On the face of it, John O’Shea – the director of Don't Let It Get You – was an unlikely auteur. A shy, stuttering Irishman with no formal training, his prime motivation was to challenge the popular view of New Zealand as a “Decent Society”, particularly as represented by the Government-funded official media institutions, the National Film Unit and the NZBC. Historian O’Shea’s outrage was particularly focused on the romantic, inaccurate and often downright erroneous portrayal of Māori, who were still represented anthropologically in NFU documentaries and virtually absent from television coverage.

As a young man, O’Shea had studied law, history and arts at Victoria University before serving in World War II on the Italian Campaign. Back home and married with two children to the indefatigable Cormie, he was working as an historian at the War History Branch in 1948 when, inspired by the European art-house films he and NFU alumni Roger Mirams were screening at the Wellington Film Society, they decided to abandon all reason and set up a film studio in a shabby industrial building in the bleak and wind-swept suburb of Kilbirnie.

During the filming of John O'Shea's 1964 feature Runaway, focus puller Michael Seresin (left) and cameraman Tony Williams line up a shot featuring actress Doraine Green - Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision

Fortunately, it was passion, not profit that fueled their determination. With no government funding for independent film production and no outside commissions from the state broadcaster, Pacific Films initially survived by producing low-budget training films and educational documentaries.

Broken Barrier (1952)

Evidence of O’Shea’s vision and risk-taking is shown by his decision in 1952 to embark on his first feature film. Lacking experience in writing and technical production, he persuaded cameraman Mirams to collaborate on the script of Broken Barrier, a myth-busting view of contemporary race relations during the assimilation period. It told the story of an interracial couple, played by local stage actors Kay Ngarimu and Terence Bayler, in their struggle to find acceptance not just within the wider culture but their own families. The challenge of making a feature film in New Zealand in 1952 proved almost impossible. There were no crews or actors with dramatic film experience. There was no budget. Outside the closely guarded facilities at the National Film Unit there was hardly any suitable equipment.

But O’Shea was unstoppable. He persuaded Mirams to borrow two cameras: one mute 35mm Arriflex from Movietone and the other liberated from the Germans during World War II. They constructed their grip equipment and lights from scrap materials. The entire production was run out of Mirams’s Vauxhall car.

Working from nothing, the filmmakers had to rely on their wits. The entire crew was friends who worked for nothing. With no access to synchronised sound, O’Shea replaced natural dialogue with “stream of consciousness” voiceovers recorded in post-production. In a sign of things to come, they were refused permission to use the Film Unit lab to process their stock because they were considered to be “private enterprise”. Luckily, Mirams managed to persuade his other employer, Sydney-based Movietone News to help them out with editing and negative-matching. Finally, they raised enough money to record a score and add sound effects in Sydney.

Broken Barrier was not a financial success but fortunately it did not sink the company. Mirams and O’Shea survived through part-time jobs: Mirams shooting footage for Movietone News, and O’Shea moonlighting for the Government Film Censor.

Runaway (1964)

In 1956 Roger Mirams moved to Sydney, where Movietone was based – but O’Shea refused to give up his feature film dreams. He spent the next 12 years raising the finance for his next project. This was Runaway, considerably more ambitious than his first feature and conceived as a scathing critique of conventional New Zealand society. Runaway is the story of pleasure-seeking David Manning (Colin Broadley), who leaves his straight life behind him and sets out to discover the “authentic” New Zealand. To enhance its themes of existential alienation, casual sex, the quest for freedom and absurd twists of fate, O’Shea added some more populist elements from the thriller and the American road movie. It also borrowed heavily from New Wave European films.

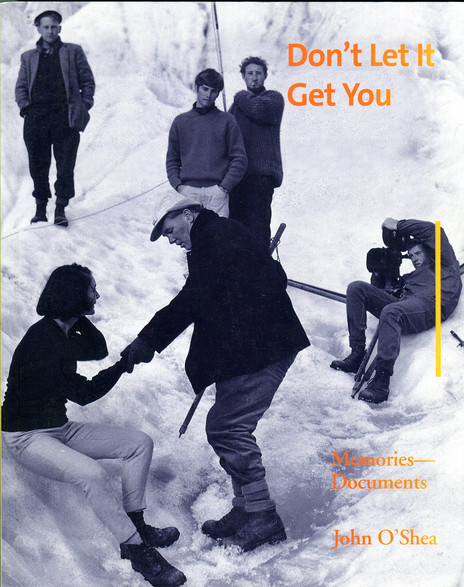

In this production still from Runaway (1964) John O'Shea, centre, directs Deirdre McCarron on location at Franz Josef Glacier; the cameraman is Tony Williams. In the background, from left, are recordist Ron Skelley, camera assistant Michael Seresin and actor Barry Crump. The image was used on the cover of John O'Shea's posthumous Don't Let It Get You: Memories-Documents (VUP).

On the run from the police, Manning travels the length of the North Island, crosses Cook Strait on the ferry and by the final credits is walking into the foothills of the Southern Alps. Along the way he has relationships with three different women. The first is Laura (Nadja Regin), a European sex kitten driving a stylish American convertible through the Hokianga. Next is innocent “Māori Maiden” Isobel (a very young Kiri Te Kanawa) and finally a sophisticated older woman, Diana (Deidre McCarron). The part of a lecherous pig hunter is convincingly played by Barry Crump. The muddled results left audiences largely bewildered.

What O’Shea lacked in support from the film and television community, however, was compensated by his close relationship with the members of the Wellington literary and arts scene. These connections proved to be the impetus for O’Shea deciding that his next project would be a musical. When he engaged 21-year-old, first-time cameraman Tony Williams – the son of a station manager for the NZBC and later the manager of the National Opera Company – to shoot Runaway it was on the evidence of his first experimental film The Sound of Seeing, which had been a collaboration between Williams and talented young Wellington composer Robin Maconie. O’Shea subsequently commissioned Maconie to write the original score for Runaway, which was snail-mailed to Kilbirnie as by then Maconie was studying on a QE2 Arts Council grant in Vienna. It was recorded at the NZBC studios with members of the NZ Symphony Orchestra under the direction of 27-year old conductor Patrick Flynn. Flynn also composed the opening and closing music for the film, performed by an 18-piece jazz band, while the organ parts were played by Brian Findlay on the Auckland Town Hall organ.

‘Runaway’ musician Patrick Flynn was perfect for the crew’s gang of bohemian rebels.

Bold and talented, Flynn was a perfect addition to O’Shea’s gang of bohemian rebel creatives. He had originally joined the Royal Marines as a boy bandsman at the age of 14 and transferred to the Royal NZ Navy in 1959, becoming one of the first members of the Royal NZ Naval Band in 1962. As well as his official duties, he went on to perform in “shore-side” classical and jazz concerts and formed the Symphonic Wind Players, whom he was rehearsing in the Auckland Town Hall on 25 April 1964 for an upcoming concert when he was abruptly arrested and hauled away by the Military Police. Subsequently, Flynn was sentenced to 42 days detention and reduced to the rank of “musician” for deserting from his “ship”, the land-based HMNZS Philomel, aka the Devonport Naval Base. A perfect resume for joining the Pacific Films staff.

Similarly, William’s camera assistant on Runaway was a very young and inexperienced Michael Seresin, son of Harry, a prime mover of the beat poetry and music scene in Wellington. Along with Peter Bland, Tim Elliott and Martyn Sanderson, Harry Seresin was a co-founder of Wellington’s Downstage Theatre and ran a lively salon for Wellington’s bohemia in his Settlement cafe on Willis Street.

The novelty of all this cannot be underestimated. This was in the days before film was considered one of the “creative industries”, before film subsidies and the advent of film schools. When Williams told his school vocational advisor that he wanted a career in the arts: “I said ‘Maybe film’. They looked at me strangely and they said, ‘Film? What do you mean by film?’ And I said: ‘Well, you know, film ...’ They looked at me blankly ... Anyway they came back and said: ‘Well, we’ve got an opportunity and a possibility – we think you should be a hairdresser!’ ”

Seresin recalls the environment at Pacific in the mid-1960s as being a new and different world: “They were cosmopolitan people who’d either been born abroad or travelled and were sympathetic to food, wine, ideas – discussing abstract things instead of the rugby score or the price of two-toothed sheep… We imagined we were pretty avant-garde.”

Williams: “John was giving us a film education. We used to drag projectors home. Cormie would make coffee and home-made bread and we would watch Orphée, the famous one by Jean Cocteau. We would watch these endlessly, weekend after weekend, then we’d go to the Monde Marie and sing folk songs.”

Rather than be silenced by his critics, John O’Shea went on to greater heights.

Rather than be silenced by his critics, through the 1970s and 80s John O’Shea went on to greater heights, producing a stream of documentaries and dramatic films that would continue to challenge the social toll of New Zealand’s escalating consumerism and the myth of its racial harmony. Pacific Films continued to be a Mecca for a floating population of filmmakers, actors, musicians, artists and rebels and in its prime, with a payroll of up to 30, it was a film school in everything but name.

Despite the fact that O’Shea was a generation older than most of his staff, he and his loyal henchmen Eric Anderson and Craig “Crunch” Walters continued to provide generous support and inspiration for a roll-call of New Zealand’s most successful film-makers. Among them were directors Tony Williams, Barry Barclay, Aileen O’Sullivan, John Reid, Michael Black and Owen Hughes and Gaylene Preston, writers Michael King and Michael Heath, editors Ian John, Rick Spurway and Dell King; cinematographers Michael Seresin, Graeme Cowley, Keith Hawke, Mike Hardcastle, Rory O’Shea, John Blick, Waka Attewell and Alun Bollinger, sound engineers John van der Veerden and Craig McCloud; first assistant director Steve Locker-Lampson and production manager Sue May. On the periphery were Dick and Edith Campion and their daughters Jane and Anna, various members of BLERTA and a passing parade of actors, musicians, artists and intellectuals who contributed to Pacific’s eclectic range of productions.

If O’Shea had one fault it was his inability to reconcile the inherent contradiction in his roles as both idealist and company director. Williams remembers: “John was a lousy businessman because he spent all the profits fostering too many people.” Waka Attewell remembers: “Whatever we were shooting, there was the passion. We used to load the Kombi van and drive off into the tundra – and not come back until the documentary was in the can or Eric said we’d run out of money.” Yet his sensibility drove the company and he became a conscience for the industry for over 40 years. O’Shea’s views about a national cinema were well known: “If you don’t have a film from Iceland, maybe people will forget Iceland exists, and New Zealand is in about the same category”.

--