AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

Benny Tones

Working from his Organik Muzik Workz studio in Wellington, he’s loaned his attentive ears to works from Electric Wire Hustle, Pacific Heights, Graeme James, Rob Ruha, Iva Lamkum and literally hundreds of other bands and solo artists. Alongside his studio practice, Horton has also worked as a live sound engineer, DJed outdoor raves and nightclubs, and recorded and produced his own well-regarded solo albums, Earth Tones and Chrysalis.

Golden Bay

Growing up during the 1990s in Golden Bay’s Tui Community, Ben Horton was exposed to outdoor rave culture from a young age. “More than anything else, that would have shaped everything to do with me musically,” he says.

By the time Horton was 13, he was listening to reggae, trip-hop and downbeat acts such as Bob Marley & The Wailers, Portishead, Kruder and Dorfmeister, Smith & Mighty and Nightmares On Wax, and attending outdoor dance parties. Something about the expansive feeling of the music was a perfect fit with the lush, upper South Island landscape. Together, these elements created the perfect catalyst to dream big.

Through spending teenage summer nights and days at seminal raves like Entrain (a forerunner to The Gathering), Horton became equally immersed in the futuristic, DJ-driven sounds of trance and progressive house. In his late teens, he realised just dancing to the music wasn’t enough. He wanted to DJ it. “I bought some turntables, started buying vinyl, and got hooked straight away,” says Horton. “It didn’t take me too long to figure it out.”

After starting with progressive house and trance, he developed a taste for disco, Chicago house, French house, breakbeat, and drum & bass. “There was a huge drum & bass scene [nearby] in Nelson at the time,” he says. Hand in hand with DJing, he relocated to Christchurch to study automotive engineering.

Moving to Wellington

During the summers when he returned to Golden Bay, Horton would spend time with good friends, like Jesse Phillips, aka DJ Jesse Jehmal, who was planning to relocate to Wellington to do a basic music production course at The Institute of Animation and Technology (IAT). After some encouragement from Phillips, he enrolled in the course and moved up to Wellington as well. “Jesse [Phillips] is probably the sole reason I’m even doing any of this,” says Horton.

The course was run by Casey Rarere, aka DJ Kase, from the Porirua/Cannons Creek hip-hop crew Hamofide, which suited Phillips and Horton down to the ground. “By this point, we were quite into hip-hop,” says Horton. After Rarere moved on to pursue other opportunities, IAT brought in a new set of teachers, Thomas Voyce and Simon Rycroft from Wellington dub’n’bass group Rhombus, and audio engineer and producer Brett Stanton.

“The first course was more about production and making beats,” remembered Horton. “This version was more about audio engineering. That was when I realised that I was more interested in the sonic qualities of music than the music itself.”

An avid student, Horton learned everything he could during the classes and habitually asked his teachers extra questions at the end of the day. “They were into it,” he says. “They were really glad that someone was that keen.”

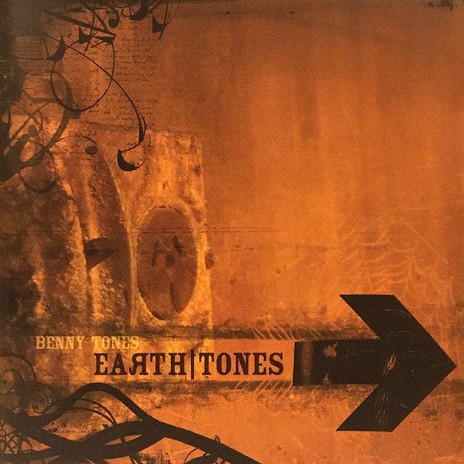

Earth Tones

After finishing up at IAT, Horton began building a production studio downstairs in his Newtown flat, where he wrote and recorded his debut album Earth Tones under the name Benny Tones. At the same time, he took part in an additional three-month production course helmed by Daimon Schwalger, aka The Nomad. “While I was doing the course, we became good friends,” says Horton.

In 2005, Horton released Earth Tones on CD through Schwalger’s Fresh Produce label. Since Schwalger had just finished Quinessence (his fifth album as The Nomad), he asked Horton to tour with him to promote both albums. Over the course of making Earth Tones, Horton worked with a cast of collaborators, including Shanti Costar (of Spartacus R), singer-songwriter Chloe Langley, Aidan Leong (of So So Modern), Thomas Voyce, Jeremiah Ross aka Module, Meagan Chandler and others.

Some of them, like Costar and Langley, were old friends from when he was younger. Others, like Ross, were people he’d met through finding his way into the music scene. “At the time, Jeremiah [Ross]’s music was very similar to what I wanted to create at the time,” Horton recalled. “He had no ego and was keen to get into the studio and play around.”

On release, Marbecks Records described Earth Tones as “A fresh synthesis of cultures, lifestyles, ideas and experiences, all mixed together into a wonderfully atmospheric ambient/downbeat album.” Nineteen years later, however, Horton has some misgivings about the album. “I had a funny relationship with Earth Tones,” he says. “It was incredibly good for me to create it, but I’m not sure if I should have released the first ten songs I’d ever made as an album. I used things like field recordings to make it cohesive, but maybe I should have waited a bit longer.”

Once he had his own recording space, Horton quickly caught the bug for acquiring vintage synthesisers and studio equipment. “I spent every cent I made on gear,” he says. “The vintage stuff was nowhere near as expensive as now, that’s for damn sure, but it was still crazy expensive for me because I wasn’t exactly making much money.” That said, the results he was getting were so good that in 2007, Christchurch funk band P-Bass Expressway approached him about mixing their second album, Snag Bag. That year, he set up his company, Organik Muzik Workz and began to provide paying customers with music recording, mixing and mastering services.

Pacific Heights

Horton’s next major project was working with Devin Abrams, aka Pacific Heights, on his third solo album, In A Quiet Storm (2008). “I recorded all the vocals for that at my studio in Newtown,” says Horton. “We worked with P Digsss, Mara TK, Lisa Tomlins, Ladi6, Aeries, Jdubs, Sacha Vee, and Mark Vanilau.”

Having looked up to Abrams since he first heard him play in Shapeshifter in the early 2000s, Horton took a lot of inspiration away from the experience. “There was a track on the first Pacific Heights EP called ‘Lavenia’,” he says. “I remember hearing [the original Shapeshifter drummer] DJ Dreadford play it [at the Destinations outdoor festival] just as the sun was coming up. Devin [Abrams] was making music I felt on a super deep level.”

While working with Abrams on In A Quiet Storm, Horton met keyboardist, songwriter, producer, and DJ Dave Wright, aka Taay Ninh. “Dave and his partner had just moved back from Melbourne,” he says. My partner knew them and wanted to introduce us. I remember Dave just coming over to my studio to hang out. It was kind of amazing how everything just slotted in together.”

Wright had been playing in the Christchurch/Auckland-based electronic/organic big band Solaa. However, after meeting drummer Myele Manzanza and vocalist/guitarist Mara TK, he started dreaming up a new musical project with them: Electric Wire Hustle.

Electric Wire Hustle

Named after ‘Electric Wire Hustler Flower’ off Chicago rapper Common’s eclectic 2002 album Electric Circus, Electric Wire Hustle were inspired by the blend of hip hop, psychedelia and neo-soul music that was fermenting in the US, UK and European underground music scenes at the time.

Much like Abrams, Wright had a singular focus and vision for the music he was beginning to create with Electric Wire Hustle. “Devin [Abrams] and Dave [Wright] knew how to push music forward,” says Horton. “I was always interested in trying to push the boundaries a little bit. I was never really wanting to create the same sound as somebody else. I was more interested in trying to figure something new out.”

Wright’s vision was partially a product of his experiences playing in Solaa and a fortnight spent attending the Red Bull Music Academy in Melbourne in 2006. There, he had the opportunity to spend time with the unofficial leader of the then-emerging Los Angeles beat music scene, Steven Ellison, aka Flying Lotus, before taking a trip to the US, where he visited producer/DJ Robert O’Bryant, aka Waajeed, at his New York studio.

When Wright returned to Wellington, he was locked in on a rhythmic concept called “Dilla time”. Named after the late, great Detroit hip-hop producer James Dewitt Yancey, aka J Dilla, “Dilla time” represented a combination of overlapping straight and swung (or quantised and unquantised) grooves. “I remember Dave playing me some and telling him it was out of time,” Horton said. “He looked me in the eyes and said, ‘Yeah, man, that’s the point.’ At first, I didn’t understand it, but it didn’t take me long to fall in love with it.”

As well as being fascinated by “Dilla time”, Wright was a huge fan of The Native Tongues, a New York-based Afrocentric hip-hop and neo-soul collective that worked with Bob Power, a multi-platinum record producer and recording engineer. “Dave knew that specific crews used specific engineers cause they knew how to make their records pop,” Horton said.

From studio to sound booth

Once Electric Wire Hustle started recording with Horton, Wright approached him about the idea of coming on tour with the group as their live sound engineer. In the process, he essentially became their fourth member.

“Their sound was really difficult to reproduce live,” says Horton. “It was a huge mix of highly produced and programmed studio elements and live playing. The only way to seamlessly reproduce it was to have me doing the live sound as well because if the engineer wasn’t invested in what they were doing, they could easily ruin the gig by mixing it wrong.”

In 2009, Electric Wire Hustle released their first 12" EP 001 through Japan’s Wonderful Noise Productions before establishing their own label, Every Waking Hour, to release their self-titled debut album in New Zealand later that year. The following year, the UK label BBE (Barely Breaking Even) released it overseas. Quickly, Electric Wire Hustle’s music began to appear on tastemaking US music websites such as Okayplayer and BBC Radio 1 playlists via DJ support from Gilles Peterson and Benji B. “They became far more well-known overseas than in New Zealand,” says Horton.

Over the following years, Horton accompanied Electric Wire Hustle on tour around New Zealand, Australia, Southeast Asia, and further abroad in Europe, the UK and North America. Horton continued to work with the group on their second and third albums, Love Can Prevail (2014) and The 11th Sky (2016), as well as solo records from Manzanza and TK. “I remember laughing when Dave told me we were going to do a world tour because I had no idea where the money was going to come from,” says Horton. “But they made it happen. Those five or six years were a crazy roller coaster ride, and I was very lucky to be part of it.”

Along the way, Electric Wire Hustle shared stages with hotly tipped musical figures of the era, such as Dam-Funk, The Sa-Ra Creative Partners, Jamie Woon, SBTRKT and Sampha. From the outside, it looked like a golden moment, but the shows could be challenging. “For the first full year of touring, the audiences would be looking back at the stage in confusion,” says Horton. “It wasn’t that they didn’t like it, it just took them awhile to warm up to it.”

Chrysalis

While Electric Wire Hustle was navigating the international music scene, Horton continued to spend his time at home, offering his studio services to other musicians and recording his own music. In 2011, he released his second album, Chrysalis, through the Every Waking Hour label in New Zealand. Fittingly, BBE and Wonderful Noise picked it up for overseas release as well. “I think what happened is I realised I’d found the sound I was looking for,” says Horton. “It was trip-hop – on the Kruder & Dorfmeister and Nightmares On Wax side of things – mixed with the Los Angeles beats scene sound.”

At the time Chrysalis was released, I described it in Rip It Up as “an ornately detailed journey of expansive proportions.” Starting with raw, instrumental backing beds he crafted in his studio, to bring his songs to life Horton called on a range of session musicians and vocalists from the musical communities around him. Among them were Electric Wire Hustle, Devin Abrams, Joe Dukie, Lisa Preston, Adi Dick, Future, Sacha Vee, Sam Trevethick (of Shapeshifter), Darcy O’Brien, Ryan Prebble, and Shihan The Poet. “It was amazing to work with so many people I held in high regard,” says Horton. “At the time, people in the scene were just so amped to get in the studio, have a go, and try something different.”

Two years later, Horton gathered up remixes from 30 different electronic music producers and musicians from around the world for a remixed version of Chrysalis titled Chrysalis The Remixes (2013). “What happened was originally, I signed a two-album deal with BBE,” Horton explained. “Not long after, I realised that I wanted to focus on engineering rather than writing my own material, so I asked them if they’d be willing to let me release a remix album to fulfil the contract.”

Stepping away from DJing

As well as shifting his work focus towards audio engineering, mixing, and mastering, Horton also found himself stepping away from DJing after the arrival of Serato’s Scratch Live DJ software in the mid-2000s. “During the Electric Wire Hustle period, I had a few DJ residencies at Wellington bars like Sandwiches and The Matterhorn,” he says. “Serato killed DJing for me, but not in the way you might expect. Once I started using it, I realised how visual the way I DJed actually was.”

Prior to using Serato, Horton would flick through his record bag and be able to instantly identify the right song to play from memory based on how the cover art and record grooves looked. Once he had to scroll through a list of songs in a playlist on his laptop, he found himself getting flustered mid-set. “When I looked at the music as a list like that, I couldn’t see the songs in my head in the same way,” he admitted.

Thankfully, by this point, the recording, mixing and mastering services Horton offered at Organik Muzik Workz were in steady demand. “I think there’s something super special about having access to every single part of a song and being able to steer that direction on a much deeper level,” says Horton. “You have so much control. When I was a DJ, I think I always wanted more control. So getting to shape music on a much deeper level was hugely satisfying.”

Graeme James

In 2013, Horton started working with the then-Wellington-based folk singer-songwriter Graeme James. At the time, James had been building a name for himself as a street entertainer. An accomplished multi-instrumentalist, his secret weapon was using a loop pedal to build up enthralling, multi-layered tunes that wowed audiences. “I saw him go from a busker on the street to a full-time performing musician,” said Horton. “Now, he lives in Amsterdam.”

Over the next two years, Horton recorded two albums of cover songs for James, Play One We All Know and Play One We All Know, Vol II. In 2016, they recorded his first album of original material, News From Nowhere, which entered the Official New Zealand Top 40 Albums chart at No.30. Over the following years, several of James’ recordings, most notably ‘Alive’ and ‘Young Blood’ (covering The Naked and Famous), became viral sensations, prompting him to sign with Canadian label Nettwerk and relocate to the Netherlands in 2018. Since then, Horton has continued to provide James with mixing and mastering services.

Organik Muzik Workz

When I was going through Horton’s Organik Muzik Workz website, I noted that he has worked with around 200 different bands, solo artists, producers, record labels, and other businesses in the last 17 years. Since 2014, some of the more recognisable New Zealand names he’s worked with include Drax Project, Tiki Taane, Louis Baker, Estère, Rob Ruha, Tali, and TOI. That said, he’s always been, and very much remains, willing to work with new and emerging talents. “There’s been a lot of artists that I’ve worked with who were no one when I started working with them, and they turned into something bigger, which is awesome,” he says. “It’s so satisfying to see people succeed in this industry because it’s so difficult.”

In 2017, Horton briefly revisited his own music when the New York/Berlin-based label Airdrop Records released a double A-side 12" from him. ‘Time’ / ‘Maybe In The Stars’ features vocals from Rwandan New Zealand rapper Raiza Biza and Wellington singer-songwriter Louis Baker (under his alias Alby Love). The 12" also included remixes of both tracks.

These days, Horton operates Organik Muzik Workz from a dedicated studio space under his house in Wellington’s Northern General Ward. Having spent nearly two decades working in music, he’s had a side-of-stage (or front-of-house) view of what it looks like when a musician or band starts to break through. In the process, Horton’s learned a thing or two.

“You have to be willing to give everything to it completely,” he says. “Otherwise, you have no chance. You can’t just be like, I’ll keep my day job and try for a couple of years. You might get lucky and go viral, but you might not as well. I’ll always have a lot of respect for the people who actually make it because the journey can be so scary. You have to be able to live a life of high anxiety without worrying too much about where the next pay cheque is coming from.”

Fresh Produce

BBE

Every Waking Hour

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air