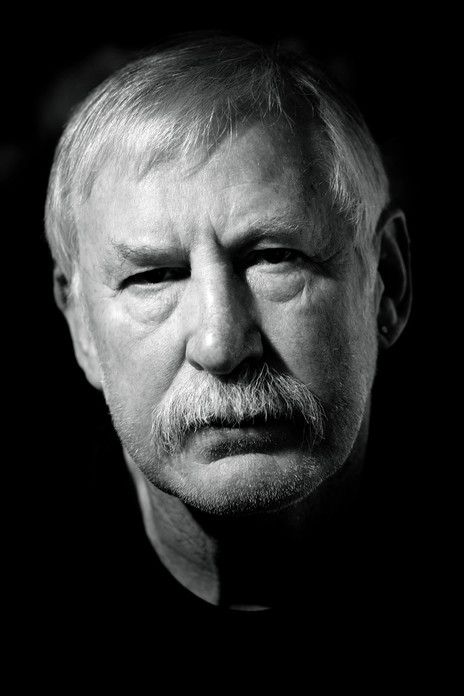

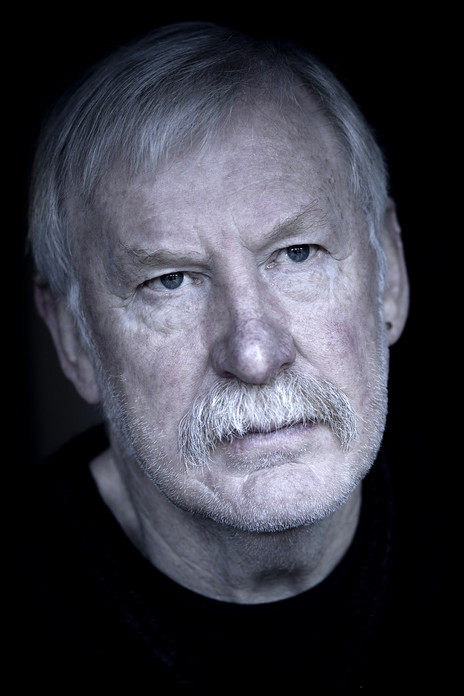

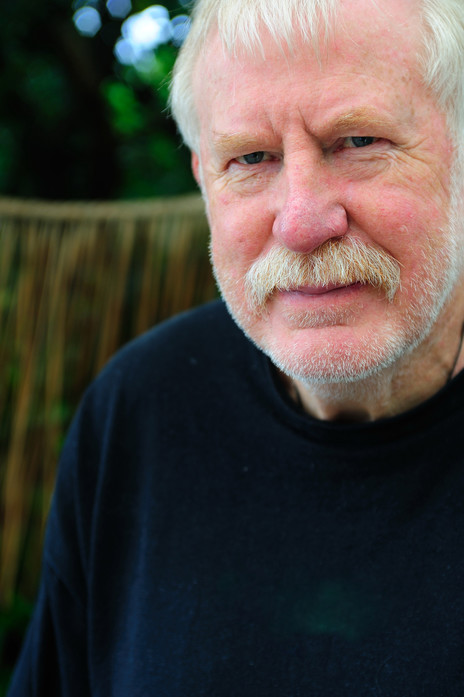

Richard Nunns’ playing of taonga puoro evokes the ancient landscapes of Aotearoa, the voices of its indigenous people, birds, and insects. The shimmering waters, wild winds, and dripping caves, the squawking, chattering and trilling of ngā manu, the depths of emotions of ngā tāngata, the wiri of their hands, the rhythms of the haka and the bending notes of old chants can all be heard in his sensitive performances.

These are ngā reo o te whenua, the voices of the land, that were almost lost forever, were it not for the curiosity, patience, and persistence of Richard Nunns, along with Hirini Melbourne and carver/instrument maker Brian Flintoff.

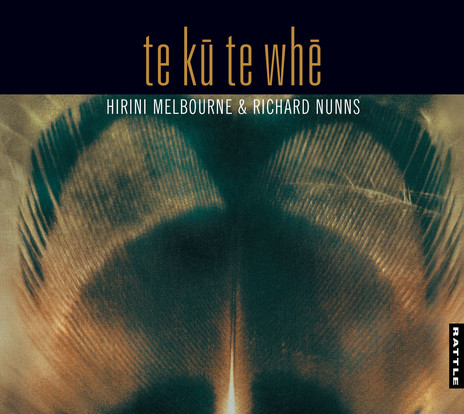

It’s difficult to overestimate the importance and influence of their 1994 album Te Kū Te Whē, the first album of taonga puoro recordings. These traditional Māori instruments hadn’t been widely heard for around 150 years, since missionaries came to Aotearoa.

While a Pākehā man of German Lutheran and Yorkshire descent was an unlikely revivalist of this indigenous music, Richard Nunns’ family background provided excellent training for what lay ahead.

The Nunns family had a tradition of playing in brass bands going back a couple of hundred years. For a time the Gisborne Brass Band’s unofficial name was the Nunns Band, so many of the male members of the family were involved.

“I have this curious reaction to brass bands now, I personally don’t like the ethos. And I’ve never ever been keen on wearing uniforms and so on, so I was a distinct failure there. But there must be something genetically seated there, because every time I hear a brass band, the hair rises on the back of my neck and I get a shiver. And I often will go and watch but it’s not something I’ve ever wanted to be part of.” (1999, RNZ Musical Chairs with Eva Radich)

Richard’s father was a cornet player who widened his musical repertoire into the big band music of Artie Shaw and Glenn Miller, playing dances and balls with his band around the East Coast and Hawke’s Bay in the 1940s, and this was the music that filled the house when Richard was growing up.

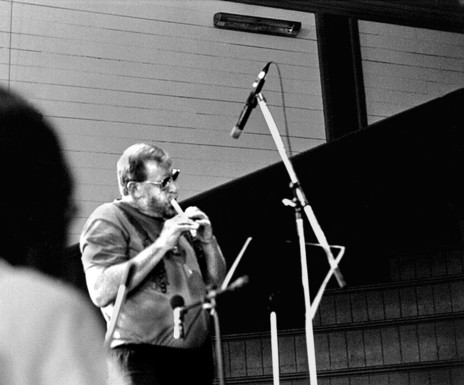

Born in 1945, Richard began on the trumpet aged nine, playing duets with his father, and later with a dance band and the school orchestra. He would eventually put this embouchure (the position and use of the lips, tongue, and teeth in playing a wind instrument) to good use on the pūtātara (conch trumpet) and pūkāea (long trumpet), but through the 1960s he was immersed in the growing jazz scene, playing with people such as Paul Dyne and Jim Langabeer. This improvisatory way of playing would also later feed into his explorations of taonga puoro.

Richard enrolled for teachers college, specialising in music, in Christchurch in 1968, and took up the opportunity to learn the flute. This training gave him more embouchures and avant-garde techniques which later allowed him to realise the different voices possible from the then silent Māori wind instruments found in museums and marae display cases around Aotearoa.

Richard says that he’d noticed these instruments when he was 14, interested enough to cut out an article from the Auckland Weekly News about the collection in the Auckland Museum. The journalist wrote of the beauty of the instruments, and the sadness that they had “long since fallen silent”.

Richard first noticed taonga puoro when he was 14, reading an article that said they had “long since fallen silent”.

The 1965 book Music of the Maori by Terence Barrow says of taonga puoro: (sic) “Modern Maoris have forgotten how to play these instruments, with the notable exception of Mrs Paeroa Wineera of Porirua Pā, Wellington, who learnt the art of playing the short flute (Koauau) when she was a young girl.” There is a beautiful photograph of the kuia, who would have been in her late 70s, holding an ornately carved koauau in front of her. There are a few short recordings of her playing, and an interview from 1961.

Taonga puoro were spoken of as instruments that were present at major rites of passage – conception, during childbirth, for healing and tangihanga. They were used for communication between people, gods and ancestors, “a cellphone to the divine” as Richard often puts it. The practice of playing taonga puoro almost disappeared with the arrival of Pākehā missionaries to Aotearoa. Many instruments ended up in museums and private collections overseas, others were destroyed during public conversions of Māori to Christianity.

Having completed his teaching degree, Richard Nunns moved to Hamilton, and became involved with the Māori community there when he volunteered to help build a marae on the Melville High School campus. He felt intensely drawn towards te ao Māori and made himself useful in whatever way was needed – weaving tukutuku panels, pouring concrete, and sweeping the carving rooms.

“It was an inroad into another way of seeing and being in this country that I suppose never knew existed.”

His early interest in the Māori experience, tikanga, kai, and reo was nurtured by respected leaders and educators such as John Rangihau, Rose and Joe Pere, and Tīmoti Kāretu. Sometimes, being the only man around at school, Richard was obliged to lead the pōwhiri on the marae, with the very basic te reo Māori he had picked up.

Rangimarie Rose Pere is an educationalist and tohuna tipua (wisdom keeper) who Richard became close to at that time. He admitted to her that he had been a professional musician, and that he was interested in knowing about the instruments of the tangata whenua.

“In the nicest possible way, it was as if she never heard the question, she turned away, and I knew enough not to pursue that line of questioning.”

A year or two later, sitting on the porch of the Pere’s house at dusk playing flute, Rose said to him, “You make that flute sound like human beings speaking. Remember when you asked about the traditional instruments? If you are meant to find out, you will.”

He took it as her blessing, “being pushed out on that waka to journey alone.” He understood that gaining the knowledge behind taonga puoro would need patience and humility (whakaiti) on his part.

He understood that gaining the knowledge behind taonga puoro would need patience and humility (whakaiti).

Relocating to Nelson in 1978, Richard began to experiment with making sounds from bones, and trying to glean any historical information on the instruments he could. He was introduced to local carver, Brian Flintoff, who was interested in making art that also had a function. Like Richard, he was Pākehā, and came from a teaching background. Both had been captivated by the stories and mythology around taonga puoro, and they had complementary skills – Brian could create the instruments, Richard could make them sing.

By 1984 there was enough interest in the instrumental music of Māori that a wānanga was held in Te Araroa. Here Brian and Richard connected with the third strand in the group that was to become Haumanu, Hirini Melbourne. A fluent te reo Māori speaker, songwriter and musician, he also had an intense curiosity about these dormant instruments in museum cases.

The National Museum’s collection was brought to the marae at Te Araroa in the boot of a staff member’s car, for people to handle and play. Mutton bones were carved into kōauau, and wooden pūtōrino began to take shape. Haunting sounds started to emerge from the wānanga.

Invitations from around the country started to come to the trio from marae and institutions curious about the music they were making.

Often the sounds triggered fragments of memory, primarily from kuia. “After sessions in marae, kuia would come weeping and crying, and hold you and stroke you and say ‘I remember’.” A few elders emerged who had been taught to play as children, but they hadn’t picked the instruments up for decades.

It was a long process for Haumanu (meaning to revive) to connect the fragments of knowledge, and make reasonable assumptions. The unbroken tradition of mōteatea (chants) gave an idea of the shape of melodies and rhythms. The construction of the instruments themselves meant they were limited to four or five tones, but traditional Māori chant is microtonal, so Richard bent the notes, and fell off the ends of phrases as he heard the singers do.

Sometimes groups would want the musicians to play at wāhi tapu (sacred places) so that the ancestors could hear these instruments again. Richard says that he leaned into responding to the landscapes, and listening to the voices present – “dredging the sound up from the earth”.

He felt he was receiving some spiritual guidance along the way, and played these taonga with prayer-like reverence.

He felt he was receiving some spiritual guidance, and played these taonga with prayer-like reverence.

"How they should be held and how they should be breathed into voice has actually come to me in a sequence of very literal dreams. And I anguished over that for many, many years, and I garnered enough courage to speak to one or two of the old people, mainly women who have acted as mentors for me within the Māori community. And the mere mention of that to them brought the whole body language of relief. As though it explained something to them.”

“I often have the feeling like I’m some kind of conduit or vehicle and occasionally the sense of people standing at my shoulder.”

A musician who Richard later mentored, Horomona Horo, told RNZ, “He went to the elders and sat with them and he would be given challenges and he would go away … but he’d go back and in his humility, in his red head and pink face, he had the perseverance. Throughout his whole career of playing taonga puoro he got flak from both the Māori world as well as the Pākeha world. The Māori would be saying why are you doing our instruments, you Pākeha?... and the Pākeha world saying why do you want to learn the Māori instruments for? So he was able to overcome both sides of the coin”.

In 1990 Richard was invited by Hirini to Waikato University to teach and research taonga puoro, and here the seeds of Te Kū Te Whē were sewn.

“The album took off in a way we couldn’t have predicted,” says Rattle Records owner Steve Garden. “I thought it would appeal to ethnomusicologists and a select group of academics. But people took it to heart, and it was hugely influential.”

The album, recorded in a day and a half, was Rattle Records’ first release, in June 1994. It sold around 12,000 copies, was awarded gold status in 2003, and 25 years later continues to be a benchmark for the sound of taonga puoro. Suddenly, the haunting sounds of the instruments were heard widely, on television, on movie soundtracks, in pop music, and on radio.

“Richard was fearless, and he loved to play – sometimes he had to be persuaded to not play,” says Steve Garden. “He loved to put himself in challenging situations, and had an obsessive aspiration to see taonga puoro contributing to all facets of music culture, from the most free and avant-garde improvised music to the most commercial pop.”

Suddenly, the haunting sounds of the instruments were heard widely.

In some cases the sounds took on some unfortunate connotations. In the 1994 film Once Were Warriors, the pūrerehua was heard as ominous, when Jake Heke’s anger started to flare. On iwi radio on the East Coast, kōauau was the accompaniment to death notices, and some people from the area now regard the instrument as tapu, only to be used at tangi.

Richard was invited on tour with Moana Maniapoto and her band the Moahunters in the mid-90s, and played on her first two albums, weaving taonga puoro through the electronic beats. At the same time, classical composers such as Gillian Whitehead had become enthralled with Richard’s playing, and wrote chamber music incorporating western classical instruments and an array of improvised taonga puoro. He has played with the NZSO and NZSQ, and has recorded albums with pianists Judy Bailey and Marilyn Crispell; an album with The Mutton Birds’ David Long on banjo/electronics and harpist Natalia Mann; and trumpeter/electronic composer Dave Lisik.

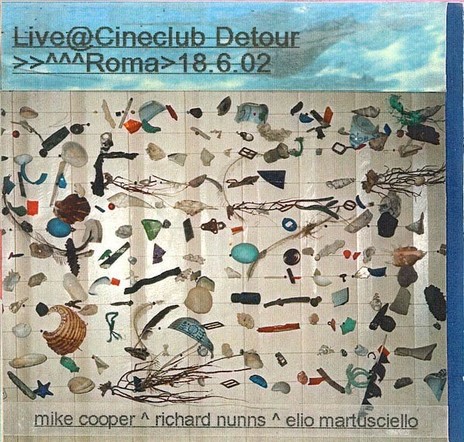

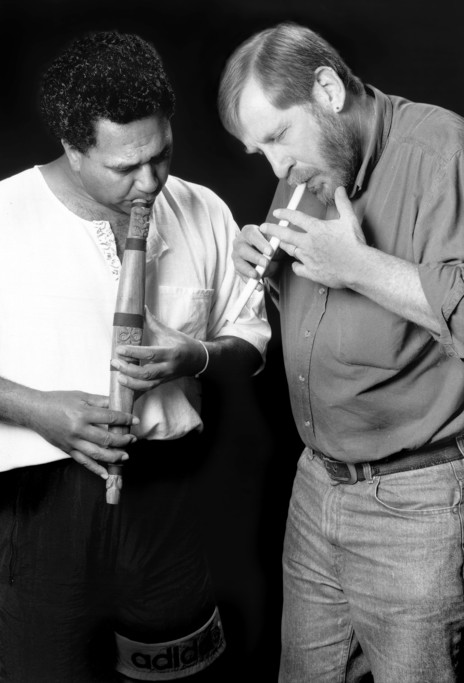

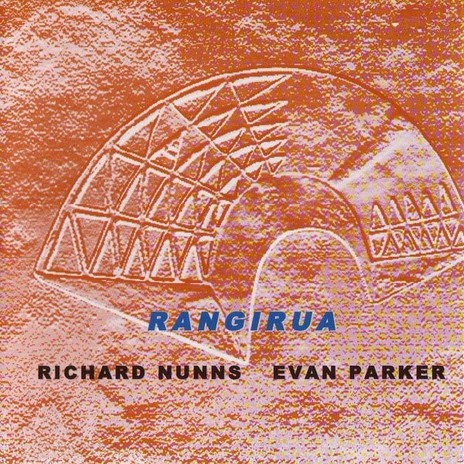

Wellington’s Jazz Festival in 2000 brought Richard back to the jazz realm for the first time in years, playing a concert with influential British saxophonist Evan Parker. Suggested by local free-jazz ringmaster Jeff Henderson, that collaboration inspired many more concerts, and a duet album a year later on Leo Records.

Richard regularly played during the 2000s with improvisational music groups, both local and international, and he evidently loved the conversations between the instruments.

“Improvising musicians were open to extremely close listening and smaller musical gestures,” he told pianist and writer Noel Meek. “These skills are necessary for interacting with taonga puoro which are very limited in their ability to interact. They have such subtle voices. It is a very small sound range and volume with microtonal shifts of the finest degree.”

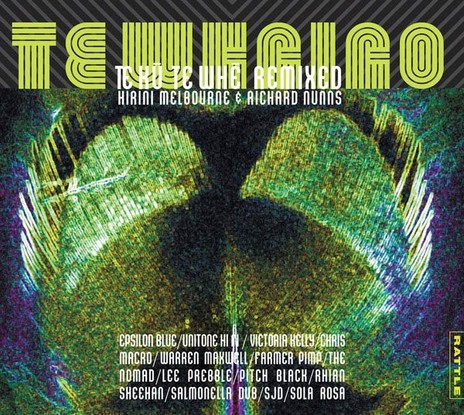

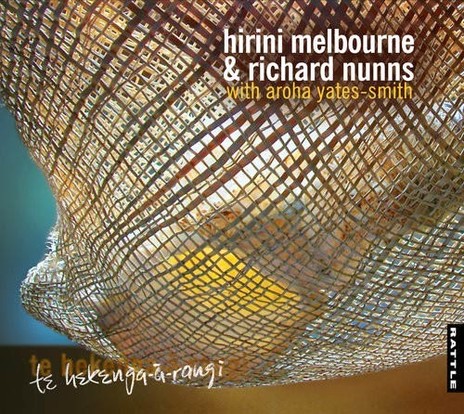

Sadly Hirini Melbourne was diagnosed with cancer, but he and Richard, along with singer Aroha Yates-Smith, made one more album before Melbourne died in 2003. Te Hekenga-ā-rangi is a spiritual album that celebrates the atua wāhine, the goddesses of te ao Māori. In 2006 the original album Te Kū Te Whē was given to producers such as Paddy Free, Sola Rosa, Rhian Sheehan and Warren Maxwell for a remix album called Te Whaiao, spreading the breathy sounds, mixed with electronic beats and textures, onto alternative radio playlists.

Richard was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in 2005. He stayed off medication for as long as he could, and maintained that playing as much as possible was the key to staying healthy. Up until 2014 he continued to record, and tour internationally, creating musical conversations with cultures all around the world. One of his last albums was made in a cave on the Faroe Islands, halfway between Iceland and Norway with a group called Yggdrasil.

“A truly modern style of taonga puoro playing has emerged” – Richard Nunns

One of his favourite albums to make was closer to home, with singer Whirimako Black, in 2011. Te More was an album of mōteatea, with just Whirimako’s rich voice and Richard’s collection of bones, stones, sticks and shells. It’s perhaps the texture that most closely represents the ways the instruments may have been heard in pre-European times, though Richard admits that through all of his free exploration, “A truly modern style of taonga puoro playing has emerged.”

In 2014 he published a book of his journey in the world of taonga puoro – He Ara Puoro, and a documentary was released: Voices of the Land: Ngā Reo o te Whenua, which saw Richard and Horomona Horo wandering down West Coast river beds, making music from the sticks, stones and flaxes they found around them.

Richard has been awarded many accolades including a QSM for services to taonga puoro, admission to the New Zealand Music Hall of Fame, an honorary doctorate by Victoria University, and honorary life membership of the New Zealand Flute Association.

He knew that his quest in reviving taonga puoro would not be complete until there was a new generation with the knowledge, who knew the stories and mythology behind the music, and could make and play the instruments. Players such as Horomona Horo, Warren Warbrick, James Webster, Ariana Tikao, and Alastair Fraser have taken up the mahi of carrying taonga puoro into the future, and there is another generation under them now starting to emerge.

Richard has retired from public life, resting easy on the fact that taonga puoro are not ancient history, but living, breathing, evolving instruments.

He has a couple of kōauau iwi tangata – human bones – in his collection, which he played in wahi tapu such as at the burial caves at the foot of Maungapōhatu in Te Uruwera. In a 2002 article by Peter Beatson, Richard said that he felt it would be a very dignified way for a person to end up, though he conceded that legal obstacles such as the Human Tissues Act would make putting a wish in his will futile.

“Personally, I like the idea that generations of my descendants could have me sitting there on the sideboard in the form of a kōauau. They would be able to say to visitors ‘This is the old fellow. He was a pretty weird old bugger, but this is what he sounded like.’ ”

--

Richard Nunns died in June 2021. Tama Waipara, in his role as co-chair of SOUNZ, wrote: “We will mourn the loss of a beloved artist, musician and friend, Richard Nunns. His passionate exploration of te ao pūoro is iconic and has made a lasting and memorable impact.

“His participation, celebration and love of Māori music alongside the late Dr Hirini Melbourne will forever sit as a rich contribution to the continuum of our ongoing musical tapestry in Aotearoa. We extend all our aroha to Richard’s whānau and friends at this time and say thank you for exciting the air with sounds to cherish and remember. Moe mai rā e te rangatira.”

Music scholar William Dart commented that, with Hirini Melbourne, Richard “opened our ears and hearts to the world of taonga puoro ... A charismatic performer and collaborator, he created a sonic garden that others would continue to cultivate across so many musical genres.”

--

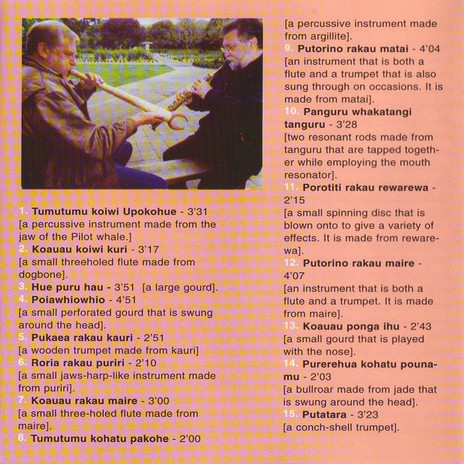

To listen to audio examples of individual taonga puoro, visit He Ara Puoro (A Pathway of Song), a collaboration between Richard Nunns and RNZ, in which Richard plays and begins to describe the many traditional Māori instruments in his collection.