“Dunedin definitely took a bit to get used to,” she says. “Leaving the airport with two of my sisters and my dad, they said ‘do you like luxury cars?’… we proceeded to get into a 1958 Vanguard that was three different colours! It had a door that would fly open when you went round corners.”

They lived in Harbour Terrace, in the heart of Dunedin’s colloquially known suburb of Studentville, and she attended Logan Park High School, one of the fertile breeding grounds for Dunedin’s nascent music scene. Her time at Logan Park also stirred a political streak in her. “Something that really interested me at the time was student rights. There was … very little here. And, so I got super-duper involved.”

Musicianship was brief during her youth. “For my 11th birthday, I coerced my parents into buying me a guitar … which they dutifully did, thank you very much, and it was difficult for them, because we didn’t have very much money,” she recalls.

The guitar was strung for right-handed players – challenging, as Griffin is left-handed.

“They bought me a guitar, and they bought me a book … not being in a musical family, it didn’t occur to my ma and pa that I probably needed some lessons!”

The guitar was strung for right-handed players – challenging, as Griffin is left-handed – and remained elusive for a few years.

By 1979, she desired change. This meant heading back to Canada, and Calgary’s punk scene, reinventing herself, and starting her own journey as a musician. She defines it as an escape.

“I needed to escape from here for various reasons … I don’t know that I could have reinvented myself here, I was trying, but it wasn’t really working.”

Calgary offered much, and she “learned a lot about music, and a lot about myself, and learned that I wanted to play music.”

The first instrument she chose to learn was the bass, buying one from her hairdresser, and calling it “one of the most difficult instruments I’ve ever played … the action on this bass was really high, which meant I had to push really, really hard to get the strings to the fretboard. So I started calling it … the Golden Gate bass,” she says, laughing.

She plays bass left-handed and – years after her early attempts – learnt to play guitar left-handed, but on right-handed instruments.

“I learned how to play guitar at people’s houses,” Griffin explains. “I’d pick up Bruce Blücher’s Hofner, and it was upside down, and I’d start playing on that. Pretty much all guitars were right-handed, except for Shayne’s [Shayne Carter], and his never came out at parties ... I learnt to play upside down, and I have done ever since.”

Griffin stayed in Calgary for two years, buying a ticket back to New Zealand rather than a car. “One day I just thought ‘ah, fuck it,’ and bought a ticket ... I came home, and I was kind of a new person, and haven’t left again.”

Fate, or destiny (if you believe in it) can throw plenty of curveballs. If Kathy Griffin had not decamped to Calgary and its music scene, picking up a bass and learning herself, would she have become involved in Dunedin’s emerging alternative music scene? One can only speculate.

But one night she attended a show in the Donald Reid building in Dunedin’s now-partly-gentrified Warehouse precinct (currently housing the Heritage Kitchen café), and saw Christine Voice perform with her Elevators bandmate Martyn Bull. She and Bull hit it off immediately.

Bull was an extremely talented multi-instrumentalist. “That man could pick anything up, and in 20 minutes in he would be playing something on it.

Through Martyn Bull she met many Dunedin musicians, including her future bandmates in Look Blue Go Purple.

“He started showing me things to do. It was hilarious – I was all over the fretboard … he showed me how to do scales, so we practised scales … a lot! I don’t know notes, I don’t know chords … I just do it by feel.”

Through Martyn Bull she met many Dunedin musicians, including her future bandmates in Look Blue Go Purple, Cyclops, and The Cartilage Family.

The pair formed bands together – initially the Bel-Curves with flatmate Selwyn Andrews, Jeff Harford, and Peter Gutteridge. “We rented a practice room in the Donald Reid building,” she remembers. “I think we played Peter’s songs. ‘Big Mouth’ was born there … it was an amazing bass line … Selwyn made it up and showed me it. That all fell apart, because these things do ... Peter was a force then with his own music, and did insist on things being precisely how he wanted them.”

Bel-Curves played in a number of venues around Dunedin, including The Pitz and The Cook, as well as private parties. One such party was at a friend’s home in Purakanui, where Martyn Bull’s ashes were later scattered, a walnut tree marking the place.

Next, they teamed up with Norma O’Malley as the Permanent Tourists, playing twice in their brief career. One gig stands out: playing with a capella group The Neanics (Lesley Paris, Denise Roughan, Jane Dodd, and Rachel Phillipps). They had worked up a cover of the Velvet Underground’s ‘After Hours’, and so too had The Neanics – it was their only song of the night. “We played before them. They were standing there going ‘that’s our song!’ ‘After Hours’ became a song we would do, and Look Blue Go Purple would do, it would often be the last song we’d do of the night.”

Personally, life was taking a concerning turn. Martyn, now drummer in The Chills (with Martin Phillipps and Terry Moore), was unwell, and subsequently diagnosed with leukaemia. This put a new perspective on everything, and Griffin started researching natural therapies, the start of her second career as a naturopath. Her interest in natural remedies began when Bull was initially diagnosed.

“I dove into a whole lot of books, and started learning about herbs, and I taught myself how to do reflexology,” she says. “We did all these things, we did stave off the leukaemia for quite some time – when he was diagnosed, he was given two weeks to live, which I didn’t know about at the time. He lasted 12-and-a-bit months longer than they expected him to.”

They married in at Bull’s parent’s house in Masterton in 1982, with The Chills in attendance. Martyn Bull passed away in June 1983, but his impact on Griffin’s life has been strong. She told The New Zealand Herald in 2013 that he was still the reason for many of her musical decisions. “He’s in my head all the time … it’s not talking as much as a feeling … and when I practise he joins me. He is Mr. Leather Jacket.”

During this time, Griffin became involved in two bands. Her first was the short-lived but almost legendary group, The Cartilage Family, with Peter Gutteridge, Shayne Carter, and Lesley Paris. Roy Colbert’s AudioCulture page on their weekend of glory reveals their story, and Griffin smiles when she thinks about their gigs, especially playing Jimi Hendrix’s ‘Purple Haze’. The idea to include the song in the set was “mine and Shayne’s … if it wasn’t mine, then I jumped up and down very enthusiastically when it was suggested. Shayne [was] mumbling, because he couldn’t remember the words,” she says.

The quartet was short-lived, and she recalls disagreements. “When we did ‘Can’t Find Water’, Peter didn’t want me to play what I played, and Shayne stuck up for me, and said ‘let her play whatever she wants, leave her alone’, and Peter did leave me alone, and I got to make up that bass line, and I think that it really makes that song flow.”

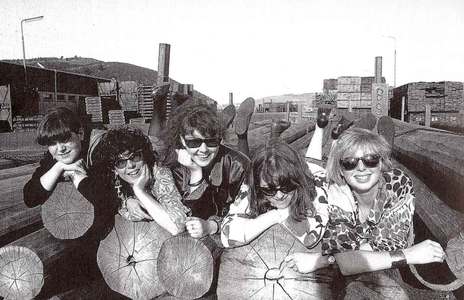

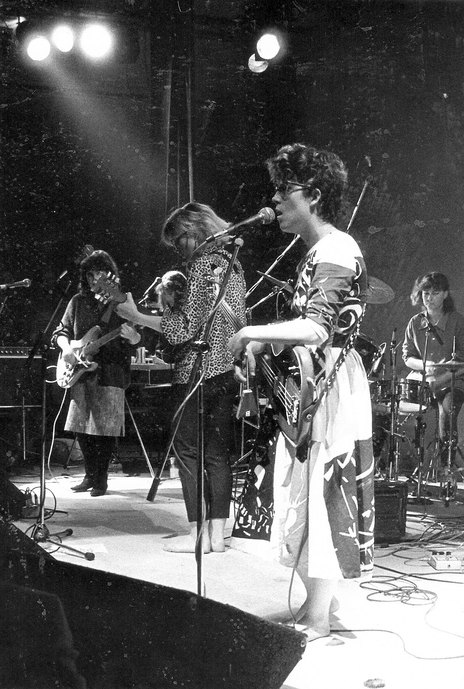

Her other band is truly legendary: Look Blue Go Purple, with Norma O’Malley, Lesley Paris, Denise Roughan and Kath Webster, also became “an item” (her words) at the same time. The band came about after she and O’Malley wanted to play with women.

“Norma and I started brainstorming whom to play with, and she didn’t want to play drums. Lesley was really keen to play drums. Martyn gave her some lessons, and away she went,” she remembers.

“Lesley brought Denise along, and then Norma started saying she had this friend, Kath, who could play guitar … Kath arrived back in town to go to university, then we got started.”

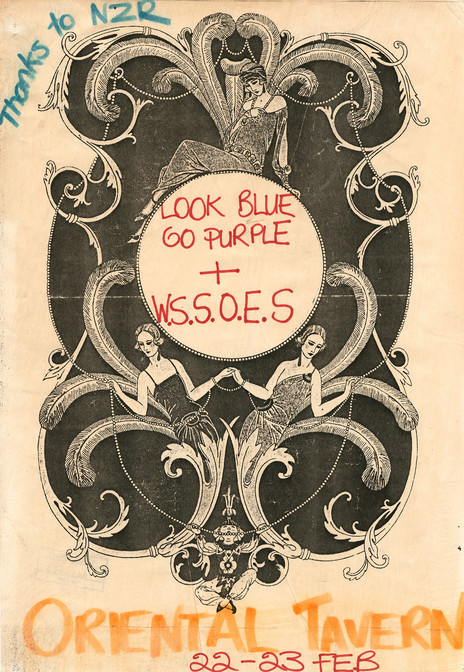

They began practising in the basement of Dunedin’s EMI shop to hone their sound. Griffin has many fond memories of their four years, three EPs and numerous tours together.

“The first time we played, we played at a birthday party at someone’s house in the corner of the lounge, and that was just amazing. I remember the feeling, the room was full of people, and they were really excited. And, playing a weekend at the Empire with Andrew Strang as our support act … at the end of that weekend we had this huge bag of money ... I think we made $1000. Recording Bewitched was just amazing. Making the cover was hilarious … Lots of gig memories.”

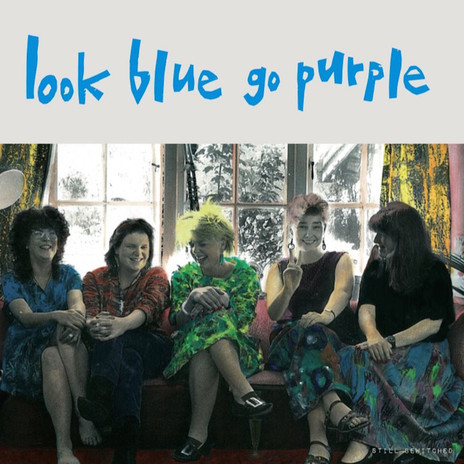

The five remain close, and celebrated the release of their 2017 album reissue Still Bewitched. Griffin’s thoughts on the band have not changed either. “I loved being in that band … I love everything that we did, absolutely.”

After Look Blue Go Purple her focus shifted to family, with son Oscar born in 1988. She also counts a stint working for Roy Colbert at Records Records in the late 1980s and early 1990s as much fun. “Some of those days were completely hilarious … when I needed to get hold of Roy, I would ring his neighbor … it was a very interesting place to work. I let [artist] Ben Webb go through the new pile one day, and he came in the next day and gave me an artwork for [that].”

Her next musical venture was just around the corner – a band called Cyclops.

However, her next musical venture was just around the corner: a band called Cyclops, with friends Bruce Blücher, Peter Jefferies, and Andre Richardson. The band began after she started practising with Blücher, something she hadn’t done for many years. Their initial drummer was Alan Armstrong, who didn’t stay long, and things changed at a birthday party at Chicks Hotel where the band were playing. Armstrong didn’t show up, but Geoff Hoani (of Stephen) and Peter Jefferies were in attendance, and she asked them to play with the band.

“They said ‘sure’ … Peter had such fun that I asked him to join the band.”

They signed initially to Chicago-based label Feel Good All Over for their first single ‘Simpleton’/ ‘Lunar Fall’ (1991), but their attempt at recording an album for the label didn’t quite go to plan, as the test pressing didn’t work. This led to a new record label, New World of Sound, releasing a second 7", ‘Spolcyc’/ ‘Light’ in 1993. Their album, Goat Volume, came out on Dunedin label IMD in 1994 and featured all four tracks from the previous two single releases. Allmusic.com rates Goat Volume highly, noting ‘Lunar Fall’ as a highlight. “‘Lunar Fall’, a wonderful number written and sung by Bull … its soaring guitar would seem to demand U2-style production levels, but recorded in the lovely haze as it is, it sounds much more affecting as a result.”

Griffin doesn’t recall them playing live outside Dunedin, but reports one favourite gig was at The Pitz, where they were the birthday gift. Another highlight was playing with Bailterspace at Sammys, and John Halvorsen complimenting her bass-playing skills. “My head just [expanded], ’cause I think he’s an amazing bass player, and I went ‘so are you’, or something inane like that,” she laughs.

Outside of Cyclops, she recorded ‘Eyes Are the Door’ (the first song she wrote), on David Mitchell’s Portastudio for Turbulence Records’ 1991 compilation Killing Capitalism with Kindness. The lyrics date back to her time in Calgary, but the music was written on Blücher’s Hofner in Dunedin. Another performance captured on glorious VHS in 1991 is of her playing bass with Shayne P. Carter (and Peter Jefferies on drums), for a rendition of ‘Big Fat Elvis’, recorded for the X-Way Vision video, a visual document of Xpressway artists and their friends.

Griffin also performed with Sandra Bell, and played on her album Dreams of Falling, and contributed the song ‘Starfish’, to IMD’s Disturbed compilation. There was also ‘Antarctic’ for Flying Nun’s suffrage-centenary anniversary compilation Shrew’d, which featured her former Look Blue Go Purple bandmates along with many others from the scene. “Lesley rang me one day wanting to know if I wanted to put a song on that,” she remembers. “That was the second song I ever wrote … I’ve completely changed how I play it, it’s a bit long and drawn out on Shrew’d.”

At this point, a sort-of line in the sand is drawn between before and after. Her name changed from Kathy Bull to Francisca Griffin in 1995 when she was a member of a spiritual organisation that she describes as “kind of culty”.

“They had this tenet that you have a name that is yours … and that expresses who you are … so, I was prompted to change my name … at the same time I asked if it would be appropriate for me to have my last name Griffin again,” she explains. “I changed it to Francisca Griffin… it’s been that way for 23 years now. Which, interestingly, is longer than I’ve known all my friends as Kathy Bull.”

She feels like she changed with her name. “I was kind of … ‘militantly changing’ then, but I subsequently realised that really I was just becoming more who I actually am, and maybe the name change helped me do that … for whatever reason, people took offense that I changed my name. I still don’t understand that.” However, returning to her family name Griffin was, in her words, “a good idea”.

Griffin’s return to her muse led to her 1998 debut solo album, the lo-fi Songs From the Sky.

By this time, her younger children Alexander and Gabriel had arrived, and she took a break from music, playing occasionally. “I’d broken up with [their] dad, and started playing music again – realising after coming out of a really difficult relationship that music was the thing … I started doing it again, and I loved it.”

Griffin’s return to her muse led to her 1998 debut solo album, the lo-fi Songs From the Sky on her own label, Oddfish Productions. With funding from Creative New Zealand, which she was awarded on “the strength of a letter and a demo tape,” she recorded the album at Super8 studios with Steven Kilroy. Her live band of Heath Te Au and Tenzin Mullin was augmented by David Kilgour on guitar, keyboards and bass, whom she gratefully credits.

“Without David and Steven’s support, that record wouldn’t be what it is,” she enthuses.

The album was well received, with NZ Musician commenting that the lo-fi production “tends to favour the upbeat, poppier tracks, while the slower songs provide a balance of dark mood often shrouded in plate reverb.” To support the album, she played live, including an Orientation in Christchurch with Cloudboy and Jay Clarkson.

It’s at this point that Griffin’s alternative career as a naturopath comes into focus. After Martyn Bull’s death, she “didn’t stay in that plane of learning herbs,” but went back to study in 1998. “I’ve been a naturopath now for 17 years, and it’s an amazing thing to do and I love it. I’m finding new things out all the time … I’ve helped lots of people, it’s very rewarding, and quite frustrating!”

Hand-in-hand is her well-documented love of her garden. “I’ve always been obsessed with my garden,” she laughs. “It’s very chaotic, sometimes, but aren’t our lives?” Also somehow organically related is her involvement in local politics, being elected to the West Harbour community board in 2016. “We’re advocates for our local community, and without us, as with all community boards all over the country, stuff wouldn’t happen.”

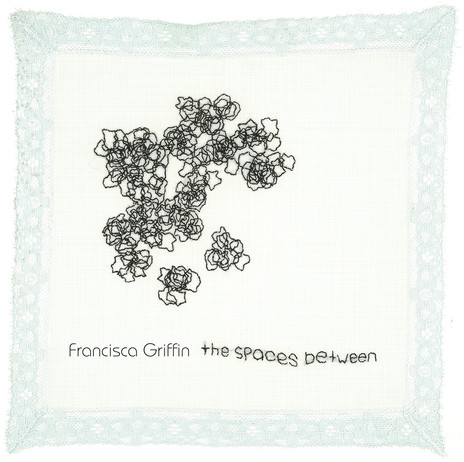

In between naturopathy and politics, there’s been a new album, the spaces between – released in January 2019 on CocoMuse Releases, with artwork by Anet Neutze and Oscar Mitchell. It’s had a long evolution from Easter 2015, when Griffin was persuaded to make another album by fellow musician and songwriter Deirdre Newall, with invaluable support and assistance from Dunedin studio wizard Forbes Williams.

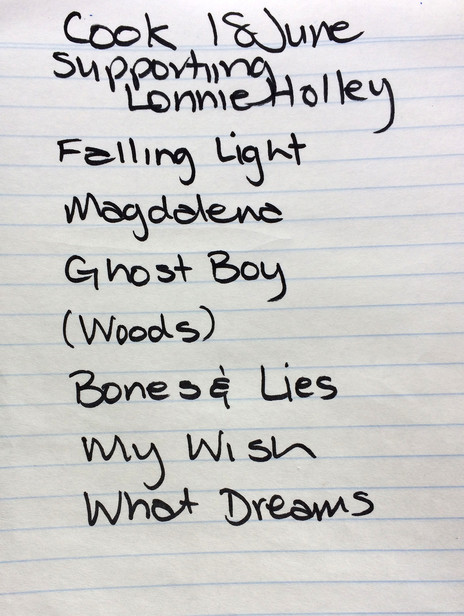

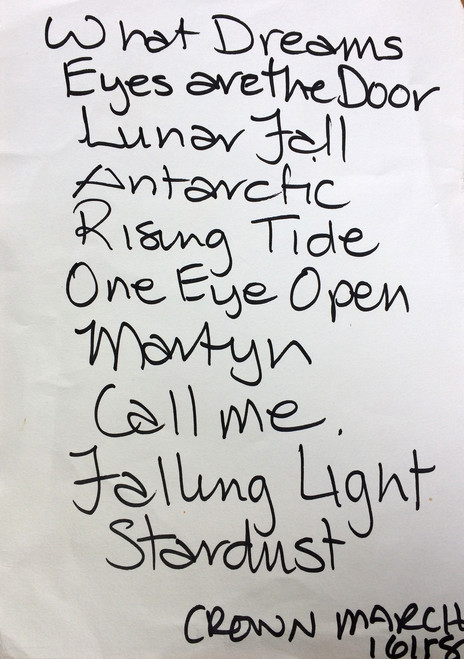

The trio (and son Gabriel) created 10 tracks, spending two years doing overdubs. Songs were written over the last 20 years, with many going through numerous changes, including ‘Martyn’, (about Martyn Bull), ‘Rising Tide’, and ‘Stardust’. There are songs for her son Oscar (‘Ghost Boy’), and Peter Gutteridge (‘My Wish’, a response to his death).

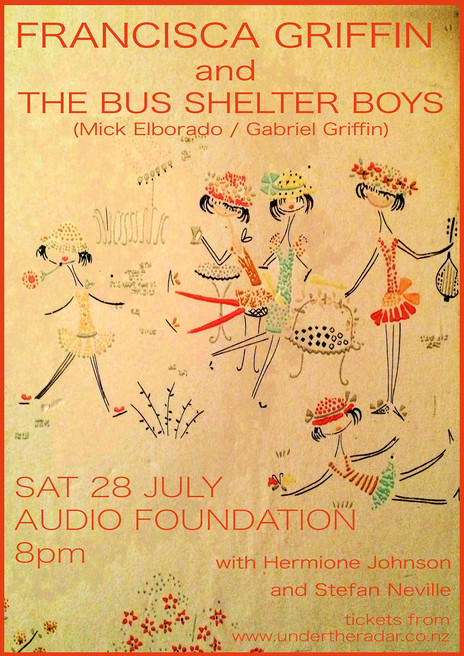

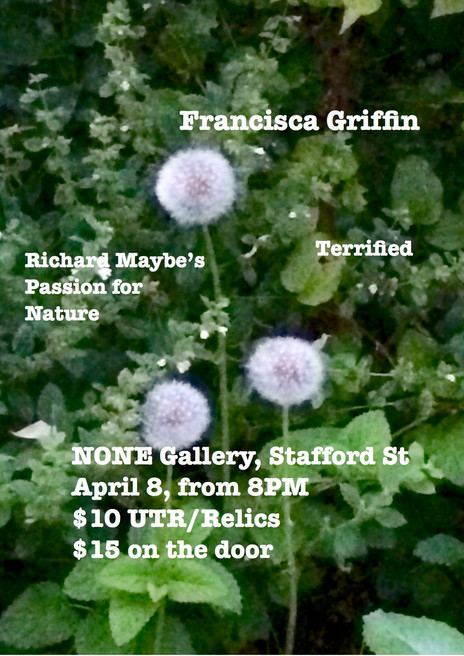

The album launch on 25 January 2019 at The Captain Cook in Dunedin included full band performances on many tracks, with musicians Alan Haig, Deirdre Newall, Alastair Galbraith, Mick Elborado, and sons Gabriel and Alexander Griffin accompanying her. It was a wonderful show, which she followed up with a solo performance a week later, and shows in Blenheim and Christchurch with her band, The Bus Shelter Boys (Mick Elborado and her son Gabriel).

She appropriated their name from a fan who saw and liked their debut performance at Anything Could Happen, the March 2017 Dunedin Fringe Festival celebration of the Dunedin Sound, noting ‘it looked like she’d found her band in a bus shelter’.

“The next time we played at The Crown, I said these are the Bus Shelter Boys, just being a smart-arse,” Griffin says, laughing. “That’s who they are now.” They play in Dunedin frequently but performed in Auckland twice in 2018, including at Whammy Bar, as part of Nowhere Fest – a show seared into her memories.

“It was amazing, my favourite gig of my life so far. Of my life!” she enthuses. “I’ve never had how I felt physically when we played that night … I had goosebumps for all of soundcheck, and the entire set … It was mind blowing. I was as high as a kite when we finished, and I hadn’t had a drink or anything to smoke!”

She continues to conjure this energy in all her work, following her muse and leading a creative life.