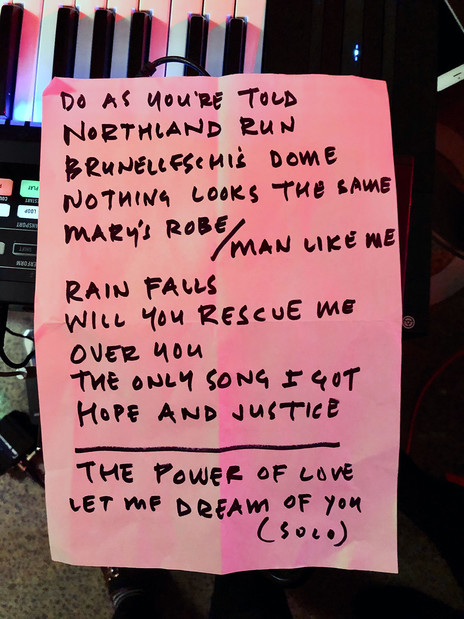

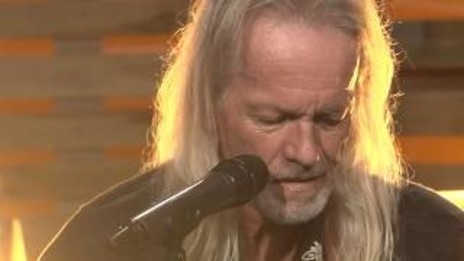

It was greeted with universal acclaim. Across 16 poetic and often lyrically penetrating songs, Lind considered his family and his life, the beauty and sadness of the world, made allusions to art and faith, and took listeners to places which were personal but also universal.

On RNZ’s The Sampler, Nick Bollinger observed, “There’s a tone that pervades this album, something deeper than melancholy. Yet Lind does far more than just hammer on the one emotional note, and if some of these songs find him in spiritual contemplation, others concern themselves with the material world.”

Lind has a deeper well of ideas and imagery than most to draw from.

Solo gained a five-star review in the New Zealand Herald (from this writer) and four stars from Grant Smithies in the Sunday Star-Times: “Across this intimate and thoughtful double album the human condition is examined with great skill,” said Smithies. “He’s a dynamite lyricist”. Pedro Santos in NZ Musician pinned it with “superb”.

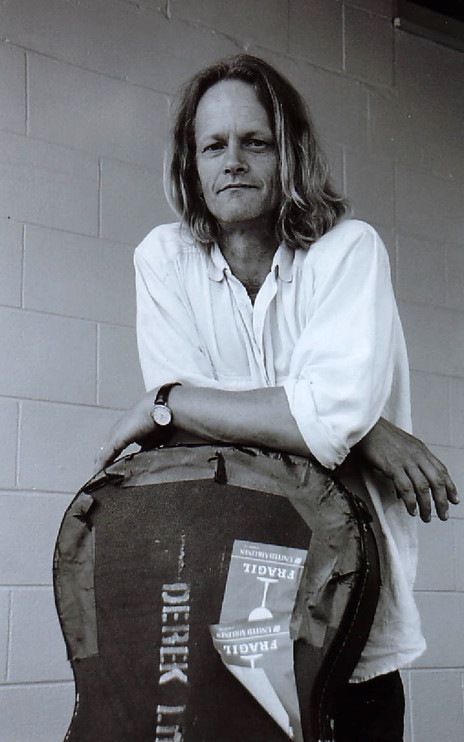

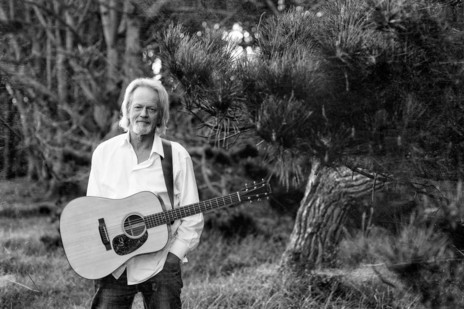

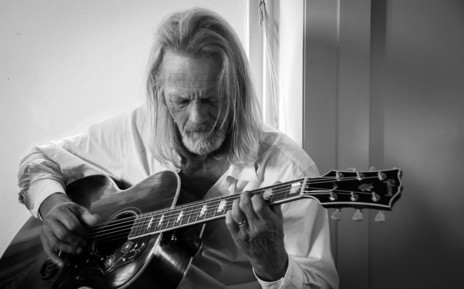

What made Derek Lind albums so special – and Solo was his seventh since Mixed Blessings in 1986 – was that he had a deeper well of ideas and imagery than most to draw from.

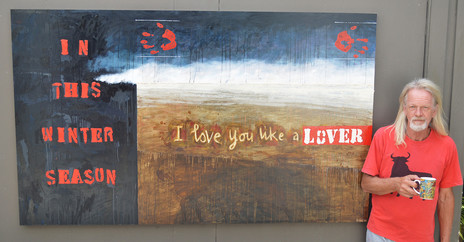

As an Elam graduate (Bachelor of Fine Arts, with painting his major) and a longtime head of a high-school art department, he could reference the visual world – one song on Solo celebrates being atop Brunelleschi’s dome in Florence – as much the songs and styles of his influences such as Bob Dylan, Neil Young, John Prine (referenced on Solo) and Richard Thompson, among others.

In 2015, on the release of Solo, he told me of his early role models in music.

“When I was about 14 years old I joined a record club (some readers may recall them!). The first four albums I ordered were: the Beatles’ Abbey Road, Simon and Garfunkel’s Bridge Over Troubled Water, a Bob Dylan Greatest Hits and Neil Young’s After the Gold Rush. These selections were all rather fortuitous, but as fate would have it, my early role models were not too shabby.”

That breadth and depth of knowledge of music and art honed through study and dedication set Lind apart, and accounts for two music awards and an APRA Silver Scroll nomination.

But there was also another dimension to his work. Lind emerged in the late 1980s from a group of singers and songwriters which included Kevin and Darlene Adair, Dallas Graham, Guy Wishart (who won a Silver Scroll in 1990 and picked up the 2017 best folk album award for his album West by North), drummer/producer Steve Garden, keyboard player Alan Brown, producer Phil Yule and others, many of whom shared a Christian faith.

But theirs was an intellectual and practical kind of Christianity where questioning and spiritual discussion was part of the contract, and the faith manifested itself in work within the community and beyond.

Lind traveled to Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, Thailand, and the Philippines for the relief and development agency, Tear Fund. And in all these places he was influenced by what he witnessed, often the grinding poverty but also the dignity of people in the most dire of circumstances. All of this informed his life, music, and art.

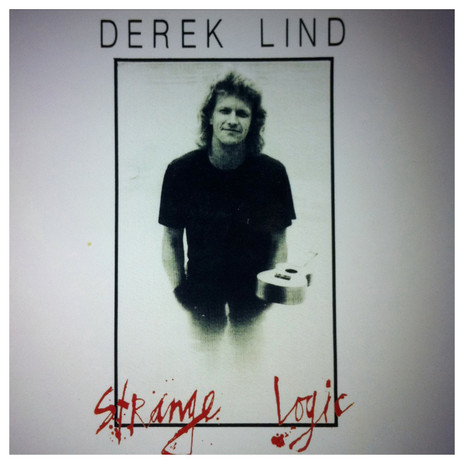

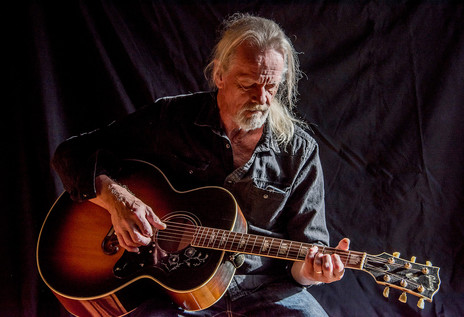

Two years after 1986’s Mixed Blessings came Strange Logic, recorded at Mascot with Yule; Lind playing most of the instruments. But his breakthrough came with the exceptional Slippery Ground in 1990, recorded at Mandrill.

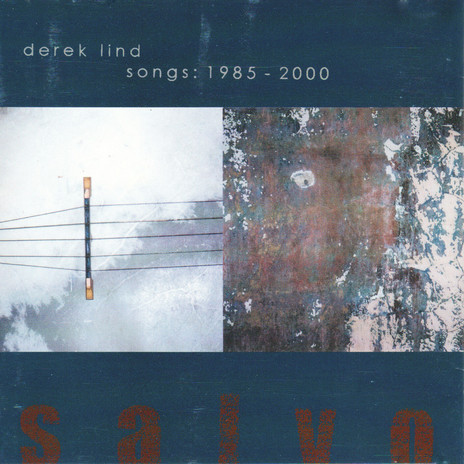

As he observed in the liner notes to his Salvo compilation of songs between 1995 and 2000, “[It] was a bigger exercise in production, longer hours ... [it] was received really well by critics and it was also released in America. Needless to say, no one bought it.”

Slippery Ground is a remarkable album even now, some songs like the brooding title track burn with fury at the profane nature of the world: “Discard the things that are precious, abuse the things that are few, confuse the innocent, dilute the truth ... we turn love into a peep show or a bumper-stickered heart.”

Elsewhere he rails against the consumer society, but also offers precise images from his travels: “There’s a black crow perched on the Tannoy attached to the dome of a crumbling mosque” reports the furiously political Black Crow, written in Dhaka.

He yearns for home and family while away (‘From You’), and for those willing to look and think there were subtle allusions to his Christian faith.

Stations, which followed in 1994, took a different direction: “My most intimate and introspective album,” he described it later.

Integrity, honesty, and a measure of self-aware humour have been among the hallmarks of Lind’s compelling catalogue.

“You don’t always have to sing everything in CAPITAL LETTERS in order to be convincing. I’m also learning that it’s often best to tell your OWN story with as much integrity and honesty as you can muster, trying at all times to make it not sound like therapy!”

And those aspects – integrity, honesty, a measure of self-aware humour – have been among the hallmarks of Lind’s compelling catalogue.

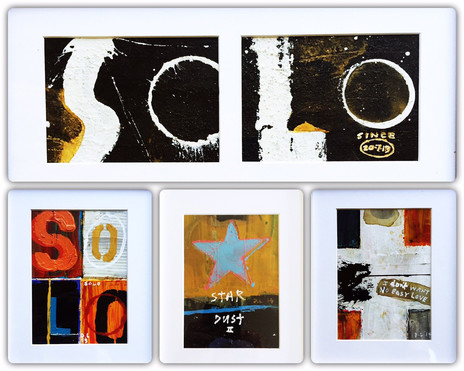

His albums have all appeared on the Someone Up There label which Adair started – loyalty another hallmark – and come wrapped in his own art and photography.

In ‘Ukulele’ on Stations he sings, “This was going to be a painting but it turned into a song, my wife’s father’s ukulele hangs inside the hallway of our home”.

There can be a photographic authenticity and heartfelt quality about Lind’s body of work, but also depths drawn from the faith he holds but questions, and the imagery of art and architecture down the ages.

And joy. Even on Solo – which could easily have fallen prey to the “therapy” he tries to avoid – he offers songs which celebrate life.

Although it would be an ice-cold heart which didn’t melt with a song like ‘Over You’: “I’m walking down a street named Tragedy on the outskirts of a town called Faith. My friends say, ‘You’re holding up, you’re doing well’. But my friend, that’s simply not the case ... ”

Over a career now passing into its fourth decade, Derek Lind has played in churches and prisons, at festivals and in schools, opened for the likes of Michelle Shocked, Hothouse Flowers and Sam Phillips, has played solo shows and is part of the Redemption Highway Collective which sings gospel-blues, and has seen Third World poverty and paintings by Matisse up close.

He has brought all of those experiences – as well as love and loss – to his art and songwriting.

In 2002 on his album 12 Good Hours of Daylight (five stars in the New Zealand Herald), Lind wrote a wry dig at himself on ‘A Bad Song Every Day’. It ended with the following lines: “These days the songs come slower at a more middle-aged pace, and I hope that in time these songs and I will grow old with grace.”