Gareth Shute recounts writing Hip Hop Music In Aotearoa.

Picture this: the foyer area of a high-rise apartment building in Singapore and four kids are breakdancing on the polished concrete floor – mostly robot moves and short-lived backspins. There’s an Indian kid, a Chinese kid, an African American kid and me – a skinny white kid - all of us about nine years old. Then an older Hispanic kid arrives and interrupts the circle to get down into a handstand, knees bent, before lowering himself onto the crown of his head and precariously swivelling himself around – turning once, twice, before toppling. The other kids yell with surprise and joy.

Gareth Shute (right) as a nine-year-old breakdance fanatic, with his father (Gordon) looking less than impressed

A year later, my parents moved to Auckland’s North Shore (we’d previously lived there and in Gisborne, though I was born in Canada). I began searching for whatever threads of rap music I could find, instantly fascinated by local variants like ‘E Tu’ by Upper Hutt Posse. When I reached high school, I befriended the only other hip hop fan in my class – a guy called Marek Sumich who went on to play the rapping character, ‘Dr Urban’, on What Now. I bought whatever local rap CDs that I came across and went to any gigs I thought I could get into – like Leaders of Style (AKA Urban Disturbance) at The Powerstation spraying silly string into the audience or Lost Tribe playing Shadows bar at Auckland University, with Johnny Sagala joining the small crowd on the dancefloor to comically bust out the running man.

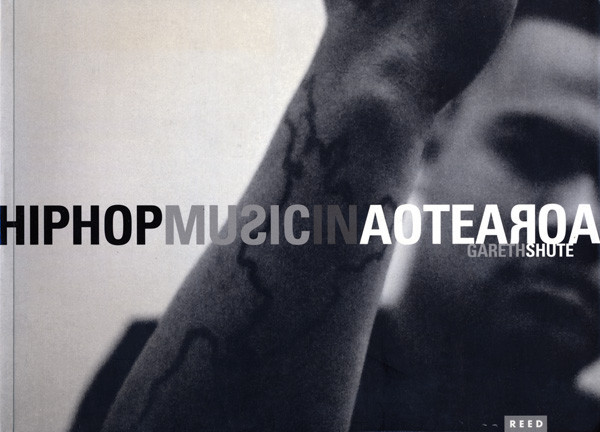

By 2003, the hip hop scene had progressed to a point where a breakthrough seemed imminent – Che Fu and King Kapisi had laid the groundwork and P-Money’s solo album had followed them in reaching a wider audience, not to mention the rise of Dawn Raid in South Auckland. I’d been more interested in writing fiction up to that point, but suddenly it struck me that I could write a book about local hip hop instead. It was slightly insane idea since I didn’t actually know any of the artists or have any published work aside from articles in Craccum and a couple of stories/ pieces in literary magazine, JAAM.

Luckily I knew a guy, Sam Hill, who worked at Reed Publishing and he arranged for me to meet Peter Dowling, a sympathetic editor who said that if I could write a decent sample chapter then they’d consider doing a book. Behind the scenes, Sam told me that one of the other editors later said in a meeting that “hip hop fans don’t read” so it was hardly a done deal.

I also had to work around the fact that I was fairly skint at that time. I worked three days a week at the public library in Avondale and ended up borrowing a cassette dictaphone and a film camera off my ex-girlfriend to work on the book. The camera had no flash, so I’d be up late at night in some club and had to wedge myself against the speakers to stay as still as possible then wait until the person I was photographing stopped moving for a split second so I could capture them without it blurring. The next day, I’d be at work exhausted and often ended up crashing out on the couch in the tiny staff room. A couple of times, I was so fast asleep that I woke to find that my fellow staff had kindly closed the curtains and shut the door.

King Kapisi

I decided to start at the beginning so the first person I tried to interview was Upper Hutt Posse’s guiding force, Dean Hapeta (AKA D Word AKA Te Kupu). The phone rang, but there was no answer and for a few minutes I had a crisis of confidence. Did I really think I could write a whole book on hip hop? I’d emailed Dean to arrange a time, but he wasn’t even home to take the call. I had to grab myself by the throat to get back on the phone and try again. And what d’ya know – he picked up almost straight away and talked to me for an hour and a half.

I spent every free day trying to search out people to interview for the book. The scene was close knit enough that each person would pass me onto the next one. I’ll always remember the long interview I did in the backyard of Phil Fuemana’s house, which was briefly interrupted by Dei Hamo stopping by to pick something up. Or sitting on the porch at DLT’s house and him looking up at a tui in the trees and saying “we’re talking about history so the ancestors have come to check us out.”

It took endless phone calls to Sir-vere before he finally found time to talk, though he was always nice about telling me to keep trying and later had me on his TV show to promote the book. I also attended the shooting of Scribe’s video for ‘Stand Up’ (after hearing him mention it during his support slot for De La Soul), but foolishly didn’t even bring my camera along with me.

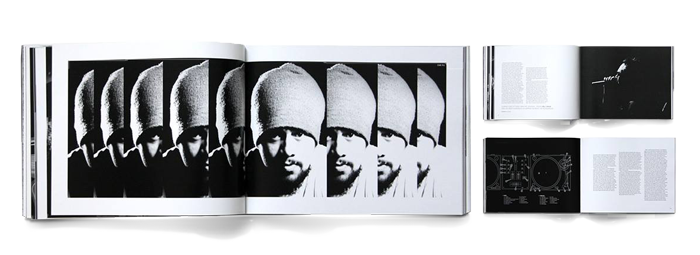

Some of many interior graphics created by Steve Russell for Hip Hop Music In Aotearoa

I did miss a couple of people. Manuel Bundy would’ve no doubt added more to the picture and I was disappointed I couldn’t track down Che Fu – his CDs were the only ones apart from Bob Marley that I found would go down well on the stereo at the Auckland City Mission during the years that I volunteered there and you were equally likely to hear his music at a Ponsonby BBQ, so he was truly omnipresent for a while there. I rang Che’s manager so many times that he stopped taking my calls (if I tried phoning him from a different number, he’d suddenly pick up!).

One of my biggest strokes of luck was that the in-house designer I was assigned at Reed Publishing turned out to be Steve Russell. He was a hip hop fan and relished the chance to do the book (rather than endless gardening and cooking books!) so he worked long days to make sure it was perfect. He liked my grainy shots and made them a thematic element of the book, plus had the sharp eye to see how a pic of Devolo doing the fingers could be cut to make a striking book cover…

Devolo

The book launch was held at Real Groovy, but I was horrified when Submariner came up to me on the night and said I’d got something wrong about him (someone had told me he’d started out in techno and I hadn’t checked my facts – I sorted things with him later, but that mistake horrified me at the time). The book even received a nomination at the national book awards and I flew down to Wellington for the ceremony. It won and I stayed up for a couple of hours afterward drinking with Steve Russell in my room – something I regretted the next morning when I was woken early to drive out to Avalon for an TV interview on the Good Morning show.

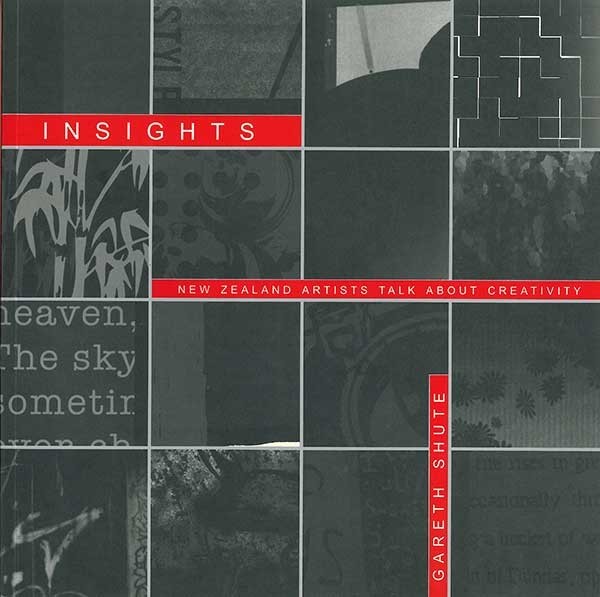

I turned up at work the next week to find that my fellow staff had put up a “congratulations” sign with balloons. It was unfortunate timing since I’d already decided to quit work and become a freelance writer. I figured I’d be a shoo-in for funding and would then be able to swan down to Wellington each year to pick up another award. How deluded! I never did manage to get funding for any of my books and Reed Publishing hadn’t even picked up my next project (a guide for local musicians: Making Music In New Zealand, 2005) so instead I signed with Random House and did two further books with them: Insights: New Zealand artists talk about creativity (2006) and NZ Rock 1987–2007 (2008).

Book design by Simon Amos

Cover design by Katy Yiakmis, interior design by Simon Amos, research assistance from Tosh Ahkit

I did attend the book awards one more time – on behalf of Elliot “Askew One” O’Donnell’s book, Inform: New Zealand graffiti artists discuss their work (2007), which I’d written a few chapters for. Though when the MC described the nominees for reviewer of the year, it turned out that one of them gained their place partially for an extremely harsh review of my book, Insights. I felt like standing up and saying – “I’m here, you realise?”

Sunday Magazine, 22 October 2006

I ended up a little burnt out after writing four books in the space of five years and taking part in three overseas tours (with The Ruby Suns and The Brunettes) during the same period, as well as helping Scott Mannion and Jonathan Bree with their record label (Lil Chief Records). I went back to the girlfriend I’d had before I wrote any books or played in any bands (Mieko Edwards) and finally took my foot off the gas. I did self-release another book, Concept Albums, a few years later but mostly directed it to an overseas audience.

Gareth Shute (foreground) and Mark Stebben playing in The Ruby Suns - photo by Ian Jorgensen/Blink

Gareth Shute playing valve trombone for The Brunettes in London, 2008

Cover design by Baly Gaudin

These days you’ll still find me playing shows as guitarist/singer of Fever Party and writing pieces for AudioCulture. And I heard from Steve Russell the other day that he’s in the UK and has worked on a run of high profile books covering the record labels, Motown, Blue Note, and Verve. He’s currently working on a book called Hip Hop Raised Me by UK hip hop legend, DJ Semtex, which has seen Steve handling contact sheets of previously unpublished images of Nas, Biggie, Wu Tang, Public Enemy, and NWA.

I did return to Auckland Libraries for a while and occasionally saw Hip Hop Music In Aotearoa on the library shelves as I walked to my desk, and got a kick out of seeing it there. It was an amazing moment in time and I’m just glad I was there to record it.

–

Gareth has played with (amongst others) The Tokey Tones, The Ruby Suns, The Broken Heartbreakers, Dictaphone Blues, The Cosbys, The Brunettes, and The Conjurors.