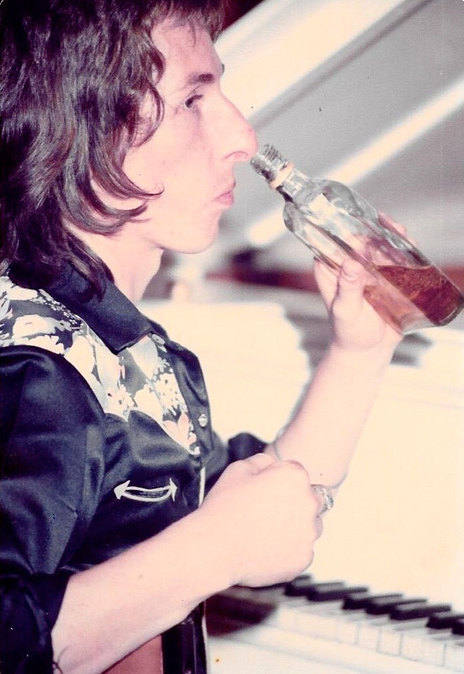

Fuelled by a massive sponsorship deal with Jim Beam, Ritchie Pickett & The Inlaws burnt brightly and partied hard for a short period of the 1980s with relentless touring and perhaps still New Zealand’s best country music album, Gone For Water.

Ritchie Pickett & The Inlaws’ Gone For Water, released 1984

But they were never going to last. Alcohol and the constant grind of long periods on the road combined to inflate egos and create tensions and bitterness that broke the band apart before they could record a follow-up.

As the 25th anniversary of its 1984 release loomed, rumours abounded of a long overdue CD repackaging of Gone For Water and even a possible one-off reunion gig.

Bandleader Ritchie Pickett had apparently recovered from his latest brush with death – a 2007 alcohol-induced mid-gig collapse – he had spent time in rehab and was making noises about treading the boards again.

Guitarist Dave Maybee took his last drink on December 30, 1985, and was producing and performing in Raglan, Jimmy Wallace was playing bass in a family band in Whangarei, and teetotaller Noel Lamberton was still drumming and president of the Bay of Plenty Blues Club. Only second guitarist Kevin Coleman had retired from the music scene, after a stint on bass with Hard To Handle in the late 1980s.

Although the 2009 milestone came and went without fanfare there were still hopes that Gone For Water would eventually be digitally remastered and released for the first time on CD with additional demos that had been locked away in Stebbing Recording Studios since the band’s 1985 demise.

But any hope of a reunion was laid to rest with the passing of Ritchie Pickett from a heart attack after a long battle with the bottle, in March 2011, at the age of 56.

By then the former bandmates had buried their differences and were able to look back at The Inlaws days with great fondness. In mid-2008, with the 25th anniversary of Gone For Water a year away, they were interviewed individually for possible liner notes to a CD release or a commemorative magazine feature. Neither of these eventuated.

The story begins with Ritchie Pickett, well known on the touring circuit throughout New Zealand in the 1970s as singer and rhythm guitarist of rock’n’roll revivalists Graffiti. He joined Think in time to record their We’ll Give You A Buzz album and to cross the Tasman Sea with them.

Think struggled in Australia and parted ways and Pickett found himself in a band managed by “one of the head honchos in the Mr Asia organisation”. His music career was going nowhere and he was getting deeper into the drug culture.

In 1980 he was rescued from Sydney and taken to Waikato Hospital with liver dysfunction and cancer. He was given a month to live, but later claimed his substance abuse had saved his life, slowing down the disease.

Ritchie Pickett at the NZ Country Music Hall of Fame in Taupo, 1981. One alcohol-charged gig there was said to have inspired the Gone For Water track Last Night I Let The Bottle Get On Top.

During a long recovery Pickett reacquainted himself with the instrument his mother had made him have lessons on as a child. “Because I couldn’t stand up and play the guitar, so I sat at the piano and started playing, and just started getting into writing. It was all just country stuff,” he said.

He met Morrinsville country music identity Bernie Eva, who introduced him to the music of Merle Haggard, and would travel to the Morrinsville Country Music Club to see some live music.

Pickett admitted being in denial of his country roots through the 1970s until he happened upon Elvis Costello’s My Aim Is True LP late in the decade and realised the storytelling of Hank Williams and Lefty Frizzell he had grown up on was still alive.

When he was well enough, the New Zealand Country Music Association hired him as musical director and he would put backing bands together for their various affiliated clubs’ annual awards shows throughout the country. This was his reintroduction to playing live.

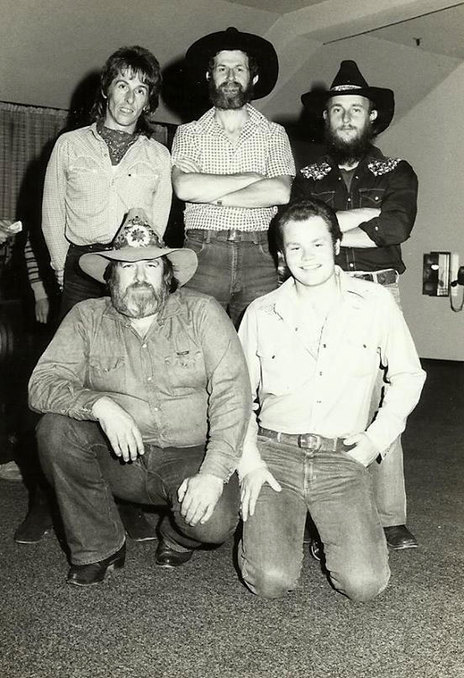

An early incarnation of Ritchie Pickett & The Inlaws

He began producing LPs and singles for the likes of Janice Ramage and Gerry Merito for the Kontact label, as well as writing songs for some artists. In the studio down time, his own Ritchie Pickett Band recorded a version of Gary Stewart’s ‘Your Place Or Mine’, which was released as a single. The band consisted of Pickett (piano and guitar), Bruce Dennis (drums), Pete Bell (bass) and Geoff Martin (guitar).

On another occasion, after finishing a Ramage single at Auckland’s Harlequin Studio, Pickett, Martin (on bass) and drummer Martin Williams recorded the old Sutherland Brothers and Quiver hit ‘Arms of Mary’. Kontact decided not to release the song.

By now Pickett had come under the Country Gold Promotions umbrella, touring with and backing such artists as Brendan Dugan, Gray Bartlett and Patsy Riggir. Meanwhile, Bartlett and Dugan had been generous with their praise of Pickett and he was soon drafted onto the television show That’s Country, heightening his profile in country music circles even further.

Ritchie Pickett all dressed up for That’s Country in the early 1980s - Gary Sammons collection

Host Ray Columbus and the regular cast welcomed his arrival on the show. Singer Noel Parlane said Pickett was a breath of fresh air and his songwriting ability brought a lot of respect. “It was something no-one else was brave enough to do.” Pickett was also a great addition to the end-of-filming parties.

He did, however, bemuse his That’s Country cohorts with the oft-repeated claim that he would be “gone by 29” just like one of his musical heroes. “He always said he wanted to live like Hank Williams,” Parlane remembered. Williams had died at that age in the back of a Cadillac on the way to a show.

One night in Tauranga, Pickett chanced upon duo Dave Maybee and Sid Limbert performing a rootsy blend of country music and blues at the local Cobb & Co Restaurant. Among the pair’s repertoire were some of the songs Bernie Eva had taught Pickett.

Guitarist Maybee and bass guitarist Limbert were already experienced touring musicians who had worked together in Smokestack, early incarnations of the Midge Marsden Band and the legendary Raglan Mudsharks.

Pickett got talking to the pair and soon they were performing sporadically with drummer Paul Kunac. The show was made up of Merle Haggard, Jerry Lee Lewis and hard country covers as well as Pickett’s ever-increasing original songbook. At the time, Pickett was writing four or five songs a day and keeping two of them.

“Over this time period the three of us (Maybee, Limbert and Pickett) were also signed via a management contract to Country Gold Promotions,” Maybee said, “so were being utilised in a variety of configurations and line-ups as backing/session players for many different country artists.”

An RCA Records publicity shot for Ritchie Pickett & The Inlaws, 1984. Left to right, Jimmy Wallace, Ritchie Pickett, Noel Lamberton, Kevin Coleman, Dave Maybee.

Sometime during this period Pickett first used “The Inlaws” as a band name at a Masterton gig that also featured Australian songwriter Allan Caswell. “The earliest Inlaws incarnations happened pretty much by default and came about via Country Gold,” Maybee said.

The Inlaws brought in pedal steel guitarist Errol Shute when they were booked to appear at the Littleweed Festival in Katikati in January 1983, where advertisements billed them as “Dave Maybee & The Inlaws featuring Ricky Pickett”.

Also on the Littleweed bill was a Tauranga band, whose name has long since been forgotten, featuring 19-year-old guitarist Kevin Coleman. He recalled of the occasion, “We each received a cupful of joints on arrival at the gig and a square of straw to sleep on.”

Pickett was so impressed with Coleman that back in Tauranga he invited him to sit in with The Inlaws. “You’re that Kevin Coleman boy. Come along for a gig with us.” Aware of Pickett’s fame on That’s Country, the guitarist didn’t hesitate. But it would be a few months before he was a permanent fixture.

Coleman had come up through the ranks of the Eastern Districts Country Music Club in Auckland but had lost his way when his parents split just before his 15th birthday. After sitting his final School Certificate exam he caught the bus to Tauranga, where he stayed.

When Limbert went his own way, Pickett and Maybee brought in young Whangarei bass guitarist Jimmy Wallace. It was on a Country Gold trip to Fort Worth, Texas, where Pickett and Wallace first played together, backing Gray Bartlett’s ‘Freight Train’ instrumental and the like in front of 20,000 Americans.

They had briefly met through the NZCMA’s awards circuit, and Wallace had been involved with Bartlett and Brendan Dugan since the late 70s. Born in Scotland in 1962, Wallace emigrated from England at the age of 12 with his parents and two younger brothers. Both parents played country music and young Jimmy had grown up with it.

Drummer Paul Kunac had also departed, replaced briefly by Bruce Morley. Country Gold would sometimes book this line-up as Double Anything, and Pickett made himself extremely unpopular with Country Gold management the night he carved that band name into the boardroom table at the Papakura RSA. Double Anything would occasionally combine with fiddler Cath Newhook’s Gentle Annie band to create a full-on western swing outfit.

Double Anything, early 1980s. Clockwise from top left, Ritchie Pickett, Bruce Morley, Dave Maybee, Jimmy Wallace, Errol Shute. - Charmaine Pickett collection

Another of the Country Gold alumni, Noel Lamberton, became the permanent Inlaws drummer. Pickett’s former bandmate in the ill-fated Think, Allan Badger, had earlier introduced him to Lamberton, late of Hamilton band Flight X-7.

Lamberton, then in his early 20s, had been playing professionally from the age of 14 and had already toured with ex-Space Waltz frontman Alastair Riddell, attained his Diploma in Sound Engineering in Australia and built a couple of studios in New Zealand.

Each member continued working outside The Inlaws for most of 1983, but demand for the group began picking up and Wallace reached a pivotal point, giving up the Kenny Rogers support with the Gray Bartlett Band to play with The Inlaws at the Royal Hotel in Opotiki.

By the end of the year, The Inlaws were in full swing, building up a good fan base touring themselves – with Selwyn “Buck” Jones as road manager and Bruce Godfrey mixing sound – or backing other artists.

According to Pickett, The Inlaws were fiercely proud they were country and would advertise the fact. “It would probably keep people away rather than draw them in,” he laughed. The line-up had settled on Pickett, Wallace, Lamberton and the dual guitars of Maybee and Coleman.

Ritchie Pickett & The Inlaws, 1984. Left to right, Jimmy Wallace, Kevin Coleman, Ritchie Pickett, Dave Maybee, Noel Lamberton.

“Pretty much from the get-up, Kevin and I worked on the twin lead thing – Allman Brothers, Wishbone Ash – and it became part and parcel of our originals,” Maybee said. “But it was really more to do with best practice arrangement principles, as we had two lead guitars and keyboards, apart from all the vocal elements, and needed to structure all these parts cohesively. It was creative, it was fun and it worked!”

Ray Columbus had instantly become a fan of Pickett’s songwriting when the two joined on That’s Country, and he now started working to obtain a record deal for the band. “Ray is a gentleman. I got to know him on That’s Country. He would read me the riot act when I stepped too far,” Pickett later said.

He somehow wrangled a sponsorship with Jim Beam – reportedly worth between $50,000 and $60,000 – and a contract with RCA. “He saw The Inlaws tackling a whole genre that hadn’t been touched, in original New Zealand country music,” Pickett said. “He was our champion, a huge champion of New Zealand songs.”

In the new year, with Pickett and Coleman living in Tauranga, Maybee in Raglan, Wallace in Whangarei and Lamberton in Rotorua, the band hunkered down in the basement of Buck Jones’ Raglan home and worked up the songs for the album.

“It was a magical time,” Coleman said. “I was astounded with how well it went. The harmonies were something we worked on and the dual guitar lines fell into place. It all clicked instrumentally.”

“Ritchie would give us the song, we’d work out parts. We were so excited about the music,” Wallace said. At the end of the week they tried the arrangements out at the Raglan Hotel before demoing the songs with Bruce Godfrey as engineer at Auckland’s Stebbing Recording Studios.

With Columbus as producer, the album sessions began in Stebbing’s brand-new sunken B studio, but it soon became evident that the project was also a good opportunity to iron out the studio’s teething problems.

Ritchie Pickett & the Inlaws - Gone For Water, side 1 label, RCA, 1984.

The band set up emulating a live gig, with the guitarists standing, and there was very little overdubbing. The recording went smoothly because the band were so well rehearsed, but they did find it difficult to get the energy up in the sterile nine-to-five studio environment.

“Stebbing’s was all done by the book,” Lamberton remembered. “If you wanted more treble you had to apply for it in triplicate. It was very old school. It was hard to be creative.”

While Pickett and Columbus worked well together – “Ray Columbus can get me to sing properly,” Pickett would state – Maybee found it difficult to hide his resentment of the way the project was progressing.

“Production-wise it was problematic as we were guinea pigs debugging the new studio,” he said. “Plus production techniques were fairly staid. However, overall the performance values outweighed the production and post-production issues.

“Recording the album was fairly straightforward, as we all knew our parts well having played most of the tracks on the road before, apart from a couple of tracks Ray wrote which he insisted we rehearse and record until the band flatly refused to!”

Early on, Maybee’s daughter fell ill and he had to take off to Hamilton Hospital. “He couldn’t make all the sessions and put his parts down later,” Pickett said, including the heartfelt vocal duet on ‘I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry’.

The Hank Williams cover had been a last-minute addition to the song list after the band had baulked at recording the Columbus material. “It was Ray’s idea to do it with two vocals,” Pickett said. “I backed it up. Dave didn’t know it so came up with a different melody.” The song also features harmonica from Wallace’s dad, Jim Senior.

Coleman found dealing with Columbus difficult. “It was us versus them for Noel, Jimmy and I,” he said. “The minute we were finished we would go to the bar.”

The recording was completed in a week and Columbus spent another week mixing. Meanwhile, Pickett decided to name the album Gone For Water after a painting of the same name by New Zealand artist Joy Neighbour he had seen at a Tauranga gallery. “It summed up where I was at – drifting,” he said.

The photo on the back of the album showed the band at Gunfighters Restaurant in Auckland enjoying the sponsor’s product. “We thought we couldn’t have a full bottle in the photo, so we drunk half of it,” Wallace remembered. Even non-drinker Lamberton sported a glass for show, although at gigs it was strictly, “Five whiskeys, five beers and a lemonade for the drummer.”

Ritchie Pickett & The Inlaws, 1984. Left to right, Jimmy Wallace, Dave Maybee, Ritchie Pickett, Noel Lamberton, Kevin Coleman.

Below the photo was a typical piece of Pickett cheek – “If you’re reading this album cover in the record shop either buy it or move along as I’m sure there’s a queue behind you.”

When Gone For Water was released, The Inlaws were disappointed with its sound. “The Bruce Godfrey demos sounded better,” Lamberton said. “The demos had a bit more heart and soul.”

“We weren’t in on the mix,” Wallace remembered. “It was ‘We’ll call you when it’s finished.’ We were disappointed with the mix. There was some weird reverb on the guitar. It was disappointing. The process was great, but I felt sorry for Ritchie.”

However, 24 years later Pickett said given the opportunity he would remaster the album but not remix it. “Ray was confined to an unfinished studio,” he said. “It’s a production of its time in a bad studio. I was very proud of the band. It was a great live band, but the LP doesn’t truly represent the band.”

If the production was questionable, the songs were anything but. Of the 12 tracks, nine were written or co-written by Pickett, there was the Hank Williams cover, a song by Australian mate Allan Caswell and the disused ‘Arms of Mary’ from a couple of years previous, now remixed by Columbus and Tony Foster-Moan.

The second track was one of Pickett’s most enduring, ‘Honky Tonk Heroes’. “Halfway through I was trying to think of more dead country music artists,” Pickett said, “so I rang Janice Ramage for more names. She came up with Jim Reeves and Pasty Cline. That was one of the first songs written for the band.”

There was also ‘Barmaid/You Win Again’, co-written with Maybee and Sid Limbert, which dated back to Limbert’s time in the band and was cleverly married to part of another Hank Williams gem.

The set closed out with ‘Yes, We’ll Leave the Lights On’, a tale of Kiwi girls on the game in Kings Cross to support their habits. Co-written with Allan Badger, it had started life as a ballad but was worked into a rocker by The Inlaws during the week in Raglan.

The band went on the road in support of the record, at first with Ray Columbus as special guest. “We toured full-on,” Maybee said. “In fact, I think the longest was around three months.

“We did a lot of gigs on the pub and festival circuit, but a lot of the RSA, cossie club circuit gigs and tours came via Country Gold Promotions. And, again, the band was utilised for backing of other artists as we were very capable of crossing country, western swing, blues and rock’n’roll. The constant touring took its toll, however. Sex, drugs and rock’n’roll was a big part of the lifestyle.”

Ray Columbus on tour with Ritchie Pickett & The Inlaws, late 1984. Left to right, Ritchie Pickett, Kevin Coleman, Noel Lamberton, Jimmy Wallace, Ray Columbus, Dave Maybee.

Coleman remembered touring and playing six nights a week from Invercargill north. “There’s no town we didn’t play,” he said. “There were times in tin-pot towns we were given a full reception, treated as kings. It was a wonderful experience.

“Touring in New Zealand there was a mixed reception for country originals. The further south we went, the better off and the more fun we had. We were the sole band on the road doing country originals. We tended to drink and smoke the money we made, but we loved the lifestyle.”

“The Inlaws had a lot of improvisation,” Lamberton said. “Dave would go off on a tangent and the band would follow. It was really creative and the dual guitar work was great. Everybody sang – four-part harmonies were no worry.”

Back cover of Ritchie Pickett & the Inlaws' Gone For Water, RCA, 1984

After a gig at the Gladstone Hotel in Christchurch, The Inlaws filmed a video for the first single ‘Arms of Mary’, but the video would never be completed. Wallace remembered a cherry picker on the back of a Land Rover, with a fire truck hose creating rain as the band walked in step across a railway line.

That New Year’s Eve, the 32nd anniversary of Hank Williams’ death at the age of 29, Pickett found himself that same age and fronting The Inlaws at a poorly attended gig in Napier. He had always said he would be “gone at 29”, and it was just a month until he turned 30.

“Ritchie was really drunk,” Wallace recalled. “There were only two or three people there and he made a nuisance of himself. He rang me at 3am and said he was going to top himself.”

“There were six people and they didn’t like us,” Coleman said. “Ritchie smashed a new SM58 (microphone) over his piano and stormed off. We did a set with just Dave and Ritchie returned for an angry last set. We woke up to a $500 booze bill and he reappeared very sheepish after that.”

“I decided I was going to die,” Pickett remembered. “The band threw a party for me and all chipped in together.”

Ritchie PIckett & the Inlaws - Gone For Water, label side 2, RCA, 1984

Ritchie Pickett & The Inlaws travelled to the Tamworth Country Music Festival in January where they performed at the Locomotive Hotel and supported the John Farnham-fronted Little River Band. “John Farnham was a lovely guy,” Pickett said. “Standing at the side of the stage while they played was an epiphany.”

The first gig at the Locomotive almost went off the rails when Wallace, travelling on a British passport, was held up flying into Australia and didn’t arrive till halfway through the show. Coleman had had to substitute on bass.

Although The Inlaws were a resounding success with the Tamworth patrons, the festival delivered a blow to the relationship of Pickett and Maybee. While Pickett was all about preaching the gospel of his own band, Maybee spent most of the time busking with bluesman-turned-country-singer-songwriter Al Hunter, still three years off making his Neon Cowboy album, and jamming with many of the Australian pickers.

Pickett claimed to have foreseen the end of The Inlaws when the band’s bus picked up Hunter, sporting his ever-present Stetson, hitchhiking back into Tamworth and Maybee delivered the throwaway line, “He’s a proper country singer, he wears a hat.”

They held it together long enough to return to Stebbing Recording Studios to demo tracks for a second album, with Bruce Godfrey again engineering. Pickett songs such as ‘Angry Words’, ‘Theme From Claw’, ‘Too Many Too Manys’, ‘I Thought I Heard a Heartbeat’ and Maybee’s ‘Guitar Playing Man’ had been added to the repertoire since Gone For Water while ‘Jennylee (Does the Horizontal Foxtrot)’ dated back to That’s Country parties.

Ritchie Pickett & The Inlaws, 1984. Left to right, Jimmy Wallace, Kevin Coleman, Noel Lamberton, Dave Maybee. Ritchie Pickett in front.

“The follow-up album for Gone For Water was recorded, demoed with The Inlaws, and I thought it was a good album,” Pickett said. “But we never got to finish it, the band exploded before then. It was more focused, more a band thing. Gone For Water was more me.”

There was no definitive reason for the band’s early 1985 break-up. “The whole thing imploded,” Lamberton claimed. “Dave spat the dummy.”

Coleman reckoned he was out of the loop as far as the political side of The Inlaws was concerned but recalled it was “pretty traumatic, like a family break-up. Major decisions were made with no input from me.”

“There was a fallout between Dave and Ritchie,” Wallace said. “The Inlaws were only big enough for one of them. Dave was a menace at times.”

Wallace claimed the event that finished The Inlaws was the Go New Zealand package tour that included Pickett as a feature artist along with the Yandall Sisters, Suzanne Prentice, Midge Marsden, Tom Sharplin and Michael-Roy Croft in March 1985.

Coleman was part of the Go New Zealand band, as were former Inlaws Sid Limbert and Bruce Morley, Lamberton was on board as lighting engineer but Wallace was only offered a job as a roadie and opted out of the six-week trek.

Pickett said he and Maybee just stopped calling each other. “Dave was hard to handle, but no more than I was. There was a lot of bad blood between Dave and I after that. We had another trip to Texas, to Fort Worth, coming up but we called it off.”

“The Inlaws was a very creative time for us all, myself included,” Maybee admitted, “but Ritchie and I had reached a tipping point in our alcohol-fuelled professional relationship/friendship and we had to part company. Being hell-bent on self-destruction was not my cup of tea anymore.

“On the downside, there is also the fact that none of us in the band – Ritchie swears it was the same for himself – have ever received a cent in royalties or sales from the album and to this day have never been told what the deal was that was done between Eldred Stebbing, Ray, Ritchie and RCA. This was one of the issues that gave rise to serious discontent and fuelled further bitterness between Ritchie and band members.”

There were half-hearted efforts to continue the band with former Rockinghorse guitarist Kevin Bayley taking Maybee’s spot, and a financially disastrous trip to Sydney with Bayley and Mike Farrell on guitars. But in the end Ritchie Pickett & The Inlaws simply limped to a halt.

In an ironic footnote, the trailblazing Gone For Water that had practically redefined the New Zealand country music genre was pipped for country album of the year at the 1985 recording industry awards by the industry-safe and family friendly Patsy Riggir’s You Remind Me Of A Love Song.

Stebbing Recording Centre released Gone For Water by Ritchie Pickett & The Inlaws digitally in 2012.