The following interview with Flying Nun founder Roger Shepherd, conducted by John Russell first appeared in RipItUp magazine in July 1997, shortly after Roger had left the label in the UK.

–

When Roger Shepherd started Flying Nun Records in 1981, he was considered something of a maverick. Here was a young record store manager, not content to roll over and sell the big names from overseas, but more concerned with promoting the cause of a handful of unknown South Island bands and their collection of uniquely New Zealand pop songs. Shepherd displayed entrepreneurial flare from the very beginning, recording and releasing The Clean’s now legendary first single ‘Tally Ho’ for only $50. Soon after, that band’s debut EP, Boodle Boodle Boodle, reached Top Five in the local sales charts, kick starting Flying Nun’s love affair with New Zealand music enthusiasts at home and abroad.

With Flying Nun, Shepherd not only brought to the attention of the public great bands that might never have made it beyond the garage, he ensured they were given a climate to thrive in. Prior to the emergence of New Zealand’s first substantial indie label, few local bands ever recorded a second album. Flying Nun fostered the careers of groups such as The Chills, The Bats, The Straitjacket Fits, and The 3Ds, who all went on to receive international acclaim, after releasing two or more albums each in New Zealand.

More than any other local label, Flying Nun has drawn worldwide attention to New Zealand music and musicians, a fact recognised by Rolling Stone in 1989, when they included Flying Nun in their roll call of the world’s top independent labels.

Three years ago, Shepherd moved to London, to continue to promote Flying Nun in the international market. After overseeing Garageland’s introduction to the Northern Hemisphere, Shepherd resigned his position at Flying Nun in March this year, in order to pursue a new lifestyle. RipItUp caught up with Shepherd at his home in Shepherd’s Bush, on the outskirts of London, a few hours before he left for a two-week holiday in France.

Having been away from the label for a few months, have you done much reflecting?

“No, not really. Obviously I very much miss my involvement with the bands, and being involved with everyone in the New Zealand office, but I think the break from it has been good for me. I’m still at that stage where I’m more thinking about what I’m going to do, and I haven’t got any firm ideas in that area. I guess when I do, I’ll be a bit more able to look back and have a good view of it all."

Roger Shepherd 1994 - Photo by Jane Alexander

Did you get out of the business with your enthusiasm intact?

“I think so, because I feel as though l’m going to do something else in music, and it’s been a pleasure to be thinking about doing something new. If anything, I feel as though I can get back to being genuinely enthusiastic about music again. I’m probably listening to a lot more music on a personal level than I was three months ago, which is good for me.”

When a music fan starts a record label, as you did, is it inevitable the business side of things will take over the more fun aspects of the job?

“It's not inevitable, it depends on how it grows and how it ends up being structured. Some people do really enjoy all that business stuff, I didn’t mind doing it, but it got to the point in the end where I didn’t enjoy it enough to warrant carrying on.”

Was it a battle to not get cynical about the music industry?

“It’s very easy to be cynical about it, but the bigger worry is being cynical about the actual music, and certainly [in the UK] there's a lot to be cynical about. It’s very commercially driven here, very chart orientated, and for someone like myself, who’s been doing something in the music business in some shape or form since 1976, everything seems to have come around at least a couple of times. I go and see a lot of bands, and listen to a lot of records that are hyped here, and I feel quite often that I’ve heard it all before. But I still get a kick out of seeing a band that really surprises me, and that’s probably going to propel me back into starting another label.”

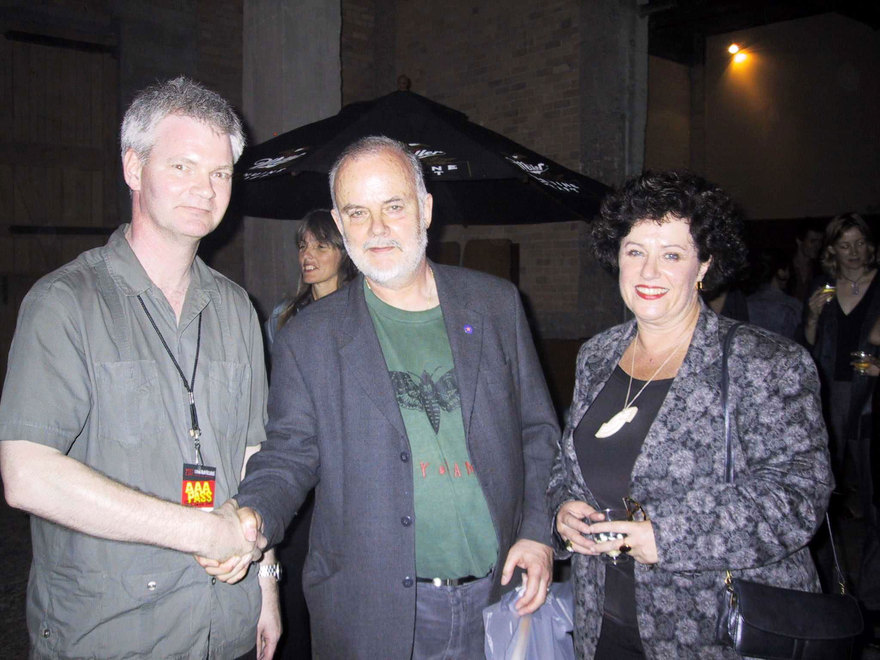

Roger Shepherd with John Peel and Judith Tizard at the Flying Nun 21st Anniversary party, 2002

What do you consider the pinnacle of your achievements at Flying Nun?

“I suppose I see it in quite mundane terms of just being able to help make a lot of that music available. It was a pleasure for me to be involved with those bands and to be able to help in some way. Obviously on a musical level, certain records mean a lot to me; all the Tall Dwarfs stuff, early Clean stuff, and a bit later on The Chills and the Headless Chickens. There's a whole heap of records that stand up as being pretty good that came out of it — I'm happy.”

Roger Shepherd with an upside down gold disc for The Headless Chickens' Body Blow album

How do you think It happened that all those key people were in Dunedin at the same time, and involved in that creative burst of the early 80s?

“That whole post-punk thing happened everywhere really. After punk hit, a lot of people realised they could make music, and it was possible to do it in a cheap, affordable way. There were interesting things happening in Auckland and Christchurch, but I guess the focus was on Dunedin, and those people were in that place listening to their record collections, talking to each other about music, forming bands and writing songs, and it just grew. I really don’t know what the reason is, probably just chance.”

Do you feel there’s still a perception Flying Nun has a uniform sound, either at home or overseas?

“That has always been something that people would say in New Zealand, it’s not something anyone has ever mentioned to me anywhere else in the world. People’s perceptions of the label don’t worry me at all, people react to individual records and that’s what matters.”

Ever get tired of sheep remarks in every overseas review of a Nun band?

“You wonder why people are obsessed about New Zealand and sheep, and it’s because it’s quite a strange thing that there are 60 million sheep and three million people, that’s a hard thing to get your head around. If you’re away from New Zealand for a couple of years, you find it increasingly odd.”

According to Flying Nun New Zealand’s General Manager, Lesley Paris, in 1990, the Australian label Mushroom Records bought a 50% stake in Flying Nun. Three years on, they purchased a further 25%, and in March this year, when Shepherd left Flying Nun, Mushroom acquired the remainder of the company.

When Mushroom first became involved with Flying Nun, did they muscle in and take any of your control away?

“Not at all, it just meant that we had a few more resources, and the bands that had ambitions about doing well internationally, we were able to find the funds to record their records and stay involved with those bands — the Straitjacket Fits, JPSE, The Bats.”

With the increased financial resources, did you feel that recording budgets for the Fits (Blow), JPS (Bleeding Star), and The Bats (Sllverbeet) got out of hand in the 1992/93 period.

"There were probably a few projects where the budgets did get a bit overblown, but it all calmed down quite quickly. We’re still not talking about huge amounts of money, we're talking about budgets that were quite a bit bigger than what some of those bands were used to, but not that expensive when you look at what people spend in Australia or spend [in the UK]. Part of the problem with bigger studios and name producers is that everyone – whether it’s the label or the band — is a bit inexperienced and it ends up costing a bit more.”

In the 1993/94 period, when the Fits and JPSE split, and several other bands took extended breaks, did you feel the label was in a bit of a rut?

“I remember being conscious of the fact a lot of the more established bands were disappearing, but I don’t remember it being a major problem. To be quite honest, I can’t remember that period very vividly.”

In 1993, Mushroom opened an office in London to spearhead the Australian label’s attempts to sell their acts beyond Australasia. Mushroom had previously enjoyed some success in the UK in the late 803 with Kylie Minogue, but the label’s success had waned by the turn of the decade. With the New Zealand wing of Flying Nun having already established a good reputation in the UK and Europe, Shepherd shifted to London mid-1994, to set up Flying Nun UK, which operates from Mushroom’s London headquarters.

When you shifted to the UK, in what ways did your perspective on selling Flying Nun music change?

“It’s just a bigger place with a bigger music industry, and it takes a lot more to get your message across, to get people aware of a band or a record. If you’re really going to try and do something properly in a commercial sense you have to spend money. Basically, you do all the things you do in New Zealand, but the scale is a lot bigger.”

What do you see as the biggest problem for New Zealand bands making the move outside their home market?

“It’s just the problem of starting again really, I do think if the band wants to be big in America, the band has to live there, or if they want to have a go at doing well in Europe they have to live here. It’s so competitive and so commercially driven, and if you’re keen to have a career and make some money, you’ve got to play by the rules. If you move from New Zealand and you’re living [in England], you need some money to live on, and unless you’re going to have day jobs, you need to play some of the games to get ahead here in the industry.”

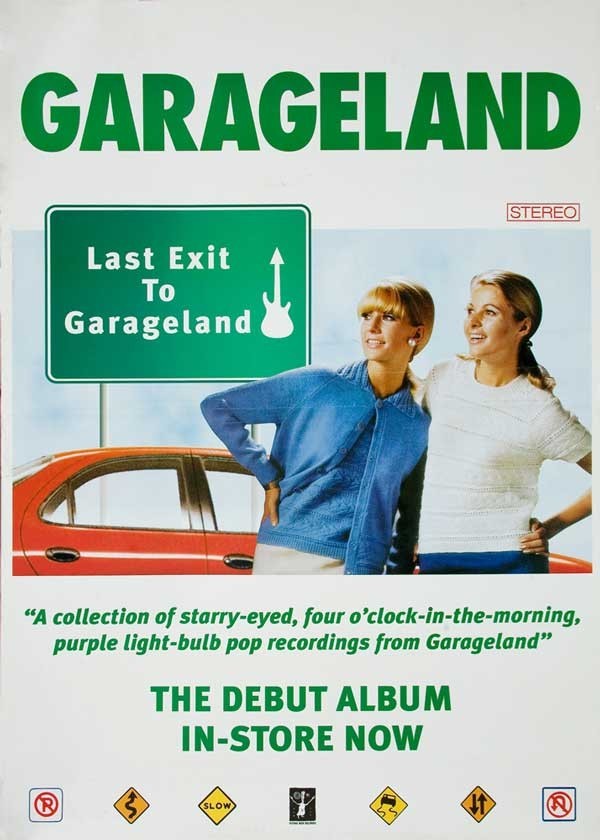

Garageland were a major 1990s UK priority for Flying Nun

What needs to happen in the UK, for Garageland to have some impact?

“They’re getting close to the point where they really need some radio play, but that's something that doesn’t just happen. I’d say the crucial stuff that’s going on at the moment is getting interest at radio, so when the single that radio is going to like and everything is right for them to play it, there won’t be any excuses for them not to play it.”

In terms of the European market, is It a better time for Garageland to be there, having a crack, than when The Chills were there in the mid-80s?

“The Chills came so close to being a really happening thing here, they were right on the edge of being a big band, it was just unfortunate that when they came back to New Zealand, the band broke up. It's still early days for Garageland, they’ve been here four months and they've played about 55 gigs in that time, and they’re just starting to get noticed. They’re at a point now where they’ve been around for long enough that people identify them as being a band based in London, which means they're almost British, which means they’re almost ‘OK’, so they can be taken seriously. It’ll be interesting to see what happens over the next nine months. It’s quite weird to be talking about it, because l no longer have any involvement in it, I’m only an observer now.”

Also housed in Mushroom ’s London office, alongside Flying Nun UK, is the Infectious label, which is home to the Irish trio Ash. Infectious Records is run by Korda Marshall, who in January this year also became the head of Mushroom’s British operation. Two months later, Shepherd resigned, stating he could no longer tolerate dealing with the business side of running a label; “I wasn't finding that it had anything to do with music anymore.”

Did you leave Flying Nun UK 100% willingly?

“Yes, indeed.”

There were rumours that Infectious were Interfering In the selling of Garageland, and that you weren’t happy with that.

“No, there hasn’t been any problems like that. The Garageland thing is running really well, the guy that’s looking after them is very competent.”

What are your Immediate plans?

“There’s quite a few options, I haven't really got to the point of making up my mind, but no matter what I do I’ll probably start another label, and just do it on a much smaller scale.”

Will you return to New Zealand to live at some point?

“I'll come back at some stage, but at the moment, I don’t really know what there is for me to do. I don’t know what sort of job there would be for me in New Zealand if I wanted to do music. For now, I’m going to stay here and enjoy this part of the world, and see if I can get something else going.”

--

© 1997 RipItUp, reprinted with permission.

--

In 2018, Roger Shepherd was named Officer of the New Zealand Order of Merit for services to the music industry.