The rebel long hair culture that galvanised around Chants R&B in Christchurch and further south around The Unknown Blues was one of the most distinctive NZ youth subcultures to emerge in the 1960s. It was a young, largely male culture which followed swinging London fashion and R&B music with a passion, provoked thoughtful articles about the influence of long hair on young people and just as many column inches in the court news. In 1966, two long hairs, John Dalton and Paul Fisher, were interviewed by The Press about their lifestyle. They were found and interviewed again in November 1994.

When Paul Fisher returned from Auckland the previous year, his hair was already long and his feet clad in a pair of Cuban heel boots. Down at his old haunt, the King Bee Koffee Kellar, a basement club in Hereford Lane now renamed the Stage Door, he found he wasn’t alone. The club was popular, mostly because of its resident group Chants R&B – a sharp act who ensured the pulse beat matched the dark subterranean feel of the cellar club.

John Dalton - Jeff Smith collection

Fisher eventually rented the flat downstairs from Chants guitarist Jim Tomlin and gradually immersed himself in the mod world, which centred around the Stage Door, making new friends among the club long hairs.

John Dalton, Frank Doig, and their mates, Gordon "Noddy" Hutchison, Chris Smith, and John Dunphy, had themselves not long returned from Auckland to find the Stage Door club alive and firing. They soon met up with Paul Fisher and became a tight bunch. Membership was exclusive to those who lived the hard long-hair lifestyle, drinking excessively (drug use wasn't widespread), hanging out at the Stage Door, which became their home away from home, partying long and hard, raving over the new R&B sounds and styles out of England, and getting into trouble with the law.

Paul Fisher in the centre - Jeff Smith collection

Some were no stranger to borstal, particularly the young offenders institution at Waikeria in the North Island. Another long hair trademark was the drunken car safari, where the gang would take off to the beaches east of the city, or down the island to party with fellow long hairs in Dunedin and Invercargill.

Dave Hogan, vocalist with Invercargill's Unknown Blues, remembers them: "Slade, Fisher and friends would visit Invercargill – and call it going on safari – with a boot full of beer in hopelessly overloaded cars.”

As a soundtrack to a wild nocturnal urban lifestyle of the long hairs, R&B was perfect.

"There was a Dunedin, Christchurch, and Timaru long hair connection. We heard there was a bunch of long hairs in Christchurch, and that they were at the Stage Door. A few of us went up on a pilgrimage to have a look, and it was great. I made friends who have lasted to this day like Paul Fisher, Herman Grenall, Tony Slade, and Trev Courtney."

It wasn't all teenage hijinks and drunken car chases. Music remained central to the culture. Like other fans the Christchurch long hairs were forming bands – The Imbeciles from 1964 and Fisher's practice outfit, The Primitive Dynasty – and avidly importing R&B records reviewed in the English music weekly, Record Mirror, from Papworths in Nottingham, England.

John Dalton was the local secretary of The Downliners Sect fan club. Fisher liked the aggressive sounds of the R&B bands, taking in The Layabouts and The Underdogs when they came to town, as well as the obligatory Pretty Things tour in 1965. As a soundtrack to a wild nocturnal urban lifestyle of the long hairs, R&B was perfect. It was snotty, aggressive, full of the hyper-energy many of its followers exhibited, and overwhelmingly male.

For a time, the long hairs worked together in a rubber factory, one of the few places their hair length wasn't a problem with employers, and often flatted together around the city.

Mainstream Christchurch looked on bemused, and David Brunton in The Press, Christchurch's conservative morning daily, attempted to get to grips with the new cult and the relevance of long hair, its principal badge. "It is part of a protest by young people against the world they have inherited – a striving to assert individuality in a society which they see as having carefully-ordered surface values and hopelessly confused inner attitudes,” he ventured.

John Dalton and Paul Fisher - Jeff Smith collection

Prison psychologist H.E. Cohen ventured the cause of male unease with the flamboyant cult. "General insecurity is widespread in New Zealand. Only a man unsure of his own masculinity would be disturbed by this long hair."

Out on the streets, long hairs had to tolerate constant abuse, threats of violence, and ostracism personally and professionally. In the same article, long hair Paul Fisher’s story touches on the reality. "Paul, aged 18, a rubber moulder, lives with his grandparents because his parents refuse have anything to do with him because of his hair. His grandparents tolerate it although they do not like it."

Fisher: "I prefer to retain my individuality. It has become a real principle with me. What amazes the most is how much hatred people can work up towards us when they don't even know us ... "

The long hairs’ most bitter enemies were the city’s rival youth cults, surfers, and in particular, the city's rockers and embryonic bikie gangs.

The long hairs’ most bitter enemies were the city’s rival youth cults, surfers, and in particular, the city's rockers and embryonic bikie gangs. Rockers with their Spartan clothes and short haircuts shared many of their senior's disdain and knee-jerk reactions to the new cult.

Up until then, however, they'd only been the normal tension between the city's teen cults – petty bickering over women, verbal and physical abuse, and general teenage strutting and preening. In late December 1966 – the tragic culmination of a series of running confrontations that month – would change all that.

John Dalton remembers the chain of events leading up to the December 1966 killing of a young biker and rocker called Les Thomas. "Two weeks previous we’d given a party at our rental place in Rutherford Street. The Papanui boys arrived. We would not let them in so they tried to break in. There were about 30 of them. Some had knives. After half an hour they left saying they'd be back next weekend to finish the job. They left behind five broken windows and a shattered door.

"Next week we invited the Sullivan Ave boys around. A close friend, John Byrne, had cousins in the gang. We thought having them with us would either scare off the Papanui gang or help us in a confrontation with them – wrong – they didn't arrive so the Sullivan Ave guys roughed us up – just for a laugh.”

The Papanui Boys returned to Rutherford St a few days later, where they clashed with some long hairs, members on both sides were bottled, but one hard rocker in particular swore revenge on one of the long hairs.

The next week, the rockers turned up en masse at the Halswell Rd residence of long hairs' Phil Turnock, Tony Slade, and Bill Gilchrist. In the following altercation, Les Thomas was shot and killed by Gilchrist. He was eventually acquitted, claiming he acted in self-defence.

John Dalton - Jeff Smith collection

At the farewell party for Chants R&B – who were leaving for Australia – the long hairs partied long and hard, razing Chants R&B singer Mike Rudd's former rental house in the process, which resulted in Paul Fisher and others being arrested. It all made good newspaper copy, and the media, interest already piqued by the killing, was quick to move in.

A sensationalistic Sunday Times investigation into the mods and rocker elements of Christchurch, published on April 30, 1967, nonetheless gave some accurate insights into the long-hair ethos. "Mods drink to get drunk, they are drifters, moving from job to job, from flat to flat. Their most bitter enemies are the Brighton Boys and the Papanui Boys. As a rule mods don't go looking for trouble."

Brian Edwards, a well-known television presenter, went one further and filmed a show about the (mods) long hairs and rockers. Fisher: "He interviewed us at our house. We only let them in when they agreed to buy us a lot of piss, so they did ... They took the rockers to a milk bar, and gave them a milk shake, that was a big bloody joke to us."

Away from the media spotlight, the tension between the two sub-cultures festered on. Jeff Rowe was a young Christchurch mod and Stage Door regular: "The mods vs rockers situation certainly added spice to attending the Stage Door even prior to the shooting. Often you couldn't leave because the boys on their bikes were waiting at both ends of the alley for stray mods to venture out. Usually in those circumstances a quick call to the cops was enough for a constable to be dispatched to move them along. This didn't always work and members of the band, in particular, were beaten up.

"The tensions heightened after the shooting and I was involved in an incident which was the scariest of my life. It took place in Cathedral Square in broad daylight. It wouldn't have been much after 5pm. A friend and I were going down to the men's toilet when we were surrounded by a group of leather-jacketed bikers who told us they were going to do us over because we were mods.”

Dave Hogan fron The Unknown Blues with Trevor Courtney from Chants R&B

"We started talking as fast as we could, pointing out that there were far too many cops around to start a rumble. A couple of cops came over. It turned out they had instructions to disperse gangs of more than three people, but we told them we were talking to our mates and there was no problem. The cops insisted we take the opportunity to make our escape.”

Mike Rudd, Chants guitarist, in the July 1966 Press article, comments on the police attitude: "It depends on the individual. Like the rest of society there are some who are really biased, but there are also some who are very open-minded. For the most part they treat us fairly."

Style-wise they were following the John Mayall bohemian blues uniform of extra long hair, dirty appearance, more flared clothing and sandals.

Meanwhile at the Stage Door (soon renamed the Ram Jam), Chants R&B (who'd moved to Melbourne) had been replaced by Ken Wright's Our Generation. It just wasn’t the same. The mod world centred on the venue was a divided kingdom.

Fisher: "The Stage Door lost its feel after a while. There was a lot of scrapping going on down there. I was probably one of the main instigators. We changed. We were up against the bubbleheads, the mods – Small Faces type people – with hair teased up. The long hairs were anti them a lot of the time. We didn't mingle, and didn't go to each other's parties. If we did we'd get kicked out."

Style-wise they were following the John Mayall bohemian blues uniform of extra long hair, dirty appearance, more flared clothing and sandals, which would become more associated in people's minds with the hippie sub-culture.

Fisher: "Everyone was getting a bit dirtier and looking a bit scruffier." Fisher and Frank Doig had a contest to see who could be the dirtiest, which Doig eventually won. Fisher wasn't so lucky, he was banned from the Stage Door for excess filth, until a petition of regulars saw him reinstated a few months later.

In the late sixties, Paul Fisher moved south to Invercargill, working in the freezing works and flatting with Bari Fitzgerald, guitarist with The Unknown Blues. Fisher: "There were plenty of fights down there. The swords (locals) were always wanting to fight you if you had long hair."

In contrast to Christchurch there wasn't the tension with the local bikers. Invercargill was a different scene from Christchurch. Dave Hogan: "Because it was so small – we all went to the same school together – the guys that surfed and rode bikes, moddy sort of guys, we partied and drunk together, and scored chicks together.”

John Dudson, who moved to Dunedin in the mid sixties, remembers the biker and long hair symbiosis and The Unknown Blues’ part in it all: "Along with Chants, The Unknown Blues were at the heart of mid 1960s long hair culture. It is fascinating to note the blurring of subcultures within the long-hair framework. Yes, the clash between mods (long hairs) and rockers (V8 boys and bikers) was real, and no more so than in Christchurch, where the Papanui Boys, the Brighton Boys, and the Flagon wagons were bitter enemies of the mods. Tensions later resurfaced in a violent three way clash at the Brighton Ramp in 1969 between the V8 Boys, surfers, and Epitaph Riders (bikies) with the police struggling to gain control.

Go further south and you would find The Unknown Blues in V8s. Bari Fitzgerald, a dedicated musician and avid record importer, prided himself on having the longest hair in the South Island and was as dedicated to 1939 deluxe Fords as to his music.

"The Unknown Blues knocked around with The Antarctic Angels. Bari's sister went out with Davey Johnstone of Christchurch, who could challenge Bari for length of hair, and was the founder of the Epitaph Riders MC. The President of the Angels (the late Roy Read) was a follower of The Unknown Blues, and judging from photos Bari still has, dressed more in the long-hair and mod style of the time than that of any prototype English biker."

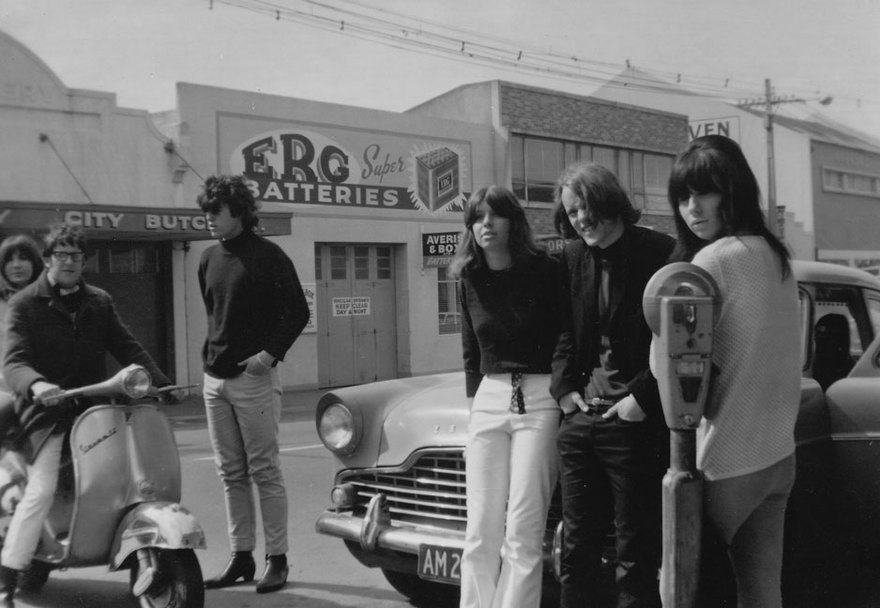

Mods. - Jeff Smith collection

As the 1970s loomed the long hairs drifted apart. Some returned to Christchurch, and became involved in the city's biker culture, most of The Unknown Blues moved to Australia, other long hairs drifted in and out of prison, or became dependent on drugs. Some, including John Dalton, settled down.

Paul Fisher wasn't so predictable. Back in Christchurch he was developing a taste for head music and LSD. He moved to Temuka near Timaru in the early 1970s where he became a successful and admired potter, studying for a while in Japan. While in Temuka, he had a family with Lyn, whom he met at the Stage Door.

When punk rock arrived Fisher recognised the vibe and formed Catholic Taste, then FN99, a name copped from a loose description of Christchurch bikers (Fucking Near 100). Fisher's abrasive personality finally found an appropriate musical release. FN99 played a set of Fisher faves, including ‘Get The Picture’, ‘Ugly Child’, ‘Roadrunner’ and ‘Cops and Robbers’. Other bands followed, including Tex Amplifier, a rockabilly style band.

He remains a Pretty Things fan to this day.