It can’t be long before the Topp Twins are featured on a bank note, so enshrined are they in the culture. In March 2018 two prime ministers turned out to honour Jools and Lynda Topp when a touring exhibition about them opened at the National Library, over the road from Parliament.

Helen Clark, Jools and Lynda Topp, and Jacinda Ardern at the launch of the Topp Twins' exhibition at the National Library, Wellington, 26 March 2018 - Mark Beatty/National Library of NZ

Dominating the large gathering were stalwarts of the many movements the pair have championed for 40 years: courageous campaigners for the rights of women, gays and lesbians, unions, and a nuclear-free New Zealand. The 2009 documentary Untouchable Girls was described as “the history of New Zealand in the time of the Topps” – and historians, archivists and activists were on hand to make sure it was recorded properly.

Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern revealed in her speech that she won the Topps’ caravan in a TradeMe auction; she bought the TV prop to use as a mobile electoral office. The seller was anonymous, and Ardern won with a bid of $1400. She described going to Jools’s farm to pick it up, trying not to look like a townie, despite her high heels. Then the dilapidated caravan’s door fell off.

Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern with Lynda (left) and Jools Topp, Wellington, 26 March 2018 - Mark Beatty/National Library of NZ

The Topps were touched by the presence of Ardern and Helen Clark. “It’s been great to feel the support of our women prime ministers,” said Jools in a heartfelt but typically teasing speech. “Well, almost all of them.” The mutual admiration didn’t stop Jools from demanding the banning of 1080 and better public television. Later that evening, only a few metres away, in an exhibition marking 125 years of women’s suffrage in New Zealand, the Topps were shown the petition demanding that women get the vote. Among the signatures – in copperplate calligraphy – are two great aunts, Charlotte and Myrtle Topp.

Earlier that day Jools and Lynda explained to AudioCulture that the political and the personal are inseparable in what they do, but so too is music. In the past couple of decades the widespread success of the Topps’ many television series have eclipsed the fact that, first and foremost, the sisters always were, and remain, a music act. Their television alter egos Ken and Ken, Camp Leader and Camp Mother – and many others straight from an A&P show –have overshadowed their actual personae.

“Sometimes,” says Jools, “people forget about our music, because they see the characters on television …” Lynda: “We make them laugh.” Jools: “… the most important thing is that the songs and the music have always been the vehicle. That’s the vehicle that got us from A to B, and a stage show. It’s the music that got us through the documentary.” Lynda: “All the characters have their own songs now. The music is number one.”

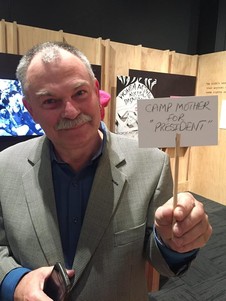

Bruce Topp, the twins' brother who gave them their first guitar, continues his support in 2017. - Topp Twins collection

The creation narrative of the Topps is now well rehearsed. How, while growing up on the farm of their parents Jean and Peter – at Ruawaro, near Huntly in Waikato – their older brother Bruce gave them a guitar and the book Play in a Day. Jools was immediately drawn to the instrument, says Lynda. “She read that book from cover to cover for that first day. And then she kind of threw it away. And that was it.”

Jools: “It did exactly what it said it was going to do on the front cover. Play in a Day. So I did. I learnt all the chords, in a day, and from that moment on I’ve never done any other thing with a guitar ever. I do play the guitar simply but I had a wonderful upbringing in the sense that I spent a lot of time down the back of the bus going home from Huntly College with the Māori kids in the back, where they would teach me the Māori strum.

“To play the Maori strum is pretty out there. You’re playing the drums, the harmonica and a guitar all at the same time.”

“To play the Māori strum is pretty out there. You’re playing the drums, the harmonica and a guitar all at the same time. Because you’re dampening the string, you’re using your hands, [Lynda: “You’re playing the rhythm as well.”] So I learnt it, and the thing is, when the Topp Twins sing there is no drums, there is no bass, we’ve just got one guitar and two vocals. So I’ve been playing percussion and guitar and finding different ways of how I would play that guitar. I found my own sort of reggae style, that isn’t reggae. Sometimes when we are alone we have to make things happen. That isolation is where originality comes from. You’re not being influenced by other people playing around you.”

The country influence is explained by an oft-told story of the sisters riding their horses to a neighbouring farm, where there was a 78rpm wind-up gramophone with discs by Australian yodellers and cowgirls Shirley Thoms and Judy Holmes. But the Topps’ mother would forbid them from taking their guitar on horseback expeditions. “So we’d ride like maniacs, wind the gramophone up, listen to the song and try and keep it in our head,” says Lynda. “Then we’d ride like the wind back home and get the guitar out. By the time we got home we’d sort of lost the tune. We became very good riders and horse women, but it did take quite a while to learn those songs and get the idea of singing and yodelling.”

One of the Australian 78s inspired Lynda to take up yodelling: ‘Pinto Pony’ by June Holmes. “I went into a ‘yodel coma’ I call it, and I just thought I gotta learn how to do that. I was absolutely mesmerised by the sound.” So she started listening to the gramophone intently – “There was no musical teacher that could teach me yodelling” – and went down to the back of the farm to practise.

“For a long time it sounded like a strangled cat,” says Jools. “There was a lot of practising, probably about five or six years before she actually sang publically with a yodel. I had no great desire to yodel whatsoever. I just tagged along on the coat tails of Lynda’s fame about yodelling,” she says, laughing. “It’s worn off on me. At a certain point now I can yodel but only if Lynda’s yodelling.”

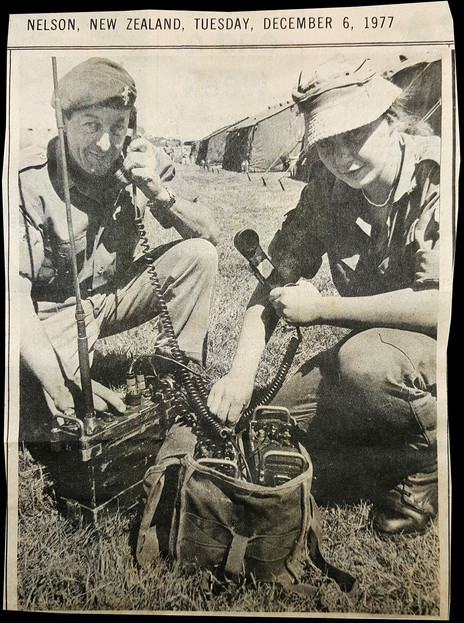

Lynda Topp in the Territorial Force Signals Platoon, Nelson, 1977 - MS-Papers-11685-09, Alexander Turnbull Library

In 1976, after leaving school, the Topps joined the Territorials. Their applications for the New Zealand Women’s Royal Army Corps are among the four metres of Topps papers held in the Alexander Turnbull Library. In answer to question 7B, “What should you take if you break something in the quarters?” Lynda writes, “Aspirin”. The examiner responds, “Very clever! But no marks”.

The Topps were posted at the Burnham Military Camp near Christchurch for six weeks. Lynda has described their stint in the army as, "Like a pyjama party ... with guns!"

Then fate took a different turn. Lynda: “We were supposed to go back to the Waikato, take over the dairy farm, and become Territorial soldiers: that would have been our life. But for some reason, we rang Mum and Dad and said, ‘We did our basic training, we’re coming home to look after the farm,’ and Mum and Dad said, ‘You’re not coming home to look after the farm.’

“We said, ‘What do you mean? That’s always been our vision.’ And Dad just said, ‘Look, if you come home and look after the farm you’ll be tied to it for the rest of your lives. Go and see the world.’ Which was amazing. Most country folks would say, ‘You gotta get back here, we’ve got to milk the cows tomorrow.’ But they said, go and see the world.”

The Topps’ world at that stage was Christchurch – “We’d gone overseas” – and so they decided to “jump train” and stay there. They soon met a dynamic woman singer who held them spellbound: Nancy Kiel.

Lynda: “She played in many bands, but the Little Baby Boogie band was the one she was playing in when we met her. She was amazing, she was technically brilliant, with the best voice, and the most amazing stage performance.” Under age, the Topps snuck into the Gresham Hotel each Thursday to witness Kiel in action, while the elderly couple who ran the pub turned a blind eye: “They knew that we were absolutely smitten. Absolutely completely and utterly drawn to that performance of Nancy Kiel. We weren’t drinking, we’d just go up there and dance. We just loved it, it was magic.”

Nancy Kiel, Christchurch Town Hall, 1974. - Photo by Kevin Hill

Kiel was the “Janis Joplin of Christchurch”, says Lynda. To Jools, “She was a rock star. She wasn’t part of the lesbian movement, she was part of the women’s movement. A lot of straight women were drawn to the lesbian world, because they saw themselves as being pretty out there: not identifying as lesbian but identifying as really strong, and they saw that strength in lesbian women.”

It was at this stage that Lynda and Jools came out. “Coming out as lesbians for us was never ever a big deal. It was just something that happened. Nancy had invited us to a party after a pub gig, and we were so excited that we were going out with a rock star, to a party. And everyone else got in their cars and drove off, and Jools and I were still walking at that stage, so we arrived a little bit late. There was a group of women, these short-haired women, wearing guardsmen’s jackets and stuff, in the corner. And I said to Jools, ‘Look at them, over there – we’re just like them.’ And Jools said, yeah, we’re just like them. And then somebody said to us, ‘Oh come over and meet the lesbians …’

“And we were like, lesbians? Lesbians? We must be lesbians! They’re just like us! And you know what, from that day on afterwards, we identified as lesbians. There was no kind of angst or, ‘Oh my god what’s our parents going to do?’, or do we have to fall in love first.”

When the Topps began writing their own songs, the personal and the political were inextricably linked, and this emerged in early favourites in their repertoire such as ‘Untouchable Girls’, ‘Friday Night Get Up’ and ‘Good Sisters Gone Bad’. “You know what?” says Jools. “There isn’t really much of a gap of that in our lives.”

Lynda: “At that time we were …” Jools: “... hugely political in our personal lives. We didn’t put on our one costume that said, ‘Here’s my political character, and here’s my personal character’. We were living a personal/political life.”

“ ‘Untouchable Girls’ is a “bit of a classic,” says Lynda, “it’s our theme tune, our signature tune. That was actually written by me,” she says, laughing. “Not that Jools hasn’t written a lot good songs, but that is our number one song. It started out very differently. The first line I had was ‘we’re dining out ladies tonight’.” Jools: “It started out as a whole group of gals just going out and partying.”

Lynda: “It’s just we were invincible, we can do anything, we were going out to party and everything like that. And it just didn’t have a feel about it, it didn’t come together. Then I was thinking, ‘What are we?’ What were we trying to get across?’ And Jools said, ‘Yeah well we’re untouchable untouchable untouchable girls’ and then it just clicked. The song that became our theme tune started off very, very differently.”

Over the past decade, says Jools, “I’ve pretty much written every song. Lynda comes along and says, ‘I think it’d be so much better if we had the verse …’” Lynda: “She’s the writer and I’m the editor.”

Jools: “It’s a collaboration of whether the bridge is right there, or whatever, and my timing is weird. And sometimes Lynda says, it’d be much easier this way, or something, and we’ll try that. So we’ve found a way: Lynda does the comedy, she’s the one who makes people laugh, I make the music, we’ve found our little niches of jobs to do to keep the Topp Twins rolling along.”

"Nuclear free" cassette re-issue of the Topp Twins' 1982 album 'Go Vinyl' - MS-Papers-11685-38-2, Alexander Turnbull Library

The Topps say that songs were often written for necessity, to support a protest. However, says Jools, sometimes a song just happens. The poignant ‘Calf Club Day’ is an example. “I dreamt it, probably about three o’clock in the morning, the whole song. I just woke up; I sat bolt upright in bed with a book next to my bed, and I wrote the whole thing in five minutes because I’d dreamt every single verse, every single picture that I’d seen of it. And another song called ‘Horse’ – that was a dream too.”

After performing their strident early classics, a song such as ‘Calf Club Day’ is a “curve ball” in a set, says Jools. “A lot of people come up to us and say, ‘I really love that song because it reminded me of growing up, and the first time I ever had to brush my calf and take it to school, it was a real moment, the grass smelt nice, and these moments we had’ … So we were painting pictures sometimes.”

The constant banter between the sisters inevitably creates situations where they both hear lines that are perfect for a song. Lynda: “The last song we wrote was a little song called ‘Tomboy’, which is about our growing up, and being called tomboys, riding horses and that sort of stuff. And that actually started down in Jools’ tack room: she had the guitar in the tack room where she’d been ridin’ the horses. And we were sitting on old sacks or what have you, having a cold beer I think, and then Jools picked up the guitar and she did this funny little riff or something and then the first line came out , which was … how does ‘Tomboy’ go?”

Jools can’t recall ‘Tomboy’ without a guitar in her hand.

Lynda: “It’s about, y’know, we don’t want to do the dishes …”

Jools: “Oh, ‘Way back when the girls had to do the dishes ...’”

Lynda: “… Learn how to cook and [simultaneously] look forward to mister and missus.”

“That wasn’t our lives,” says Jools, and Lynda elaborates: “We weren’t any of those things. And then it became that we were tomboys. And it was okay if you were a tomboy in New Zealand, because it means you grew up to be a lesbian! That was the idea of that song, it’s very interesting, it’s sorta country, and it’s got a very very [subversive] message.

“Sometimes,” says Jools, “we might sing quite a serious song, but what happens is that Lynda has this way of introducing the song in a funny way, so people will laugh, and in some ways that is really ... subversive. We’re up there, we make people feel really at home and relaxed and then – boom – we hit ’em with something a little bit weird or a little bit political, or we freak ’em out by coming off the stage and enter their area. They’ll go, ‘Hang on a minute: we’re the audience. Get out of our area.’ They’re scared we might work with them and all that sort of stuff. And that’s just us honing our way of how we work a crowd.”

Lynda and Jools Topp perform 'Untouchable Girls' at the opening of the exhibition celebrating their career: National Library, Wellington, 26 March 2018 - Mark Beatty/National Library of NZ

Apart from their exuberance and chutzpah, the most identifiable thing about the Topps in performance is their harmonies. Like countless sibling acts before them, from the Carters to the Louvins and the Finns, their approach to harmony stands apart. (Sibling harmonies seem to have something in common: in trying to hear themselves, or dominate the other, one voice is often pitched a little sharp.)

Every family that sings has its own harmony, explains Jools: “Every now and then what happens is we’ll be singing along and we’ll do this cross over, and a weird harmonic happens. We have to suddenly stop and go, ‘Wow that was weird, that freaked us out’.”

Lynda: “It’ll change, I’ll start off singing the melody line and Jools is doing the harmony and somewhere in the line of a song we’ll cross over and change. She’ll finish on the melody and I’ll finish off on the harmony.

Jools: “It’s a discord, when we change from that, right, and we’ve learnt how to handle that little bit of discord that happens along the way.”

Lynda: “It’s only a brief moment when the change happens, but now we just do it unthinkingly. We don’t sit down [and work it out]. We’re not technically brilliant but we like to be emotionally fantastic.”

Jools: “It just cannot be recreated; you can’t just say ‘I’m going to sing in the style of the Topp Twins’. Good luck buddy! Because you know we have our own timing and everything. Our very first recording, we were like, I’d play three beats here and then four beats the next time, and [the producer and musicians] didn’t know where the hell we were, and those guys said, ‘Well we don’t want to change how you sound’ – so they learnt how I played and then they had to undo 25 years of proper practical technical training and go, ‘This is weird, but it sounds quite interesting.’ ”

Lynda: “Because Jools and I would sing together, we’d do our family harmonies – twin harmonies – and Jools used to play around the music, around the vocals with the guitar, and fill in the little gaps and everything. So sometimes she would be a weird beat out from normal music …”

Jools: “I’m normally just a little bit in front of the vocals, not right with it.”

They feel a responsibility towards each other.

They feel a responsibility towards each other, says Jools: “There’s a sense that if you don’t get that right, it makes the other person not sound too good.”

The Topps’ first paid gig was in Christchurch, in a small coffee shop full of students wearing duffle coats and playing chess; the pay was $5 each and as many toasted sandwiches as they could eat. They played for four hours. Soon they got an offer from a larger café in Dunedin, the Governor’s Café, run by “two funky men who knew the student scene was going to be big,” says Jools.

Shifting up to Auckland in the late 1970s took the Topps to another level, although they began by singing in the street for their supper. Vulcan Lane, off Queen Street, quickly became their domain: they drew massive lunchtime crowds and soon got mainstream media attention. A regular in the audience was on the staff of the Students’ Arts Council, then a very active events arm of the New Zealand University Students Association, running national tours, especially during Orientation.

“They just rocked up to us and said we want you to do a tour round New Zealand,” says Jools. “And from that moment on we were big names. It suddenly went stupid. And [as with] students, we all thought we were invincible, we could change the world, no one could stop us from doing anything, we were all highly politically motivated. And it was amazing because every political moment in the world needs a song, so there we were, ripe for the picking.”

Recording demos for the Out of the Corners anthology at The Lab Auckland, 1982. From left: engineer Bill Latimer, Lynda Topp, and Mahinarangi Tocker - Bill Latimer collection

Right from the beginning their original songs had a political agenda; one of the earliest was ‘Graffiti Raiders’, which first appeared on the Web Women’s Collective compilation Out of the Corners (1982).

Lynda: “One thing that our mum taught us was she said, ‘You must never hate anybody, you can dislike someone but you must never hate anybody’ and ‘You must always let everybody have a go, or give everybody the same chance as everybody else’. So we had that instilled in us by our mother, and then when we got out into the big wide world, we saw and felt that there were injustices: women weren’t paid as much as men, and all that kind of stuff. So I think we saw all these things in the world that we thought, okay we’ve got to do something, we’ve got to write a song about that.”

Jools: “Nothing’s changed though.”

“No, says Lynda. “I think things have changed – we’ve been a part of all of those movements: the Springboks tour, the nuclear-free New Zealand, Māori land rights issues, the homosexual law reform bill. All of those things, and we wrote a song for every one of them, and the great thing about it is that – when you look back – we won all of those things that we were part of. We won every fight that we ever fought.”

Jools: “Some of those songs became the anthems for that movement.”

But how you put across those anthems is the key. “Anybody can sing a song these days,” says Jools, “there are thousands of people who can get up at a karaoke bar, they might even be better singers than us. But can they create a show that holds an audience for two hours? That’s the trick. You can’t just have music or the songs, you have to have a way of relating to the audience. So we never see ourselves as just musicians or singers, we certainly don’t just see ourselves as comedians, you see, we’re vaudeville! We’re old school!”

“The music is utterly important ... we’d never do a show without a guitar in our hands.”

Jools: “The music is utterly important. In fact the most important thing when it comes to the Topp Twins. We’d never do a show without a guitar in our hands.”

For all that, though, there is great satisfaction knowing you have been involved in challenging many political and social taboos, and been vindicated by history. “We like to think that we helped the gay and lesbian community come out, that we make it easier for them,” says Lynda.

“Just this morning we were in the airport,” elaborates Jools, “and a young man came up out of the blue and he said, ‘I just want to thank you for all the stuff you’ve ever done for all the gay community’. He was as camp as a row of tents ...”

Lynda: “He was probably in his early 20s, and we’re about to turn 60 …” (both laugh) “… so, you know, it’s nice that we’ve known that that has happened.”

--