As a group I think most of us shared a healthy scepticism towards life, but there was a palpable excitement at the prospect of Toy Love finally recording an album. The band was brimming with songs that they’d been playing live for months, and that deserved to be nailed down for posterity and wider circulation. Also, there had been precious little new material written so far in Sydney and there was a real desire to bear down on that aspect.

So I thought that recording the album might move things forward on several fronts. I don’t recall a lot about the day-to-day process itself, other than countless hours sitting in the control room behind Todd Hunter and Christo the engineer, playing pool, ducking out for food and drink, and treating it very much as an education.

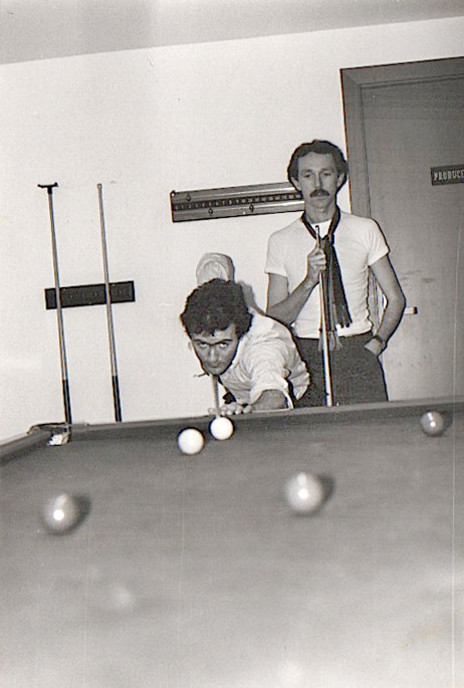

Playing pool at the EMI studios during recording for the album… Ian Dalziel potting. - Carol Tippet

I also don’t clearly recall how the initial connection was made that led to Todd Hunter working on the second single (‘Don’t Ask Me’/‘Sheep’) and later the album, although Chris Knox had a friend who once roadied for Dragon and maybe there’s a link there somewhere. Nobody quite remembers. Alec says that he’d not met Todd before and that it was Chris who had really pushed for his involvement. Of course Todd was and remains best known for his work with Dragon during their years of glory in the late-70s. He seemed genuinely smitten with Toy Love and later said that when he first saw them at the Gluepot they were “… fucking great. Great songs, huge energy.”

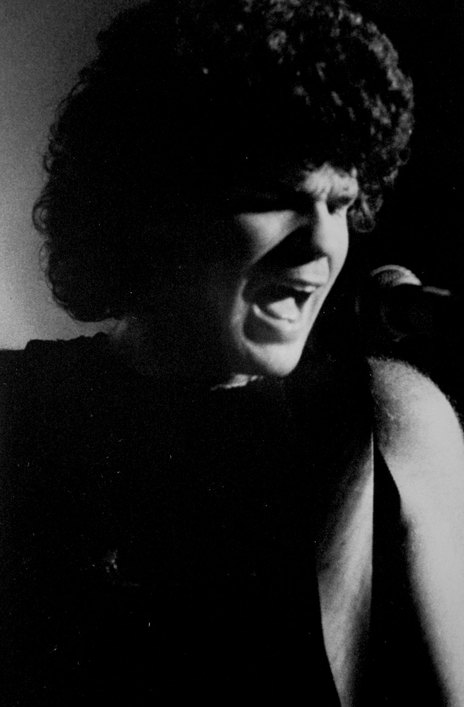

Todd Hunter in the mid-1970s - Photo by Larry Jordan. Richard Driver collection

Alec’s gear, which worked beautifully on stage when turned up loud, was considered problematic in the studio and wasn’t played above half volume, while Mike’s drum kit was discarded altogether. The band weren’t comfortable with the degree of physical separation insisted upon by the engineer and Mike in particular hated being isolated in a booth. As Chris has said, Toy Love had a complex, swirling type of sound. Paul didn’t follow Mike but played as a sort of rhythm section with Jane, and Mike followed Alec who followed Chris.

This was a challenging interaction to capture and the kind of separation that was standard for most studio recording wasn’t ideal for this lot. For some reason a long session trying to nail the intro to ‘Bedroom’ sticks in my mind as an example of how something that simply happened on stage, was difficult to reproduce in the studio.

Everyone admits to having been overawed to an extent, and submitting too easily to some of the demands. It was a steep learning curve, including some lessons in what not to do in the future. None of this, however, should detract from Todd’s obvious commitment to making an album worthy of the band. In lamenting the ultra-clean studio sound of the time, he told the NZ Herald in 2012 that “the band deserved an LP that was far more raw and anarchic” and that “we all tried our damnedest”.

Chris Knox with Toy Love, Sydney, June/July 1980 - Photo by Michael Green

The sessions were mostly in midnight shifts to take advantage of the cheaper studio time. Recording, overdubs and mixing stretched between June the 3rd and Todd’s birthday on the 21st. My impression was that everyone thought most things sounded fairly good on the studio monitors. A few days later there was some extra work done on ‘Good Old Joe’ and ‘Amputee Song’, destined for the B-side of the third single “Bride Of Frankenstein’, to give a couple of extra items not on the album. Accusatory and despairing, the themes are typically Toy Love, and I immediately liked both tracks. ‘Amputee Song’ dates from just before the band left Auckland, although I don’t remember it being played a lot, while ‘Good Old Joe’ was a rare Sydney composition. So they were relatively new, sounded taut and fresh, and in their own way held up strongly alongside the time-tested album tracks … a healthy sign.

However, one thing I already knew from my limited experience was that what you heard on the studio monitors didn’t accurately reflect what happened when the needle finally dropped onto vinyl. During this period of making the album I might have had my fingers crossed just a little bit. Of course the band members all had huge personal and creative stakes in this caper, but in a smaller way I too had something on the line.

Once the final album mixes were done, there were a few gigs to fulfil before the band went down to Melbourne. We had cassette copies of the tracks and I carried mine around with me, playing a track here and there for friends. It wasn’t easy to get a good sense of how it sounded away from the studio, hearing it on little cassette players and boom boxes, and never on a decent system of any sort for those first few days. There were such high expectations by so many people, including ourselves, that I recall feeling impatient for the album’s release so that whatever the reaction to it might be, everyone could just move on.

Toy Love: Mike Dooley, Paul Kean and Jane Walker in Sydney, early 1980 - Photo by Carol Tippet

At first, with only the studio cassettes to go by, there seemed to be a muted sense of satisfaction around the group, although “non-committal” might be more accurate. Arriving at the band house one day I noticed Chris lying on the floor of his room with headphones plugged into a cassette player, listening to the album. When he emerged I met his eye across the room: “Well it sounds like rock’n’roll”, he said.

Meanwhile there was the matter of a cover. Although Chris had told me that if it was down to him the album would be called Ceiling With Knives, there was no agreement on a title other than the band’s name. So Toy Love it would be. However, no cover artwork was forthcoming and nobody was volunteering as the days slipped by. I’d made a commitment to take a cover into Deluxe the week before the band headed south, and I was panicking just a little.

Deciding to do the back cover myself I chopped up bromides of some Philip Peacocke promo photos I’d held onto, along with an eyeball image from an op-shop magazine. In yet another late-night scramble of Letraset and spray glue the back cover artwork came together, full-size and pretty much as it looks, with a single overlaid instruction saying make the border yellow. It got the OK. By now, Mike was working on the poster insert and Chris on the inner sleeve with lyrics.

But still no takers for the front cover. I had something involving a frog that I’d put together earlier, but when I presented it Chris thought it looked too much like a Residents album. Jane came to the rescue. She and Paul shut themselves in their room on the Sunday and emerged late in the afternoon with Jane’s nicely nasty concoction of Indian ink and yellowy wash. When I took all the artwork over to the Deluxe office Michael Browning wasn’t there, so I left the cover propped up on his desk and hoped for the best. When I rang him the next day, he was delighted. It wasn’t until 2005 that Chris finally got his way when CD2 of the Cuts compilation was christened Ceiling With Knives.

Toy Love album, 1980; cover designed by Jane Walker

I didn’t hear the vinyl version until after I returned to New Zealand, and probably didn’t play it a lot. A few spins to get familiar with it overall, get a feel for the total package as an object, play some tracks for friends and other interested people, that was about it. It was only when I met up with the band again and spent time with them during that first week of the New Zealand tour, that I became aware of how strongly they felt about the final pressings. I had noticed it was a little thin and less gutsy in parts than the sound embedded in my head after so many gigs and I suspected the band wouldn’t be entirely pleased.

The results weren’t ideal, I thought, but it wasn’t as if the album was a disaster. It would be fair to say that the band unanimously thought it was. Jane says she cried when she first heard the vinyl.

I suppose my initial response was influenced by a sense of relief that we’d got that far and all those songs were at last down on record. If I’d not heard of Toy Love before and had no idea where they’d come from, on hearing that LP for the first time I would have been knocked out. Anyway, I’m sure I thought the next one was bound to be even better.

Understandably the band had a different perspective, with most of their criticism directed at the lack of bass in the mastering for vinyl. It appears that the engineer had made an independent decision to clip the bottom end for some technical reasons, and the general feeling was that the cassettes sounded better than the final pressings. In my opinion that first album is not the total turkey that a few insist it is, being full of terrific songs and some good performances.

However, like most people familiar with this story, I much prefer the 2012 pressings that were remastered from a miraculously preserved DAT safety tape discovered in the 1990s; the original 24 track masters having been lost, possibly in a Sydney warehouse fire. I’m heartened that the band unanimously approves of the sound on reissues like the 2005 Cuts double CD. To me, these reissues also happily confirm that Todd captured the band more truly than the original release suggested, and although this particular strand of the narrative took about 25 years to be resolved, they all got there in the end.

Toy Love in Real Groovy, November 2011 - Photo by Simon Kay

--

Read: Roy Colbert reviews the Toy Love album for Rip It Up.

--

This article is an excerpt from A Toy Love Story, Terence Hogan’s memoir of his time with Toy Love. The complete story can be read at his website.