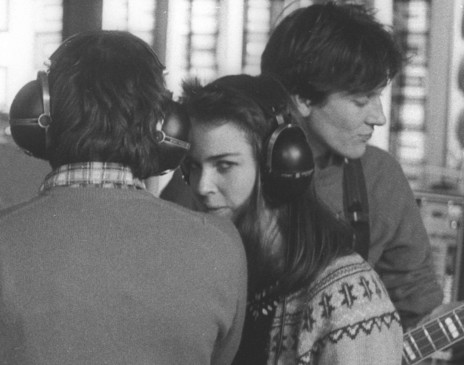

On stage, she was one of four musicians keeping the maelstrom together

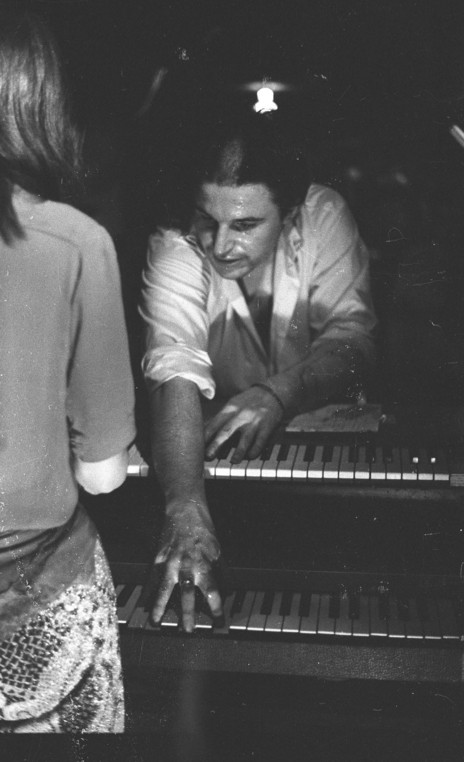

Keyboardists were also rare in that gap between the Scavengers and the synths that emerged after Jane’s last chord decayed at Toy Love’s finale. In a band in which every member was idiosyncratic, her keyboards stood out: strong rhythms in the left hand, busy pop motifs in the right. She played them not as beds but as a lead instrument, as essential and unmissable as a guitar. They added a sense of pop and fun to the mercurial and often dark theatrics of Chris Knox, the powerful toms of Mike Dooley, the sawing, gnarly chords of Alec Bathgate, and Paul Kean’s loping, leading bass. Roy Colbert described Toy Love as “The Stooges with Beatles melodies” – they had all the edgy drama of punk with a sophisticated pop ear, and a quick wit that could react to the room.

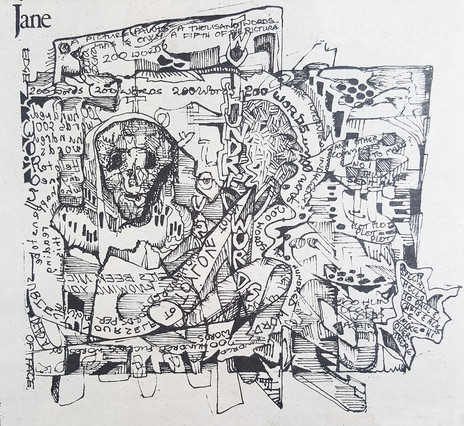

Toy Love was also visually aware: the on-stage broken TV set stuck on static was a clue that almost every member was a graphic artist. Although Knox’s talents became a big part of his persona, that was mostly after Toy Love. While the band existed, they recruited the best freelancers – among them Colin Wilson, Terry Hogan, Joe Wylie – and Jane. When the band’s self-titled album came out in 1980 – sonically disappointing to them until the 2005 remix – it was “back covered” by Hogan, “inner sleeved by Chris, and front covered by Jane”. When Rip It Up’s two-issue spinoff paper Rip It Up Extra came out, the band members were given 200 words each to write “Toy Love by Toy Love”. Jane’s response was an artwork, “worth 200 words”.

Like so many pop musicians, Jane did time at art school – then left quickly. Born in the UK in 1957, while her father was doing post-graduate study, she grew up in Lower Hutt, one of eight gifted children running riot in a rambling old house full of artwork by the whole family. (A younger sister, Julia, would emerge as Jessica in Shoes This High.) The Walkers’ parents were conventional on the outside, but natural bohemians: Jim was a surgeon and raconteur who, after hours, was a snooker champ and effortless boogie woogie pianist. Jeanette, a violinist, had a subversive wit also conveyed in her oil painting fantasias (a late theme was orchestras of escaped zoo animals). It was like Quincy Jones married Jacqueline Fahey: ours was one of many local families that found the Walkers an exciting place to visit.

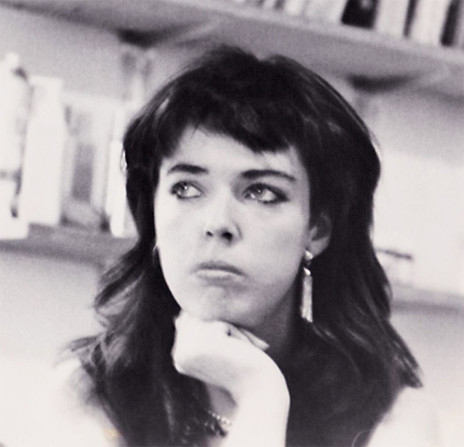

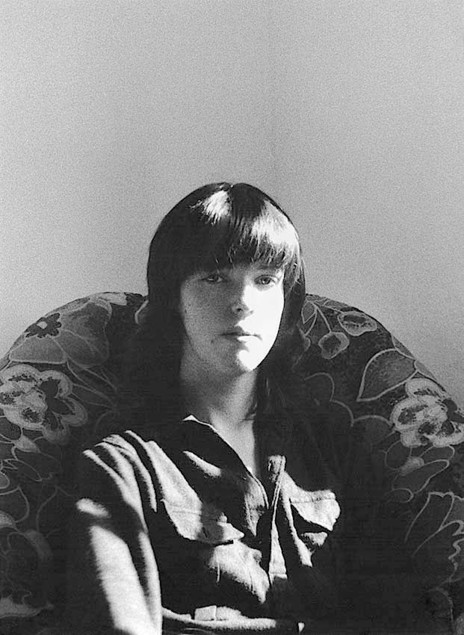

As a teenager Jane’s flair stood out: she was assertive in style and manner

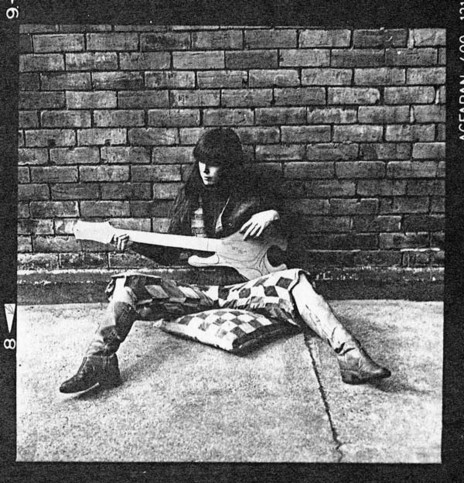

As a teenager Jane’s flair stood out. With long, long auburn hair, she was assertive in style and manner, and had a confidence honed by years kicking about with her older brothers and their friends. She learnt classical piano from local legends Sister Henry and Florence Fitzgerald, and an awareness of Bach and Mozart informed her pop playing.

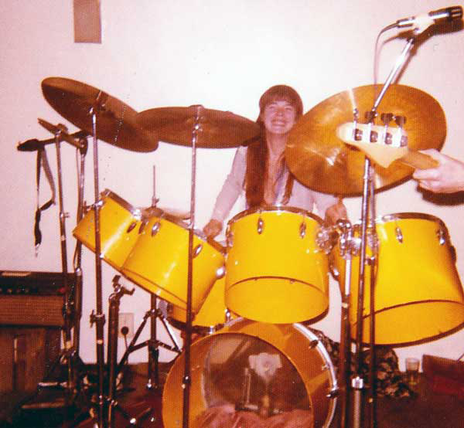

Taking off to Christchurch to get involved in music in the mid-1970s epitomises her individuality. She began drumming for the Basket Cases and the Detroit Hemroids; her partner Paul Kean played bass: when they joined up with the leftovers of The Enemy, the combination created that mix of punk and pop that Colbert described.

When the Toy Love album was reissued in 2005 as Cuts, along with the posthumous Live at the Gluepot, Jane was largely responsible for the creation and design of the Toy Love website. She wrote an eloquent, upbeat memoir that quickly covers a lot of ground: her musical contribution (described almost analytically), the exhilaration and exhaustion of the 19 months Toy Love toured constantly (playing more then 500 gigs), the surreal and Spinal Tap moments, the camaraderie with each other and their fans. It describes better than any observer could the psychic experience of actually being there, making music while being swept along by a cultural king tide in a southerly.

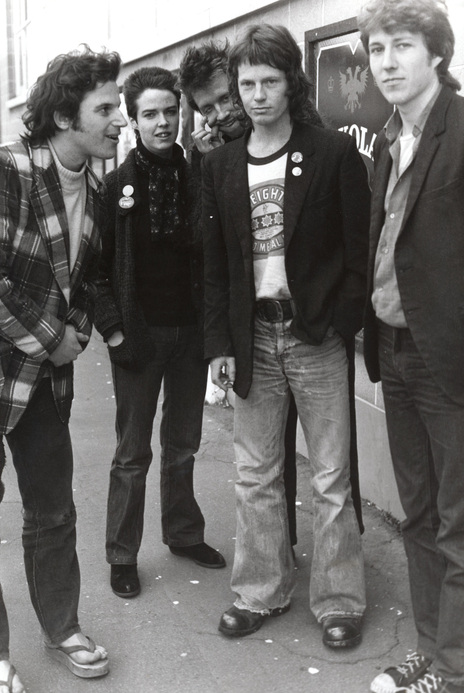

But there were observers, keen observers who knew immediately that Toy Love was something else. With the Suburban Reptiles fading, and Propeller a couple of years away, one of them was Simon Grigg. He remembers The Enemy arriving in Auckland from Dunedin, almost “as aliens” in September 1978. There were “a dozen or so (if you include the crew and partners which you must) out-of-place bodies who were quickly absorbed into the city and then went about changing it forever. That accelerated substantially when the band mutated into Toy Love at the end of that year and 1979 was the year that the now clearly Auckland band – albeit one with no Aucklanders in it – was central to the growing and thriving inner-city post punk community.

“It was a relationship of hundreds of equals but some were more equal than others and Toy Love had a slight aura of royalty about them from day one. That aura varied from person to person: Chris was always a little scary and aloof, Alec was a something of a quiet mystery, Mike – the powerful drummers’ drummer – was universally liked and people just wanted to hang out with him. Paul and Jane, a unique couple, were recognised as musically important not only to Toy Love but to the wider music scene, given the way they added an almost psychedelic pop element to the once-jagged Enemy sound. It was widely copied and very influential.”

Forty years on, the steamy, chaotic Saturday afternoon gigs at Parnell’s Windsor Castle still stand out to Grigg. These were not normal gigs, they were bands and audiences playing together “in a big fluid social event. Chris spent as much time in the crowd with his long mike lead as he did on-stage and members of the crowd were often on the stage.

Simon Grigg: “Jane’s playing and presence made TOY LOVE accessible to a wider audience”

“However, my one over-riding memory of those afternoons is the way we, as in a dozen of us who never missed it, would stand to the side of the stage and watch Jane Walker lift that crowd with her keyboards, always with that strongly focused smile that let us know that she knew why what she was playing mattered and took great joy from that. And it mattered, too, that she was the pivotal female musical element whose playing and presence took Toy Love away from boy-land and made the quintet so accessible to a wider audience. Oddly, I’d always taken it for granted until now, but in very large part, Jane was why one of the most important New Zealand bands of all time mattered as they did and still do.”

Kerry O’Connor, then working at Record Warehouse, also sees Jane’s contribution as crucial – but unacknowledged. “She was a seminal influence on girls realising they could play an integral part in bands. Jane had a huge and significant part in girls joining and playing in bands, not as a token female and definitely a signal not to be taken lightly. A heavyweight – I feel she didn’t get enough recognition for the part she played.”

Graphic artist Terry Hogan managed to persuade his employer WEA (NZ) Ltd – the Hawaiian-shirted home of the Eagles – to sign the band. He remembers Jane as “so smart and forthright, and always with a keen sense of humour and a ready laugh which I can still hear now. As the keyboardist, she contributed crucial colour, drama, and a distinct rhythmic element to Toy Love’s music, which would’ve sounded very different without her.”

After Toy Love’s whirlwind 19 months – which Andrew Schmidt describes evocatively and astutely in their AudioCulture profile – Jane Walker remained involved in music in New Zealand and the UK, but comparatively under the radar. Her memoir on the Toy Love site mentions returning to Christchurch with Paul Kean in 1981, playing in Thanks to Llamas with him and Robert Scott, and doing a lot of sound mixing, “especially when the Dunedin bands came to town”. She spent the mid 80s in Wellington, playing with Naked Spots Dance, the Jellymen, “and lots of doodling with all and sundry.”

Exploring musical modes was “strangely liberating after playing classical and rock’n’roll”

Jane was mostly drumming, “but also fell in love with the piano again”; she learnt to improvise and explored musical modes, “strangely liberating after playing classical and rock’n’roll”. She began playing bass, and was part of a group called Uranium Orchids. With two of the band, she moved to London in 1987; they mutated into Static, playing “nasty industrial weirdness”. Their 12” single ‘Enter’ was made Single of the Week in Melody Maker, “which meant something in those days”.

Remaining in London for 25 years, Jane worked as a graphic designer, including a long stint at the multi-media company Vinyl Solution, whose record label had signed Static. She continued to play music as time allowed, including “a return to good old rock’n’roll organ” with London psych/garage band The Purple Gang.

Jane returned to New Zealand in 2013, shortly after Toy Love – following the hearty reaction to its reissue programme – received the legacy award at the Vodafone New Zealand Music Awards. She kept a low profile musically but reconnected with old friends from many scenes and eras. She remained proud of Toy Love, which she said was always – and remained – a cooperative. On Toy Love’s website, she described the band’s dynamic:

“Our seemingly disparate combination of personalities, influences and styles was bound together by a passion for music, and an intense ‘don’t give a fuck what anyone else thinks’ attitude. Although the consensus was democratic, individually we were anarchic, each took responsibility for their own musical contribution and no one told each other what to play. A healthy disregard for fashion and contrivance meant you’d never catch us wearing matching outfits either.”

After a battle with cancer, Jane Walker passed away on 11 October 2018, in Auckland.