AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

SJD

aka Sean James Donnelly, The Purple People Eater

Emerging from obscurity in the late 1990s as an idiosyncratic electronic artist, SJD (Sean James Donnelly) went on to confound his ardent fan base and staunchest critics by evolving into one of our finest songwriters, winning major awards along the way and becoming a trusted collaborator with first division legends Don McGlashan and Neil Finn.

It started in 1997, when a little-known bass player came up with some songs of his own, which he tested out on friends and friends of friends on intimate performances in lounges and kitchens, using just voice and acoustic guitar. The songs were introspective, haunting, and didn’t seem to quite belong to any specific tradition.

But it was a different sound that Donnelly introduced shortly thereafter on an EP’s worth of tracks by the fictional Delicious Food Band. Rather than heart-on-sleeve songs, this new project, shortly thereafter renamed SJD, was an experiment in judicious sampling, slicing and dicing into outrageous collages that somehow hung together as compositions.

Less than a year later, the self-released album, 3, formalised the SJD style. If those lucky enough to have heard his acoustic solo act had been gob smacked, they were knocked out of the ring by the album. Obviously DIY and made on computer gear groaning under the weight of his exacting demands, the record was full of moody grooves that somehow broached the dance world while hinting at real songwriting skills. In other words, he was New Zealand’s own Beck, without being in the least bit derivative of that star. Nevertheless, SJD clearly had similar abilities to collide worlds.

Already nearing 30 when his first recordings hit the 95bFM playlist, little is known about Donnelly’s pre-SJD life, so I pressed him for details about the formative years. It turns out that right from the beginning, he was a mixture of musician and technology-meddler:

“The start of it for me was about taping songs off the radio on an old reel-to-reel recorder,” says Donnelly. “I’d then drop in little links and things between the tracks, using rather a lot of speeding up and slowing down of the tape and using the overdubbing function to make crowd sounds, applause, etcetera. After that, it was endless overdubbing with a Casio VL-tone until I bought my first synth, a Roland SH-101, in my early teens.

“I managed to inveigle my way into the school band on synth and keys – kind of like a teenage Eno with floppy fringe and a Joy Division T-shirt, and spent most of my sixth and seventh form skiving off to the music room, which had two 2-track machines, which meant endless overdubbing and sound degradation!”

Donnelly reckons he filled around 40 cassettes with “synth ditties and soundtracks to imaginary films” before he briefly joined a Christian rock band, where he wrote his first “proper” songs, “a lot of them about nuclear annihilation and teenage depression … we were way too left of centre for the god-botherers.”

A big moment came in his early 20s when, playing in a post-punk-influenced band called the Love Popes, Donnelly picked up the bass guitar. His melodic approach to the instrument would play a big part in the future SJD sound. Later, he mastered the fundamentals of guitar to start a country-rock band called The Slaters, but “started messing around with samples and synths in my spare time, which sort of evolved into the first incarnation of SJD. I liked the results, because I could put ‘songy’ bits into the music but not get so sick of them, because there was a big cushion of instrumental weirdness surrounding them.”

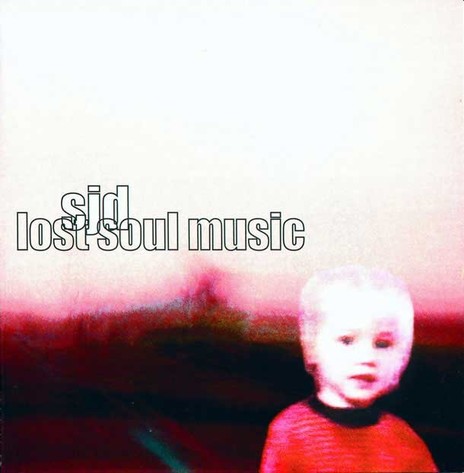

‘Lost Soul Music’ showed that a major talent had arrived.

Perhaps Donnelly sums up in that one sentence why so many were drawn to electronic music hybrids in the mid-to-late 90s: with the influence of hip-hop and trip-hop and techno and house and other dance styles coming through, traditional song structures seemed dull, if only for a moment in time.

While 3 was impressive, its successor, Lost Soul Music, released through Stinky Jim (Jim Pinckney)’s super cool Round Trip Mars imprint, showed that a major talent had arrived with its deft and skillful integration of new technology – electronics, heavily manipulated sampling – and old-fashioned writing and singing skills. And although the record only scraped to 50 on the NZ album chart, the song ‘Tree People’, with its hilarious sped-up vocal and humorous rhyming couplets, did own the 95bFM playlist in 2001.

Southern Lights (2004) saw Donnelly putting his electronics on the backburner with a set of classic 60s and 70s-influenced songs, while collaborating with a who’s who of hot names, including Don McGlashan (with whom he would subsequently appear as a sideman, and later perform together in The Bellbirds), David Kilgour, Paul McLaney, Anika Moa, James Duncan, Dominic Blaazer and local jazzers Dan Sperber, Kingsley Melhuish and Jim Langabeer. Making it to No.31 on the album charts, like Lost Soul Music it contained a song in ‘Superman You’re Crying’ that many felt could have been a smash hit.

“I just can’t get past certain beautiful sounds I hear from that late 60s and early 70s music,” Donnelly told me in 2004. “I’m crazy about that stuff.”

But the interior workings of the songs were something different. “At the time I was doing psychotherapy, which was a new experience for me, and I was feeling terribly threatened … you don’t know if people are on your side or not, you desperately want it all to be true because you want to come out of your shell and for it to be wonderful and life can be better, but you don’t know if it’s true. The song ‘Place Surrounded’ was getting inside the feeling of that psychological state – threatening and destructive at the same time. So, in general, the album has a few darker aspects.”

If Southern Lights dazzled many, 2007’s Songs From A Dictaphone struck perhaps the perfect synergy for the musically schizophrenic artist, somehow managing to successfully merge clever electronics with songwriting smarts. To date it’s his highest charting album, zooming all the way to 11. Once again subtly incorporating the talents of James Duncan, Paul McLaney, Sandy Mill, keyboardist Dominic Blaazer, drummer Chris O’Connor, as well as a small string section, it’s an album that many felt encapsulated and shone a light on what made SJD great, and struck a beautiful balance between searching and playful, groovy and ethereal, and every point in between.

If ‘Southern Lights’ dazzled many, 2007’s ‘Songs From A Dictaphone’ struck perhaps the perfect synergy for Donnelly.

After that, the following year’s Dayglo Spectres felt disappointing. Co-written by guitarist James Duncan, who became a partner in SJD over this period, the sound seemed willfully detached and ironic and guitar-centric, while the songs took a backseat. But if Dayglo Spectres represented a sideways misstep, to many, Elastic Wasteland (2012) a whole four years later was just one step too far into the abyss. It was the first SJD album since his debut to completely fail to chart, and received a critically mixed reaction.

In 2015, Donnelly spoke about the album, which won the prestigious Taite Music Prize in 2013:

“That’s my version of synthpop, but it coincided with being the middle of winter and being a little melancholic, so it ended up being quite a melancholic version of synthpop. I realised after I did that a lot of people wrinkled their noses because they didn’t get it at all. Because when you hear people’s synthpop it has a late 80s, early 90s sound about it. The glories of synthpop for me were Soft Cell, early Depeche Mode and Orchestral Manouevres In The Dark … stuff that was influenced by Kraftwerk, and influenced by soul music, and either had super electronic sounds or warm lush sounds, but wasn’t that brittle sounding stuff, that brittle plasticy sound, which is that Michael Jackson and Madonna stuff.

“It’s a very miserable album,” he admits. “I always think there’s a bit of hopefulness in there, but really, it’s quite despairing and sad. But I had to make that album, no choice.”

What’s missing from this story, of course, is that from 2004 onwards, Sean Donnelly had become a busy lad collaborating with and helping other artists with their music, as well as a short period adding jingles to his income. With the persistence of an ox, he’s never stopped writing and making his own music, but increasingly, he’s been invited into the musical world of others, and in turn that’s changed his approach.

It began with Don McGlashan, who was still in the tentative steps in the wake of the immolation of The Mutton Birds of reestablishing himself as a solo artist.

“Somebody gave Don a copy of the very first thing I did,” Donnelly told me in 2010. “I got to meet him and he played some euphonium on Lost Soul Music and he was trying to do his songs solo, so I helped him get his solo thing up and going a little bit. The first incarnation had me on loops, and then it turned into a band thing. I’ve had an association for the last eight years or so with his music, so I know him pretty well. I always think we’re quite kindred musical minds. I was always a fan of his music, and thought he was a great lyricist and melodicist, and he always had a slightly left of centre way of looking at things, particularly The Front Lawn and that first Mutton Birds album, I really did love that stuff, and Blam Blam Blam. He always throws a weird chord in there, and the melody follows in a slightly bent way but it’s really great.”

The Donnelly/ McGlashan union went all the way with the first incarnation of a side project, The Bellbirds, which also featured longtime SJD vocalist-supreme Sandy Mill along with keyboardist and film composer Victoria Kelly.

By 2010, Donnelly had also been invited into the circle of Finn, and became a key player on Neil Finn’s project with his wife Sharon, Pajama Club.

By 2010, Donnelly became a key player on Neil Finn’s project with his wife Sharon, Pajama Club.

Explaining the recording nearly a year prior to its eventual release in 2011, Donnelly said: “It started with Neil and Sharon just mucking around being a rhythm section, him playing drums and her playing bass. We built them up almost SJD-style, layer on layer, with Sharon singing all over them. Neil’s trying to sound a bit different from how he normally sounds, and he plays some amazing guitar. The initial thing was that band ESG – New York new wave disco. You know, can’t really play your instruments but having a good time doing it. But it’s way, way more widescreen than that now.”

Subsequently, Donnelly toured the Pajama Club project with Neil and Sharon to the UK, but missed the final dates when he nearly died from a mystery illness. Happily, he fully recovered from the ordeal, and Neil Finn went on to provide significant contributions to the latest SJD album, Saint John Divine (2015).

In 2010, Donnelly told me how much he’d love to record his next album in Finn’s Roundhead Studios, but how it was out of his reach financially. “I’ll see how it goes, I don’t want to take the piss, but I’d like to get a bit of a cash injection from a record company. Otherwise I’ll just record it in my own home studio. But Roundhead is a brilliant place to record, it really is, it’s not for no reason that it gets touted as a premier recording studio. It’s more than the fact that it’s got everything a musician needs. It does have a fantastic vibe there. Neil really loves music, and he really loves all the underground stuff that’s happening in New Zealand.”

As it happened, the award-winning Elastic Wasteland was recorded all by himself in his cramped home studio, but finally, on Saint John Divine, Donnelly got the chance to record the whole thing at Roundhead. Of all the SJD albums, it’s the most organic-sounding, with little in the way of electronic enhancement, but solid performances from the usual players (James Duncan, Chris O’Connor, Sandy Mill) and with Neil Finn contributing piano, Wurlitzer, electric guitar and backing vocals.

The critical reception and general level of interest for Saint John Divine have both been spectacular, while Donnelly himself sees it as easily his best to date.

“For me there’s depth in these songs that I haven’t quite achieved before. A lot of the ideas on the earlier albums seem half-baked to me now. I still like the idea of small kernels of songs with a lot of instrumental embellishment, but there’s too many bits in the music, and it sounds like it’s not as truthful. Some of it’s a little bit too conscious of trying to sound clever, and hiding behind things. I feel like a better person for having made those last two albums, because I feel like there was more honesty to it. Maybe that’s all it is – it’s stripping away some of the obvious cleverness, some of the contrived elements in the music so that it’s more of an outpouring of my heart and soul. Clever is just like a joke I’ve heard too many times and it’s not funny.”

– Gary Steel, 2013

--

Since the release of Saint John Divine, SJD’s musical life has been multi-faceted, reflecting his wide skill set and respect in the industry. Between the producing, performing, composing and co-writing, there have always been new SJD releases.

“The thing I have learned about myself,” he told AudioCulture in February 2022, “is if I have a project in mind, hopefully not too well defined, but something that I can launch into and feel like I’m vaguely working towards accomplishing something – I can get a lot of inspiration out of it. I love doing that.”

As a commercial composer, Donnelly enjoyed – sometimes endured – a stint in advertising, contributed to the World of Wearable Art stage shows and even fell into the niche of sports documentaries with Chasing Great in 2016, The Freeman in 2017, and Born Racer in 2018.

He also immersed himself into the behind-the-scenes world of the APRA Silver Scroll Awards, being musical director of the 2016 awards show and joining the judging panel in 2021, although the former job suited him much better than the latter. Reflecting on the experience a year later, he said, “I’m not sure I do want to judge other people’s music. I can be a little bit judgmental anyway ... I try to tone that down.”

That being said, his long list of collaborators indicates his critical ear is appreciated by other musicians, whether it be as a producer, co-writer or mentor.

“[When producing] I like a genuine collaboration. I like when I can go in and be a fan of somebody, that’s cool. To go in, listen to my favourite artists and go ‘I really wish they’d do more of this, or do more of that.’ And I’ll just unashamedly steer them in that direction.”

His working relationships with Delaney Davidson and Don McGlashan continue, and other collaborators include Anna Coddington, Sandy Mill, Deryk (aka Madeline Bradley) and Caitlin Smith, to name a few. Donnelly describes his collaborations as “built around friendships” and “fit to purpose”.

“With Delaney we’ve had a few sessions where I’ve gone down to live with him, stay for a few days and we just jam out and write songs. With Don, of late, he doesn’t actually really want me anywhere near music, probably because it’s a strong flavour … But he’ll get to the point where he has something and wants some serious critical [listening].”

“I mean, there’s sort of a caveat, that is I’ve never written a hit single, and I’ve never been involved in a hit single, I don’t really know what one is … But the thing I’ve generally found in the ‘non-hit-world’ is that if you like a piece of music, if you’re excited about a piece of music, generally speaking that is one that other people will be excited about. It’s just your own instincts.”

He continues to tinker on his own original material. “It is a muscle you need to flex.”

As always, he continued to tinker on his own original material. “It is a muscle you need to flex.”

In late 2018, Donnelly began drip feeding new and deliberately short songs charmingly nicknamed “miniatures” on the SJD Facebook page. Seventeen of the succinct tracks, around 60-90 seconds in length, eventually formed the album Miniatures 1, released in May 2019.

“There’s a melancholic strain running through the new SJD Miniatures collection, but when the songs stay short, it comes with a certain stoicism,” said William Dart on RNZ in August 2019. “Laying out 17 songs in 21 minutes makes the album something of a brag book for Sean Donnelly’s skill in concocting electronic backdrops. Indeed, if he were a set designer, in Auckland in the 1950s, he’d have had no problem in taking us Around the World in 80 Days without relinquishing our seats in the little Grafton Theatre.”

Speaking to AudioCulture, Donnelly made the connection between crafting 17 micro songs to his time in advertising.

“Something I often thought about when I was doing ads, but I really thought about when I was doing Miniatures, is just ‘how can I make this tune as immediate and as catchy as possible?’ You know, taking into account the fact that it’s me writing it, in my little weird sensibilities.”

The title Miniatures 1 suggests it would be the first in a series, and that was the intention, but a little steam was lost when the album didn’t cut through as intended.

“I definitely feel proud of those songs. It’s just, what are you going to do? I mean, we’re all drowning in an ocean of music … You just turn it on like a tap, so it’s not even a matter of getting lost in it, you automatically come from a position of being lost in it and you have to somehow climb out.”

A number of the Miniatures 1 tracks were extended to full length songs, but they didn’t make the cut for SJD’s upcoming album, Sweetheart.

“It’s a sort of a game of two halves.” Donnelly says of Sweetheart. “The first half, I suppose, is synth pop. And the second half is more a kind of band-y, acoustically styled kind of thing, which are the two styles of my music that have been sort of evident over the years.”

His recent touring life has been very social. There was his sad-song covers project with Julia Deans in 2017, he joined McGlashan on his Free Flight NZ Tour in 2018, and was part of the ensemble of musicians on the Come Together tribute shows, for both the Abbey Road and Live Rust outings.

At Otago University, Donnelly is exploring narrative-driven music: “Musicals, rock operas, concept albums ...”

Donnelly is living in Dunedin and completing the Mozart Fellowship, Otago University’s year-long residency for composers. Sweetheart was finished in Dunedin, after beginning its life at Donnelly’s home in Auckland and Roundhead Studios. Now Donnelly is spending the residency exploring narrative-driven music.

“Musicals, rock operas, concept albums, that kind of stuff. Things that have a sort of narrative flow behind it … people have said before that some of my songs sound a little bit like they’re from a musical.” He’s unafraid of the “cheesiness” (his words) of those genres, and in fact is a little excited by it.

“There’s a thing that happens when music – I think I played with it a little bit with Miniatures – with music that risks being cheesy, but also risks being fun, and risks being quite joyous as well. It’s a refreshing thing I find about Generation [Z] ... earnestness has really come back massively into style. I think irony is almost out, really.”

– Update by Rosie Howells, March 2022

Sean James Donnelly - multi-instrumentalist, songwriter, producer, vocals, bass

Donnelly’s Taite Music Prize win in April 2013 included a heavy trophy and $10,000 in cash.

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air