There’s one undeniable truth about Jaz Coleman that makes his detractors seem rather harsh: he really has done it his way, succeeded against all odds.

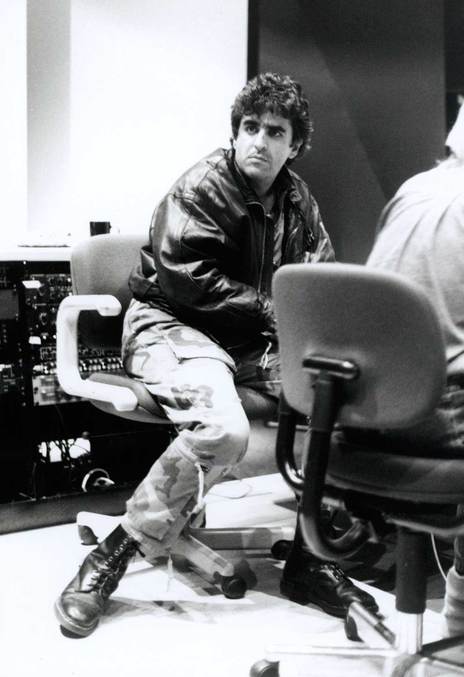

Often mocked by the press for his full-throttle, obsessive character and his eccentric beliefs, there’s one undeniable truth about Jaz Coleman that makes his detractors seem rather harsh: he really has done it his way, succeeded against all odds, never compromising his distinct vision of the way things should be.

Jaz Coleman is an Anglo-Indian who heard almost no rock music during his formative years.

“I was brought up listening to Wagner and European composers, and then everything from Stravinsky to Shostakovich, to more modern avant-garde composers, and then to Can and other bizarre rock music – there wasn’t any rock and roll in there,” he told me in 1992. But being a teenager through the tumult of the punk era, Coleman tuned into the energy and formed his own band, Killing Joke, in 1978.

Inspired by contemporaneous outfits like Joy Division and Public Image Ltd, they found an early supporter in PiL’s John Lydon. But their own sound, unveiled to the world on their self-titled 1980 debut, was a savage meld of punk rock, hard rock and dub influences, blended into a sonic assault that perfectly matched its apocalyptic imagery. Coleman’s performance style was pure shaman, a zombie-eyed voodoo man, and the group’s rhythms were so repetitive and tribal that they could be trance inducing. The group’s commercial peak was achieved in the mid-80s with the single ‘Love Like Blood’, but manifestations of the group have existed fairly consistently, adopting an electronic guise in the mid-90s, and a raging metal shape in the 21st century.

But Killing Joke is tangential to this story. Or are they? In 1992, Coleman told me: “We just won a three million lawsuit against Nirvana. They admitted that they ripped it off. Everyone knows that they ripped it off. It’s a good thing for New Zealand because I’m investing it in this country, right?”

What he’s talking about is the Nirvana song ‘Come As You Are’, a huge hit that same year which took its riff and guitar sound straight from the Killing Joke song, ‘Eighties’. So it’s possible that Nirvana ended up inadvertently jumpstarting Coleman’s NZ investments, including York St.

Let’s flash back, however, to the point at which Coleman reckons his fascination with New Zealand began.

“I’m 14 years old and I’m at Cheltenham Town Hall and there’s this band called Be Bop Deluxe playing,” Coleman told me in 2013. “The way I used to get into all these gigs in my hometown was I used to help load the gear in the afternoons, and this is when I met Charlie (Tumahai, later of Herbs and the Once Were Warriors soundtrack). He was really kind to me, and the first person to really educate me about Māori culture.

“And then I came to New Zealand in 1985, married to a New Zealander, when ‘Love Like Blood’ was on the charts, and I bumped into Charlie at Mandrill studios, and he remembered me as a school kid.”

“I thought ‘time to start fishing and just forgetting about life’, and of course I ended up building York St recording studios, which went three times over budget."

— Jaz Coleman

Then in 1993, after years of litigation with former band members, Coleman emigrated here. “I thought ‘time to start fishing and just forgetting about life’, and of course I ended up building York St recording studios, which went three times over budget. I didn’t make one day’s wage out of York St, but ye gods, I met the most incredible people. My induction into Māori studies really began at that point, the lifting of the tapu on York St. It was an incredible time.

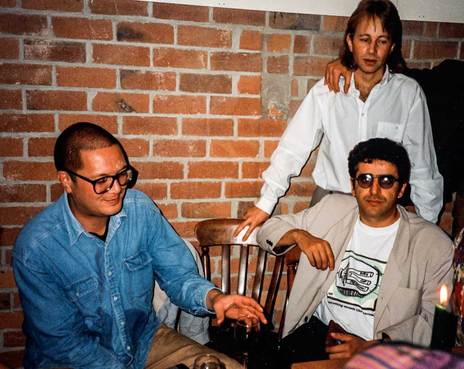

“I promised the people that organised the lifting of the tapu that I would produce one Māori artist completely free of charge, and this was Emma Paki, an artist I truly believed in. And the other person I met at the opening was Hini, and when I heard her sing I was just blown away. They were my two golden girls, and of course there was Shihad. They did the first seven days of York St – prior to this – we tidied everything up in a basement in my place in West Auckland. We did three weeks there and they were tight as razors, and we slammed them into York St, and I think the backing tracks went down in two or three days including overdubs. We had a day for vocals, and the rest was spent rushing mixes for the Churn album. And then Emma Paki’s ‘System Virtue’ was the day after, and we did the whole thing in a day, and both did really well and defined the artists as such.”

And then Coleman met composer/conductor Peter Scholes on a soundtrack commission featuring the Auckland Philharmonia, and he has been a colleague and mentor ever since. “I don’t think people are aware of how many records I’ve done with Peter and the London orchestras and the NZSO and the Auckland Phil.

“I had my own agenda of a Māori/Pacific renaissance, which you can see in a lot of my expressions at that time, for example, Pacifica with the New Zealand String Quartet. And then I didn’t want to embrace anything Māori until I’d studied the culture for a few years and familiarised myself with all the tonal instruments that most Kiwis aren’t aware of, and Hini was my introduction to this and my teacher, and of course Hirini Melbourne. And so I was permitted to have a vision into a pre-European Māori world because when Hirini came to the studio with a couple of other musicians they brought all these instruments, and just started to play, and I’d never heard sounds like this. It was an incredible privilege that I think has been denied most New Zealanders.

“And the other thing about 1993 was I recorded my first symphony with the NZSO, and six weeks after that it just went like dominos. I’ve done more classical recordings than I’ve done Killing Joke records, and I’ve never stopped Killing Joke. None of that would have happened if it hadn’t been for the NZSO and getting my break with the Auckland Phil in becoming Composer In Residence. You have to bear in mind that I’d only just got my passport, so I was going at breakneck speed: studio, orchestra, string quartet, and then I went straight to the London Symphony Orchestra and took Peter Scholes with me. Peter is such a great conductor, and one of my all time heroes.”

“When I started York St, Willie Jackson came to me and said ‘Uh, they all love you this year, but watch your back next year bro! Ha-ha-ha!’ Boy was he right!

— Jaz Coleman

It didn’t all smell like roses in his adopted country, though. “When I started York St, Willie Jackson came to me and said ‘Uh, they all love you this year, but watch your back next year bro! Ha-ha-ha!’ Boy was he right! And I experienced that tall poppy thing. And it was so ugly. There’s only room for one or two big fish in a small pond. Didn’t I learn that! It got really ugly. I stood my ground, but one of the things I never mastered was … I’ve never made a penny out of this country. I’ve lost money. But the people I’ve met have been worth those sums of money to the power of ten.”

Another glitch was recording with his own band in his own studio: “I went into the studio with Killing Joke and we paid absolutely top rate, because my partner at the time charged me the international rate to get into my own studio, and I then had the problem that the guys in Killing Joke are smokers, and this is a no smoking country, and they wouldn’t even do the session unless they were smoking, and they kind of ended up trashing my own studio.”

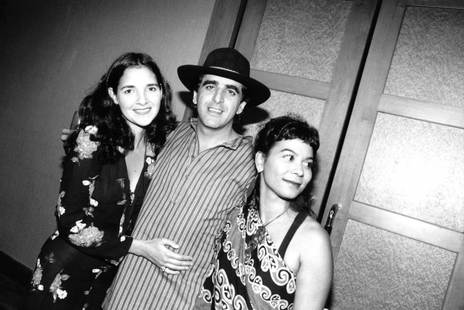

He mentions Emma Paki, whose career was virtually ruined by devastating wrong turns. “When I think of little Emma Paki, she’s one of my great regrets, because we did so well with ‘System Virtue’, and then her manager said ‘oh, we’re not doing it with you, we’re doing it with someone else.’

“She’s a great talent and I still believe she has fantastic songs ahead of her because of what she’s experienced in her life. She’s a vulnerable, beautiful person, and I just wish I could have done more …”

During my first interview with Coleman in February, 1988, he was already hawking a classical score that he said was written about New Zealand. “I would like a university orchestra to premiere it over here. I’m prepared to put the money towards conservation. The rest can go to hell as far as I’m concerned. I like the land and I like animals. I don’t care much for human beings.”

His classical scores have reflected an obsession with the land, and especially the island he lives on for part of the year, Great Barrier.

His classical scores have reflected an obsession with the land, and especially the island he lives on for part of the year, Great Barrier. But why this fascination with a remote island, and living in a house with no electricity or phone coverage?

In 1982, Coleman’s reputation as a rock weirdo was cemented when he “disappeared” to Iceland, where it was reported that his studies of the occult had led him to the belief he would survive the impending apocalypse. Great Barrier is, in effect, a more recent reiteration of that theory.

In 1988, Coleman attempted to explain. “My sideline is a study called Geomancy. I’ve done studies on the Ley-line principal, and the earth energy and magnetic energy, and I’ve done a lot of experiments for the last nine years on this.”

At the time, he was working on a book about the subject, and read me a section: “The most significant progress in the earth sciences was made in Iceland after a series of traumatic experiences where I was actually able to apply information received. Some four years later, I found myself surrounded by an environment providing ideal conditions for the furthering of my work in geomancy. This was some 12,000 miles away on a remote Pacific Island.”

In line with Coleman’s studies, his belief is that humans will inevitably fight until they destroy the world, or around “93 percent of the global population. The surviving seven percent will be distributed between government fallout shelters containing sophisticated eco-systems and small islands of people scattered across the under-populated regions of the southern hemisphere.”

In 1992, he was singing the same song:

“I studied the parallels in mythologies, and the holy writings and they all talk about an island situated at the end of the earth that will survive the great combustion. Throughout the years I’ve given very different interpretations to this mythos. So I went to Iceland first to study the mythos, and then I ended up here. And this is where I believe the place is.”

Which fits in nicely with the thematic content of Killing Joke’s music (no love songs, natch), and where Jaz Coleman has made his sanctuary, for when he’s not performing internationally with his band or holding classical posts in cities like Prague. I just hope he’s at home when the big one goes off.

Ironically, Shihad singer Jon Toogood says their latest album, recorded at York St studios with Jaz Coleman (the first he’s done since their debut), is “sounding like the soundtrack to the end of the universe.”