Lyall Morris Laurent was born in Auckland on 21 May 1925 and lived there all his life. He had poor eyesight and was a life-long member of the Royal New Zealand Foundation for the Blind. His great-grandfather, Rudolph St Laurent, was a French merchant sea captain who sailed to New Zealand with his wife Elizabeth and decided to settle.

Several of their 14 grandchildren were born with congenital cataracts, including my grandfather Morton, Lyall’s dad. Like three of his brothers, Mort became a piano tuner – a good profession for blind men. They were well known around Auckland and the Waikato, as many homes had a piano in the 1910s and 20s. My grandma, Hazel, was a pastel artist, baked her own bread using wholemeal flour (a bit alternative then), drove her husband to his tuning jobs, helped him with piano repairs and, like grandpa, was a pianist and choral singer in the Anglican Church.

Lyall went to the Parnell school for the blind and was deeply involved with “the Foundation” all his life (the institution educated many prominent musicians, including Julian Lee, Joe Papesch and his son Claude Papesch, Tai Paul, and Eddie Low). He hit his teens during the Second World War when Auckland was full of American servicemen. With his friends he would hang out around the army camp in Auckland Domain, and the soldiers were generous at sharing their jazz records and cigarettes with the young enthusiasts. As he had already been learning piano at school and had a very good ear, he quickly took to jazz, as did his brother Clive, who played trumpet. It wasn’t long before they were putting together their first band. Lyall’s parents had a sleep-out at the back of their Mt Eden home and they allowed the boys to turn it into a rehearsal room.

It’s a credit to my grandparents that they were open and encouraging of their sons’ interest in what was, at the time, considered radical music; many of their generation in the classical world would have disapproved. My dad showed me the same generosity when I took to rock music in the late 1960s, setting me up with an open-reel tape deck in my bedroom so I could record the songs I liked off Radio Hauraki. He was really interested in Hauraki and what they were doing, even though the music wasn’t his thing. He generally had an open ear to whatever was going on; it was he who introduced me to Jethro Tull around 1970, before any of my friends had really heard them.

Lyall Laurent played his first paying gig at the age of 15

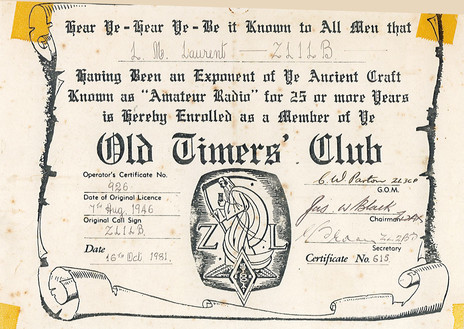

Lyall was a professional pianist all his adult life and played his first paying gig at the age of 15. He worked for the Braille and Talking Book Library by day and in dance halls, bars and restaurants at night, mostly around Auckland. He was an active ham radio operator – his call-sign was ZL1LB – and loved hi-fi. We had a Roller 12UX bass-reflex speaker cabinet in our lounge, bigger than an oven or washing machine. It was driven by a valve amp built by his friend and bandmate Merv Thomas, and it sounded great. Lyall had a large collection of open reel tapes, vinyl (jazz and classical), and later cassettes and CDs. He listened to everyone from Ella Fitzgerald to Pat Metheny and, after he retired, he set up a voluntary business repairing and recycling cassettes for the use of blind people.

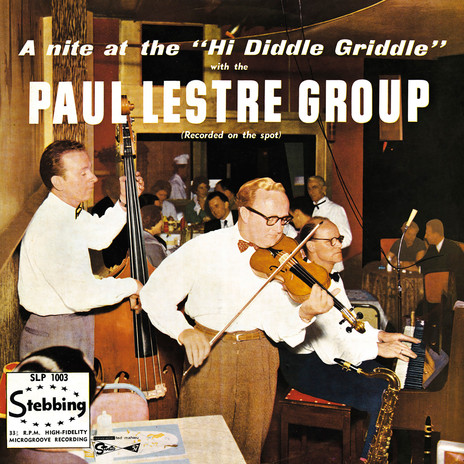

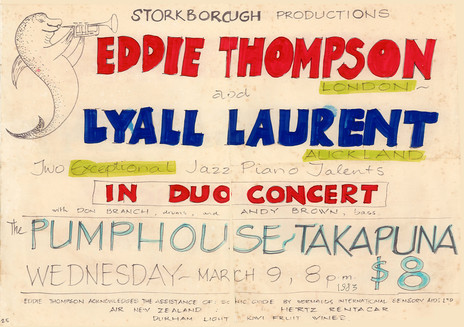

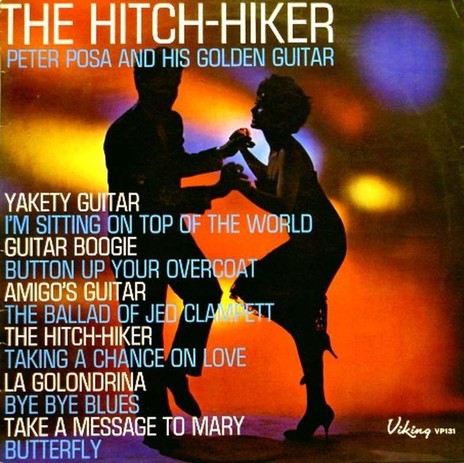

As a child I remember going for summer holidays to places like Waiheke and Kawau islands where Lyall had summer residencies at one resort or another, and to Tauranga for the jazz festival. Lyall was resident pianist for several live radio shows including Have A Shot, and he performed a number of shows in the Auckland Town Hall, live to air, as part of the broadcast band for one jazz celebrity or another. He recorded sessions for Stebbing, Mascot, Radio New Zealand and other studios. One curious pairing was that he backed Johnny Devlin (or was it Johnny Cooper?) in some early shows as there were no rock’n’roll pianists around at the time and a jazz player was the nearest who could get the feel. He played piano for Peter Posa on the 1964 LP The Hitch-Hiker for basically the same reason (I sat on the studio floor drawing pictures and keeping quiet during that session).

Over the years Lyall became renowned for his encyclopaedic chord knowledge, huge repertoire and exceptional left-hand technique. He had a really fine-tuned ear; my grandad (the piano tuner) had perfect pitch and Pop told me that his own pitch was relative, but his ability to instantly recognise the key of any song makes me think he was being modest. Although he played by ear he had an excellent grasp of theory and often helped me identify chords, even stuff by Hendrix and Cream. Lyall also had synesthesia – the experience of seeing colours related to sounds – and part of the reason he liked complex chords was that they created such an interesting light show for him.

Lyall played at virtually every jazz venue in the greater Auckland region, plus many restaurants and private functions of all sorts, both as solo pianist, or as part of a large number of groups. He played for several years with Epi Shalfoon’s band, then for a long stint with Merv Thomas and his Dixielanders. In the mid-1960s the Station Hotel Quartet had the redidency at the downtown hotel of the same name, with Morrin Cooper on vibes, Bob Ofsoski bass, and Brian Spence drums (in the following years these four worked together in many permutations).

He played with legendary

Band Leaders such as Epi Shalfoon and Merv Thomas

Venues at which he played include the Crystal Palace (with the Dixielanders), The Orange Ballroom, St Seps (the regular dances held at Holy Sepulchre church hall in upper Khyber Pass Rd), The Hi Diddle Griddle (with the Paul Lestre Group), The Gables in Herne Bay, Monte Martre in Lorne Street, White Heron Lodge, Sorrento, The Orient restaurant – a solo residency there for several years – the Sheraton, and the Hotel Intercontinental. In fact, think of a local venue and he probably played there. He had an eight-year residency (shared with Jack Randall) at the London Bar, and was in Tommy Adderley’s band for Tommy’s last few years. For quite a few years Lyall was secretary of the NZ Musicians Union.

In the Auckland scene – and it probably happened elsewhere – a lot of the musicians knew each other, and there was a high level of mutual respect. I recall my dad conversing with other musicians where they’d mention some player or other, and the tone was almost invariably positive. This was reflected in the way many local gigs came together. Somebody – often Lyall – would get a phone call offering a gig for a band. Lyall would then get on the phone to a few of the guys he knew and cobble a combo together. There was almost never any rehearsal as everybody knew the standards and trusted each other. Instant bands were thrown together, and they were always good.

Occasionally someone would throw a party and a bunch of the musicians and their families would converge on a house on a Sunday afternoon (they’d all have worked Saturday night) and of course a jam would develop. Even as a kid I knew these were pretty hot sessions.

Lyall died on 17 January 1999 of bowel cancer. He was one of those people who never seemed to catch a cold, and his final, short illness is my only memory of him being in poor health. I remember him telling me that, in 50 years, he had almost never missed playing somewhere on a Saturday night, and he normally played three or four nights a week.

I was sad that he didn’t get to see the dawn of the new millennium, as he had been looking forward to it; he had an excellent memory for dates, significant milestones etc. Lyall was a people person and loved nothing better than to stand in front of the stereo with a couple of friends, drinking a beer and talking enthusiastically about their shared love of the music.