Starting out

Trevor Thwaites’ musical education began on the gig-rich streets of central-city Auckland in the early 1960s.

“There was a lot of music in town. When I started working at the Government Tourist Bureau in Queen Street you could catch live jazz at lunchtime. Drummers Lew Mercer and Mauri Fears and others had trios that played from 12 till 2pm, two consecutive lunch-hour sets. The Bali Hai was a good club on O’Connell Street, as was the Paris Boulevard in the remodelled Lewis Eady Theatre off Queen Street, and the Top 20 on Durham Lane. People would come and have lunch and a dance.

“Another interesting place in town was The Loft, a record shop halfway up Vulcan Lane. You had to climb up flights of stairs, they had these little listening rooms that would sit four or five of you. You could have your lunch there and they would play you the LP you’d selected. You inevitably bought it. It was a really good way to spend your lunchtime, keeping up with the latest things coming in.

“Some friends and I, in our late teens, would pass by Sydney Eady’s on Queen Street on our lunch break, and one day we decided we’d all get instruments. So I got the drums, and there was saxophone, bass and guitar. But music wasn’t an option at school. Later on when I was already playing I found some teachers, but it didn’t happen at school. All we seemed to do was sing a song for assembly back then.

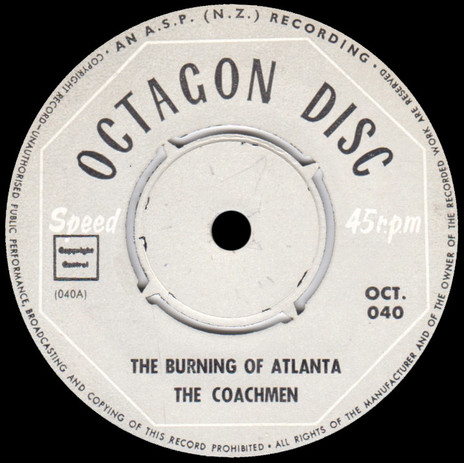

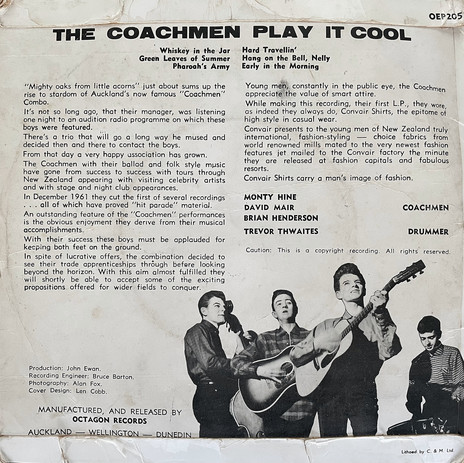

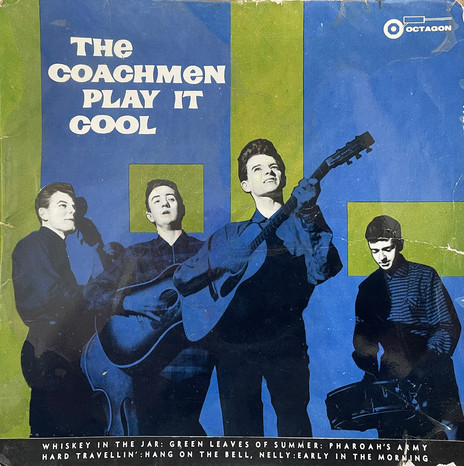

“I joined up with a folk trio called The Coachmen, who were doing shows around town. As well as playing drums I contributed to their comedy routines. We’d often be doing about five floor shows on Saturday, we’d start at Waiwera and do a couple of spots, then off to Waiatarua at the top of the Waitakere Ranges, to the Dutch Kiwi Inn where we’d do a dine and dance, three songs a set – a waltz, a foxtrot and a quickstep with the odd cha-cha slotted in (pre-bossa nova Latin style). Then into town for a show at the Orange Coronation Ballroom, then maybe The Montmartre afterwards. A pretty solid Saturday night! I might take a snare drum and a hi-hat cymbal to these gigs, not a full kit.”

Music theory

“When I started learning drums it was really hard to find a drum teacher. There was some resistance; no one wanted to teach the younger guys in case they got too good and took all the best jobs, but I did find a guy who could teach me the brushes. I started to buy records and listen to a lot of stuff, and just pick up things off the people you’re playing with. So I was mostly self-taught and had the key drum texts – Stick Control, Accents and Rebounds, Syncopation, Buddy Rich Snare Drum Rudiments and Jim Chapin’s Advanced Techniques.

“you’d have headphones on listening to shortwave radio, laying down the drum part”

“We were also doing some recording. I’d do sessions in the early days with Bruce Barton who had Mascot on the fifth or sixth floor of the ASB Building on the corner of Wellesley and Queen Street. Reverb and electronics were just coming in, but they weren’t ubiquitous as yet. So Bruce would have the violinist at the bottom of the lift shaft; the toilets were the vocal booth because they had those hard-tiled surfaces.

“We’d be doing versions of songs that were released in Australia but yet to make it across the Tasman, so you’d have headphones on listening in to shows on shortwave radio and laying down the drum part as the songs played. They were quite interesting times. We put together a Shadows-style band that Bruce called The Fenders with Peter Posa and Gray Bartlett, and did a record called ‘Toy Balloons’.”

Overseas

The thriving scene took a hit in the early 60s when a conservative Auckland Council decided there couldn’t be any live music on the Sabbath, which meant on Saturday you weren’t allowed to play after midnight.

“The guitarist Terence Cox and I decided that was no fun, so we got on a boat and five weeks later were in London. We shared a cabin with a young chap on his way back to Holland from Australia. Soon after we arrived in London he got in touch and said, ‘I want to buy some vibes, will you be my guarantor?’ And I said yeah … a week later he said ‘I’m going back to Holland, you can have them’. Premier vibes. Being his guarantor and his default meant they cost me about 150 pounds at the time. Rangitoto College have borrowed them at the moment. Later on I bought the Gary Burton Musser touring model, which had so many cases for each component. The Premier just folds down into its basic frame and you chuck it on the back seat and off you go.

Czechoslovakia in 1964 was under Russian control, “all very James Bond”

“So we landed in London in August 1963, just around the time The Beatles were breaking, and then the [Rolling] Stones. It was a great time. I spent four years playing in London and doing a lot of stuff on the continent. I was in a group, The London City Swingtet, that went to play in Czechoslovakia in 64, the first ‘western’ group to play there after the war. It was under Russian control, and all very James Bond. We were there for three or four months but at the end we found we couldn’t take the money earned, or what was left of it, out of the country. So we spent it on trivia.

“In 67 or 68 I was on the way back to New Zealand with my fiancee, and we spent about eight months in New York with her friends. I met Joan while I was working as an operating theatre technician at the Whittington Hospital in Highgate, she was an operating theatre sister. Her father was Scottish and her mother Mexican, they were out of Belize, so they had a lot of Latino contacts. It was very hard to pick up music work in New York with the very tight union situation. Musicians from other cities or countries had to wait quite a long time.

“One night a young Latino drummer and I went to see a Cannonball Adderley show at the Apollo Theatre. It kicked off with a movie starring [singer] Johnny Nash, then he came out with a big band and did a few songs, then there was a vocal group similar to the Four Freshmen, then a set from Eddie Palmieri the Latin-jazz player, followed by a flautist with a belly dancer … and then the Cannonball Adderley Quintet! All in all about four and a half hours for only two dollars. I think I was the only white guy there. So it’s late when we left and we walked down through Harlem, got home and everyone was, ‘You’re safe! There’s been riots in town!’ The whole time we were in the Apollo there had been riots raging outside, we were totally oblivious.” [The 1967 New York City riot began after an off-duty police officer shot and killed a Puerto Rican man named Renaldo Rodriquez who he claimed was carrying a knife.]

Teaching

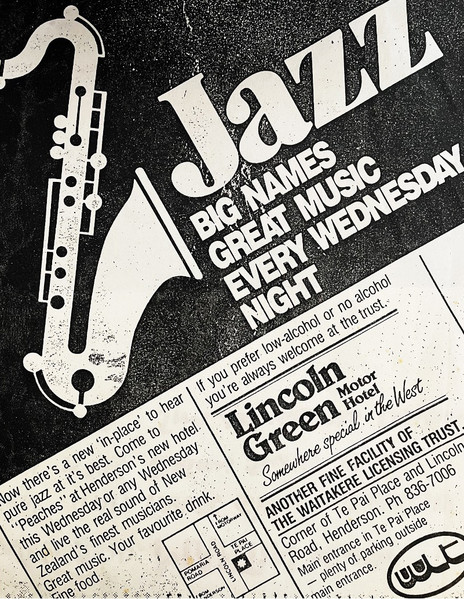

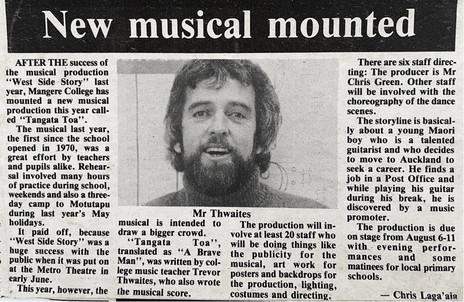

“So I came back to New Zealand, and while holding down an assistant position at a travel agent I found a good gig at the Mon Desir [Takapuna], Monday to Saturday, and a monthly show at the Yugoslav Club, up on Karangahape Road in a building that was previously a cinema, where the Sheraton [now the Cordis Hotel] is now. I did a music theory course at Auckland Technical Institute on Saturday mornings, a very good course which gave me Trinity College grades, and took some piano lessons from a man called Henry Shirley in Upper Queen Street, and I had another great piano teacher named Judith in Kohimarama. Then I enrolled at university and started a music degree, purely because I wanted to learn more about music. When I finished that I thought, well, what do you do with a music degree? I had no idea, but I thought teaching sounded like a good bet so I went to Teacher’s College and started teaching in 75 at Mangere College.

“Music in schools was just starting to broaden out and look at popular music, so working at Mangere with all the South Pacific and Māori students was great because you’d have gospel choirs, and they were listening to George Benson and Santana, it was a great time. Several students went on to make names for themselves: The 3 T’s, Jay Laga’aia, Betty-Anne Hall (Ardijah). The students just wanted to perform. I stayed at Mangere for 12 years. I was playing three nights a week at a hotel in the Downtowner Bar, nicknamed ‘The Snakepit’, in a basement on the corner of Customs and Queen Street, and I’d come to school having nearly lost my voice from all the second-hand smoke.”

“some lads came over from Western Springs and formed The Lowdown Dirty Blues Band”

In 1986, Trevor moved to Selwyn College. “That was a totally different kind of school. They wore mufti rather than uniforms, and the seventh form was twice as big as the third form because students came from Auckland Grammar, Waiheke and others. And I had great students, people like Otis Frizzell and Mark Williams, and some lads came over from Western Springs and formed The Lowdown Dirty Blues Band: Karl Steven and Ben Sciascia, along with Tim Stewart. Nick Atkinson was already at Selwyn. I was in a band with Jim Langabeer [a legendary jazz multi-instrumentalist who also taught at Selwyn College] called Superbrew which was an afro-jazz band. We had four saxes, I was on percussion and vibes. We played at school a few times, and the boys loved the music but liked the name even more and ended up calling themselves Supergroove.

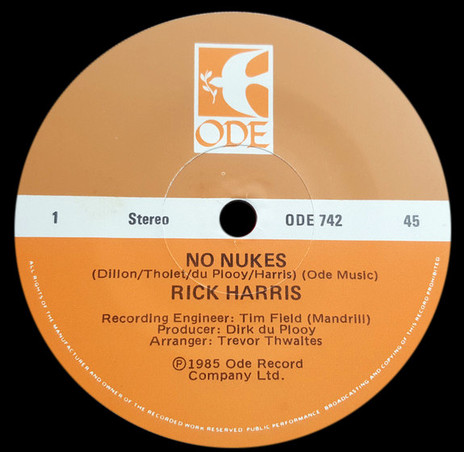

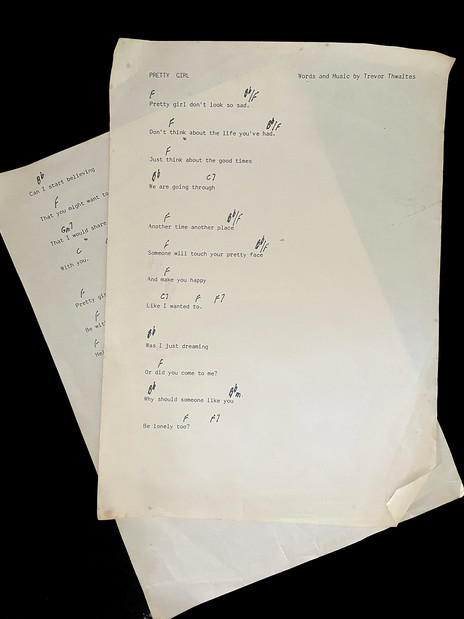

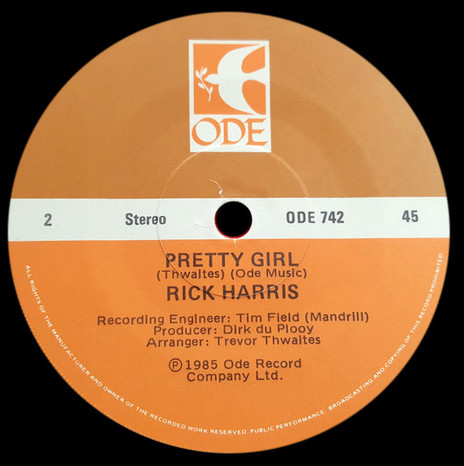

“I’d written a song called ‘Pretty Girl’, it was the B-side to an anti-nuclear tune. We’d given all the copies to the Rainbow Warrior guys to distribute, but they all went down with the ship when the French secret service blew it up. We did release ‘Pretty Girl’. Years later at Selwyn, Kirsten Morrell (Goldenhorse) sang arrangements of the song at school, and later told me it influenced some of her writing, although I don’t think she realised I had written it.”

One summer’s day in 1991, Trevor took his music class to watch New Orleans brass band The Dirty Dozen march down Queen Street. The jubilant sounds and rhythm were all too much and students found themselves swept off their feet and marching downtown alongside the band.

“Afterwards the boys found some brass instruments in the back room that weren’t being used, they pulled them out and got a pretty good sound out of them, almost like a dixie band! Those guys were so inquisitive,” says Trevor. You can still hear echoes of that day in Nick Atkinson and Tim Stewart’s Hopetoun Brown performances.

Trevor was keeping busy playing gigs with Jonathan McKeown-Green, a lecturer in the Philosophy Department at University of Auckland who he had met playing keyboards in a musical at Mangere College. The pair assembled a small analogue recording studio in a sleepout behind Trevor’s Pakuranga home.

“We called the studio Soundlink, and Chris Tate, who later had College Hill Sound, was like an apprentice engineer for John. We had an old telephone exchange board as a patch bay. John being unsighted, he could be a bit rough on the cables, so I spent quite a bit of time re-soldering them!

“I was a student at Takapuna Grammar,” says Chris Tate. “The music department at the time wasn’t up to much, but if you wanted to learn keyboards, Jonathan came in. He taught me how to make sounds on a synthesiser and play a few things. A band he played in with Trevor performed at Grammar and they were very, very good. I was obviously pretty enthusiastic about it all, and Trevor said, well, get in the van and come to Selwyn. So that’s where I met the boys who would become Supergroove, and by the time they were a proper band I was their sound guy. It was a completely organic process, which kinda sums up Trevor’s teaching style. Everything seems to be a series of happy accidents and you’re never really sure if he has orchestrated things or just created the environment for the good things to happen in.”

Singer-songwriter Caitlin Smith, who is deeply involved in jazz in Aotearoa, says of her time at Selwyn, “Trevor was such a jazz cat, and he was always gently pushing me in that direction. But I was pretty punk at that point, and supremely disinterested in jazz. It’s funny, but I still feel feral when it comes to jazz even though now I’m fluent in the language.”

“Trevor was such a jazz cat, always gently pushing me in that direction” – Caitlin Smith

In 1987 and 88 Trevor took students from his music programme at Selwyn to the Coromandel to spend a week at Aerial Railway Studio in Sandy Bay on the Coromandel Peninsula, where they learned the fundamentals of audio engineering and got some hands-on experience with mics, mixing desk and 8-track tape in a one-of-a-kind studio environment. “After the school trips there John and I went back and did some tracks for an Australian competition. Jane Horder joined us and got an award for hers when she’d only come down to do backing vocals on ours!”

Trevor became involved with music at Mercury Theatre for the last six years of its existence, playing in orchestras as well as producing sound effects for various productions at Soundlink. These included a blowfly for the Mercury production of Nana, and the sounds of an elephant’s stomach for the Auckland Zoo.

“What killed the Mercury was the production of Carousel, the musical,” says Trevor. “Beautifully produced, Brent Brodie in the lead who did a great job, but the show just didn’t get enough people through the doors. I think the story might have been a little dark. Fiddler On The Roof and South Pacific would be getting 96% houses, Carousel only did about 50% …

“But it was fascinating being part of those productions, the person writing the arrangements would be at dress rehearsals making changes right up to the last minute, handing you new material just before you went on. I played with the APO on and off as well; doing Turandot at the Mercury was great. A most expressive piece of music for the percussionist as opposed to lots of classical where you send most of your time counting, and waiting or your cue.”

In 1992 Trevor was invited to apply for a Senior Lecturer position at the Auckland College of Education. In 1995 he became principal lecturer, and that same year became the chairperson of the Music Advisory Group developing unit standards for the NZQA.

“The Music Advisory Group had a big meeting in Wellington which was the beginnings of the NCEA. That was fascinating because the unit standards at that point were just pass/fail. The group brought people together from recording and sound, but there was a lot of resistance to introducing performance. Fraser Tāhau and Tama Huata had a background in showbands and the like, they developed a unit standard on group performance and ensemble playing where there was more emphasis on attitude and being a team player, less about being a star. It’s answering the question ‘what is group playing compared to solo performance?’. So I was quite disappointed when they were disregarded given the knowledge that went into their input. The new advisory group for NCEA had some great people involved, but they were all teachers and the project missed the opportunity to have that aspect of the industry and tangata whenua represented.”

While developing the unit standards, Trevor became aware of the work Rim D. Paul (original member of the Quin Tikis and founder of the National Māori Choir) was doing with Te Runanganui O Te Arawa and his own organisation The Māori (Te Arawa) Music Academy. Rim had been developing the concept of a curriculum for Māori music based on indigenous worldview and spirituality, and was looking for input on how it might align with existing academic structures. Rim and Trevor connected at this critical period in the realignment of music education in schools, and continue to collaborate on this work today.

“There was no such thing as Māori music as an academic practice” – Rim D. Paul

“As chair of the Advisory Committee, Trevor was already investigating how the Māori perspective would fit in with the unit standards,” says Rim. “There was no such thing as Māori music as an academic practice, and my background is more what you’d call ‘the school of a thousand one-night stands’. But Trevor was able to frame my thinking from his perspective, assuring me right from the start that what I was proposing was completely valid from an academic viewpoint. We continue to have those conversations, leading to realisations that bring it all together.”

In 1998, the year he finished his Master of Education degree, Trevor became Project Director for Music for the Arts In New Zealand Curriculum. His continued involvement enabled the project team at Auckland College of Education to draw on what was happening in the unit standards by including a strand that was about performance, and a strand about composition.

“That became official in 2000. At the same time they started developing Achievement Standards, which were evaluated as Achieved, Merit, Excellence or Not Achieved, finally dispensing with the old pass/fail. But in 2006, the Ministry of Education decided to put all seven learning areas in the curriculum into one single document with limited pages and this meant that a lot of information for teachers suggesting how to teach the arts was lost, boiling it down to two pages. But they kept the strands from the 2000 document, so that was fine.”

In 1999 Trevor had begun publishing a quarterly magazine called Music Teach. “I put that out for about four or five years, but it was quite hard to get people to renew their subscriptions, they’d get in touch five years later saying ‘I haven’t had a Music Teach lately?’ but it was hard to keep going when it wasn’t paying its way. That was an endeavour to let music teachers know what was happening around developments in the curriculum.”

Trevor’s focus on aspects of literacy in music is reflected in his academic concerns as well as his practice. In 2005 he joined the University of Auckland as principal lecturer, and over the next 10 years would go on to become Head of School of Visual and Creative Arts and later was Deputy Head of the much larger School of Arts, Languages and Literacies.

“I’m interested in literacies in music, which is reflected in my PhD [Trevor’s doctoral thesis is titled Being Literate In the World: Music, language and discourse in education]. I don’t just mean reading music but literacy in it as an art form. My experience playing in orchestral stuff as well as in high schools and covers bands is all about the different ways diverse groups communicate. It can be pretty critical. When it comes to jazz, the conversation you have before you start playing is really important to how you relate to each other once you do. It’s such a challenge with the way things are looking as the arts are downgraded in education, I like to try and push back a bit.”

Mike Chunn approached Trevor with the idea to expand music in schools even further. Why not bring contemporary songwriting into the curriculum? In 2016 Chunn discussed the process in The Spinoff.

“In January 2015, I met with Trevor Thwaites, a cool drummer but also a senior lecturer at the School of Curriculum and Pedagogy, Faculty of Education, The University of Auckland. Trevor had been involved in much of the music curriculum achievement standard writing to date so we ordered a beer each and we got talking about songwriting. It didn’t take long before a plan was made.”

riding a wave of support, Songwriting became an NCEA subject in 2016

A steering committee put the plan through its paces, and riding a wave of support from industry, artists and teachers, Songwriting became an NCEA subject in 2016.

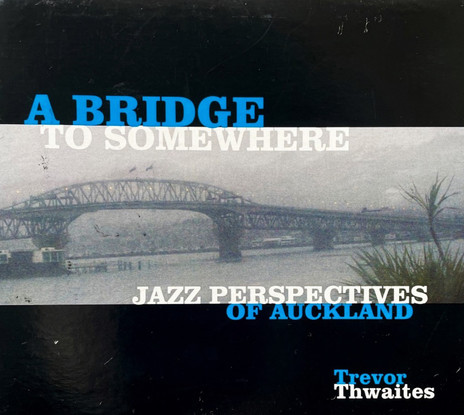

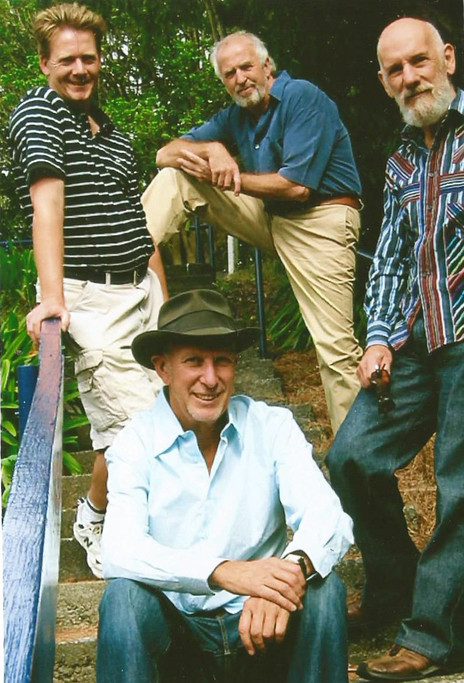

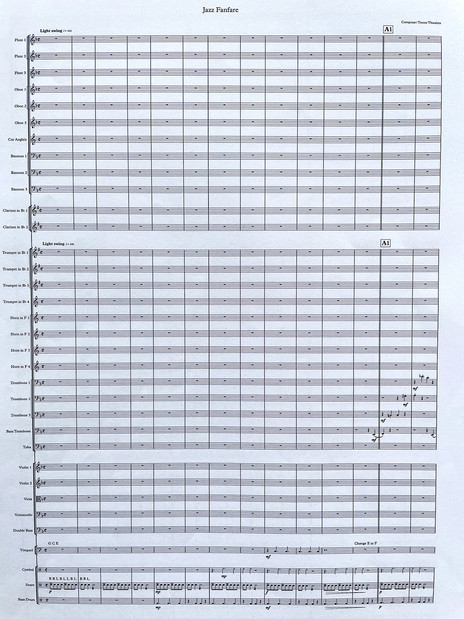

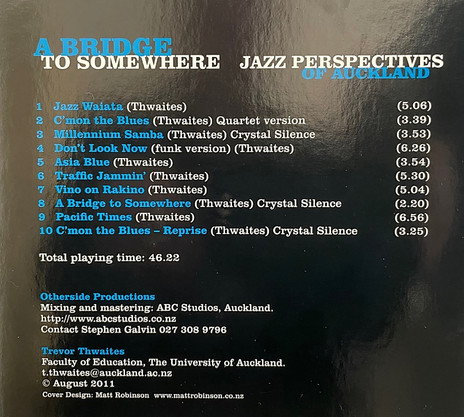

In 2012, Trevor had recorded an album titled A Bridge To Somewhere. “I wanted to make something a bit like the old Blue Note sessions where everything is done in the one take. Jim Langabeer, who passed away in 2022, is on some of the tracks. I pulled in various musicians, such as Bruce Morley’s Exit Band on the tune ‘Jazz Waiata’, and composed some music for it. I was playing mallets with Bruce at the time, he’s on the tune ‘Jazz Waiata’. I had just bought a lovely set of new Musser vibes to play in Bruce Morley's Little Big Band, but sadly Bruce passed away before the vibes arrived in New Zealand. The band was really great. He also played in my big band [The Prohibition Big Band, now part of the West City Concert Band] which has been going for 30 years. The band features a shifting roster of notable professional musicians and music teachers – who are often one and the same – alongside younger players from jazz school. It’s great to be associated with that vitality and the younger perspective, I love it.”

These values are also evident in Trevor’s involvement as chairperson of the KBB Music Festival (2009-2023). A yearly event established in 1983, KBB Music showcases secondary school orchestras, concert bands and jazz bands and surpasses even the Smokefree Rockquest in its longevity. It likewise offers awards and mentorship programmes to young aspiring musicians, with around 4500 participating annually. Administered by the Auckland Secondary Schools Music Festival Trust with KBB Music as its principal sponsor, one of its main aims is “To promote growth in instrumental music and encourage performance by all groups – novice or highly experienced.” A very Trevor ethos indeed.