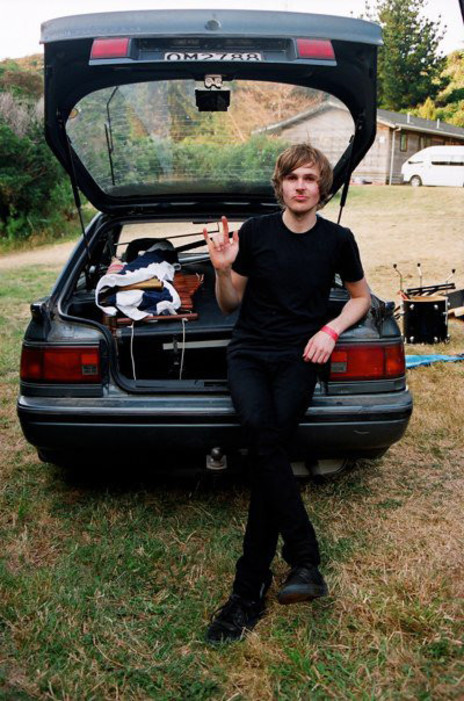

Piano lessons began around the time he started primary school. By intermediate he was also learning bass guitar and trumpet, and had electrified his mother’s nylon-string guitar with what was “basically just a telephone receiver” plugged into the family’s National Panasonic stereo. It sounded horrendous and Grayson loved it. Distortion!

He taught himself guitar chords from his mother’s songbooks, and made his first attempts to write songs of his own. “Looking back it’s kind of funny,” he says. “My first song utilised every chord in the book, in a kind of irrelevant way. It probably had, like, 16 chords. I discovered minimalism a bit later in my life, thankfully.”

His first “band” – he uses the term advisedly – was a hip-hop trio with a couple of intermediate school friends. “Just drums, bass and vocals. We just made rhymes about our classmates, using somebody’s brother’s music equipment that was sitting out in the garden shed.”

At secondary school he was recruited by classmate and Metallica fan Shreejan Pandey. The son of Nepalese academics, Shreejan was an aspiring shredder with an entrepreneurial streak. His band was called Twink, Grayson recalls with a grimace, “but it could have been Vivid or Biro”.

“Shreejan was really adamant that this band is going to record and release something and we have to have 12 songs. We’re, like, 15, and the songs are terrible, very juvenile and embarrassing to look back on. But objectively, getting a bunch of 15-year-old boys to do anything, it’s kind of a miracle. There are photos of us sitting at a table, putting the CDs together, sticking the labels on, assembling them …” Shreejan Pandey even insisted the group include multi-media such as press-kits and video on their CD-Rom, pushing their cheap CD burner to its limits. The teenagers then organised a release concert, selling the discs for $10 each on top of an entry fee.

Palmerston North is often characterised as a cultural backwater, and seldom as a cornerstone of the New Zealand music industry – but that’s to outsiders. For a young musician in the early 2000s the place afforded opportunities that would have been unimaginable in a bigger city. Twink recorded and launched their album at The Stomach, a non-profit, all-ages music studio, venue and rehearsal space, established in the late 80s with support from the local council.

The Stomach was a haven: a non-profit, all-ages music studio, venue and rehearsal space.

For Grayson, The Stomach was a haven and he spent as much time there as he could, especially after his parents split up. He’d be there before and after school, practising on the house equipment and learning his way around the studio’s 16-track recording facility. Eventually he was offered the job of janitor, which gave him a set of keys and access to the studio and gear any time it wasn’t in use. In this way he began to assemble material for his first solo recordings.

For his 2002 debut EP Abstract Arrival he recorded the songs at home onto a cassette, then transferred them to ADAT at The Stomach. In the studio he would play along to the home demo, one instrument at a time, effectively using the demo as a click track, overdubbing drums, vocals, guitars and keyboards until the studio’s 16 available channels were all filled up. Hayden Sinclair, the house engineer, operated the mixing desk. Applying some of the lessons he had learned from the entrepreneurial Shreejan, Grayson designed and packaged the discs himself and sent them out to reviewers and radio stations around the country. A second release followed, the longer Behind Locked Doors, recorded and distributed in the same DIY manner.

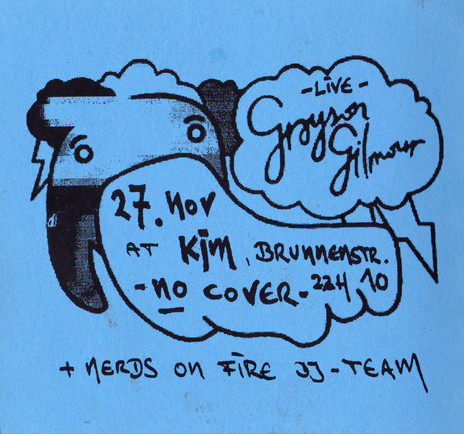

Student radio stations were the first to take notice and began playlisting tracks. Reviewers asked, “Who is Grayson Gilmour?” wondering whether it was a made-up stage name, and what the story was behind the mysterious Palmerston North postmarked packages.

By 2003 he had finished school and moved to Wellington. Though he had been to summer school workshops in jazz bass at high school, it was his fascination with the writing of music, more than performing or improvising, that led him to enrol in composition at Victoria University.

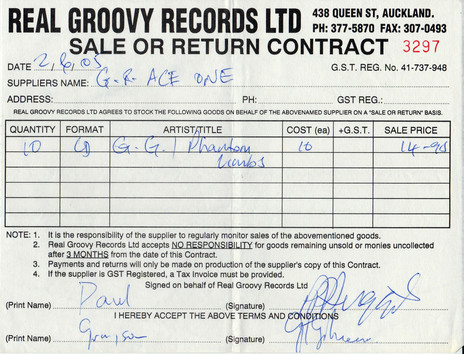

To support himself he worked at Real Groovy Records’ Wellington store. Record stores in Palmerston North such as Tower and Mango had been a critical part of his musical education. “The people that were working in those record shops, they were personalities. You could hang out and just talk about music at those places all afternoon if you wanted to. And they would be ordering all kinds of curious stuff from all over this place. They’d play you songs, like ‘you’ve heard this, but I bet you haven’t heard this!’ So I got this informal kind of education as well, just by hanging out with them. A kind of cultural capital.”

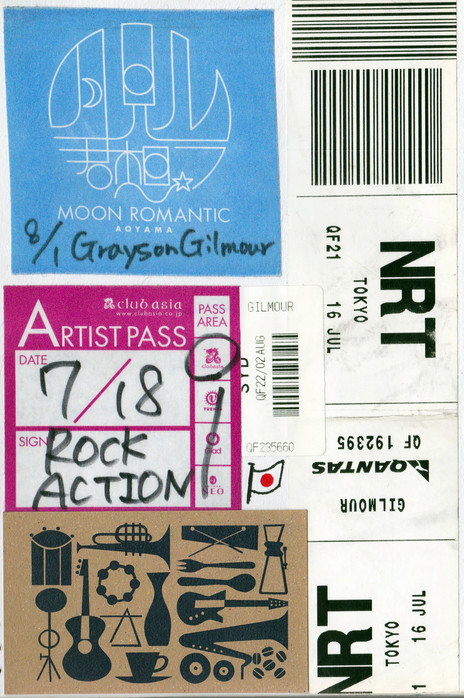

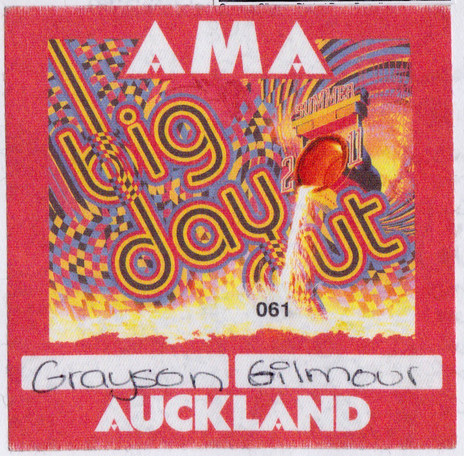

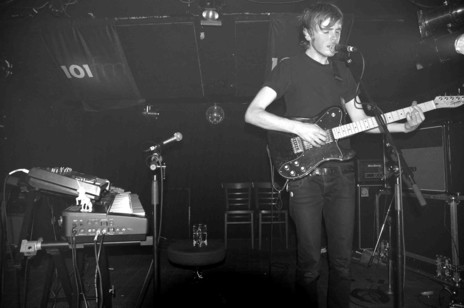

That year also saw the formation of So So Modern, who would record and tour internationally, playing more than a thousand shows over the remainder of the decade. But Grayson’s performances as a solo artist remained scarce. “I just wanted to focus on recording when I was doing my own music. I had this idea that if I could be hearing music from other people from the other side of the world on a CD, maybe that whole equation could play out for me to someone else? Like I’ve never seen this person play, but I’ve got their album and I think it’s great.”

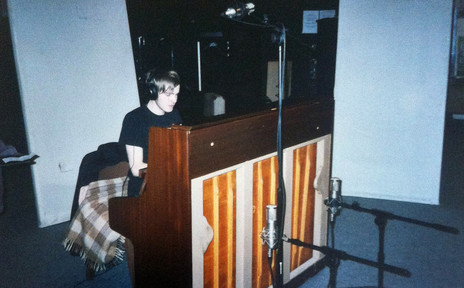

To record his next album Phantom Limbs, he returned to Palmerston North. Though it showed a leap in musical sophistication, it was made in much the same manner as his earlier releases. ‘One of the things I love about The Stomach was there was no computer, no Pro Tools or anything like that. It was one of the things I was lucky to experience because [analogue recording] was at the end of its lifespan and there were studios where you’d be paying more for computers and software. So I was getting this really great insight into old-school recording processes, where you’ve got two or three people on the desk and you’ve all got your hands on the mute buttons.”

‘Phantom Limbs’ was remastered at a Wellington studio, housed in a former S.I.S. bunker

Encouraged by sales of Phantom Limbs, Real Groovy store manager Paul Huggins had Mike Gibson remaster the album at his Wellington studio, housed in a former SIS bunker. Grayson would go there to record his next album, titled – alluding perhaps to the studio’s secretive history – You Sleep, We Creep. This would be the first time computers were involved in one of his records, and again Grayson seized a learning opportunity. With Grayson leaning over his shoulder, Mike Gibson would joke, “Maybe don’t watch everything that I’m doing because then you’ll just be able to do it yourself!”

“And I did end up learning it all and doing a lot of it myself, not out of wanting to cut corners but I was just generally interested and curious to do it.”

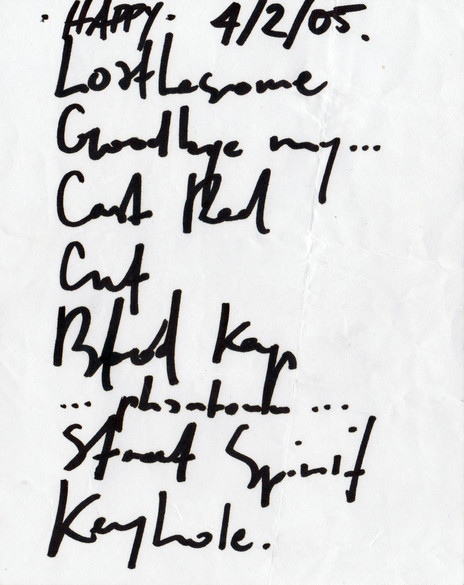

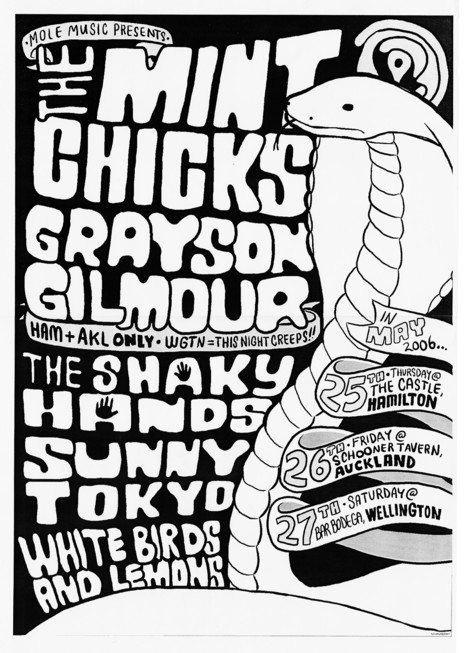

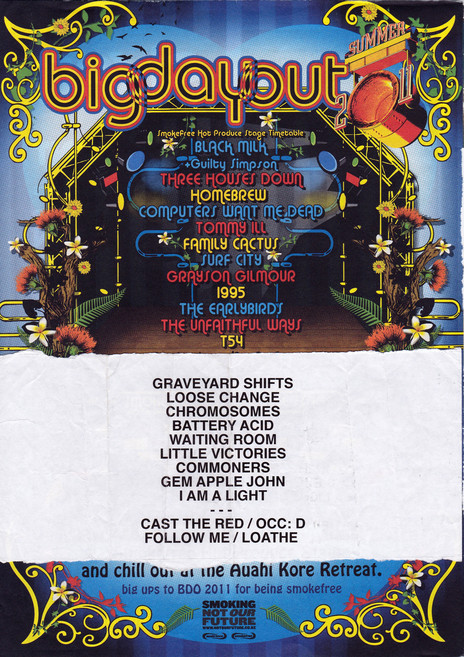

You Sleep, We Creep’s release in 2007 also saw Grayson touring for the first time as a solo artist, on a bill that included The Mint Chicks and Cut Off Your Hands.

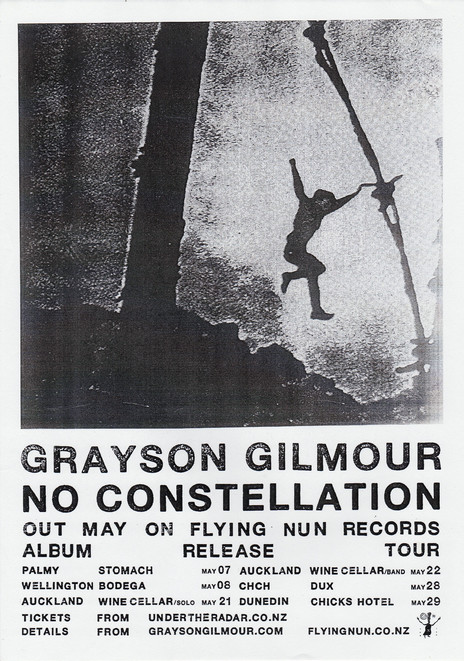

His next album, No Constellation, was made in between tours with the busy So So Modern. As Mike Gibson had foreseen, Grayson recorded most of it himself. Though he intended to release it independently like his previous discs, its completion coincided with the 2010 relaunch of the Flying Nun label and Grayson became the first new signing of the reborn imprint. Reviewing the album for local website Under the Radar, Brannavan Gnanalingam noted how it was “unashamedly melodic” without being predictable, summing it up as “an excellent album from an artist who’s young and adventurous enough to warrant still being called precocious, and assured and complex enough to sound like it was made by a veteran.”

With Flying Nun’s reputation and reach, Grayson found his audience growing internationally. He also had his first opportunity to fulfil a long-term ambition to write music for films. Through Sally Tran, who had designed costumes for So So Modern, he had got to know video editor and skateboard enthusiast Liam Bachler. “Liam wanted me to make some music for a little weird commercial for the skateboard magazine Manual. And so I made this funny kind of sound piece, an atmospheric, guitar-feedbacky soundtrack to this little film.”

Bachler was working with director Mark Albiston, creator of Sticky Pictures who would use music from Phantom Limbs in his television documentary about Sir Peter Blake. “It was almost like the film scoring cues they were after, but it was just this kid around the corner, making this dramatic music. I started to get the idea people were interested in using my music because it had this kind of emotional drive to it.”

Albiston went on to hire Grayson to score his first feature drama Shopping, which Albiston wrote and directed with Louis Sutherland. By this time Grayson had also completed the soundtrack to The Most Fun You Can Have Dying, the 2012 debut feature of director Kirstin Marcon. The film’s diverse cues required a wide range of moods and styles, from searing punk rock to reflective abstraction. Grayson proved he could do it all.

“I don’t want to be the guy who is doing this [film] music just because it’s a paycheck.”

More soundtrack offers followed, though Grayson was selective. “A lot of the films [I was offered] had this really weird undercurrent of, like, casually racist comedy, and I couldn’t handle that. I don’t want to be the guy who is doing this music just because it’s a paycheck.”

He has tended to work with filmmakers who have already built an emotional relationship with his music, either through his records or scores he has written for other films. But he also builds an intense emotional relationship with the films. It would be hard to surpass the intensity of Robert Sarkies’ tele-feature Consent: The Louise Nicholas Story, the true story of Nicholas’s two-decade battle to take a group of police officers to court for raping her as a 13-year-old schoolgirl. Though the score won Grayson the APRA Best Original Music in a Feature Film Award in the 2015 Silver Scrolls, it took its toll on the composer. “I mean, it was nothing compared to what happens in the film, but it’s my own kind of emotional trauma that I got so invested in writing music for it that I can’t actually go back to it without crying. Occasionally I’m asked to present some of my work [for Consent] to a masterclass or workshop, and I’ll have to walk to the side of the room and suck up my tears before I can keep talking.”

The year Consent was screened (2014) he released Infinite Life, his second album for Flying Nun. Summing it up in my annual top 10 for RNZ’s The Sampler, I noted the “strong affecting melodies … wrapped in densely woven blankets of sound” and the detailed arrangements: “the musical equivalent of a pointillist painting”.

Though So So Modern had been on a hiatus since 2013, they reconvened for a one-off gig in 2016 to mark the 15th anniversary of the Camp A Low Hum festival. By this time he was already working on his next solo album Otherness, which would be released the following year. In the light of all his film work, it is not surprising that its soundscapes are often sweeping and cinematic, yet it is also a reminder of what a melodic singer and songwriter he is. If the title suggests estrangement or alienation listen and it seems to mean the opposite: an awareness of the “other” and of an experience shared.

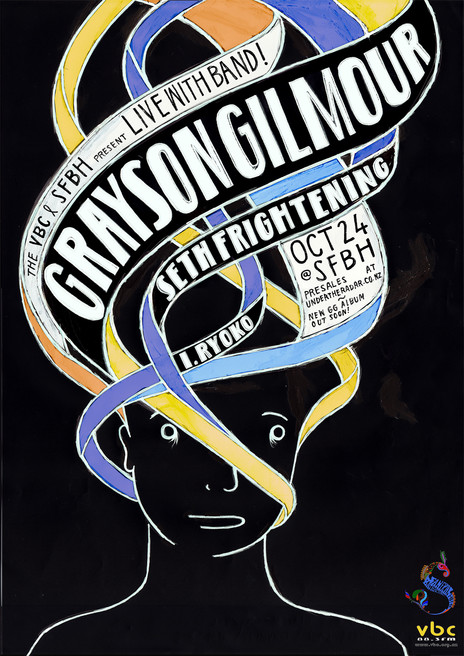

The years since Otherness have been taken up with fatherhood, film (including working with American composer Nathan Johnson on a television series for Joseph Gordon Levitt), tutoring at Massey’s School of Music and Creative Media Production, and preparing his next album. It’s the longest he’s ever taken between releases, though he clearly hasn’t been idle. When I meet him at his home studio in the hills above Island Bay he plays me a few of the tracks. He explains that though the music is complete, the vocals are still temporary. Even with the guide vocals, the melodies I’m hearing are as sumptuous as ever, yet what I’m struck by most are the strong, danceable rhythms. For this album he has used two drummers, Cory Champion and Olivia Campion. It’s a pairing he began using during shows for Otherness, when he realised that the beats he had created for the recording relied on the combination of a half-time groove combined with double-time percussion.

For the first time Grayson has been creating his solo material with a view to performing it live.

Now for the first time he has been creating his solo material with a view to performing it live. “My fascination has always been with recording, writing and producing music. But I always had the So So Modern outlet and now that I don’t have that in the way that I used to, I actually do miss playing. So this new album is much more geared to playing live. I need to move my body, so the BPMs are faster and the rhythms are a little bit more interesting.”

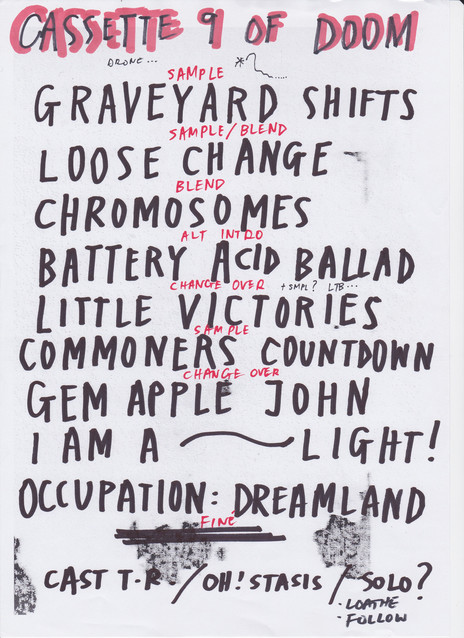

While we are listening he unrolls a giant sheet of pattern-making paper covered in multicoloured text, all written in pencil in a neat spidery hand. I recognise song titles with notes beside them about instrumentation. Elsewhere on the sheet are scraps of notation, fragments of lyrics, production ideas. It dawns on me that what I’m looking at is a map of Grayson Gilmour’s musical mind. “I need to write things down and look at them visually to make sense of it all,” he explains.

“Sometimes ideas change names or get updates or merge with other ideas. Like, these are all guitar ideas,” he says, pointing to one section of the chart. “And these are little piano ideas. And these are all like, electronic ideas and oh, maybe there’s like three different EPs sitting over here. It’s pretty chaotic but it is a map and it’s functional and it is basically a way for me to just make sense of all of the ideas that are floating around.”

He says he has been keeping these kind of mind-maps for a long time now; this one represents the past year’s work. Like a piece of his music, you can study it closely and follow the myriad ways all the different bits join up, or just stand back and enjoy it as a vast and colourful composition.

Things take longer than expected, especially when one is juggling a music career with parenthood, teaching, and soundtrack work. But finally, more than a year after we talk, a release date of 3 November 2023 is announced for his long-in-the-making album. The songs I heard in their embryonic form are now complete. Powerful kinetic polyrhythms and textured with lush layers of keyboards. There is nothing readily identifiable as guitar – though I hear harps and violins – while Grayson’s words and melodies have never been more upfront or confiding. The title Holding Patterns reminds me of the colourful mind-map he showed me. Perhaps it also refers to the almost six-year gap between releases. But more than anything it suggests the rich aural mosaics that await the listener.