found out I did electronics, so I got shoved into this room with a Rasputin-looking chap called Moby who was halfway through building the mixing desk. He was truly happy to find someone that could solder correctly.”

Moehau group, left to right: Shelley Lodge, David Mitchell, Brigid Lowry, Terry Lysaght, Sally Liggins, Penny Hyatt with Pippin, Terry St George, Ian (Ezy) Kemp, Patrick Fleming, Roy Fraser, Roy Emerson (Seated) - Roy Emerson

An organisation in Auckland called Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) was pushing the government to have a royal commission on whether nuclear power would be allowed in Aotearoa. The collective felt strongly about this cause, and the Moehau Celebration was staged to help fund their efforts. The Celebration attracted between 1300 and 2000 people: impressive numbers considering Sandy Bay’s remote location. It featured guest speakers and workshops during the day, with music and entertainment in the evenings provided by MOMMBA and The Mahana Roadshow, a house-trucking band of musicians, entertainers and their families in the vein of BLERTA.

The Mahana roadshow truck.

Moby (Michael Diack) had been involved with MOMMBA for a while. “I was part of a small company, Toad Electronics, making guitar amplifiers and mixers. I built the electronics and amps and we took it on the road, travelled around for about six months doing shows at the Maidment Theatre (on the University of Auckland campus) and various venues around the Coromandel, often in conjunction with the Mahana band. I was always the front-of-house sound person involved in these things.” Ian “Ezy Rider” Kemp, MOMMBA’s drummer, was also a good builder. He did quite a lot of the construction on the collective’s projects.

Aerial Railway sound engineer Michael "Moby" Diack - Candace Bagnall

The Celebration caused a bit of a stir locally. “Down at the beach the police started ‘taking names’ of people who were bathing nude,” says Johnny. “About this time everybody on the festival site suddenly felt very hot and needed to go for a swim, and the police found themselves surrounded by many hundred happy naked people. Game over. The plainclothes police were more fun, they turned up in brown street-shoes, long white socks with a pen and pad tucked in ’em, walk shorts, short-sleeved shirt, camera ... they blended in easily with a crowd that was mostly nude.”

“We built a curious building there from telegraph poles that was called the Aerial Railway,” says St George. “It was the site info-spot, a stairway that sort of aimed up at the mountain. The idea was that the Aerial Railway was a journey to somewhere.”

Aerial Railway structure at Moehau. - Photo courtesy of Fat Family Chronicle

Not long after the Celebration, MOMMBA adopted Aerial Railway as their name and played gigs all over, with various musicians coming and going including Steve Robinson of Tamburlaine and Lou Rawnsley of The Underdogs (Daniel Keighley acted as manager for the band, and filled the same role later for Legs For Fish).

Sleeping Dogs soundtrack, 1977, front cover. Music from Murray Grindlay, Mark Williams, Alan Galbraith, Josie Hamillton Rika, and Aerial Railway. Arrangements were by Murray Grindlay, Dave Calder of Hamilton County Bluegrass Band, and Matthew Brown. Recorded at EMI Studios, Lower Hutt, Produced by Alan Galbraith, engineered by Peter Hitchcock and David Ginnane, remixed and mastered by Peter Hitchcock.

1977 also saw David Calder composing the incidental music for Roger Donaldson’s hit movie Sleeping Dogs at a week-long recording session in EMI studios in Lower Hutt, utilising the prodigious skills of Matthew Brown on piano. Their contributions on the soundtrack album are credited to Ariel (sic) Railway.

Terry St George's house truck Mole Rat with daughter Lucy at Avalon. - Photo courtesy of Fat Family Chronicle

St George shares an anecdote that captures something of this period. “In 1977 our two-year-old daughter Lucy and I hit the road in our 1948 International flat-head straight-six mobile home, named Mole Rat. I think the first words Lucy learned to read were “Hot Pies” from the signs outside dairies. We met up with David Calder for recording at Avalon, where I was mainly involved in keeping the team fed using Mole Rat’s gas cooker. At Marmalade, as part of an 8-track loan arrangement, I recorded ‘Sunbird’. It was an apocalyptic vision of a damaged Earth, narrated to music by Matthew Brown, with help from Michelle Scullion and others. The Sunbird flies to the sun, sacrificing itself to bring colour back to Earth. Pretty heavy stuff in hindsight!”

Nambassa

After the success of the one-day Waikino Music Festival which drew over 5000 people later that same January (where MOMMBA performed along with Living Force, Hello Sailor and Th’ Dudes) the principal organisers got together and brainstormed: how to tap into the wave of enthusiasm for music-based counter-culture gatherings?

Peter Terry, organiser of the Waikino festival, had begun working towards the first Nambassa festival. He recalled to AudioCulture: “As there had been some niggly feeling at Sandy Bay community that Nambassa was becoming central to the counterculture movement, during the Moheau celebration of 1977 at Sandy Bay, which I attended, I approached Elizabeth Vaneveld from MOMMBA to see if she’d like to organise and manage a second stage at the forthcoming Janurary 1978 first Nambassa festival. The olive branch was extended. It had become clear that our main stage was not going to accomodate the number of performers wanting to play Nambassa. Hence Aerial Railway was then born in earnest.

“Nambassa supplied all the performers on Aerial Railway 78 and 79, including most impromptu performances. The Aerial Railway group were employed as stage managers at both events. Moby supplied the sound system for Aerial Railway. They designed and handcrafted their own stage which was primarily built by Nambassa teams.”

And so January 1978 saw the first Nambassa Festival at Phil and Pat Hulse’s 400-acre farm on Landlyst Rd in Golden Valley, with up to 15,000 people in attendance to see Australian band Skyhooks along with locals Midge Marsden and Living Force – and also to see each other; this was a full-on gathering of the clans.

Mahana band at Nambassa Festival, 1979. - Candace Bagnall

Elisabeth applied her organisational skills to artist management and programming. “An important part of the Aerial Railway Stages’ success was the focus on New Zealand creatives as a whole, not only music. We had dance, poetry, spoken word, a little bit of theatre, a lot of children’s programming. I recall it all had its own kind of rhythm and worked really well – everybody on the crew side in their particular role had that x-factor skill that they were able to apply very collaboratively. Extraordinary, really.“

Limbs Dance Company on Aerial Railway stage, Nambassa festival 1979. - Photo courtesy of Fat Family Chronicle

“We offered a ticket to the festival if people were prepared to deliver something on stage. This produced some crazy performers, but they were usually well received,” says Terry. “A few of us would form a new band each year and do a set just to experience the fear and exhilaration of playing in front of lots of people. We’d always change the name; Legs For Fish, General Public, Friends of The Management ... as Legs For Fish, we toured with Top Scientists (featuring Rick Bryant) and played university orientation gigs.”

Aerial Railway Stage blackboard, Nambassa Festival. - Photo by Bruce Jarvis

“All in all, the consensus after the first Nambassa was if we had known what we were getting ourselves into, we never would have gotten out of bed,” says Johnny. “The fact we lived through it is quite amazing.”

From left: Terry St George, Drew Seigert on guitar, Leonie Thoms with flute, and an unidentified friend.

The Nambassa Winter Show was a multi-housetruck touring circus based out of a pre-production camp at St Johns Youth camp at Langholm, West Auckland. It featured a double-bill of musical theatre: ‘The Mahana Rock Opera’ penned by Billy TK (The Human Instinct), Cadzow Cossar (Moana And The Tribe) and Mahana, and ‘The Return Of The Ancients’ written by Peter Terry. The show was performed in major theatres in Auckland (His Majesty’s Theatre), Hamilton, Napier and Wellington, plus a few impromptu gigs at prison farms and in Waihi. The Mahana band also featured Corben Simpson (BLERTA) and Mahia Blackmore (Meg and the Fones).

Nambassa 79 was massive, with up to 65,000 people attending the three day festival. The distinctive Aerial Railway stage design for the 1978 and 79 Nambassa shows was by Mike Heybrook and Terry St George. A low apron in front of the stage was the public access area.

Terry St George and Johnny Irons at the Moehau farmhouse. - Photo courtesy of Fat Family Chronicle

“For a small country we are exceedingly well stocked with people who are prepared to stand on their hind legs and poetise,” says Johnny, “It’s very easy to get a poet on mic, noticeably harder to get them off. Moby had a fine response, with the toyboxes on the mixing desk he could turn the most ardent poet into a Vogon with a flick of the switch.”

Of note on the Aerial Railway stage in 79 was Limbs Dance Company in one of their early public appearances, and all-female band the Vibraslaps.

As if the workload wasn’t already large enough, calamity struck at the last minute. Headlining alongside Little River Band and Golden Harvest) was Split Enz. They had just returned to Aotearoa from their first long spell overseas and were keen to do a killer set for the huge home crowd. They booked themselves into the Waihi Hall for warm-up rehearsals and Aerial Railway was more than happy to let them use their mixing desk and other outboard equipment. The hall caught fire, destroying most of the band’s instruments along with all Aerial Railway’s gear.

With only days to go, Moby managed to have a completely new custom-made setup in place when the gates opened. How?

“I had a nearly finished PA, mixing desk and various amplifiers and bits and pieces that I’d designed and built in Auckland for Mahana. Very fortunate, complete serendipity. Put my head down, finished it, took it down to the site.”

St George says, “People talk of Moby as having sparks coming off his teeth. When a cable failed, he sometimes wouldn’t bother to unplug it, just put it in his teeth and strip the plastic off and put a new end on it, plug it straight back in and keep going. Yeah, he’s a legend.”

It’s worth noting that Moby’s Aerial Railway stage mixing desks output stereo sound at a time when other PA systems in New Zealand were still mono.

An exhausted Aerial team returned to the Coromandel carrying a strange memento of their adventures. The fire had melted the mixing desk, which had run through cracks in the floor and into the basement where it solidified into a blob of melted aluminium, with embedded steel bits and faders poking out. This became known as “the relic”. Nambassa had returned a significant profit and announced a hiatus, planning to return in 1981.

--