AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

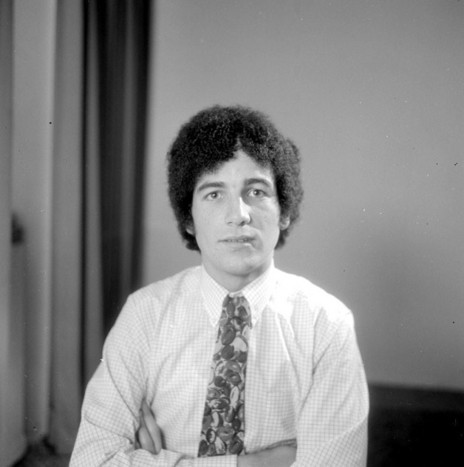

Chris Parry

Having been asked by his boss at Polydor Records to check out punk rock, Parry became hooked on the vibrant new sounds. He wanted to sign the movement’s central London groups The Clash and The Sex Pistols, whom he plied with booze, racked up on the company credit card.

But dragging his more immediate superior to a Clash performance at Chelsea College of Art in October 1976 ended badly when one of the audience threw a bottle at Joe Strummer, the group’s singer and guitarist.

Strummer thought the antagonist was Parry’s boss and abused and pushed him. That was the end of that. Parry remained frustrated he hadn’t signed The Clash or The Sex Pistols or landed the distribution deal for the more eclectic Stiff Records. He got The Jam instead (as recommended by Shane McGowan), by offering them so little money to sign that record company management couldn’t object.

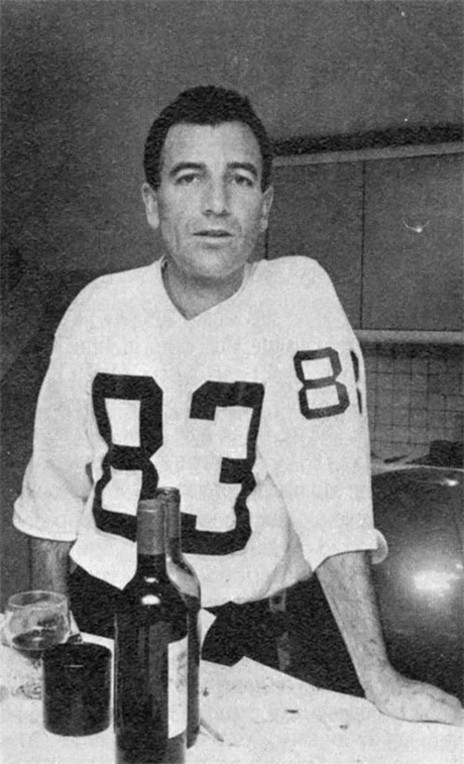

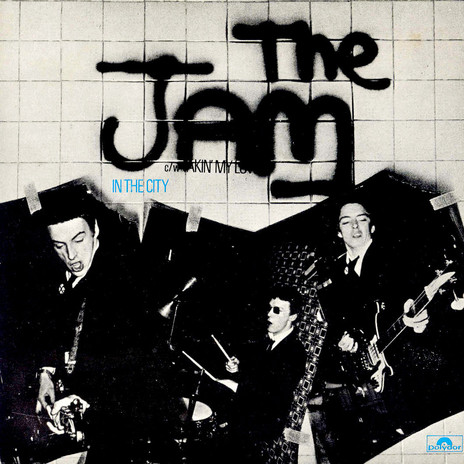

Modish punks fronted by the stylish and tetchy Paul Weller, a teenager already writing enduring songs with punch and resonance, The Jam were a south east London group from Woking. They must surely have rung a few bells in the head of the former 1960s pop star from New Zealand.

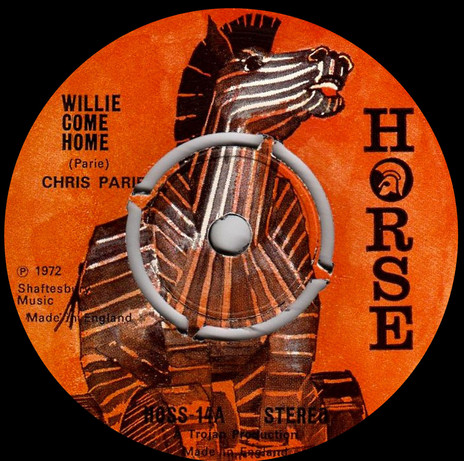

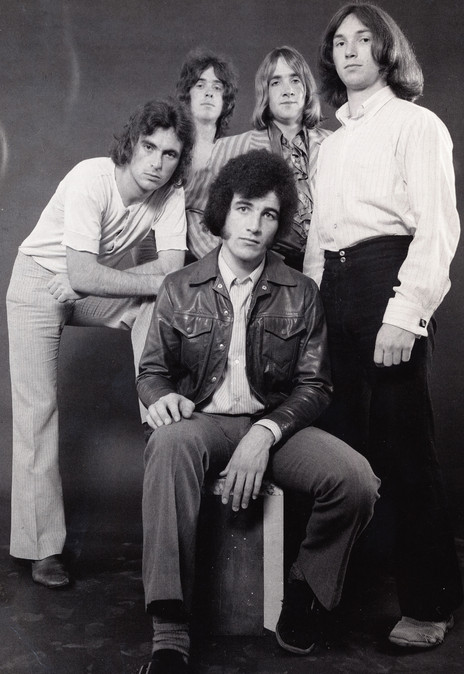

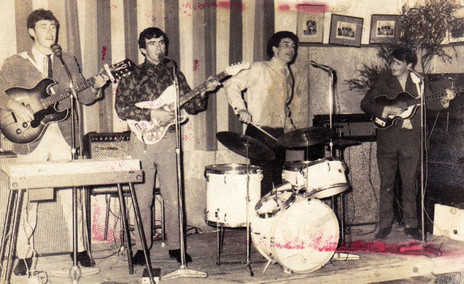

Parry had been the drummer in a string of Upper Hutt beat and R&B groups before peaking in Wellington’s The Fourmyula, chart regulars in New Zealand with a bunch of infectious group originals including ‘Come With Me’, ‘Nature’ and ‘Otaki’. Writing their own songs was important to the group who recorded entire albums of band compositions and an early concept LP.

Bypassing Australia, The Fourmyula headed for London in 1969 where the cutting edge sounds had an immediate and profound influence. Returning to the old country again in 1970, they changed their name to Pipp and recorded the then unreleased album, Turn Your Back On The Wind.

When his Wellington group turned for home one last time, Chris Parry lingered, and disillusioned with music, the former Philips Electrical management trainee enrolled at the College of Printing and Distributive Arts to study marketing and advertising.

Emerging into the workforce in the midst of an economic recession, Parry put his grievances with the music industry aside and joined Phonogram Records under New Zealander John McCready, the label’s international manager.

A move to A&R (artist and repertoire – the department that signed and developed groups) put Parry in the same room as former Upper Hutt schoolmate Terry Condon. A switch to Polydor Records soon followed.

Parry signed The Jolt, The Jam and Siouxsie and the Banshees to the label.

Parry signed The Jolt, The Jam and Siouxsie and the Banshees to the label. He went one step further with raw Scottish R&B punks The Jolt and The Jam by producing their early records with Vic Smith. Captured at Stratford Place Studios, The Jam’s In The City was a minor hit in 1977. The Jolt’s single ‘All I Can Do’ fell short.

Chris Parry recorded two more minor hits for The Jam with July 1977’s ‘All Around The World’ and ‘This Is The Modern World’, the title track from their second album. He’d been helping out with the group’s management alongside Weller’s father John, but soon left them to it, his desire to produce a Paul Weller solo record unfulfilled.

Building on the group’s early promise with the double-sider, ‘David Watts’ b/w ‘A Bomb In Wardour Street’, Parry recorded two more tracks for All Mod Cons, The Jam’s third album and the record that finally demonstrated the trio’s broad talents with a wider mix of song styles and moods.

When the NME Readers Poll of February 1978 placed The Jam’s All Mod Cons as No.1 album, Paul Weller as No.2 songwriter and The Jam as second best group, the trio’s future looked secure. The Jolt’s self-titled debut album failed.

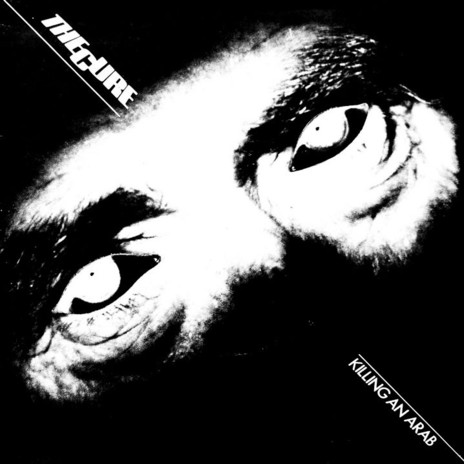

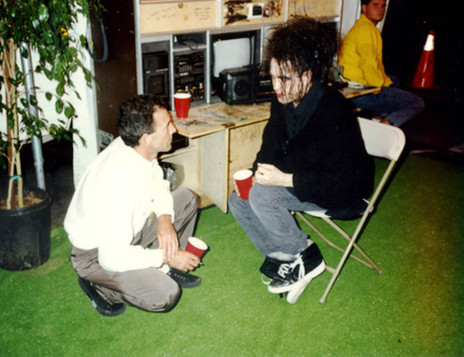

With thoughts of his own label banging in his head, Chris Parry inserted one of those fateful demos into his home tape deck in September 1978. One recording in particular stood out, a song called ‘10.15 on Saturday Night’ that quickly pricked up his ears and was chased immediately by ‘Boys Don’t Cry’. Parry had his band at last and they were called The Cure.

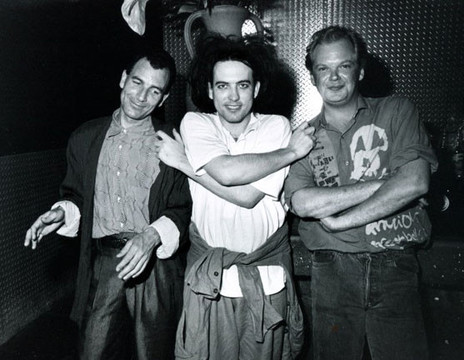

He rang them the following day. The Cure came over to his office at London’s Morgan Studios for a beer and a laugh while Parry outlined his plans for the group. They were an interesting bunch, with singer, guitarist and songwriter Robert Smith, bass player Michael Dempsey and drummer Lawrence “Lol” Tolhurst – and there was a good feeling in the room. Parry signed on as manager.

The first Cure song to hit vinyl proper was ‘Killing An Arab’. The controversial track emerged on indie label Small Wonder Records in December 1978 with Chris Parry as the uncredited producer. It was only a temporary fix. Parry had plans for a label called Fiction Records.

Polydor Records then softened the blow by allocating Chris Parry £80,000 for his own imprint.

Having been passed over for a deserved promotion, Polydor Records then softened the blow by allocating Chris Parry £80,000 for his own imprint. All he had to do was deliver three albums a year. With the post-punk community booming, there was plenty of rising talent to choose from. Fiction’s first three releases over 1979 and 1980 were Michael & Miranda by The Passions, Beat That! by The Purple Hearts, and The Cure’s Three Imaginary Boys.

The Purple Hearts were an east London mod group with a punk pedigree who formed in June 1977 as Robbie Hackett and The Sockets. “Obviously we think of ourselves as mods, and that’s like a state of mind, but it don’t mean we gotta sleep in our mohair suits. We don’t wanna be tied down by an image. We’d rather be thought of as a group for teenagers, for anybody,” singer Robert Manton told NME on 3 March, 1979.

Chris Parry produced the band’s September 1979 single ‘Millions Like Us’ b/w ‘Beat That!’, capturing the sound of the London’s nascent mod scene that was being heard regularly at Bridger House, Music Machine and the Marquee. ‘Frustration’ was the second Purple Hearts single in 1979, chased by ‘Jimmy’ on Beat That!’s release in 1980. The Passions peaked with the Parry produced ‘Hunted’ but missed the charts with Michael & Miranda. Both groups were released from the label.

In 1979 Parry also found time to produce Patrick Fitzgerald’s ‘All Sewn Up’ and new R&B act Back To Zero’s ‘Your Side Of Heaven’. Even stranger was ‘I’m A Cult Hero’ by Cult Hero, an ad hoc studio group formed around Frank the Postman with 13 other drunk people. The joke was to make the unknown Frank a cult hero, so they put him on the cover of the recording of a song they couldn’t get done as The Cure.

The following year Parry added Billy McKenzie and Alan Rankine’s The Associates to his label.

With The Cure’s Three Imaginary Boys a minor chart hit in the UK in May 1979, Parry, who was managing, publishing and recording the group, put them on the road. Following dates in the United States and the band’s first full European tour, the touring trail led the group to New Zealand in July 1980.

British punk and post-punk groups had been conspicuous by their absence on New Zealand’s live circuit, despite their records becoming increasing available.

Parry, a regular visitor home over his long career, accompanied The Cure for the seven-show excursion, taking in Auckland’s Mainstreet and Hamilton’s Founders Theatre in late July and Palmerston North Opera House, Wellington Town Hall, Christchurch Theatre Royal and Dunedin’s Regent Theatre in early August. The support band was Auckland’s Lip Service.

The Australasian label for The Cure and other acts on Fiction Records was Stunn Records (distributed by CBS Records in New Zealand and Seven then EMI in Australia), founded by Parry’s old friend Terry Condon on his return to New Zealand.

Stunn had an early hit with the combined single of The Cure’s ‘Boy’s Don’t Cry’, ‘Jumping Someone Else’s Train’ and ‘Killing An Arab’ which hit No.25 on the NZ Album Chart in February 1980, 46 places higher than the band had managed with the song in the UK the previous year. The album from which it was plucked also settled into a higher chart placing in New Zealand, a pattern that continued with many of The Cure’s subsequent releases.

But that was already history to The Cure. They had a new LP out in New Zealand in July (released April in the UK), the Parry-produced Seventeen Seconds with its evocative linear single, ‘A Forest’. There was a new band line-up on the record with Simon Gallup replacing Michael Dempsey and Matthew Hartley joining on keyboards.

RipItUp’s George Kay caught up with Robert Smith on tour at Dunedin’s Pacific Park Motel, with Chris Parry in the room next door. Smith told Kay the new album was written in a week while on tour with Siouxsie and the Banshees.

The earlier single, ‘Jumping Someone Else’s Train’, had been “written as a reaction to the mod thing at the time, which was really funny, and also as a reaction to the ska and 2-Tone fashion which has become facile. I like The Specials, but Jerry Dammers hates what’s happening. It wasn’t a deep song just an observation.”

Given the fact that Fiction Records released bands from the mod revival, it’s important to note just how quickly sounds were evolving after punk. Surely a 1960s guy like Chris Parry must have noted that the move in his own productions from beat to fast R&B to mod pop (The Jam) to psychedelia (The Cure) and UK soul (The Associates) echoed that of his own teen decade.

In an earlier RipItUp interview Robert Smith joked with writer Jeremy Templer about nicking his manager’s Fourmyula albums.

Certainly The Cure themselves were aware of Parry’s musical past. In an earlier RipItUp interview Robert Smith joked with writer Jeremy Templer about nicking his manager’s Fourmyula albums.

The Cure’s live set for their Australasian tour (recalled by Chris Parry in Live Gigs That Rocked New Zealand by Bruce Jarvis and Josh Easby, 2010) was “all of Seventeen Seconds, ‘10.15 Saturday Night’, ‘Fire In Cairo’, ‘It’s Not You’, ‘Another Day’ and ‘Three Imaginary Boys’, ‘Killing An Arab’, ‘Boys Don’t Cry’ and ‘Jumping Someone Else’s Train’.”

Following the New Zealand shows, The Cure headed for Australia to complete the 40-show tour. In March 1981, RipItUp readers voted The Cure as the best live tour of 1980 with ‘A Forest’ and Seventeen Seconds also strongly represented.

The Cure was back in New Zealand in late July 1981 just over a year later after touring Europe and the UK. This time they had a No.1 NZ album in Faith and a Top 30 single, ‘Primary’, to flog.

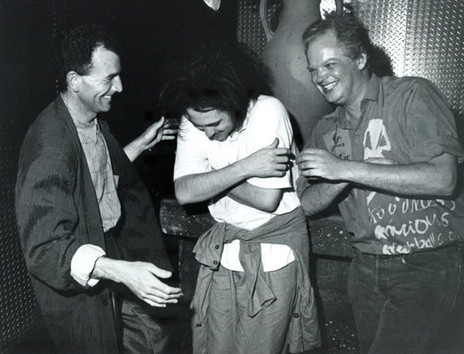

Stunn Records boss Trevor Reekie recalled the first days of the band’s return in NZ Musician. “The Cure had arrived the night before and we introduced them to the industry at an informal ‘lunch’ (liquid/ chemical) at the Rumba Bar in the afternoon. I don’t know how the band were still standing! Robert Smith is an incredibly hard person to get to know or even converse with, and that was a big part of the enigma that he projected on stage. They were very English, aloof and ‘cool’ when it was ‘cool’ to be English and aloof. Lol was dead friendly with both feet on the ground. Simon always seemed to be off somewhere else!”

After two nights at Auckland Town Hall on 31 July and 1 August, The Cure headed south to Palmerston North. in August 1981 In Touch editor Gary Steel noted that their show in the city’s new indoor stadium arrived two days after the Springbok Tour passed through and that The Cure played to “a more mainstream crowd [of two thousand], two encores and a long psychedelic jam.” The band then attended an after party at El Clubbo.

At the foot of the North Island, The Cure satisfied a fierce demand at Wellington Town Hall with two nights and four shows after which they famously linked up with local post-punk musicians for a late night jam.

The English post-punk band’s music was not only popular listening in New Zealand, their spaced out, effects driven guitar sound had greatly influenced a number of local groups including Wellington’s Beat Rhythm Fashion and Christchurch’s The Newtones and The Terraces.

There were no New Zealand support bands that tour. Carnage Visors, a short film by Simon Gallup’s brother with a group composed and mostly instrumental soundtrack, sufficed.

Trevor Reekie noted the band’s set list as ‘The Holy Hour’, ‘In Your House’, ‘The Drowning Man’, ‘10.15 Saturday Night’, ‘Accuracy’, ‘The Funeral Party’, ‘M’, ‘Primary’, ‘Other Voices’, ‘All Cats Are Grey’, ‘At Night’, ‘Three Imaginary Boys’, ‘Fire In Cairo’, ‘Play For Today’, ‘Splintered In Her Head’, ‘A Forest’ and ‘Faith’.

Two shows in Christchurch finished off the successful visit then it was on to Australia, Canada, France and the UK.

Chris Parry managed The Cure until 1988 and Fiction Records released their music until 2000 when Parry sold the label to Universal Records. Throughout, Robert Smith’s gothic popsters would be chart favourites in New Zealand.

The next time Chris Parry made the newspapers here, he was pushing a new London radio station called Xfm. He became involved with the temporary station in 1991 when it broadcast at Reading Rock Festival. Competing for a permanent place in the tight and prized London radio market, Xfm struggled for seven years with short-term restricted service licences, but succeeded in gaining a loyal and vocal audience.

Parry outlined the reasons for his shift in focus to Desmond Sampson in NZ Herald (28 August 1998). “I’ve always been entrepreneurial. I’ve never been comfortable with this sound-a-like look-a-like bollocks. I like to cut my own path and I’m always looking for a fresh challenge,” said Parry. “My taste is left field. I like stuff that pushes musical boundaries and I was bored with commercial radio.”

“Xfm,” he added, was like a “mix between bFM and early Radio Hauraki.”

With grunge exploding and then Britpop, there was a gap in the market for a new style of radio station highlighting more left field, guitar based sounds. Xfm broadcast out of Parry’s offices and staged outdoor concerts and put together compilation albums all in support of the new idea.

On 16 January 1997, Xfm was finally awarded the final London FM licence. Within a year managing director Chris Parry and the station’s shareholders sold the radio frequency to Capital Radio, who closed it down for four days and relaunched as a soft rock station. The outrage was deafening. When the new format failed, Xfm’s new owners were forced to return the station’s musical emphasis to one resembling the original.

Record man that he is, Chris Parry had fired up Fiction Records again in the late 1980s and early 1990s, signing Candyland, Eat, Die Warzau and The God Machine. On the label’s sale to Universal in 2001, Fiction Records began a new life in the mid 2000s with new groups that included the popular Snow Patrol, Ian Brown, Kaiser Chiefs, White Lies, Yeah Yeah Yeahs, The Bees, The Maccabees and New Zealand’s The Naked and Famous.

There was unfinished business with The Fourmyula as well. In March 2010, a box set collected much of the group’s catalogue and included for the first time the unreleased LP, Turn Your Back On the Wind.

“One of the good things about having this box set out,” Chris Parry told NZ Herald’s Scott Kara, “is that it helps put us in the right place in the pantheon of New Zealand artists, because I think it is a bit skewed because of ‘Nature’.”

Live shows in Auckland and Upper Hutt followed with Chris Parry back behind the drums. The former beat keeper with a keen ear for new talent continues to spend a good part of the year at his beach house in Whangamata and the rest in London.

HMV

Polydor

Fiction

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air