Flatmates spinning singles, Wellington, 1961. From left: Lybia Huata, Allies Ormsby, and Aroha Te Aho. - photograph John Ashton, Alexander Turnbull Library, JA-6140-04-F.

In the early 1970s, my after-school journey from Onslow College would conclude with a walk from the Wellington Railway Station, through the heartland of the civil service to the bottom of Lambton Quay, where I would catch the Cable Car home to Kelburn.

Along the way I would pass at least half a dozen places that sold records. I could not afford to buy any, but just by hanging around these shops I’d get to hear new music that would otherwise have remained an alluring cover on the shop wall or a tantalising review in Sounds, Melody Maker or NME.

The department stores – Haywrights, McKenzies, Kirkcaldies, the D.I.C. – all had record sections of which Kirks’ was the most salubrious. It had a listening room with hi-fi speakers and comfy chairs and sometimes half a dozen of us in our school uniforms would crowd in and splay ourselves and schoolbags about the furniture and floor. The turntable would be operated from behind the counter by a middle-aged sales assistant. If they were kind or distracted, this person would allow us to hear a whole side of an album uninterrupted. Other times they would annoyingly lift the stylus part way through a song before appearing around the door to ask whether or not we would be buying the record. This was the signal that our time was up, and we would move on to the next location.

Digging for discs at the James Smith’s record centre, Wellington, 1960. - Dominion Post negatives, Alexander Turnbull Library, EP/1960/1515-F.

The D.I.C. also let you hear records, on headphones positioned at listening stations. While the assistants, like the majority of the customers, were women in their fifties or older, I sometimes found product in their record bins clearly not intended for the dominant demographic. It was here I first encountered An Evening with Wild Man Fischer. The cover shows the demented-looking Fischer, a former psychiatric patient, with his arms around a woman who is supposedly his mother, though she reminded me a bit of one of the D.I.C. sales team. I listened. It may be the most disturbing record I’ve ever heard.

Bag from the Record Centre in the D.I.C. department store, Wellington. - Chauncy Ardell collection

The D.I.C. also housed a booking agency, where we would queue up to buy tickets for visiting acts such as John Mayall or Chuck Berry.

But the most congenial stop was The Record Specialists. It was a small narrow store selling nothing but records. It had an aisle of LPs on either side and another down the middle for singles, which left little space for movement. If you wanted to sample something you had to persuade the assistant to play it over the shop speakers. For a while, this was a tall, longhaired, lugubrious-looking bloke in his early twenties whose name I learned was Bill.

Record Specialists sticker. - Adam Miller collection, 78rpm.net.nz

Bill’s snorts and grunts made it clear he didn’t think much of my requests. Once when I asked him to play a record – I think it was by Frank Zappa – he flatly refused and instead put on a new album that had just come into the store that day. It was David Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust, which he told me categorically was “going to change everything”. Another time he played me Lou Reed’s Berlin, which I found almost as troubling as Wild Man Fischer.

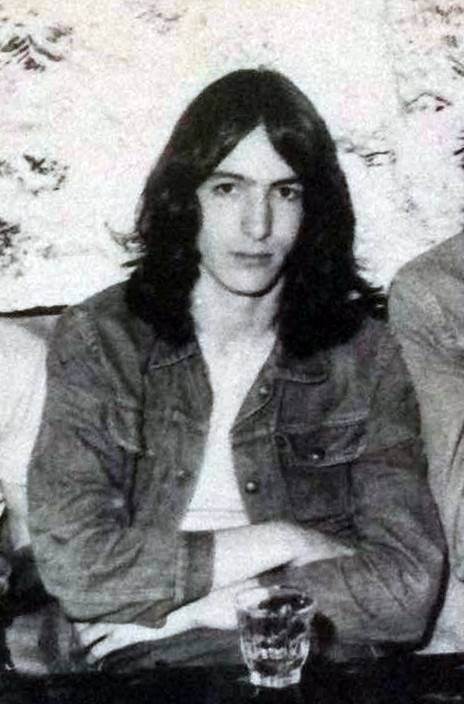

Bill Payne, music evangelist at The Record Specialists, early 1970s. - Jackson Payne

He didn’t seem to mind that I never bought anything. He tolerated my pennilessness and, in his sardonic way, seemed to show his approval of my music obsession, if not my tastes. He would even lend me things – brand new unopened discs straight off the shop shelves – with the instruction to return after the weekend and to be careful not to spill beer on them as he had to sell them as new.

Many years later Bill Payne would become known as a writer. A strong musical current runs through his collection of short stories, Poor Behaviour. With its cast of deviants and misfits, the book reads a little like a literary version of Ziggy Stardust and Berlin, relocated in early 70s New Zealand.

On Friday nights, usually with a few friends in tow, I’d extend my journey all the way to Courtenay Place, passing another half-dozen or so record shops on the way. In Manners St was Lamphouse, where my record mania had begun a decade or so earlier.

When I was five, my older cousins had played me some of their Beatles records and I was instantly hooked. Give me more, hey hey hey, give me more! I pestered my mother until she bought me my own Beatles single. When she told me she had got it at the Lamphouse, I imagined a lighthouse, somewhere in Wellington harbour. So that was where records came from. It seemed plausible enough to me as a five-year-old.

If you want to give pleasure, give records: advertisement, 1966 - Bruce Anderson papers, Alexander Turnbull Library.

While I soon learned the more mundane truth, Lamphouse did remain a kind of beacon for me. The all-purpose electrical goods store also included an excellent selection of records. Of special interest to me was the deep sale bin, brimful of 45s by lesser-known artists or flops by better-known ones. I’d never find any of my beloved Beatles in there however hard I looked, but at one shilling each these were all my pocket money could buy.

On a Friday night when the shops were open late Mum would drop me off at Lamphouse while she went to do the shopping. An assistant would bring a stepladder from somewhere out the back so I could climb up and reach the bin which I would trawl dreamily for an hour, holding up the seven-inch singles and teaching myself to read by studying the song titles, artists’ names, brands and even serial numbers on the labels. I’d begin to make educated guesses as to which records I might like. My finds were obscure but satisfying and many of those singles remain lifelong favourites: ‘Dragster On The Prowl’ by The Dovells, ‘I Shot Mr Lee’ by The Bobbettes, ‘Four Letter Man’ by Freddy Cannon, among others.

Al Martino, Neil Diamond, Perry Como, and 'Band on the Run': Lamphouse advertisement, Evening Post, 6 May 1974. - Bruce Anderson papers, Alexander Turnbull Library.

Lamphouse was still there when I was making my after-college vinyl crawls in the early 70s, but my schoolmates and I were more likely to wind up at Vanvi’s in Cuba Street, which, like James Smiths, had a listening room.

A few years later I was living in a flat of dissolute teenagers just off The Terrace, within walking distance of most of the record shops in Wellington. Now that I was earning some money, I began to build my collection. Older records I would usually find at Silvio’s secondhand shop on Willis St, though one could also sometimes get brand new recent releases there at cheap prices, flicked off by reviewers or record company reps. If I couldn’t find what I was looking for at Silvio’s, I’d usually head to Colin Morris’s on The Terrace. With my frequent visits, Colin, Silvio and their staff members would get to know me and I’d often end up in conversation with them about music.

Though there are far fewer record shops today than there were in the seventies, or even a decade ago, I still find it hard to walk through Wellington without stopping in at the handful that currently exist. I still like to talk to the people that work there and sometimes ask them to play something I want to listen to, and sometimes they will tell me that they have something much better that I need to hear.

--

Read: Wellington’s Early Record Stores

Read: Wellington’s Lost Record Stores 1 – the Golden Mile

Read: Wellington’s Lost Record Stores 2 – burbs and back alleys

Read: Silvio’s – the accidental record store

Read: Colin Morris

--

Thanks to Colin Morris, Dennis O’Brien, and Kevin Kane