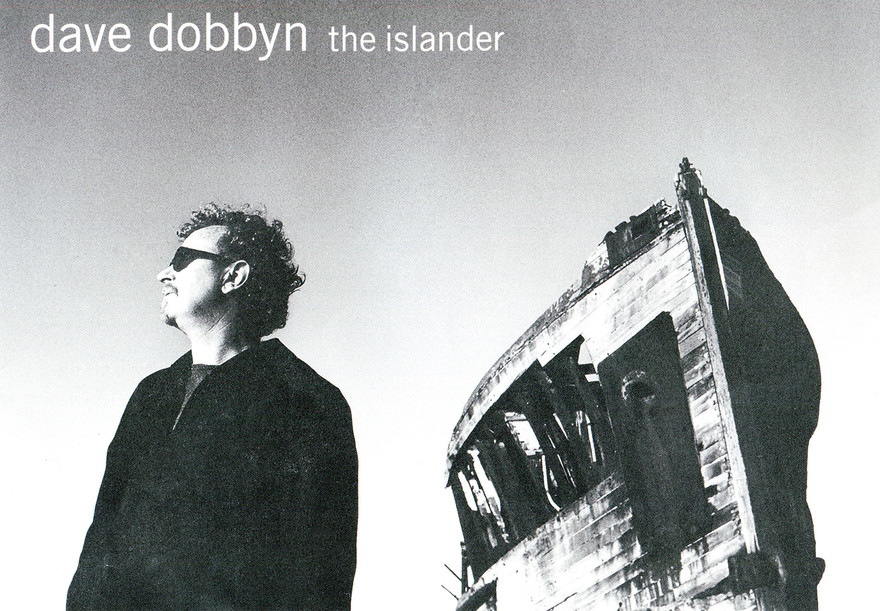

Dave Dobbyn - The Islander (Sony/BMG, 1998)

In July 1998 Dave Dobbyn discussed his songwriting process for The Islander.

“I love talking about this record, because there’s lots to talk about it,” says Dave Dobbyn, just before the release of his new album, The Islander. It has been nearly four years since Twist, and that’s a long time for Dobbyn’s loyal audience to wait for a new singalong anthem.

What has been keeping Dobbyn busy? “Mainly my family. And I have been concentrating on getting better at songwriting.”

What? The man who has written New Zealand standards such as ‘Whaling’, ‘Bliss’, ‘Be Mine Tonight’, ‘Slice of Heaven’, ‘Loyal’ and ‘Language’ felt the need to improve?

“For singer-songwriters, each time you produce something, it’s like starting afresh. A band keeps its personality, but solo performers have to keep reinventing themselves. And you aspire to something each time that is more than you can handle – but is worth aspiring to.”

Dobbyn says that he’s been “working on his musical literacy, getting the competence to match the confidence – and vice versa.” As a result, he’s “fallen in love with music again”.

A couple of recent experiences confirmed to him that he was on track. When the Grammy Awards were on TV, he saw Bob Dylan tell a story about watching Buddy Holly in concert. “Their eyes met, and that was the spark which will always light his fire. I was right with him. Around that time, whenever I put on my guitar, it felt like it did when l first joined a band. I’d forgotten how exciting it could be.”

Then, with his childhood friend and former Dudes cohort lan Morris, he listened to songs by the Texan songwriter Guy Clark. “I loved the storytelling, the eloquence. People can write songs in country music that seem grander, more universal, once they’re delivered. The voice just sucks you in, and they’ve got stories to tell.”

Finding a way of telling his own stories was what Dobbyn found difficult on ‘IThe Islander’ album.

Finding a way of telling his own stories was what Dobbyn found difficult on The Islander. “There’s never been a shortage of melody or music with me. But since Twist I’ve been concentrating on becoming a better musician: inventing chords, looking around, listening more than I ever have. What was agonising about this record were the lyrics. I had a lot hanging around, but they didn’t feel right. Now, I feel a lot fresher about the whole approach of writing songs.”

As a solitary songwriter, says Dobbyn, it’s important to remember to have a good time – and provide one for your audience. But the way he recorded The Islander made it feel like the most collaborative album he’s yet done. Sessions began in Neil Finn’s basement studio last September, when Dobbyn laid down several rhythm tracks with visiting Australian musicians Peter Luscombe and Bill MacDonald. Both are sought-after players in Australia; Luscombe drums in Paul Kelly’s band, and MacDonald has played with Frente! and Neneh Cherry.

It had been years since Dobbyn recorded with a band. “They were chuffed with the way it came out: that the sound coming off the tape was the same as went on.” Dobbyn credits the natural sound to Auckland engineer Sam Gibson (Finn’s Try Whistling This) and the influence of American producer Tchad Blake (Crowded House, Sheryl Crow, Dobbyn’s Twist).

In the summer of 1997, Dobbyn re-entered the studio with Allan Gregg and Ross Burge, The Mutton Birds’ rhythm section that had played on Twist. “From then on, it was plain sailing. I took care of most of the guitar work, though there’s bits of Neil on it here and there. Sam and l did some programming of sounds, a bit of jiggery pokery-but we found there were some layers that just didn’t need to be there.”

Dobbyn then followed Finn’s approach with Try Whistling This. He went to New York. “Neil highly recommended that experience of getting out of town, soaking up another culture, seeing your music in relief.”

Although that worked for Dobbyn, it wasn’t in the way he expected. “I connected with a few musicians, but looked at what it would cost to work there. Then I looked at the job I’d done of getting the music on tape, as a producer-by-default. It became clear that it was fine, that I should hold my head up high, be proud of it and finish it. In the different environment, you could look at your exercise book, your notes and plans and think, “do I really need those overdubs?’

“So I culled a few things out, and it came back to pretty much a rock’n’roll band. Everyone agreed it sounded better and better. Albums – you’ve got to live with them a while to really enjoy them.”

Coming home also provided the title. “I was back only a couple of days, and went up to the Auckland War Memorial Museum with my son Eli. A group of soldiers had just finished an Anzac ceremony, were hugging each other and crying, with their families around.

“On the steps, there’s a brilliant view across the harbour and Rangitoto. I got this incredible feeling of outpost, that I was way out on the edge of the world. And we have been all this time, while fighting other people’s wars. I was aware of how insular New Zealand can be, but expansive at the same time. The only reason people don’t notice us is because we’re a bunch of islands in a sea.

“Nobody gives a damn. That’s the New York attitude.

“But there’s something exotic about this place which we don’t always see because we’re in it. That exotic thing is a real mixture. I came to terms with the fact that I’m a Pacific Islander a long time ago. There’s nothing vaguely European about me apart from the colour of my skin. So I’ve called it The Islander because it’s a stamp of identity.”

Dave Dobbyn on The Islander, song by song

‘Waiting’

The waiting is about frustration. I wrote it in York Street B studio a couple of years back. That chorus came straight away, so it was a chorus sitting round for a long time with nothing to do. I was playing a Supertramp-style Wurlitzer, which set the rhythms. It ended up being a pop record. It’ll be a great one live, but a tough one to sing. I forgot to write the breaths in, as I did with ‘Whaling’.

‘Mobile Home’

I was doing demos in The Lab studio. This one popped out in the control room, when I started playing the chord sequence. I didn’t think too much about it, but instantly made some decisions, like going straight into the second verse after first chorus. I wanted a concise little ditty. It popped out, taking as long to write as it takes to play. It’s about the comfort of your own heart, wherever you’re dragging it around. There’s always somewhere you can plug in. Having an adventurous attitude.

‘Hanging In The Wire’

The title image is of a soldier seeing his buddy on the perimeter wire, hanging there, not being able to do anything about it. It’s a harsh image, but it doesn’t carry on. It’s a reassurance song, a buddy song. What captured me was the middle eight section, it’s like a song within a song. I had fun with the arrangement. It needed to be fairly joyous: out of the dark images you get all sorts of things. Cole’s Porter’s ‘I Get A Kick Out Of You’ gave me the violin line around the melody. There’s a bit of Mott the Hoople about the guitar riff.

‘Be Set Free’

I had the chorus, “be set free”, and was in love with the chord change going to the minor before resolving to C – I must like it, I’ve used that quite a lot on the record. I wanted a verse that was sinewy and wiry, and found a few strange grooves. They reminded me of Neil Young’s Harvest. That’s how I explained it to the rhythm section. But it’s unusual how it turned out. There’s a skip to it. A Wurlitzer plays a reggae thing every now and again. It’s a song about liberation – being set free through some kind of honesty.

‘Beside You’

From the beginning it felt like the ‘Belle of the Ball’ off the Lament for the Numb album, or ‘I Can’t Change My Name’ from Twist. That vibe. There has to be one of those epic ballads. We recorded it about four or five times before we got it. Now, it’s got this swing to it, a pendulum feel to the drums. It’s so good to play acoustic guitar to that. I wanted it to sound Celtic. In earlier versions, I had bagpipes in the choruses, but it was a bit too overt. It would have been a parody, whereas it’s an honest love song. It’s an apology song, a lament. Can’t wait to play it in Ireland.

‘Blindman’s Bend’

A good one when you’re driving in the car. Towards the end it gets quite spooky. Neil was playing guitar, that weird high stuff on the Ebow. He was whacking the guitar, going nuts. I was playing the groove guitar, it’s almost like a ZZ Top guitar without the dirt. It was easy to throw the surprises in at the end. We had various vocal takes, which we left on. It’s about a drive to the west coast when you’re feeling bad, then finding something beautiful there.

‘Standing Outside’

A drunk’s song. I wanted it to be country, but not trad. When I played it to Allan Gregg, he thought it sounds like Pavement, because it’s sloppily played. For most of the recording it was in a key that was too high, I was trying to get a Hank Williams falsetto. It sounded too brittle to me. We brought the key down and whacked it along. I started writing it a couple of years back. I thought, I’ve got to write a loser’s anthem. It’s a Jimmy Stewart thing revisited – It’s a Wonderful Life. It’ll be interesting to see what kind of fan that attracts. Probably people staring at the bottom of their glasses. It’s a parody really.

‘What Have I Fallen For’

A latecomer that really stuck. An unabashed love song. I like that image of two people coming to a table, and there’s nothing on the table, they’re not bringing any baggage with them. To get to that point in a relationship is exceedingly difficult, but worth the journey.?

‘I Never Left You’

I thought it was Lennon-esque, coming from the same place as ‘Imagine’ or something. Piano by numbers. Then the lyrics were really hard. ‘I Never Left You’, the title, is like a cop-out statement: I must love you, I never left you. I’m very proud of the middle eight, it’s like a separate song: it goes on about kids and angels. I wanted a straight-out love song, and was squirming with the sentimentality of it for a while, but it’s found its feet. I like the hooks it’s got, but it’s demanding on the voice.

‘Keep A Light On’

It’s gone through several stages. It’s a small song: “keep a light on for me, I’ll be around.” I first played it with the band as a full-on rock’n’roll song like the Exponents, and that’s pretty amazing, we’ll release that at some stage. But to keep in context with the record, it had to be done in a piano/conversation way. So I recorded it at Neil’s place on his beautiful Steinway. Then I took it to lan Morris’s place, ostensibly to get some string parts on it, which he loves arranging. It was looking expensive so we tried another tack, and added a slide guitar, some Mellotron strings that we put through a Leslie speaker. It came out like a Farfisa. It sits really well with the other tracks. That was one of the red-headed children, as Tom Waits would put it. I hope somebody covers it.

‘Hands’

That la da da da-da bit reminded me of Phil Judd. It was an accident, I was going to put lyrics in, and thought I’ll fix it later. But I kept doing the high nonsense lyrics in the early takes. Then we had six to eight of these things. It sounded like the Teletubbies, but it seemed to be right. You keep all the accidents.

‘One Proud Minute’

I wanted to write a wish-list or manifesto. It started out like a Randy Newman song, just on keyboard. It didn’t end up that way, but I had this idea of beautiful cultural things, paintings, poems, books, all being eroded. I wanted to have a sense of loss through the verse, then have a bit of relief in the chorus. It came together by itself. I didn’t think too much about the instrumentation. That was laid down in the first session with the Australian rhythm section. As soon as the bed was there, Neil came in as guitarist, playing those Keith Richards riffs. Odd for him.

‘Hallelujah Song’

That started as a story, I didn’t know what I was going to do with it. I kind of knew it would be a song. It struck me that doing a vaguely gospel backing would keep you involved in the story. All the lyrics happened in one night, sitting in front of the computer telling a story. That’s how it started. I had all sorts of chords and arrangements, but thought that narrative was the main thing and I didn’t need to mess with it too much. To do a pastiche gospel thing wouldn’t have been right: backing singers, horns, that Leon Russell soul thing. It’s an exorcism of dealing with Catholicism, the imagery we’ve all got. Look what these people do in the name of God. And this is part of me. But you don’t have to believe all that stuff to be able to express what it’s doing to your heart. That was my way of dealing with it, as a fable or psalm. That may mortify traditional Catholics, but it’s good to give it an airing. It is just a story, after all.